Stored

The series produces an eerie prediction for what's to come. "A day in summer 2020. Social isolation has become normal. The new disease is called hypochondria," says Roché.

Check out the rest of the series below.

Stay informed on our latest news!

The series produces an eerie prediction for what's to come. "A day in summer 2020. Social isolation has become normal. The new disease is called hypochondria," says Roché.

Check out the rest of the series below.

Olivia Kan-Sperling— With poses and faces, people still do this [taking selfie from above] and this [mimics mirror selfie], but —

Chloe Wise— Yeah, we do them differently now. Back then, you didn’t look up into the camera; you looked down. Maybe because displaying your bangs — your scene haircut — was important, so you wanted to capture the crown of the head. Also, because this was the time of skinny jeans, it was about making your legs look little.

OKS— There was also the one, which hasn't come back, where your phone is lower and you're leaning in —

CW— You're leaning in, so your legs go further back, emphasizing a thigh gap. And you’re either doing a peace sign or you’re holding up your hands in confusion, like, “What? Who? Me? Why?" It was performative “awkward.”

OKS— Also squeezing your tits together. No one does that any more. Anyways, it’s interesting that there’s so much overlap between the faces you’re making in these photos and the expressions of the models in Natural Causes.

CW— Actually, when I started working on this show, I was scared it was going to cross into the territory of antlers, twee bands, “awkward” culture, mustaches, feathers in your hair — which is what I was giving, back then, as you can see. Every indie music video had an animal head on a guy with a suit.

OKS— Indie animals were specific types of animals, though. Wild animals. Quirky, authentic animals.

CW— North American animals, particularly: fox, deer, bear, owl.

OKS— The animals in this show are more generic zoo and farm animals: pig, elephant, dog, toucan.

CW— Right. With this show, I wanted to approach a more timeless aesthetic. The stock photos of the kids that I painted are from the 90s, which feels like the aesthetic period we’re more or less still living in.

OKS— At the same time, the adult faces here do remind me of a specific moment in millennial body language history. Maybe a Cobra Snake party photo. These expressions are very different from a Zoomer e-girl bad-mood selfie with a bratty pout. These are people “having fun.” They’re “Party Animals.”

CW— Exactly; they’re consciously representing having fun. These paintings never captured anything real other than the photos we staged in order to become paintings. For example, your smile in these paintings is very much a smile that is aware of itself, not the kind of smile that you break into naturally — like a yawn or a laugh or a hiccup — that takes control of the face for a quick moment, that is fleeting. This is the kind smile that stays, that you count down for, that remains past the point of being what it is.

OKS— What draws you to painting faces?

CW— I don't know what came first, being a portrait painter or being obsessed with faces. I’ve always been obsessed with faces. Maybe that's why I paint. But it’s also that, because I paint, I'm obsessed with faces. The face can express so much, so quickly, with so much more nuance than words can. When somebody consciously puts on a facial expression — tries to look like they're listening, for example — we can read that instantaneously. When you play with kids, the first thing you do is put your tongue out, make a funny face. The human face contains millions of functions, millions of muscles and possibilities. It’s been around much longer than language.

OKS— That’s what’s interesting to me about Natural Causes: you literally put the animal, the pre-linguistic, back into the human face. At the same time, you show that even non-verbal communication is always culturally determined, self-conscious, or unnatural: a type of language. Just like how the words we have for animal noises — oink, bark — vary across human languages.

CW— Verbal communication is so incomplete; that’s why we have body language. I think we yearn for that complete, continuous, pre-linguistic oneness that animals inhabit. I think we fear and envy them for it.

OKS— Is painting closer, for you, to a more “animal” mode of communication?

CW— Maybe if you asked a gestural abstract painter, they would say yes. But I think my painting is closer to language, not only because it's figurative and quite literal, but also because it uses an alphabet of recognizable facial expressions and types of poses.

OKS— Exactly! It's strange to me that critics often emphasize that you paint people you know. To me, your paintings aren’t primarily portraits of individuals. They're more like depictions of social types or emojis — models in the literal sense of being a model of a society.

CW— Usually, the first time I paint someone, I do want to do them justice, so achieving a likeness is important to me. But that isn’t the point of my painting. It’s not like I'm a hired portrait painter. Since I've let go of trying to represent a subject, I’m able to use them as a form or symbol or embodiment of this abstract combination of gestures and feelings. I paint people I know because that’s who's around. I don't get to tell Heidi Klum — actually, remind me to come back to Heidi Klum dressing up as a worm — to come over and put on a scuba mask and take off her panties.

