Summer of Something Special

The images, and the book, have us wishing it wasn't 40 degrees in New York. To celebrate its launch, read our interview with the photographer, below.

Tell me about growing up in Venice.

Venice was rough and dangerous, but I wouldn’t exchange it for anything. There were many hard lessons to learn there. When I was young, I really felt like Venice was the world and I couldn’t see out of it or past it. If you didn’t exist within those few square miles you just didn’t exist to us. Our role models were the neighborhood guys—people we actually knew and came in touch with day to day. To my friends and me, Venice encompassed everything we believe we ever needed, so we didn’t have aspirations to leave.

What did Venice look like back then?

Venice was timeless. It hadn’t been touched. Nobody wanted to live there unless they were escaping something. So, it was accepting. I think the connotation was that it was poor and rundown. Opening a business there didn’t seem promising, so everything was mom and pop. You didn’t see large corporations coming in and starting a shop, so therefore there weren’t really jobs. Venice operated on the black market—you could get anything you needed or wanted off the street, from groceries, to household appliances, to pets and school clothes.

What were you like as a kid?

I think I was too adventurous for my own good. I was very independent from early on. I would ride my bike further than we were allowed to go and stay out past our curfew, until the street lights came on. We would bomb the hills on our skateboards by the baseball field, spend our summers at the public swimming pool—which at the time was only 65 cents to get in—scrape together money for the ice cream man, play suicide against the neighbors garage with a tennis ball. And then I would sit and draw for hours—drawing was the one thing I could focus on.

What did your parents do? Did you have siblings?

My mom is a piano teacher. She taught voice and music reading at some of the local schools and churches to the children. She worked at Dorsey High, which was one of the worst schools in LA when I was growing up, and then she went on to work at some of the elementary schools closer to our house. Later, she came back to teaching piano to all the local kids out of our home.

My father wasn’t really in the picture. He left when I was about nine years old and we all became more and more distant over the years with him. I don’t think he was really ever fit to be a parent. He had an abusive upbringing and he never recovered from it. My mother’s father had got him a job in management, which he kept until my teens, but he was laid off when the company folded in the late ’90s. I have two blood sisters and I was the middle child. My mother remarried and had a string of relationships and I grew close with the kids of those partners who became like brothers and sisters to me, too. They lived locally and I’d often stay at theirs because we had less supervision—our parents were too busy being loved up to pay attention, so often we were on our own. We got in loads of trouble—pretty much anything you can imagine.

At what point did taking pictures become important to you?

I think when I was around 18 I was handed a few cameras and I realized that I should document my life a little because I honestly didn’t think I’d be here for that long. I had lost two really dear friends quite young. One friend was murdered when I was 16 and we were at the Emergency Room when she arrived, and then just two years after that I lost my best friend in a car accident. I think through those events I realized how important it was to leave some type of footprint, proof of a life, and I just started shooting honestly, with only that intent. I was able to recover a decent amount of those photos and included them in a show I had in Europe a few summers ago.

What did you initially photograph?

I was mentoring kids in the housing projects in South LA and was teaching them photography. I started to document them on film and let them shoot on my cameras. I would print the pictures out and then bring them the following week to show them. I found that this built up their self-esteem and brought them joy. Concurrently I recognized that Venice was quickly changing and that everybody was leaving or getting pushed out, so I started to photograph all the people, places and things that I felt made Venice, Venice.

You never went to college. Do you think it’s important for an artist or do you think it may actually hinder their creative process?

You know, I wish someone had told me to go to school, maybe for other reasons than actually learning a trade. I do think for some artists school is important, but I also think art school is forced on artists. If you think about the age kids are when they go to these schools, we don’t have a clue who we are at that time. Our identities are still developing. And meanwhile, at school, they’re trying to shape how you think or what you should say in your art. Everyone develops at a different pace. So, I think it does hinder creativity. It’s an unnecessary pressure, when school is already hard enough. Art is so arbitrary. I think school can be a waste for some, if not most.

What did you learn living in London?

