Stored

The series produces an eerie prediction for what's to come. "A day in summer 2020. Social isolation has become normal. The new disease is called hypochondria," says Roché.

Check out the rest of the series below.

Stay informed on our latest news!

The series produces an eerie prediction for what's to come. "A day in summer 2020. Social isolation has become normal. The new disease is called hypochondria," says Roché.

Check out the rest of the series below.

Born in Canada in 1971 to Chinese immigrants, Mao was brought to Michigan as a baby, where he would live until his departure to New York in the 90s. Art has always been a fixture in Mao's life, motivating his decision to study and earn his BFA at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. The 90s art world was very different than today's, where diasporic voices and artists of color were discounted, either ignored or misunderstood. This culture of exclusivity prompted the then-New York-based artist to acquire skills in foundry work in San Francisco before returning to New York and beginning work at a design-build architecture firm. While simultaneously making art and begging more and more questions, Mao found himself in Mexico City for a residency in 2014 — a city that he now calls home. Mao's life journey has forced him to consider himself in this transnational context, informing much of his work today.

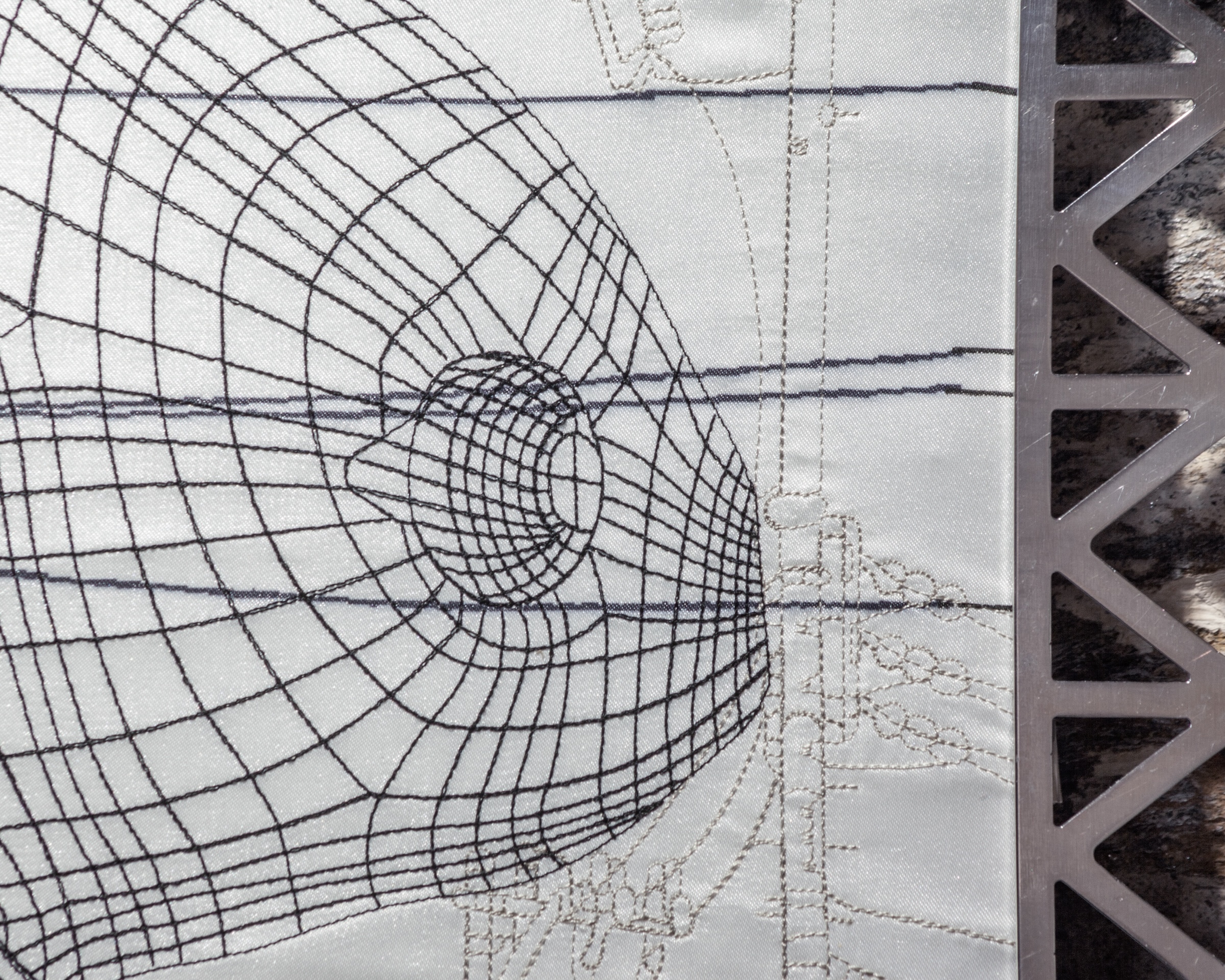

At the beginning of our video chat, Mao mentions how his forthcoming offering at Freize is years in the making. "For the Frieze presentation, I'm basing it on this research that I've been doing for some years now," the contemporary artist explains. "Freemartins" came to be through investigations into Mexicali and its "impenetrable history," a Mexican border town housing the largest Chinese population in the country. In the early twentieth century, coinciding with the Mexican Revolution and exclusionary laws implemented by the United States, the Colorado River Company exploited many Chinese immigrants through work in agriculture and irrigation. The unfamiliar climate and hot summers prompted Chinese workers to build out their basements into a tunnel system, an underground city called "La Chinesca." As the years passed and anti-immigrant sentiment began to spread in Mexico, La Chinesca became a refuge for the city's Chinese population. "Now the tunnel system is only reduced to just these few basements," Mao explains. "I have measurements of these basements. So I use the floor plans of them, and they're cut out of steel plate, and then using that as a basis of the sculptures."

Establishing an underlying — usually nonlinear — narrative is a common thread throughout Mao's practice. After pulling directly from these artifactual spaces, illuminating ideas of liminality, and addressing opaque histories and experiences of diasporic identities, the Mexico City-based artist's approach to this project has provided a basis for much larger ideas. "These floor plans are sort of loosely assembled, so they look like they are coming apart and coming together at the same time. I can use that as the basis for other things, in my practice," Mao states. "Thinking about this orality and the body and architectural space, the dissolution of bodies, and our relationship to myth. This idea that I've been playing with a lot lately of us being related to mythical creatures and sort of relating that to this idea of animism. These animals urge an intelligence of the body — beyond the spiritual mind. All that is sort of inside of these sculptures."