But it’s also that I'm compelled to paint people that I've looked at in real life — to explore specific colors that are happening in this person's face, or that weird look they gave. I'm sitting here and looking at you and noticing all these tones and reflections, painting you in my head.

OKS— Natural Causes is so much about appearances: managing appearances, knowing you're being seen. I remember hanging out with you when you had just spent the morning deleting every photo of yourself from Instagram. But some of them are back now. Why did you un-make that decision?

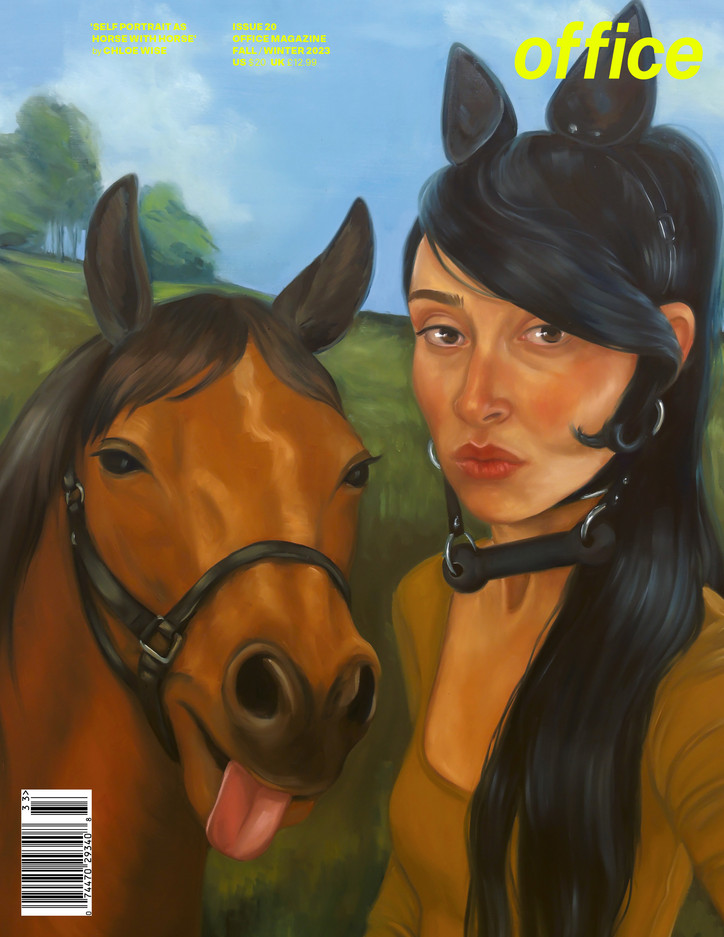

CW— Well, occasionally I just have a random lack of confidence, where I look back at my career and regret the fact that, in my case, the art was never separated from the artist. If nobody ever saw me and I wasn't on Instagram in a horse costume, yeah, maybe my work would be taken more seriously. But why should I not be able to be myself and make rigorous work? To be vapid and silly and playful and intelligent? I want to fight for the ability to possess multiple, seemingly dissonant or incompatible qualities. Which includes the desire to post photos of myself online.

OKS— I think that this also gets at one of the paradoxes explored in your show. Real freedom of self-expression is also the freedom to produce a fake or mediated version of yourself. That’s a natural human desire: to play pretend.

CW— Yeah, and who will care about my Instagram when the earth is charred and unlivable? Who will fucking care that I showed how much fun I was having in my Skims outfit? Oh my God — I just bought so much Skims yesterday —

OKS— Wait, yeah, I want to talk about Skims … Is there anything else you want to —

CW— The horse outfit in the cover painting is Skims. I just sewed hair extensions on the ass as a tail. It’s literally a ponytail.

OKS— That was your Halloween costume last year, right?

CW— Yes — which totally relates to the show. Halloween is this amazing ritual where we get to shed our identities, knowing that we’ll come back to them. Humans have always been doing this, whether it's Carnivale or Day of the Dead: creating a moment where the order of things is temporarily reversed. Chaos is produced as a treat so that you can be a more complacent, civilized subject when the clock strikes midnight and you take off your costume.

