SUPER/office Premiere Party

As the debut of the SUPER/office sunglasses, and premiere screening of office's accompanying video, the event drew a crowd of close industry friends and fans of both brands.

Special thanks to Old Blue Last.

Stay informed on our latest news!

As the debut of the SUPER/office sunglasses, and premiere screening of office's accompanying video, the event drew a crowd of close industry friends and fans of both brands.

Special thanks to Old Blue Last.

As the co-founder of Dream Baby Press, Starr champions a kind of do-it-yourself, populist poetry that can be written and ingested on-the-go. “There is no barrier to entry,” he says of Dream Baby’s literary events — an earnestness that is sometimes hidden in MOUTHFUL’s casual, almost indifferent whimsy. Office spoke with Starr about the role of humor in MOUTHFUL, the trials and tribulations of indie publishing, and Dream Baby’s experimental future.

Terry Nguyen— You wear so many hats, as a producer (for your day-job at Substack), editor, small-press founder, and now poet. When did you start writing poetry?

Matt Starr— I started writing for fun and for myself starting in 2016, 2017. Around the same time, I was making a remake of Annie Hall that starred seniors with a cast of 80- and 90-year-old actors as an art project. I totally fell in love with older people while making that and became best friends with the star, who was 94 at the time, and we remained close until he passed at 99. That experience really changed my life. And throughout, poetry has always been in the background. Then, the pandemic hit. I got dumped. I moved to the Upper West Side, and there was no opportunity to shoot, since we were working primarily with older people. I started reading a lot more poetry, writing a lot more poetry, and it was the first time where I felt in control creatively, where I didn’t have to ask other people’s opinions as to what I wanted to put down on the page. I was really writing to make myself laugh. And it was the first time in a long time I was having fun making stuff.

How did you come to write and produce this collection?

During the pandemic, I was living near Central Park, and I would run around topless. I felt so free. Nobody was around. One of the themes of MOUTHFUL is body issues. I was reading a ton of poetry and running around, and while on jogs, I would dictate into my phone, and that's kind of how it all started. All of a sudden, I realized I had hundreds of poems.

During this time, Zack [Roif] and I started Dream Baby Press. We started it because we wanted to throw literary events that were fun and exciting and shared our sensibility and ethos. There is no barrier to entry. You didn’t have to like poetry to come to our events. You didn’t have to read poetry. I was reading a lot of punk biographies and I really aligned with the DIY ethos of punk. I wanted to follow in that tradition.

I ended up getting a book deal, but turned it down and then that publisher became an important mentor along the way. I wanted to learn how to make a book, and it was important to me that before Dream Baby publishes anyone else’s book, I should probably learn and make all the mistakes with mine. I got Elinor Hitt, a PhD candidate at Harvard, to be my editor, which was a huge boost of confidence.

A few poems in MOUTHFUL are published in the New Yorker’s humor section under the title, “Some Poems About A Girl I Like.” This is kind of an obvious question, but do you intend for your poems to be funny? (One of my favorite lines is from “Home on the Range.”) What’s the role of humor in your work?

At the launch, [my girlfriend] Mackenzie Thomas gave a speech, where she said, “Matt writes to make himself laugh.” I think I really needed laughter and humor in my life when I was writing these poems after a breakup. The poems and writing I gravitate towards are not self-serious. I think the Trojan horse in my writing is humor. I'm not intentionally trying to be funny, but I think it's like, Why does somebody walk the way they walk or talk the way they talk? Fun is also really important to me. I wanted the process of making and writing these poems to be joyful.

I started reading publicly and performing in 2020 once things opened up, and people would always come up after an open mic and tell me they liked what I did, even if they didn’t usually like or read poetry. I didn't get an MFA. I was not trained as a writer. I studied conceptual art. But I think the throughline with all my work is a sense of humor and sincerity. Even if there is something taboo, I like there to be a sweetness or humor to soften the edges.

“Self Portrait” is a poem about a self-portrait that the speaker’s child self tries to draw. What’s the lore behind the poem and the Bambi drawing?

I was in the special ed for most of my childhood. There was not a lot of schooling going on, but this one teacher, Ms. Levitt, would let us chase our interests and I became really obsessed and fixated on things. Bambi with boobs was one of those images I would draw over and over again. Being in special ed taught me so much empathy and nobody wanted to be there, but I really treasured that time in my life.