How hard I needed to work in order to compete and be relevant at the level I wanted to reach. To me, London is putting out the best work visually at this time and the world adopts what London makes—whether it be in the arts or advertising or film and so on. I think initially I was intimidated being from Los Angeles. I remember going around and showing my book and being told, ‘Oh nice to meet you. We’ll just hire you in LA.’ There were two things I really like about London, and someone can correct me if I’m wrong, but there’s less prejudice in the arts. If you meet a rep or a magazine, they will say, ‘Go do x,y and z. And it would be great to see more of stuff like this in your work.’ If you do what they ask, they will most likely give you a chance. I feel like in America, it’s just the one meeting and it’s done. If you aren’t on their level at that moment, they’ve made their mind up on you and that’s it. Also, concerning gender and race, I feel like London does not care if you are a man, a woman, old, young, gay, straight, transgender, black, white, muslim or whatever—if you are good at what you do, you will be given the opportunity. In America, I don’t find that to be true.

Do you still live in LA?

I never fully left LA and I don’t think I ever fully will. But I did step away from Los Angeles to broaden the strokes of what I’m doing. Los Angeles is home, but I think it was necessary for me to leave LA from my work to expand and to remove a ceiling. I think at the time when I started in photography, Los Angeles didn’t have the respect that it does now and the opportunities weren’t there that exist now. There wasn’t as much of an international cache. Now, I think there’s a romance between the world and LA.

Do you still shoot there?

I am still working on passion projects in LA involving the youth and community. I think in the beginning, that was my location and point of reference for everything, so it was more haphazard. Now, I feel that whatever I do around LA in the anthropology space needs to be really sensitive as to what LA needs—I need to have more tact in whatever it is I do. Being from there, I feel it’s my social responsibility to not contribute to the noise.

Do you think an area can lose something special after it's been shot for too long?

I don’t want to document something over and over again that so many others have documented, unless I have a really different, unique way of seeing it. I think discovery is a huge part of photography and half of what makes someone a good photographer, regardless of your technical abilities, is your ability to find subjects and places that people haven’t seen before—introduce people to them. And it’s your ability to connect honestly with those subjects.

Where did you take the photos in the Summer of Something Special book?

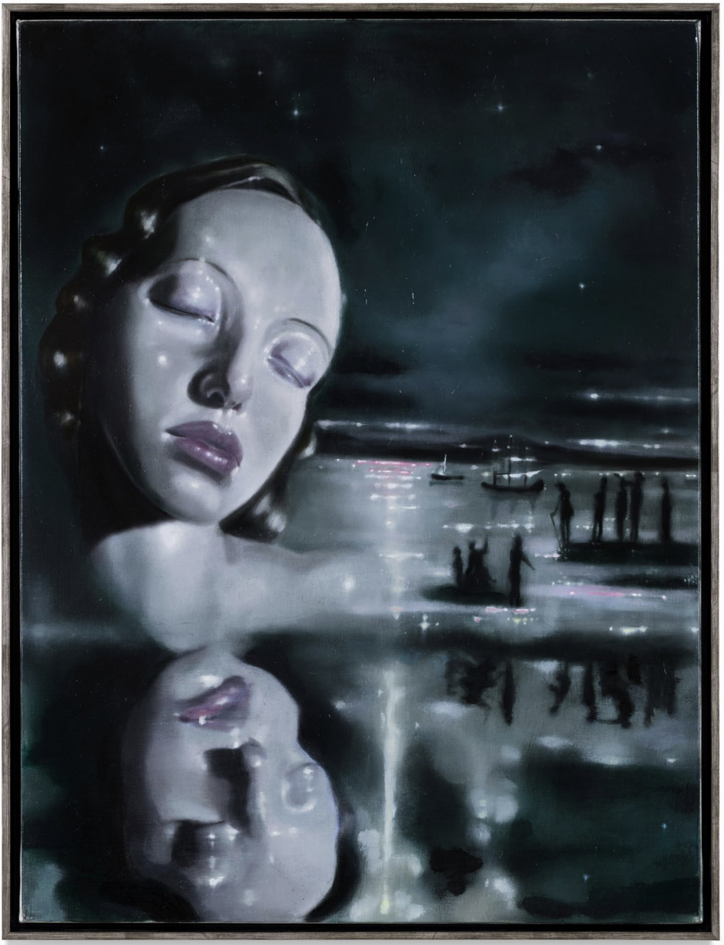

These photos are from Port Royal, a small fishing town that looks at Kingston.