Sex is similar: a type of playtime or role-play or sanctioned discontinuity within daily life. That’s why the adults in these paintings are nude. (Interesting that Halloween, for adults, is about sexy animals.) For most people, BDSM wouldn’t be fun if it were their whole life. It has to be a kind of recess from your standard subjectivity.

I’ve been interested in Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of becoming-animal. “Becoming,” for them, does not produce an end-result. If becoming-animal were to reach its conclusion, if the human can no longer remove their mask by choice, that’s where horror and violence come in. That’s a werewolf. But when you dress up for fun, it’s the process of becoming-animal that is at play: you’re neither Chloe nor Horse, you’re the third term, you’re “being both” — which is becoming. That’s why I chose to paint these portraits as floating heads, without a background that indicates where these moments are happening. I wanted to show this ambiguous space where you’re literally suspended between worlds. A continuous space. That middle ground is what language cannot describe. And I think that's what art can get to.

Games are also where we get to negotiate realities from our daily lives we couldn’t confront otherwise. I think that we need these rituals on a foundational level. The object of the animal mask reifies the fact that you are not, in fact, an animal. We play as animals in order to be more human. When we do that, we’re also tapping into the kind of pre-individual unity or oneness that animals, for us, represent. On Halloween, we rarely dress up as a specific horse. We dress up as “Horse” — a generic, general category. So we’re not just taking a break from our own individual subjectivity, we’re taking a break from subjectivity, period.

OKS— I think this ties back to selfies and photos in a way: I like taking photos of myself because it introduces a rupture into that continuous present; it’s like a break from consciousness. And it’s funny that people at parties usually feel more free to behave bizarrely if they’re being recorded. The camera is like a mask or alibi: “This is just who I’m pretending to be for TikTok. Of course I wouldn’t randomly do the worm.”

CW— Totally. And speaking of worms — here I can finally get back to Heidi Klum — remember when she dressed up as a worm for Halloween? I should paint that. That costume was amazing because she came too close to actually becoming an animal. She went past the safe sort of playing pretend and into the grotesque. She actually looked like a worm. That, for me, is where art and humor and beauty and real meaning begin.

I go so hard with costumes, too. This year I want to be Dr. Evil. I’m such a theater kid, which is always revealed on Halloween. I even have this monologue memorized. Ready?

“My childhood was quite standard, really. Summers in Rangoon. My mother was a 16-year-old French prostitute named Chloe with webbed feet. My father was ...”