There’s another poem with a Marge Simpson drawing at the end. I didn’t draw that but I paid this kid to draw Marge naked. Back then, you had one home computer and porn just wasn’t as accessible. We had printouts we gave out at the opening, and in the drawing, you can see how he drew my hand over her breasts and I made him erase it. I think it's because I wanted to see her full, bare breasts and not have it be obscured by a hand. I just wanted the whole thing to be as horny as possible. After she read the book, I think Jemima [Kirke] said this book is about shame and owning that feeling. It’s about finding the beauty in shame and discovering myself through all of that, and it’s cool how there’s evidence in the drawings to point to.

Autofiction is a hot topic right now. Almost every writer I know writes from personal experience, but some are more quiet about it than others. MOUTHFUL sounds diaristic, but I’m not going to assume it’s all autobiographical. How much of it is “real” vs. fiction?

I don’t really know much about autofiction. I’ve heard the term, but I don’t know what it means. For me, I write from two places: diaristic and fantasy. Because of where I was at while writing MOUTHFUL, I really lived in my head, and a lot of my poems became manifestations of the fantasies I was imagining. Some have been worked through and I have successfully lived out some of these fantasies, but it’s a balance. Some are partially diaristic and some are partially fantasies I’m having and working through.

A few poems in MOUTHFUL are written in a list format. Others are very informal and short. Were there any poets or writers that you took stylistic inspiration from?

I was really drawn to Peter Orlofsky, Richard Brautigan, and Renee Ricard. I love how you could open one of their books and see the world in a different way and each had their own sense of humor in their poems. Sometimes there’s spelling mistakes or drawings and they’re serious artists but I don’t know how seriously they’re taking themselves, you know? It feels like they’re having a lot of fun.

Because of my background in film, I think I approach my poems a little bit like cinema. I think visually about what’s happening and how to write a scene. But in terms of inspiration, I got it from Nora Ephron and the romantic comedies I was watching. I was reading a biography about Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground. And as I was falling in love with Mackenzie, her life became like poetry to me.

I love lists. I love how a list reminds me of an old recipe from Julia Child. I love seeing how information is codified and put together in that way. Visually, it’s just so beautiful. It’s actually not fun to read those poems out loud, but looking at them is beautiful. I love working through some ideas almost mathematically in a list. It's almost like a thought problem, but to me, a list is such a poetic way of thinking through and connecting ideas and feelings.

This is your debut book and Dream Baby’s first release. What’ve you learned during the process of publishing your own work?

The actual writing of the book, I think, was the easy part or rather easier part. I have this joke with myself that indie publishing made me hate indie publishing because making this book kicked my ass for a few months. I also wanted a specific look and feel to the book, but I had to learn how to communicate all these things to a printer. Like, I wanted the paper to feel like paper: eggshell white with natural paper stock. The process took so long, and it took many attempts to get there.

Dream Baby isn’t really a business and I’m not a designer. I had some really good friends step in to help me and give the book support. Publishing is really hard. That really surprised me. There’s no Warby Parker version of making a book yet and I have so much respect for anybody who takes the time and effort to publish independently. It’s really fucking hard.

What’s next for you and Dream Baby?

We have a couple of books lined up for Dream Baby. I’m really excited to be going to battle for another writer and have a little distance from the process because I was so pedantic and neurotic about my book. I worked so hard for what appears to be a very simple book. Now that I’ve learned the language, I’m excited to put that to work for the other writers we have on board.

Dream Baby is in a great place. We can do whatever we want, and I’ve gotten to work with so many artists and writers I’ve admired. It’s opened up so many opportunities to do fun, weird things. It has this amorphous form, but now we’re publishing which has been a long time coming. We also throw these crazy literary events and I’m excited to push those even further. I’ve been asking myself for two years what my version is of a book launch party and now I know. I spent four months putting it together, and it was one of the best nights of my life.

We didn’t set out Dream Baby to become what it’s become. Sure, it’s a little more erotic and set in weird spaces, but there was no expectation. I really like sitting in that experimental space where we can say yes to collaborations with people who we find interesting. I have no idea what’s going to happen, but that’s what I find so exciting.