This richness of depth and embedded intentions is apparent not only in the work as a whole, but also in the details and the materials themselves. "[The material] is about this threshold or boundary, decomposition, and composition. I'm thinking about them as material that is moving through time in some way that is breaking apart," the acute artist mentions. "Steel is one of my main materials. Steel is made out of a few elements that have been industrialized into a thing, and then, it's possible that it can rust and disintegrate and go back to the earth." This notion of transience remains a pillar in Mao's practice and an essential facet of "Freemartins," engaging in ideas of fragmented histories, considerations of one's position in nature and the industrial complex, and relationship with time. Fig 39.7 Bardo, the steel armature confines the lava rock, pierces steel bars through the natural material, where a silent dialogue of ephemerality is being had.

fig 39.1 freemartin, 2024

fig 39.7 bardo, 2024

Although Mao's work is laced with conceivable qualities of anthropomorphism and narrative, the work traverses realms of abstraction where discoveries offer more questions than answers. "I really believe in abstraction. And I think that abstraction is hard to talk about. It's hard to write about, but there is this sort of liberation that's happening with abstraction where I can make a figurative sculpture that's not a figure. And it can, therefore, be open enough to talk about all these other things that are happening in the world that may not be as easy to define," Mao states after taking a drag from his cigarette.

Mao's departure in 2015 from the U.S. has allowed for uninhibited artistic freedom — igniting an inner part of himself. "I'm trying to embrace this structure of poetry and this sort of weirdness and abstractness," the esoteric artist states. Since calling CDMX home, Mao has produced incredible work featured in "An array of disruptions and codependencies," in London, "I Desire the strength of nine tigers" in New York, and "Yerba Mala" in Mexico City. Some of his recent work has delved into personal history and ancestral knowledge — a new exploration for the artist. These projects centered on "My mom, dad, and my grandfather, and all this stuff that I had sort of been ignoring, or maybe felt wasn't valid or worth going into," Mao explains. Now, with "Freemartins," an attempt to slowly make his way back into the United States art scene, Mao's subject matter of race, sex, transience, and issues of fragmentation appears as the right entry point to do so. "It feels like it's this sort of, not full circle, maybe a half circle moment," the 52-year-old artist notes.

As our call nears the end, I ask Mao where he sees his art in the future. He states, "I want to push the work. I want to embrace the abstraction in the work. It's an impulse for me to rely on aestheticism. And I think that the type of work when you walk into a gallery, and you say, 'What the fuck is that on the floor?' and 'Why is this in a gallery?' That's the kind of abstraction that blows your mind. Like, 'What is this object?' and 'What does it mean to us? Why is it even here? How did it come to exist?'" There's a slight pause, "I want this stuff to get weirder and weirder."