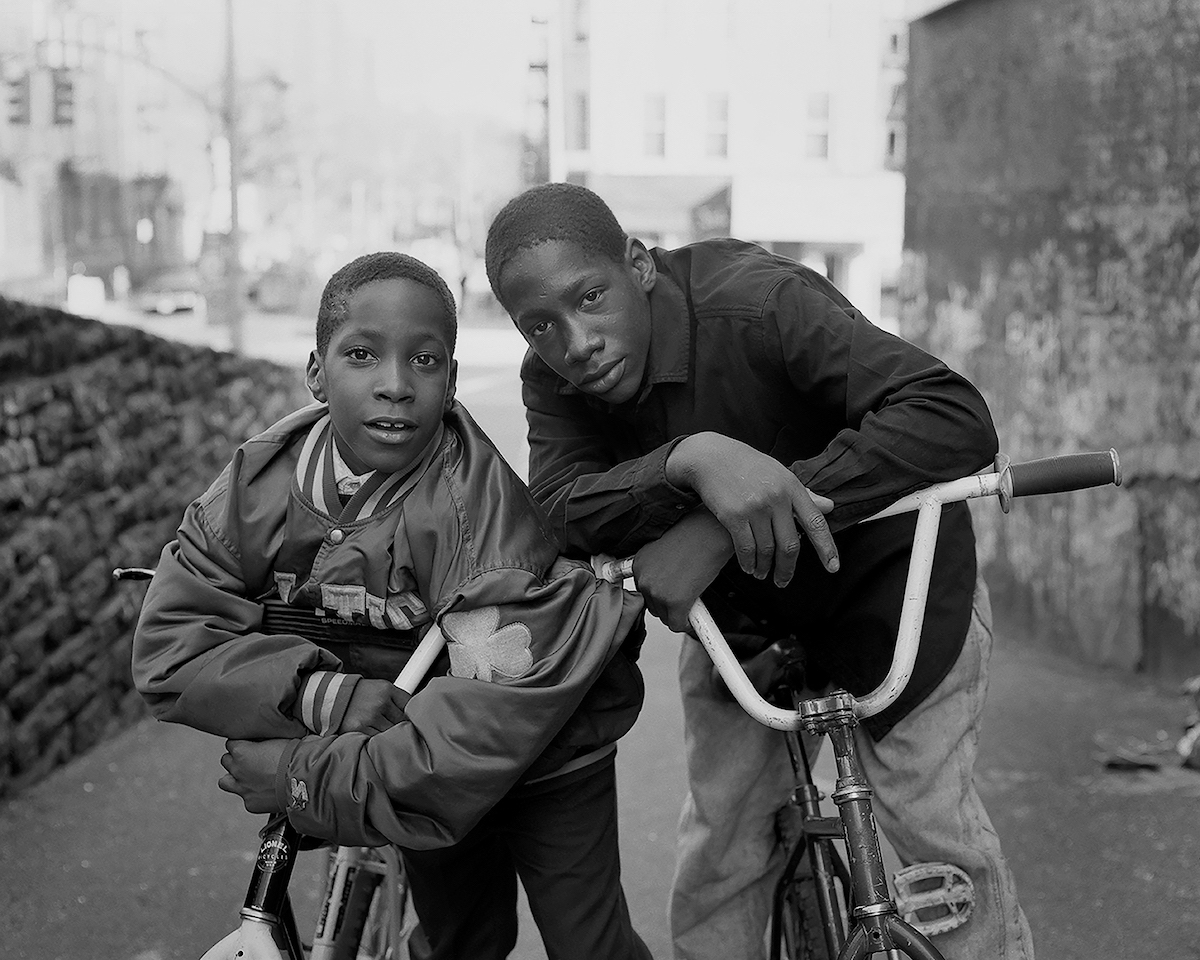

Returning for its third year with another series of portraits documenting the Harlem community through public outdoor exhibitions, the organization expanded the number of featured youth photographers this year from three to five. Now registered as a 501c-3 nonprofit, their mission is to provide accessible, cross-generational cultural experiences for communities of color. “We should invest in the medium of photography today, and make sure that we don’t erase our own histories because gentrification is happening before us,” Sade says. “Harlem has been gentrifying so quickly.” Sade, who moved to Harlem in the 90s, sees a parallel between the aims of her work as Chief Curator of Faces of Harlem and the preservative legacy of work by artists like Gordon Parks. “There is no permanency – years down the line, these people may not be there, these places may not be there — but photography is like augmenting time geographically, historically. When we look at photos from 40, 50 years ago, we’re in awe. But that work is happening right now in contemporary photography.”

Photos by Kaila Burke-Ozuna

Photographer Kaila Burke-Ozuna was a part of the Faces of Harlem exhibition in 2022, posing with her father for a portrait by Xavier Scott Marshall. When she realized that the photographers were selected from an open call, she decided to submit herself, leading to an unexpected friendship with Sade. “We talked on the phone after I sent my application, and we ended up being like, ‘Oh shit, we live like three blocks away from each other!’ This woman has been here in my neighborhood for all these years! We just really hit it off, and in the last couple of months, she's turned into a type of life mentor.” This year, Kaila’s work was featured in the exhibition at Morningside Park. She describes her work as “an ode to folk Catholicism and faith in Afro-Caribbean communities in Harlem."

Placing artists and their works in intergenerational conversation with one another is another guiding principle of Faces of Harlem. Japanese-born photographer Katsu Naito moved to Harlem in the 1980s, and has documented for the nearly forty years since. He originally lived on W 112th Street and St Nicholas Avenue, the same block Kaila would grow up on two decades later before the two would exhibit their photos alongside each other.

Photos by Katsu Naito

Sade hopes that as people recognize the archival value of the exhibition, Faces of Harlem will be able to obtain greater financial support from arts institutions. “Funding obviously is key, from organizations and corporations. Unfortunately that has been lacking and it continues to be lacking because what I have seen is that funding is given to bigger organizations which are not necessarily non-profit and not really serving the community in this kind of way,” she says. “From a historical perspective, years from now people will go back and say, ‘Oh my God, we've created a record of who these people were.’ But it takes many, many years for people to appreciate and recognize these kinds of projects.”

Sade and her Co-Curator Madeleine Budd sought to make the works as accessible as possible to a wide audience, inspired by the artistic history of the Harlem Renaissance and the diverse multicultural vibrance of Harlem’s residents.