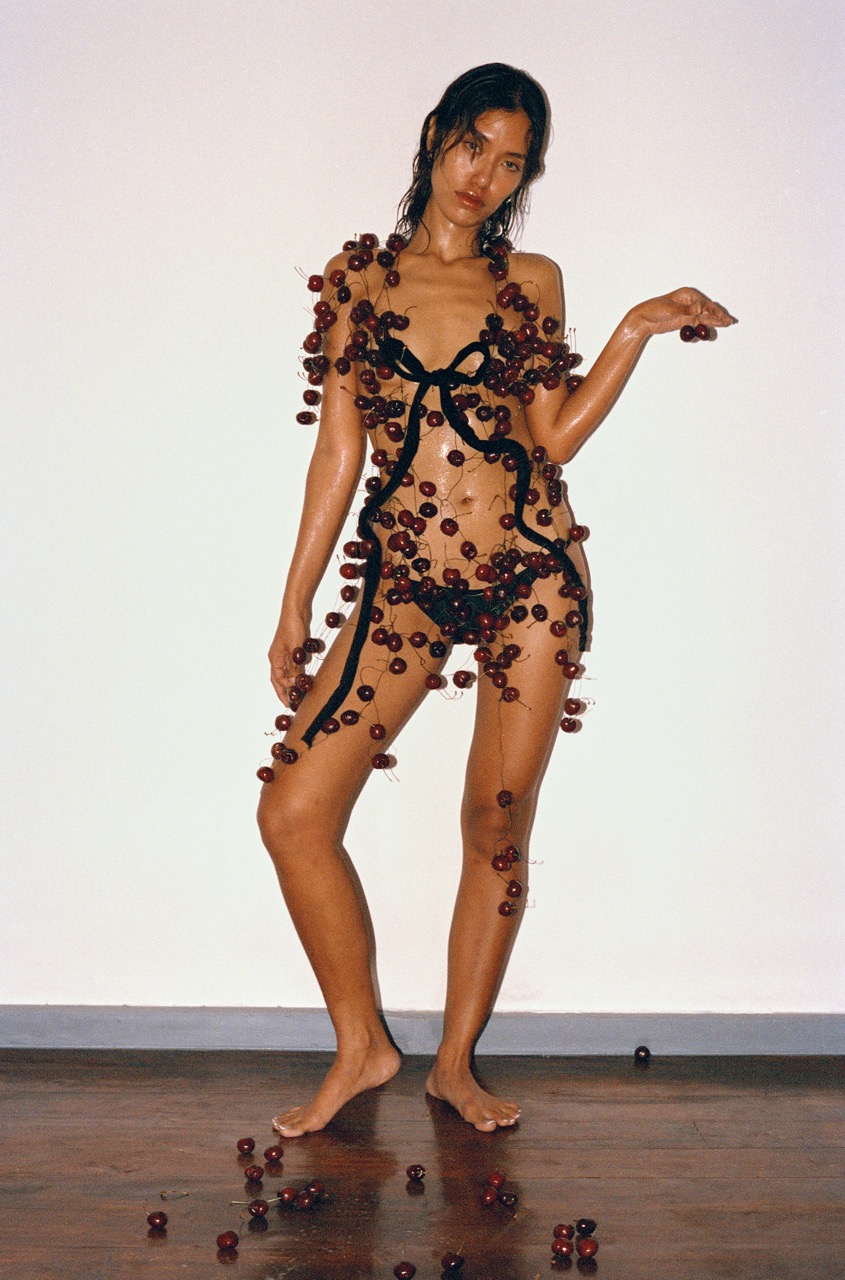

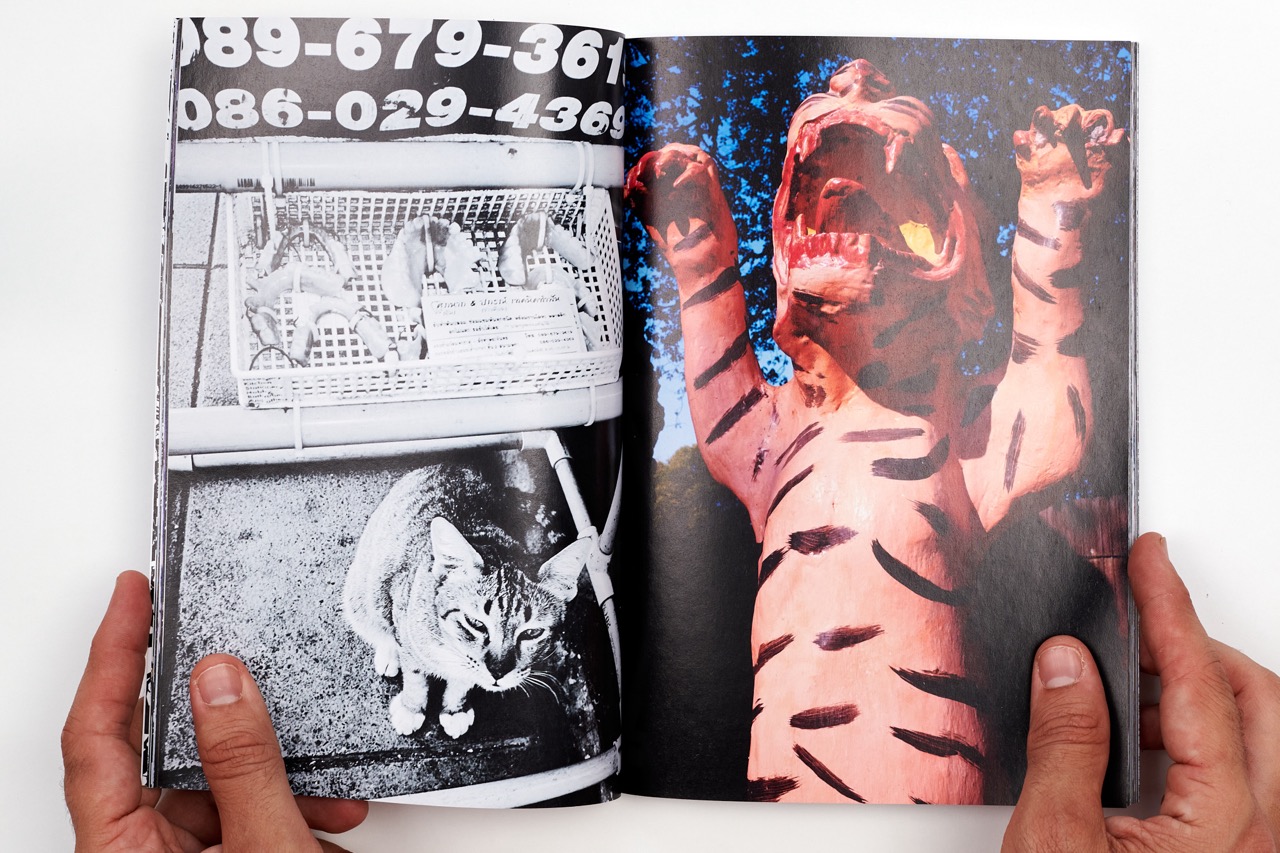

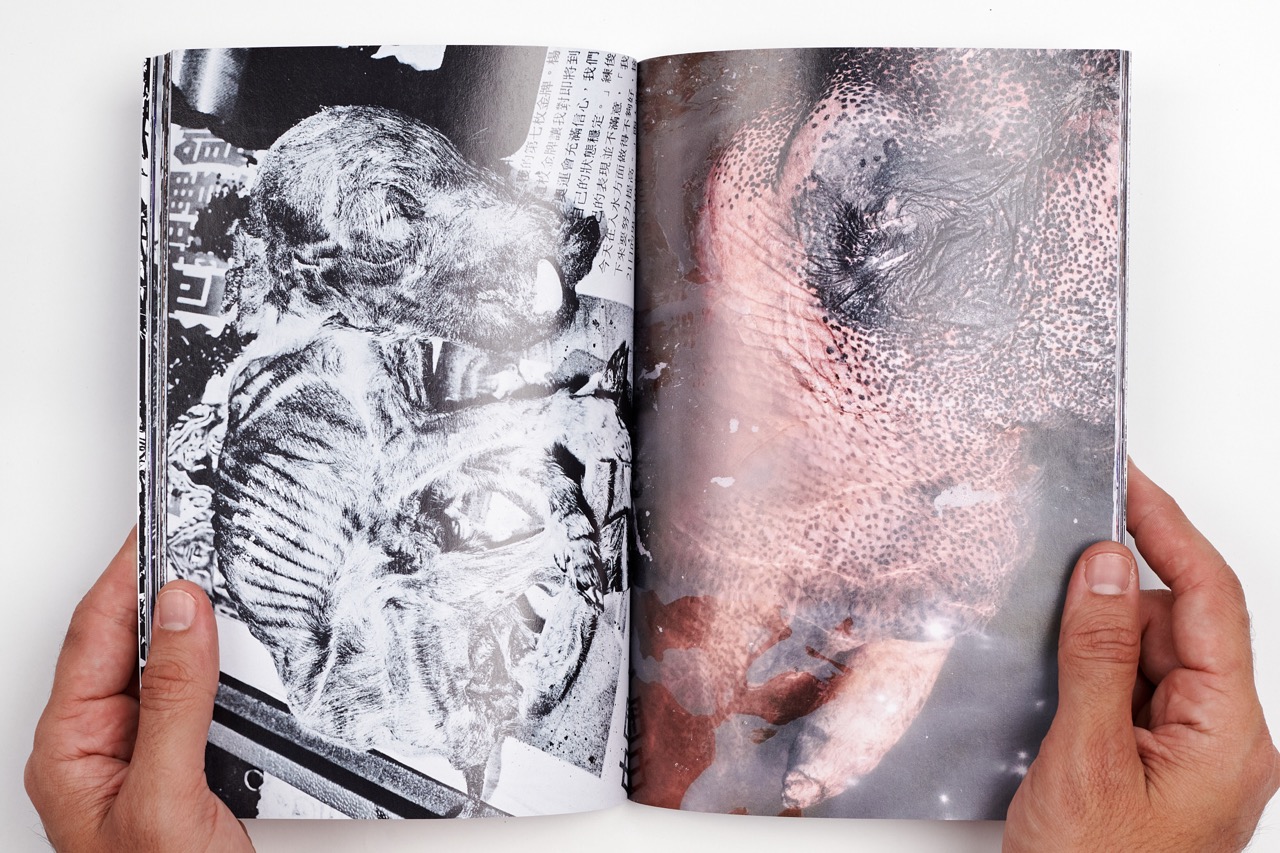

The project, published by Michael Krim’s Paper Work NYC as an 88-page book, will be celebrated with a launch event at Paper Work's flagship in LA’s Arts District on August 23rd from 6-10 p.m. To mark the occasion, 6ft x 4ft-16ft long posters featuring imagery from Banana Cries have been plastered across Los Angeles, inviting the public into the world Landis has captured. The images — a striking mix of surreal fashion and organic materials — embody the project’s themes. From a figure crowned with a headdress made entirely of bananas to a model adorned with fresh flowers and serpentine accents, each shot blends the organic and the artificial, the beautiful and the grotesque, reflecting Landis' fascination with the contrasts and contradictions that define our existence.

Banana Cries is available for purchase from Paper Work NYC here.

Qingyuan Deng— Hi Jason. Should we start with how you conceived this project, which follows your tradition of exploring a country, its landscape, and its people? This time, however, your project seems more collaborative, especially with your work alongside Eric Tobua.

Jason Landis— In my past work, I strategized concepts with well-thought-out plans and a clear vision. But with this project, I honestly stumbled into it. I met Michael Krim of Paper Work in Tokyo a couple of months before, and we immediately hit it off, spending a few days together. Michael then mentioned he was organizing a book fair in Bangkok and invited me to join him. I quickly threw my things together and headed to Bangkok with zero plan.

Banana Cries is the accumulation of what happened while I was there, with a lot of improvisation. I landed in Thailand and stumbled upon Eric’s Instagram, and immediately fell in love with his work.