Ultimately, Davis settled on “Secrets to Graceful Living,” unanimously agreed upon by featured artists Anna Pederson and Radimir Koch. On view at ARTXNYC through February 25th, “Secrets to Graceful Living” highlights two artists who, at first glance, work in wildly different mediums. Koch’s contributions are large-scale resin sculptures, digitally sculpted using ZBrush and borne into the physical realm through 3D printing. Pederson, meanwhile, produces small beaded tapestries, meticulously woven using bead looms.

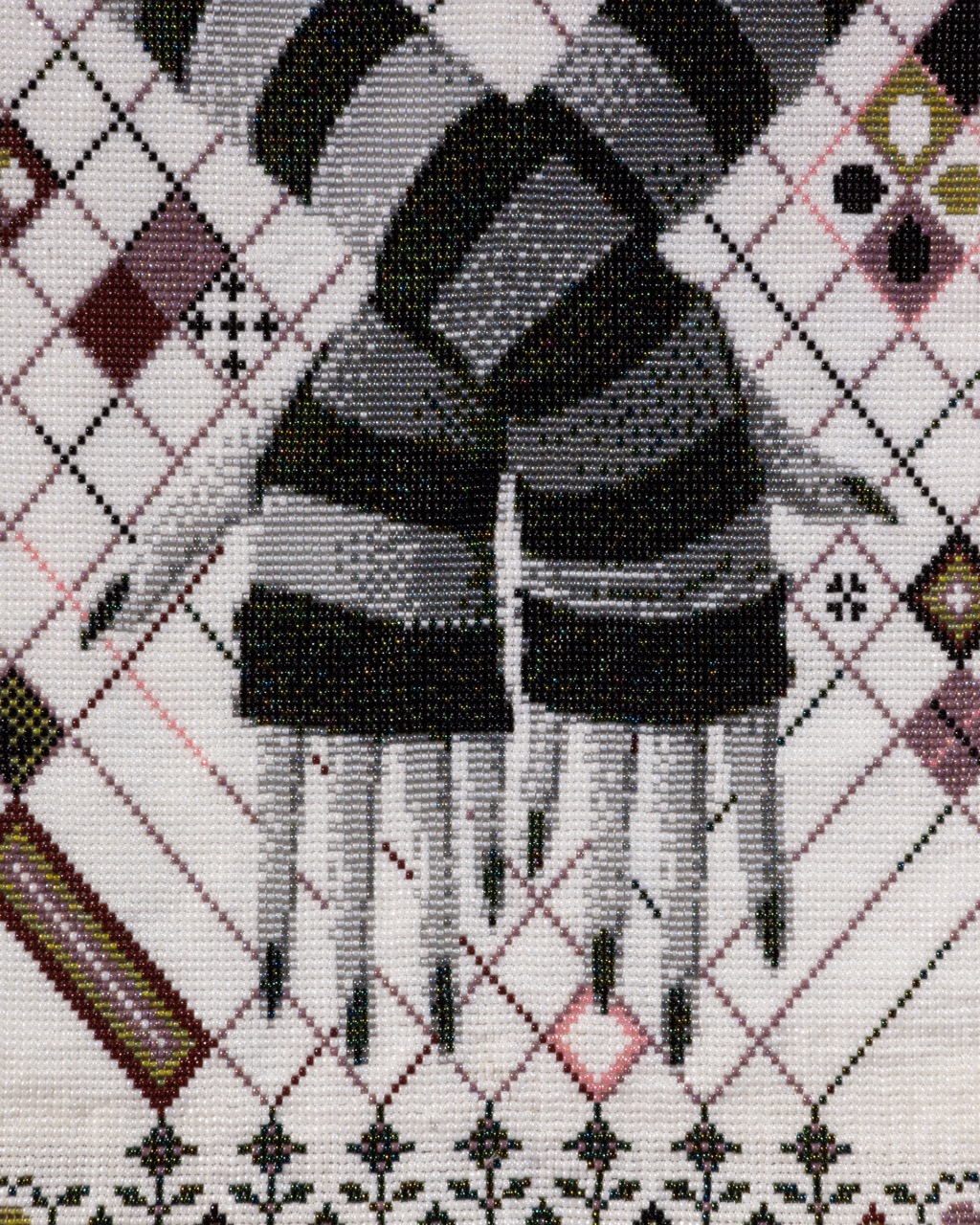

In spite of their superficial differences, both artist collections are informed by digital design. Much of Pederson’s imagery is sourced from the internet, whether it’s stock photos of pylons (see Sentries) or Chibi-style avatars via Gaia Online (see Blessed Avi). Bead by bead, pixel by pixel, Pederson transforms digital images into tangible tapestries. What emerges is uniquely uncanny, an illusion of pixelated perception beyond the screen. “A lot of my work happens on the computer, but I need things to be physical,” Pederson explains. “I could never purely be on the computer.”