Tell me about Jamaica—what's it like?

EVERYTHING is done on island time.

What did you love about the people and the culture?

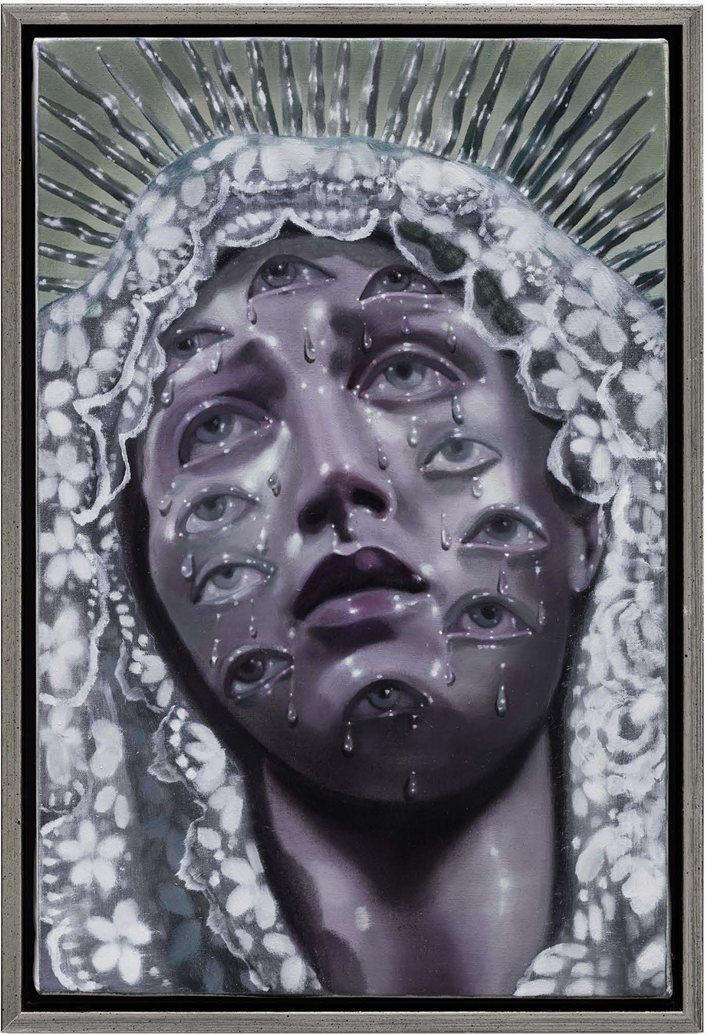

What I loved about the people and the culture was the honesty. It’s very obvious that they feel they only have each other. Most of these kids, they’re just on their own—they’re raising themselves. The communities are so tight-knit that, whether they are related or not, everyone treats one another like brother and sister.

Tell me about the girls that are in so many of the photos.