Uninhibited by the spatial boundaries imposed by a traditional gallery space or arts institution, Faces of Harlem’s street exhibition model allows it to reach members of the community who may not have sought out the arts themselves. Setting the photographs outside of the park allows the exhibition to belong to the public. This “for us, by us” ethos informs the open call and consideration process as well, prioritizing clarity and authenticity of vision over the orthodox and often prohibitive criteria of the fine art world.

Installation photos by Alex Bershaw

A full list of 2023 Faces of Harlem contributors can be found on the Faces of Harlem website.

How did Lima and its culture influence your photography while growing up?

I grew up in a very communal environment that had a profound influence on the way I approached photography. When I was a kid, one of my fondest memories was waiting for the clock to strike 4pm. All the kids from the street would call my brother and me to come out and play some activity like “trompo” or “canicas” until it got dark, and our parents would shout for us to come back home. We knew everyone on our street and the next one: our lives revolved around community. Life wasn't easy there; everyone was in similar circumstances, and what we were left with was the need to come together and truly understand the value of having each other. This laid the foundation for my upbringing. Community was incredibly important.

Could you unpack your heritage and what it was like growing up in your country?

Lima is a city where the past and present coexist. While growing up I was exposed to various cultural traditions and festivities that were incorporated in school. For most of my childhood, I lived in a small town on the outskirts of Lima, in the district of Mangomarca. Every summer, during the month of February, all of Peru would celebrate "carnival," a festivity used to mark the last few days before the Lenten season in the Christian calendar. For kids, it was celebrated with an ongoing water balloon fight throughout the month, along with dancing and music. Each region put its own spin on it, making it a lively and colorful celebration. It was my favorite time of the year as a kid! My grandma grew up in Yurimaguas, which is in the northeast of the Peruvian Amazon, and that had a significant influence with Amazonian traditions. These included traditional dances, cuisine, music, and even natural healing practices. It was pretty cool to have been exposed to such a diverse range of customs during my childhood.

What are your key messages that you like to convey in your practice?