Like Pederson, Koch enjoys the process of realizing digital art in physical space, arguably a form of alchemical transmutation in itself. “I want people to experience more than just a flicker,” he tells me. “I want to feel like an avatar in my own little world.” Initially, this desire was largely driven by feelings of anxiety and isolation. Born and raised in Kazakhstan, Koch moved to Colorado with his mother when he was eight years old. “Instead of growing into it, it was like a straight brick wall of America to the face,” he laughs. “Walmarts, Sonic drive-through and all this shit. I was like, what is happening?!”

Alienated by the onslaught of Americana, Koch sought refuge in a circle of imaginary friends, sketched into reality in a series of comic books. Inspired by gory 90’s video games like Serious Sam and Grand Theft Auto, Koch upped the ante in middle school, using game engines like RPG Maker to build and modify worlds in the virtual realm. 3D printing, Koch feels, is his way of “bringing it all together,” reanimating digital design in three-dimensional space.

Although his work is the product of man and machine, each one of Koch’s pieces is imbued with organic features. “People usually think of highly advanced 3D-rendering technology as being divorced from the warmth and gentleness of domestic arts and crafts,” his artist notes read. “In these pieces, there is an aura of a growing garden.” This unlikely union is honored in the exhibition text, written by Mitch Anzuoni of Inpatient Press: “There’s a great bloom of machinery and moss...meshing together…” Indeed, this “meshing together” can be seen in works like Eternal Pond 002, which features a bed of tufted moss encased in cold, curving ceramic reminiscent of Marcel Duchamp’s legendary Fountain.

In other pieces, Koch’s tribute to organic design is more subtle. The insectile symmetry of Mekhana 001-003 is simultaneously familiar and alien, seemingly poised to copulate with a strange series of circuits. Mekhana 002 appears again on Exo Relic 002, profiled in textured resin that resembles an aging headstone. In this way, Koch reconciles discord between categorically antagonistic entities: nature and technology, softness and severity, the familiar and the foreign.

Pederson, too, confronts duality in her work. Like Koch’s Floral Relic Pond 001, pieces like Blessed Avi contain oppositional elements of delicacy and danger, inviting yet barbed. In Doomed Avi 1, a feminine avatar gleefully displays an armful of shopping bags amidst a dystopian scene of urban sprawl and earthly decay. In Sentries, a 3D model of a koala is flanked by pylons.

“Industrial imagery has always been a peripheral interest, but for this show I really dug into the Industrial Revolution, researching railroad and agriculture equipment,” says Pederson, who cites American photojournalist Walker Evans and German photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher as visual influences. In a work like Sentries, these industrial elements take on the sort of formidable beauty usually ascribed to geographical features like mountains or waterfalls. “When you assign character and whimsy to things around you, it's a better life,” Pederson tells me, eschewing the prospect of a future characterized by dystopic doom. “Blood-brain barrier aside…a 5G tower kind of looks cool to me.”

Pederson also explores contradictions within the nature of her chosen medium. In pieces like Family Unit and Roxy, she frames internet-inspired imagery with designs that evoke the ancient art of embroidery.

“Secrets to Graceful Living,” in this way, is largely a collection of anachronisms. Both Pederson and Koch toy with the notion of linear time, alternately signaling the past and future in content and form. Koch’s Exo Relic 001 exemplifies this tension. Although it possesses the sheen of futuristic design, it ultimately resembles a cicada, partially chewed away as if in a state of advanced decay. As a symbol, the cicada is fitting, signaling infinite rebirth and resurrection. “A lot of the work is imbued with symbols of afterlife, death, and synchronicity,” Koch states in his artist notes. “It could be post-human, or it could be pre-human.”