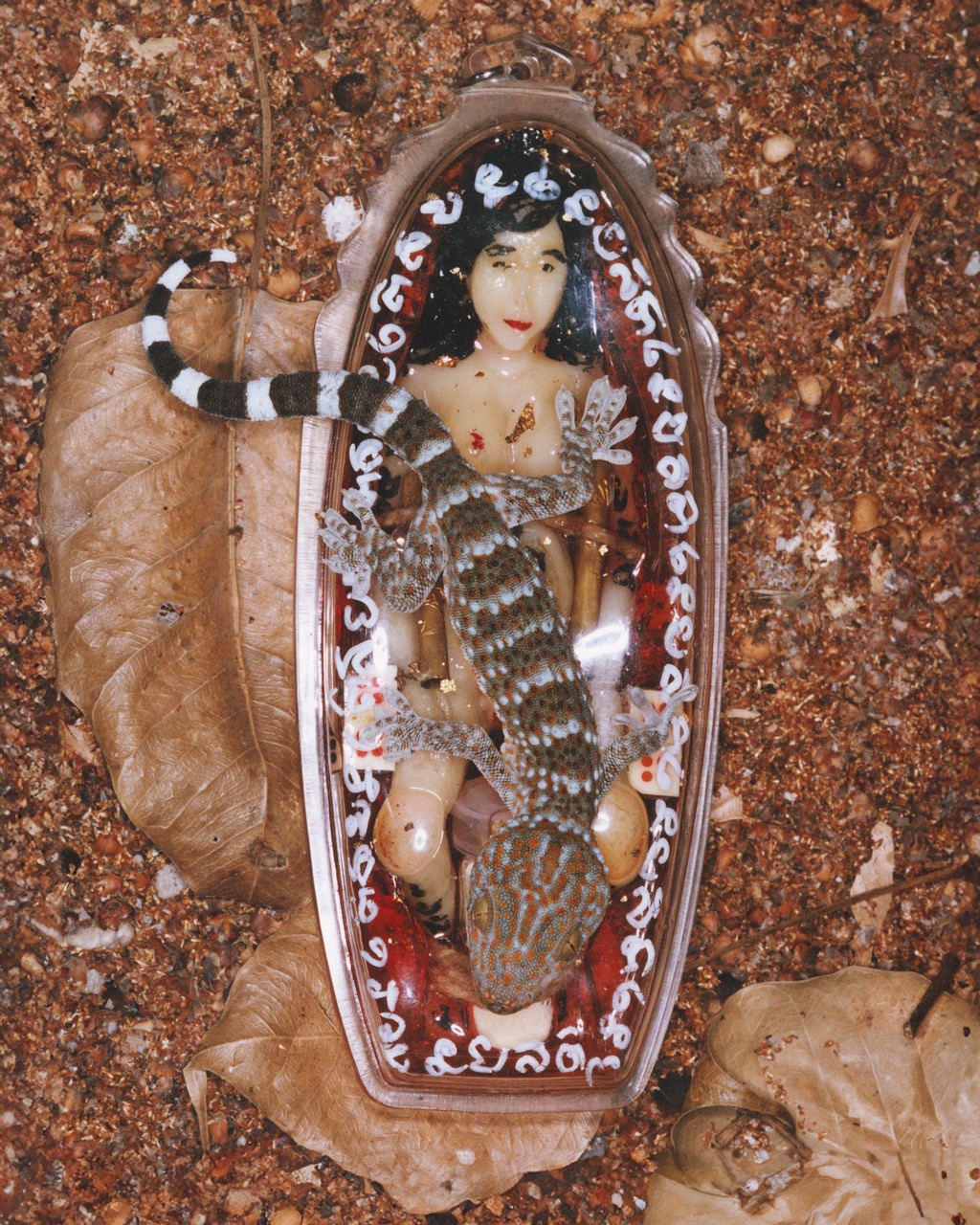

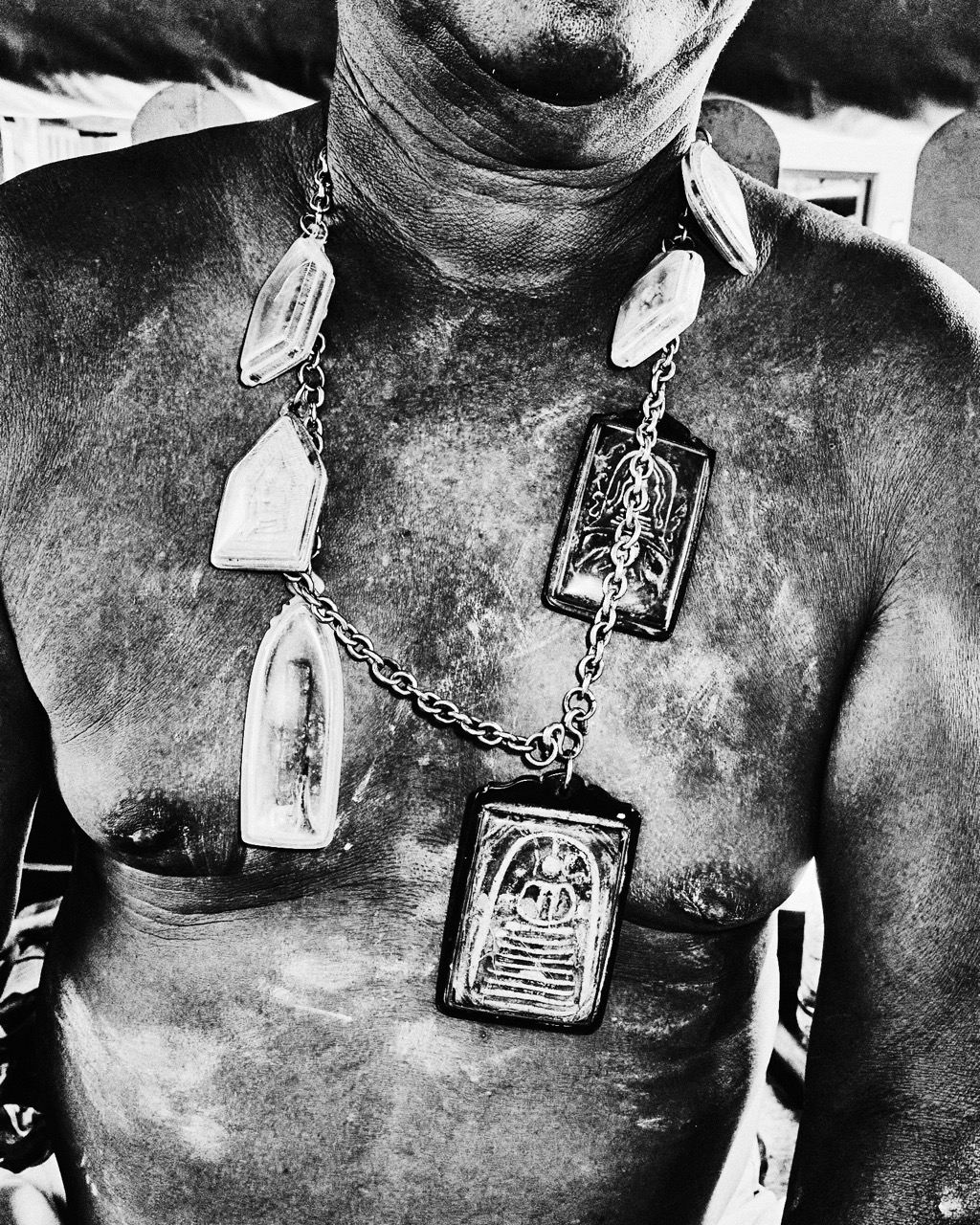

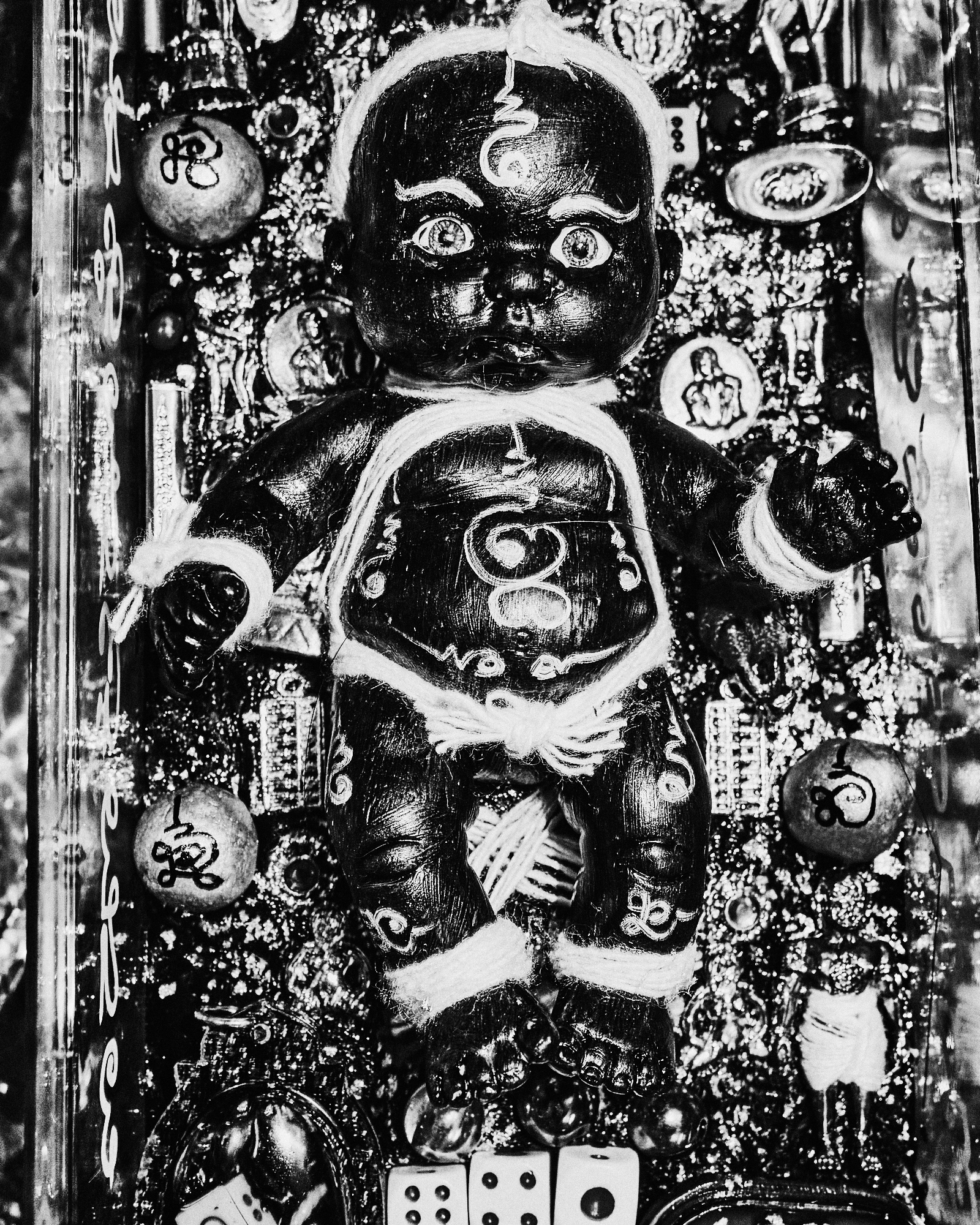

I met up with Eric at the Standard Hotel just after visiting the forensic museum and the amulet market. The forensic museum is like a beta version of the Bodies exhibit. You enter a random building in the hospital with a sign pointing to the forensic museum one way and body donation the other. They have the police report, the murder weapon, the tattoo skin used to identify the perpetrator, and the remains of the victim. At the market, I bought various amulets, filled with different oils and ingredients, blessed by an Ajarn. Some were for protection, others for good luck, fertility, and prosperity. I’m hoping to explore more of that the next time I’m in Thailand. I showed Eric some of the photos I sneaked from the museum and the amulets I purchased. Three days later, he showed up at my friend’s coffee