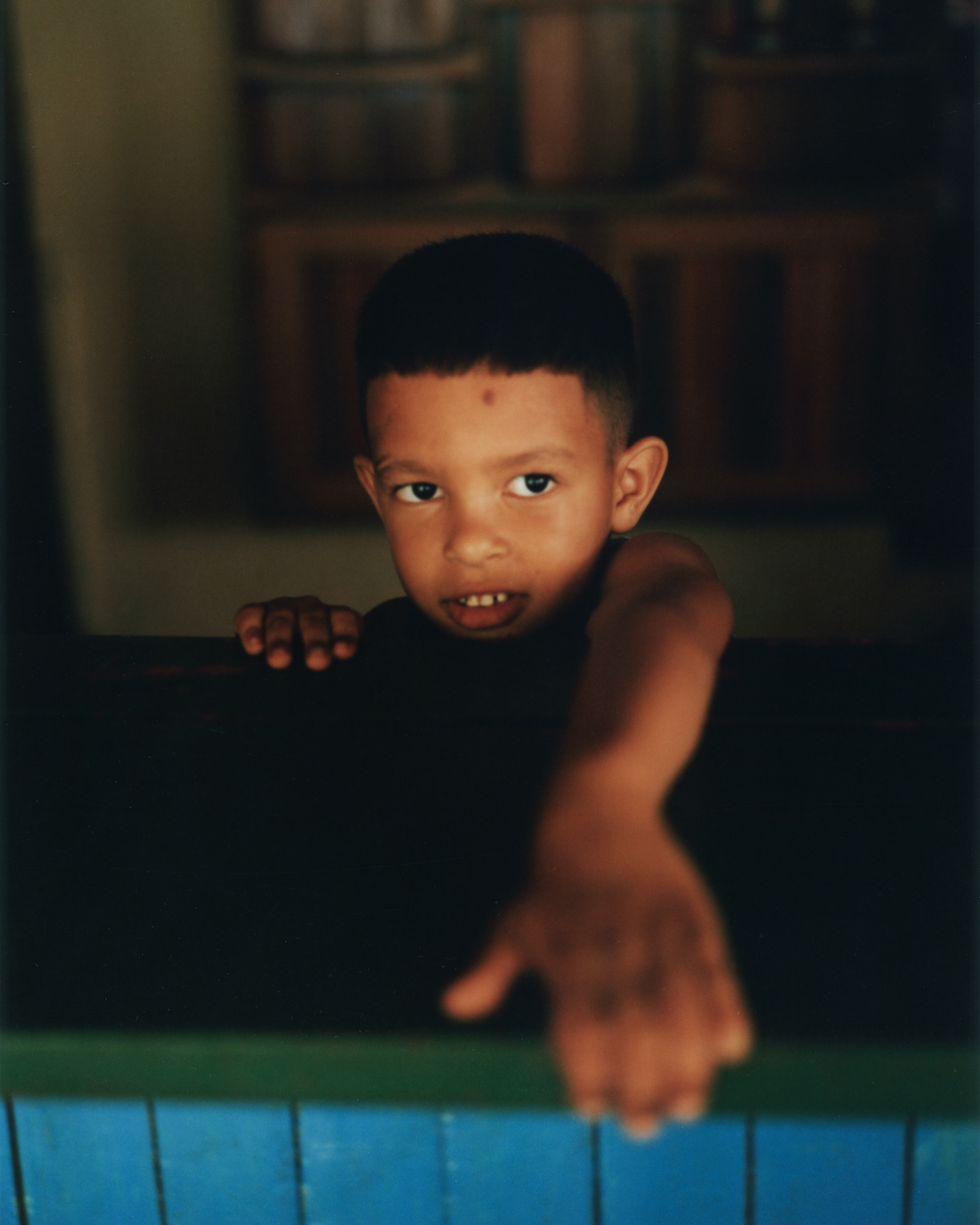

A message I always try to convey is intentionality. Taking a photo, for me, is about mutual giving. In some of the most intimate images I've taken, there was a lot of trust involved from both sides. I often ask myself why I take photos, and it's these kinds of projects like De cara al sol that give it meaning. To be able to share photographs that speak a universal language, ones that could influence action, stimulate understanding, or evoke a feeling.

I have always seen this medium as a doorway into sharing my experiences. It is our upbringing and influences that shape our interests and make us unique. From there, each of us take our own paths and become interested in shooting subjects that remind us, in some way, of a part of our past lives or younger selves.