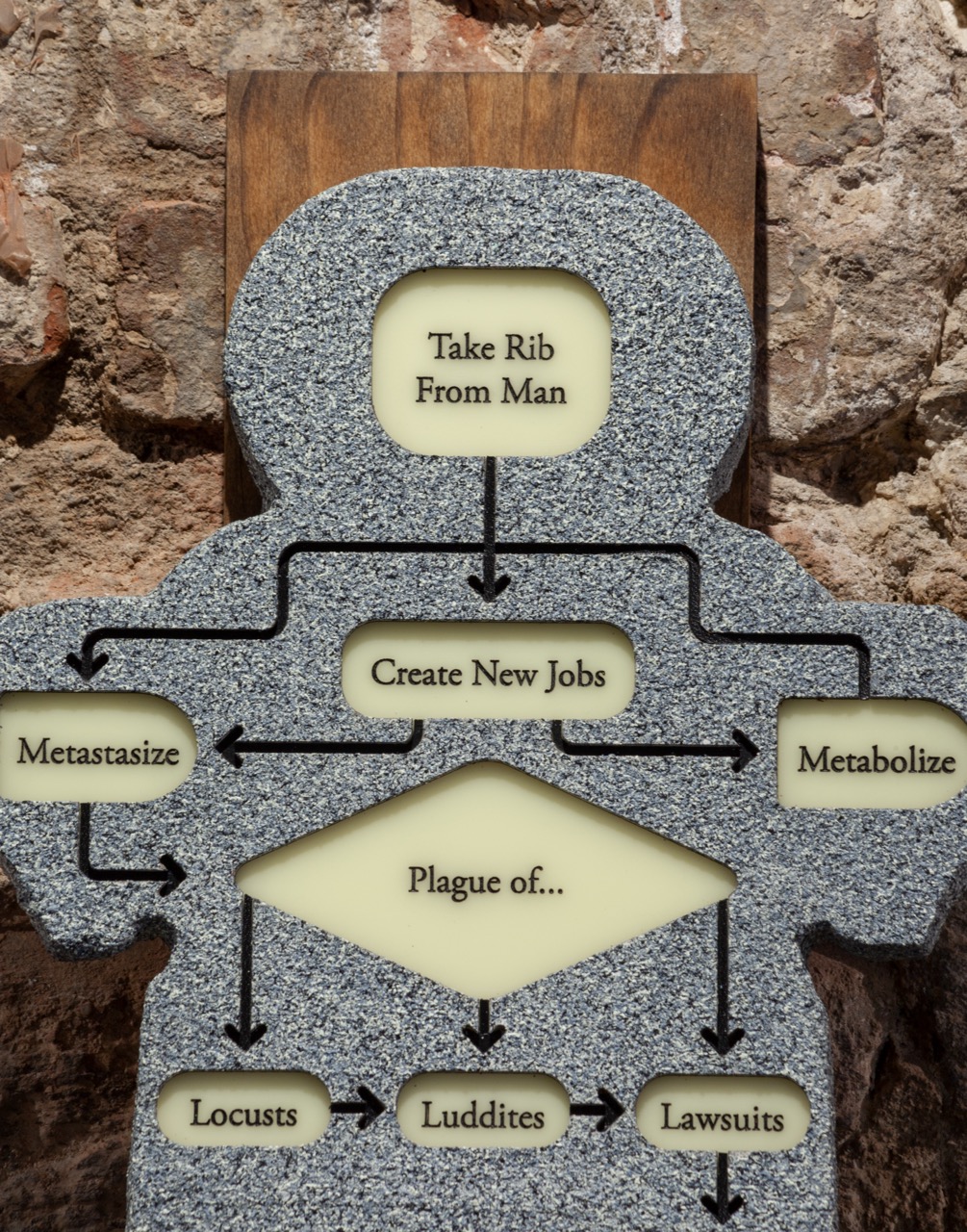

While Koch’s work often alludes to spiritualism and metaphysics, Pederson draws on biblical elements. This influence is most prominent in 200 Lbs of American Born Flesh. Pederson’s human-like tablet (her only bead-free work) displays a sort of existential flow chart, starting with the proposition to “Take Rib From Man” before cycling through plagues of locusts, Luddites, and lawsuits. It’s absurdist humor at its best, featuring hyper-contemporary suggestions like “Review Data Policy” and historic George W. Bush quotes like “Now Watch This Drive.”

In light of the Dimes Square-driven glamorization of Catholicism, Pederson assures me that her biblical references are not the product of recent fascination. “I grew up Lutheran and went to church every week until I was 15,” she says. “I didn’t think about it much growing up, but I’m now realizing just how many references there are in art and culture that would have gone over my head if I didn’t go to bible study.” Eternally-relevant, such references amplify the show’s pervasive atmosphere of being lost in time.