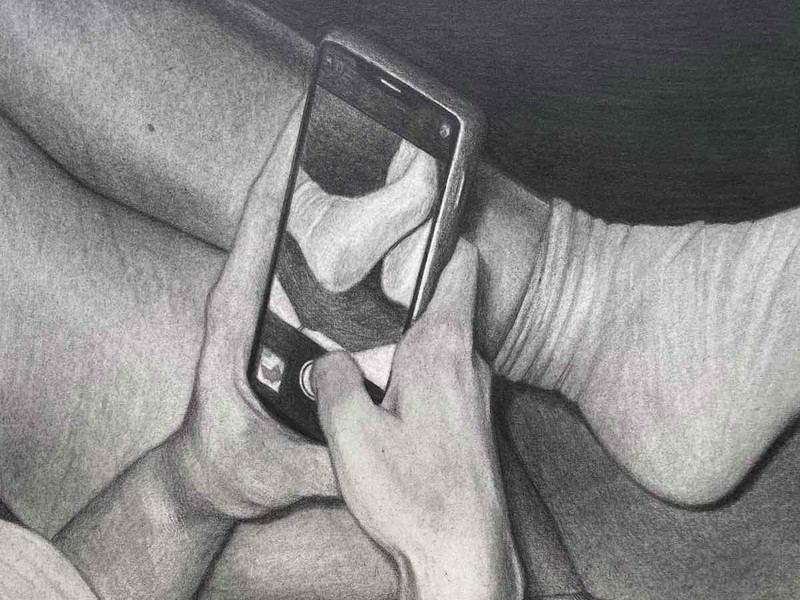

I loved the sense of wonder they had. They were really fascinated with me and my team. They wanted to know about all the cameras and look through them, and see how they work and look at their friends through them, and see themselves through them. There was just something really natural about our interaction. They had this amazing bond between the two of them. You could tell that they really love each other. It was hard for me not to capture it.

You have a book you've been working on for years, right?

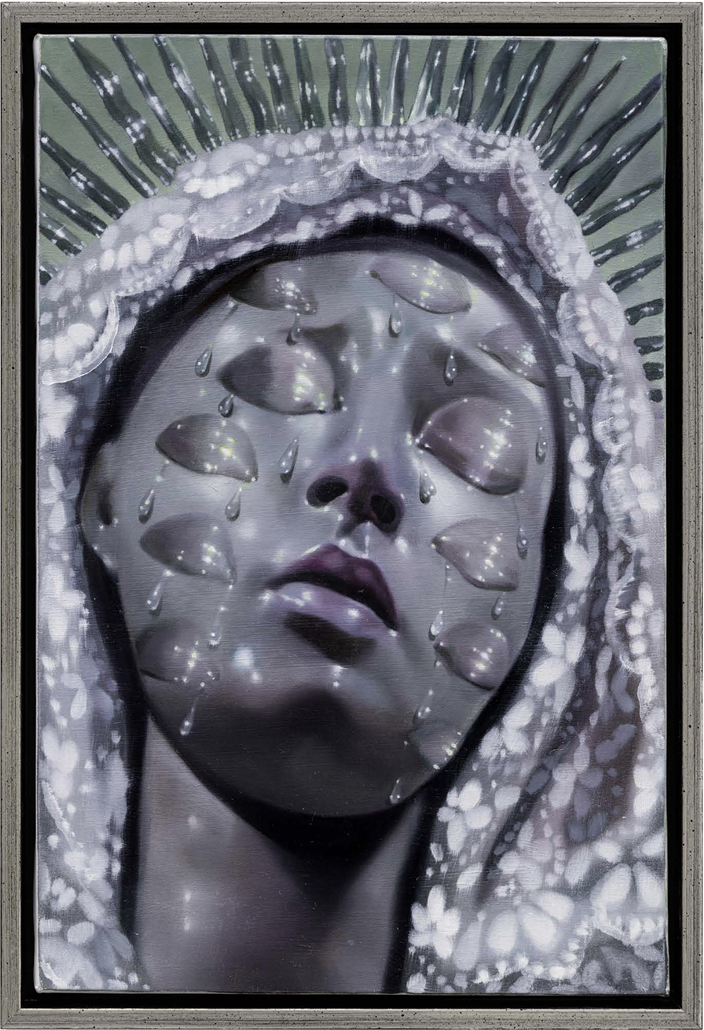

Yes, it’s comprised of my photos that span from when I was 18 years old up until today. I feel like I’m never finished with this book—I just continue to add to it. I feel like I’ve gotten better and my work has progressed over the years in terms of aesthetics. The feeling and sentiment behind the book hasn’t changed, but I do think that I’ve been able to say more of what I want to with my more recent work. The book contains all of my personal work. It’s essentially a document of my personal life—past relationships, youth, my neighborhood, letters, writings, drawings, my family. It’s an extremely personal project. Hopefully, next year I will release it.

'Summer of Someting Special' is available now, with all proceeds benefitting the ACLU. Buy it here.