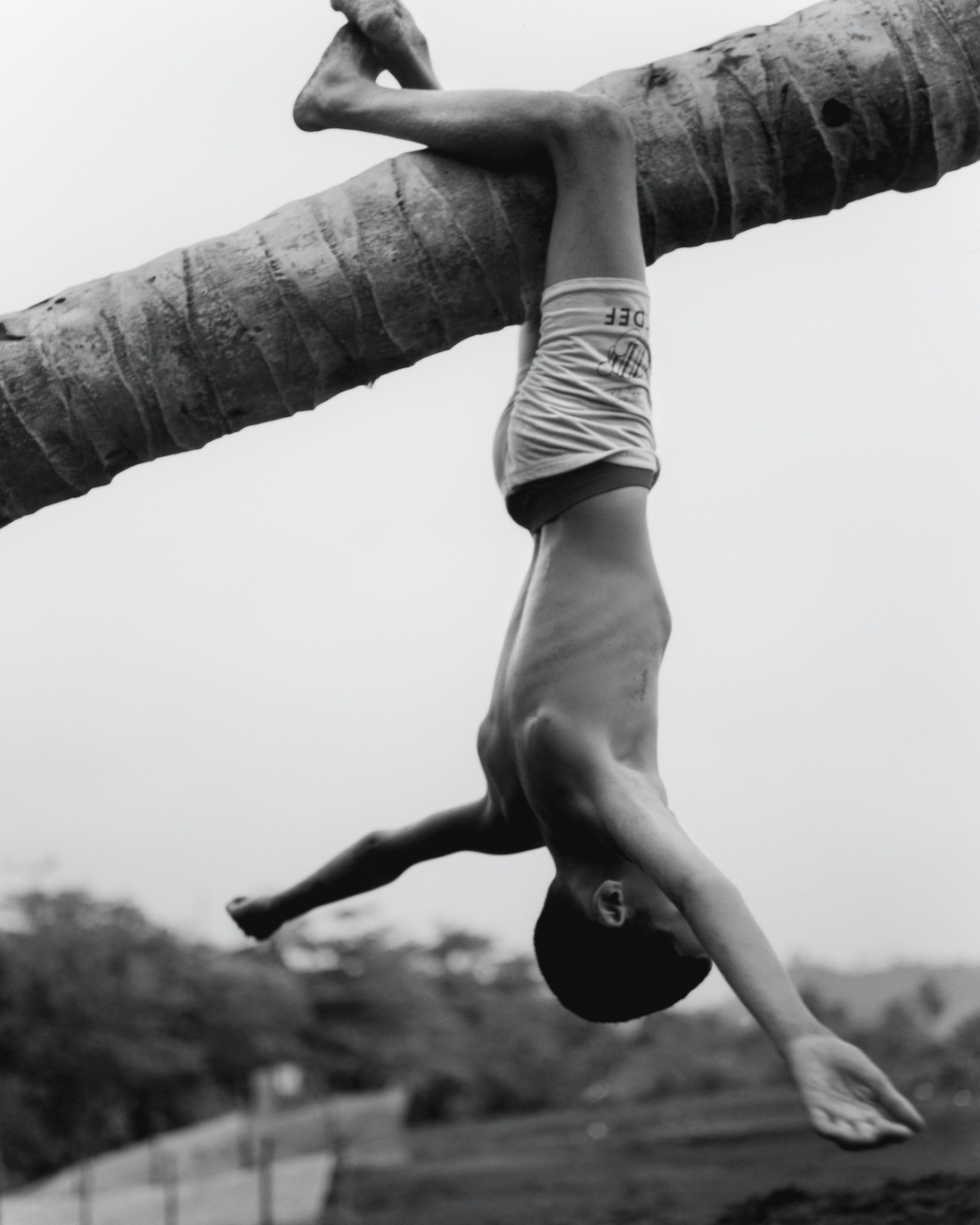

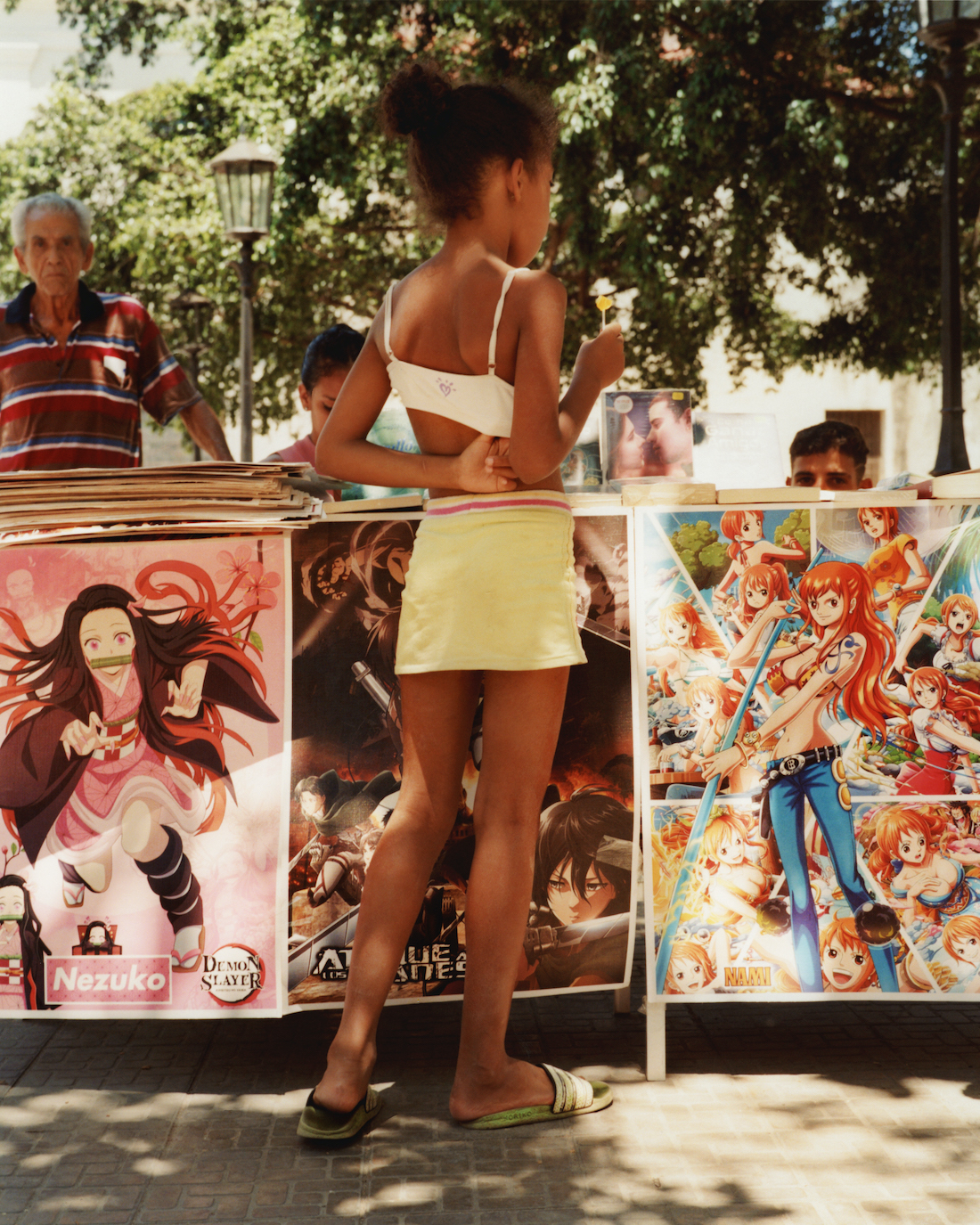

De Cara Al Sol is the title of your new book. What were your inspirations and references?

The title was inspired by one of Jose Marti’s poems, "Versos sencillos XXIII,” which is part of a series of 46 poems. In these verses, Marti talks about his experiences throughout different stages of his life and expresses principles and assessments about nature and poetry. Jose Marti is considered one of the most important figures in Cuba and a key factor in Cuba's fight for independence against Spain. It felt right to pay tribute to his work.

Why Cuba? What aspects do you find compelling?

I discovered a sense of familiarity while in Cuba, it uncovered a childhood feeling that resonated deeply with me. Initially, I had no intention of starting a project about Cuba. However, visiting and immersing myself in their culture sparked a profound curiosity, inspiring the creation of this project. I emphasize this point because I consider it crucial: it's the strong bonds they share and what 'community' truly means to them. It resonated with me, and I felt it deeply. Even as an outsider, they welcomed me with open arms. At its core, Cuba represents the strong sense of community and the love they have for one another. It's a beautiful feeling to be a part of. Their energy is truly magnetic.

What was your key focus while building the book? How long did it take?

A key focus for me was publishing this book under my new creative studio, AMILE, which I founded with two friends. It's the first creative project undertaken by the studio, and it's incredibly exciting to create and publish a book with a team of like-minded creatives. We spent approximately four months designing the book, along with some other projects that coincide with it. It has been a highly rewarding journey. This whole project took approximately three years to create. Most of it is derived from my most recent trip to Cuba. During my initial visits, I focused primarily on absorbing the culture. I realized I had to cultivate a profound knowledge of the island, not only from my point of view as an outsider but also to comprehend the Cuban perspective. This involved