Evoking the ancient practice of alchemy through echoed themes of timelessness, transmutation, and the union of opposites, “Secrets to Graceful Living” transcends cheap shots at technocapitalism. To claim it’s devoid of messaging isn’t accurate either, however. Alyssa Davis has clearly allied herself with the gray area, an infinitely richer well for the future of art.

“Secrets to Graceful Living” is on view at ARTXNYC through February 25.

Everything No One Ever Wanted, Spichtig’s largest exhibition till date, doesn't grapple with the now; it formalizes it. Perhaps a now that no one ever wanted. A time where radical visual appearances are passé and the mod de jour lies in thematic newness, embraced by those, not necessarily capable, but willing to greet it. Institutionally approached, it acknowledges Baudrillard's ideas about simulacra and simulations, suggesting they may only scratch the surface of post-modernity.

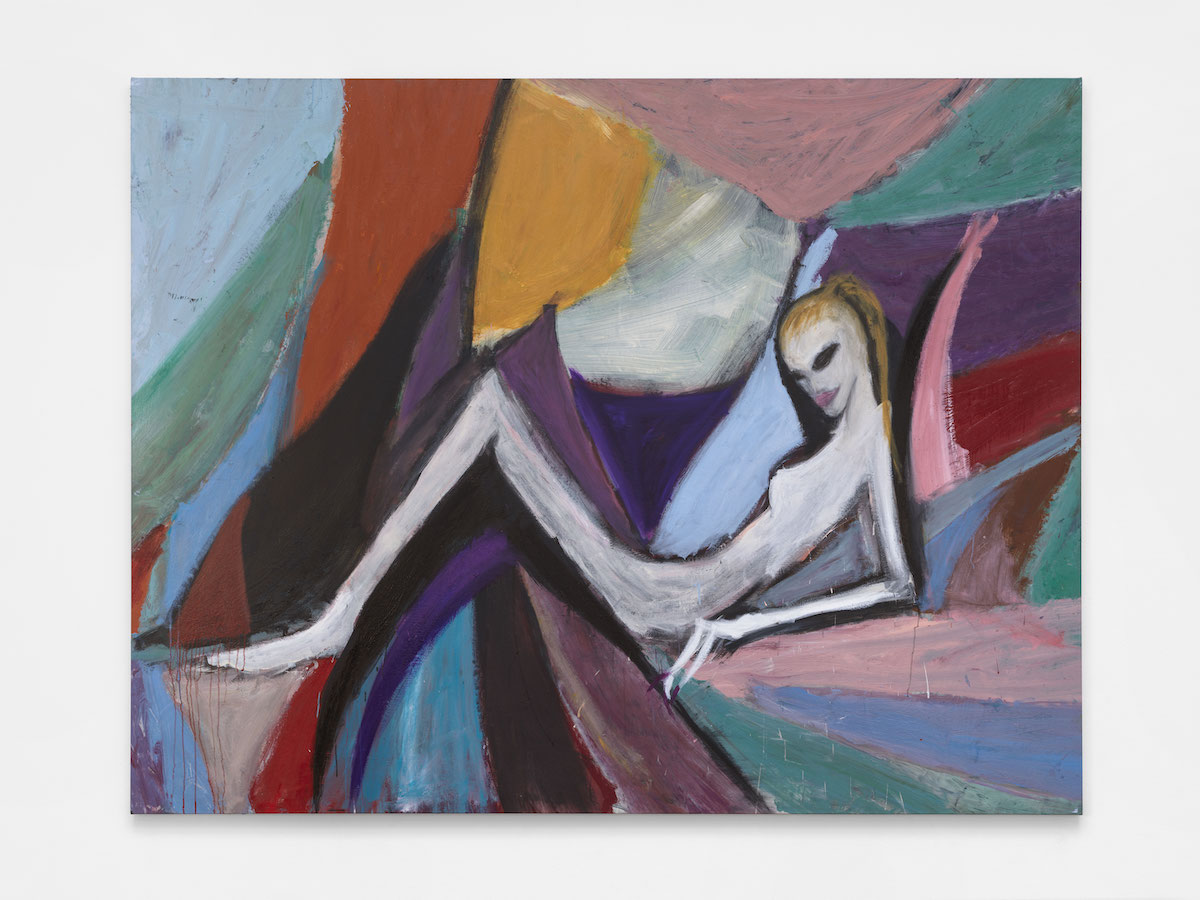

Does this climate also reject appearance? Not entirely, but Spichtig’s pieces aren't purely conceptual either. Instead, they seem to mark a later, perhaps more mature stage of his practice. At Kunsthalle, we witness him taking a step back from the exhausted criticism of capitalism exemplified by his Good Ok Great Fantastic Perfect Grand Thank You (2021) vitrines, which expose our materialistic hedonism with French exit flair, and turning towards painting. His Empty Wardrobes guarded by the vampire-ish portrait of Tom, suggest a constant bloodthirst of consumerism, but his sculptural Geisters or “ghosts” are more convincing. These figures, more than vessels conveying contemporary physical presence while being inwardly absent, nod towards a lack of personality as urgent as today's fashion — where character is swapped for customization and personality for performance. And it suits Steyerl’s poor image just perfectly.

Spichig paints through the screen pulls from Bernard Buffet’s figurative paintings (1928-1999), perhaps his miserabilists. However, while Buffet's portraits such as “Toréador,” “Emile,” “Clown á la trompette,” provide a palette of subjects, Spichtig remains exclusively obsessed with his vampires; his "Geistesgeschichte". Through their natural thirst for blood, they become what humans hunger for — the cultural manifestations of the early 21st century. It's not necessarily that we want them, but that doesn’t deny that we want them to want us. (They're akin to the February stage of this cuffing-season's crush.) As long as we're flesh, bones, and blood, not data, digital, uploaded or cornered all too accurately by our Instagram explorer page, the vampires still want us. It's a testimony against Tesla. Thus, in the company of Spitchig's vampires, the modern man, not the modernist, finds comfort.

Model Sitting, 2023. Hand Holding the Void, 2023

Congratulations on the show, I was told the opening went well.

It was great, my biggest show so far. I got invited by Elena Filipovic, and she’s one of the most important curators of our time, so that in itself was a dream come true. Besides that, I’ve never shown institutionally in Switzerland before, just in The States, Germany, France, etcetera, or smaller New York galleries, which is fun obviously, but this one was different. The space in itself is legendary.

How long had it been in the works for?

Felt like I’ve been working on it for a decade.

That "my-whole-life" feeling?

Almost, but not really. The show isn't a retro perspective, all works are new and, in all honesty, I finished most of them on a tight deadline just before the opening. That being said, a lot of pieces and ideas that I’ve been developing in the past came together and suddenly this brand new composure made so much sense. But to answer your question in a more practical way — I got the invitation in April, so it hasn’t even been a year, which is crazy to me.

Studie für ein Gesicht / Study for a Face, 2023. Titelgeschichte (Geistige Figuration Teil 1) /Cover Story (Geistige Figuration Teil 1), 2023 Stupid Sadness, 2023. Tom, 2023 [infront of] Empty Wardrobes, 2024.

Let’s go back to the opening for a second, I know you brought in Mick Barr to complement the evening through his sound.

I did indeed. He’s a great musician and artist, making drawings too, but mostly known for his metal music. He’s also whom I listened to as I was making the paintings. I usually just put one track or artist on endless repeat, and he was The One. Once I realized that it would be cool to complement the show with a score, it only felt natural to reach out to Mick. I asked him to create a short piece, just a few riffs, but then it ended up lending itself to almost an entire album. The way I see it, It’s no longer just a complementary sound but his own piece in the exhibition. We’ll see what happens with it.

In your interview with Oliver Zahm you mentioned how “a good painting is as if a star would sing live constantly,” were your paintings still singing once Barr closed his set?

My idea of painting is similar to that of music; a feeling or sensation you couldn’t explain with words, but something which you could return to emotionally, that keeps showing up everywhere — putting you back into that sensation–once you're truly touched by it. There are several iconic paintings that show themselves to me everywhere I go, I just love that. It drags you back in.

Are Francis Picabia’s paintings all around your surroundings, then?

[grins]

He has this great quote which, well, I’m paraphrasing now, but “in order to have clean ideas, change them like shirts.” This was once he divorced dada. How often do you change shirts?

Sometimes, not all too often. I like t-shirts and garments in general that are worn until they fall apart.

Then you should see my shoes at this point. I like how subjective “often” is in this context.

I somewhat agree with him [Picabia], though. T-shirts do become dirty after a while, but the way I see it, is that depending on who wears them, they can look better when worn out, or even smell nice if one likes the person who wears it, but then they can also smell bad, and look like shit. I’m not an artist who has a lot of ideas. I tend to stick to what I like, once I’ve been able to find out what that is.

Picabia claimed to do a lot of “different things” but at the end of the day he worked continuously with his abstractions and clear figurations, which aren’t to say these aren't great works — I enjoy them, and they were very impactful for later artists, Warhol and so on, which is why I have an interest in Picabia himself.

For his impact rather than his practice?