building relationships and gathering stories to effectively convey through this book. The objective is to immerse you in a sense of curiosity, encouraging readers to explore further, to draw inspiration from these stories, and ultimately, to visit Cuba. It aims to kindle an interest in the island and its unique charm. It serves as a reminder that, now more than ever, we need each other and a sense of community. The Cubans demonstrated to me how simple happiness can truly be.

There’s a recurrent theme of nature that runs through the book. Why does it play such a huge part?

It naturally evolved this way; I feel most alive and fulfilled when surrounded by nature. I find great peace and clarity within it. It transports me back to a simpler memory of my childhood. Nature has the power to humble and ground you. In Cuba, I felt so attracted to the unique and untouched nature the island holds.

What’s your favorite photograph in the book? Why?

It would have to be the image of the kids in the playground, primarily because of the feelings it evoked while I was there. During my travels in Cuba, various encounters would stir emotions that led to memories from my past. This particular image serves as a vivid reminder of a time when I was a child in Lima and the clock would strike 4pm, and my brother and I would run outside to play with our friends.

What’s next for you?

What's next is our focus on organizing various exhibitions and activations for 'De Cara al Sol' across the US, Mexico, Europe, and the UK, all while sharing these profound stories with the world. I'm also excited about creating more philanthropic projects under AMILE. The two friends I'm starting the studio with bring unique backgrounds to the table, and together, we aim to make a positive impact.

And your future hopes?

I hope that this project has an impact on the Cuban community, initiates meaningful conversations, and inspires other creatives to use their talents to effect change — to use our voices to make a difference. I also hope that 'De Cara Al Sol' marks the beginning of a series of books where I can explore more about other cultures. Aiming to promote cultural understanding and celebrate the richness and diversity of our world.