More for his insanely beautiful paintings.

What about your own practice, I’m thinking about the various mediums you span — installation, sculpture, painting?

I see myself as a painter because that's how I work on a daily basis, likewise it’s what I truly love doing. My figurative and abstract works run in parallel, or in close proximity to one another, almost always oil on linen, canvas, or wood. Once every now and then I make some sculptures. I’m rather traditional — not an elaborate sculpture, so to speak — nor do I necessarily try to be. The figurative sculptures look a bit like ghosts, very classical in terms of poses, the creasing and details. Much like renaissance marble sculptures but out of clothing and resin. Their name [“Geist,” German] translates to both ghosts and to spirit, I would describe it as a way of thinking, or a specific ethereal presence. They’re a bit like creatures, at the same time they’re not really visible, so while being present, they’re also absent. Which ties them back into the spirit in painting.

What struck me about them is how they feel like advocates for how fashion has moved away from character to custom; everybody can perform anything, while the personality is being compromised, thus they’re empty.

Oh, that’s funny. I quite think the opposite. If it’s even that complex. My idea originally came from depictions of shady figures and the personification of death in paintings that I was exposed to as a kid. They’re very characteristic and almost comical individuals — anything but custom, a main character. But then again, due to their empty/openness, one can imagine things of their own in them.. I like to leave my work very concrete, yet open at the same time, even more so in my paintings.

To me, fashion is constantly over but still always present. It's a weird tension, one that is interesting to me — it somehow always remains, and reinvents; that's a good characteristic. While art, on the other hand, always documents this tension in a less tangible form, thus remains timeless. I’m after iconic images.

I heard that you initially created them out of your friend's old clothes; are they there to remind you of the fact that you’re alone or rather always in company?

Both and neither, think of how children talk to their imaginary friends, gradually they’re becoming more real and absolut, but then suddenly, they’re gone.

… and then everybody assumed they’re crazy for speaking to thin air.

We Could Be Angels for Just One Day, 2023. Me in the Studio, 2023

What about the title, Everything No One Ever Wanted? It feels like a pretty accurate comment on our current — I wouldn't want to say cultural, but general, climate.

I don’t feel concerned about culture, rather I think it should have its natural way of progressing, even if that’s a messy one. The avant-gardes were really messy, but instead of stressing out on visual appearances we named them the avant-gardes, it's possible that that took away from what they were creating. Speaking personally, I’m fed by disorder, and fine with the fact that I can’t do or see everything all at once. The exhibition is a response to what I’m seeing, and as far as I’m concerned it might just be what the title suggests.

Is it making a comedy out of a tragedy?

Well, every serious situation also has a funny component. But I wouldn’t call the show a comedy, even though there are some satirical elements to it. It's more a tragic comedy, with all its melancholy and glam. There’s no good joke without a serious baseline. I’m drawn to big subjects in seemingly simple things. Andy Warhol was, and still is, the master of that.

I’m in the city of his ghost — what about him?

I have admired both his work and him for as long as I can remember, he is a master at creating beautiful things.

I wouldn't call the Campbells all too pretty.

Really? I think it's the most beautiful and poetic painting. Concept and visuals are all the same to me, and his ability to anchor and address and then deliver on those messages — that fascinates me. That’s beauty. Soup has never looked so glamorous.

Then what’s “embarrassing,” you proposed the act of painting as such? Feels like a provocative thing to say.

Perhaps it is. The more immediate the more chance a painting has to fail, but oftentimes that's exactly the consequence of something that has energy; again, it's like standing on a stage, if not similar to an actor once they fall out of character — it ends up being the best part of the performance, because of the energy that came out of it.

Because it's somewhat more true, and honest?

An image doesn’t lie. But I don’t claim honesty to be a criteria, neither in sculpture nor in painting. It’s rather a kind of surrender; we can no longer pretend that something is what it’s not.

I’ll take that.

All I want is to make beautiful things.

You’re obsessed with beauty?

Pretty much.

Says the artist who instead created Everything No One Ever Wanted — we’re unwrapping interesting layers here.

[laughs]

What more to me is how comforting these “vampires” turns out to be, the more one stares at them the more reassuring they feel, functioning as proof to human’s flesh and blood, rather than her robust Chat GPT history — as long as the vampire still wants me, I must be living and alive.

Oh, that's a nice one. I do think that the dark figures, oftentimes the monster, the villain or whatever, somehow carries the most humane stories. They’ve got both sensitivity and idiocy. The gravestones on the other hand, they’re cold. A sketch for the afterlife or the portal to the immortal.