shop with two cars full of fruits and animals (one of which was his pet giant snail). He made the outfits on the spot, molding them to the models’ bodies.

Beyond working with Eric, I also went on some side missions after getting in touch with some “herpers.” Herping is like playing real-life Pokémon. They took me to a sewer behind a train station just outside the city center, which was a hotspot for venomous snakes, drug transactions, and hookups. We met a lot of interesting characters there — people who were curious about the snakes because they knew others who had been bitten while hooking up. My herping friends were advising them on which snakes to avoid and what to tell the hospital if they got bitten.

It seems like you really became an intimate part of the community there, learning about things that aren’t visible or accessible to everyday tourists.

Yes, the zine is both a reflection of my time in Thailand and a self-portrait through the lens of Bangkok. It’s almost as if I created my own world inside Bangkok through these chance encounters.

Some of the most identifiable themes in Banana Cries are desire, sexuality, death, and decay, which seem like a continuation of your past interests.

Absolutely. In Bangkok, the same street vendor could be selling the nicest mangoes you’ve ever had, and a few hours later, they’re selling Viagra and sex toys. You could be at the forensic museum looking at a mummified body, and in the next building over, someone is being born. Banana Cries explores the bond between sexuality and mortality. It seems like these themes aren’t as taboo in Bangkok—sex and death are just part of life. Everything is right in front of you, nothing is really hidden. That’s how I feel about this project, which sets out to find connections between polarizing yet intertwined elements.

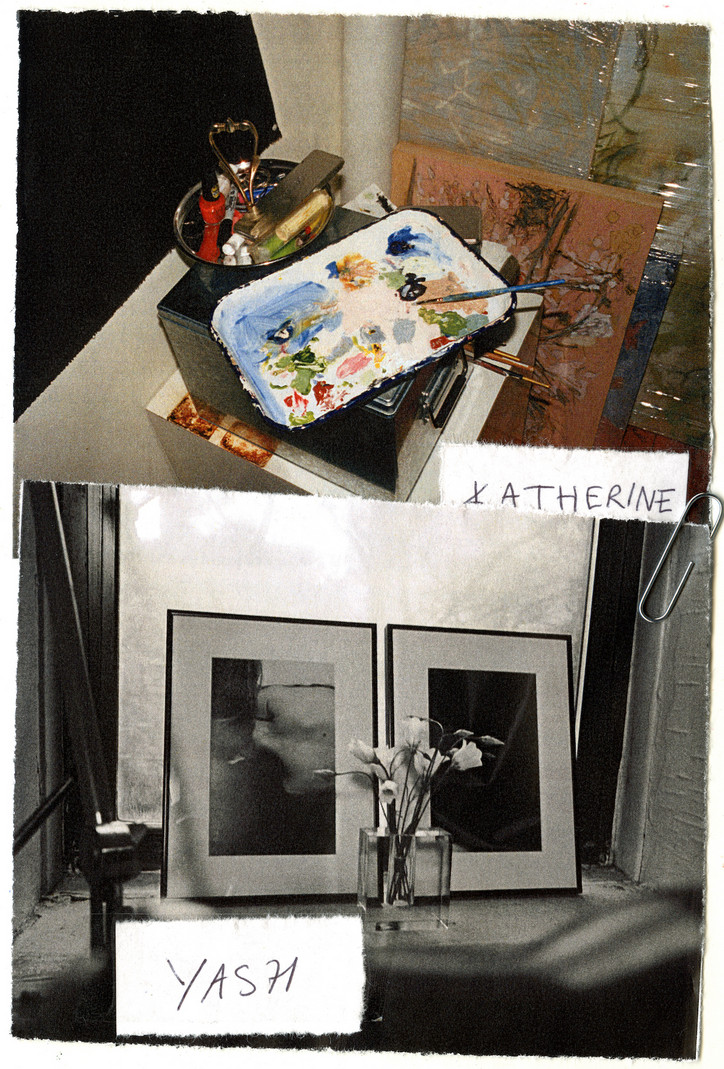

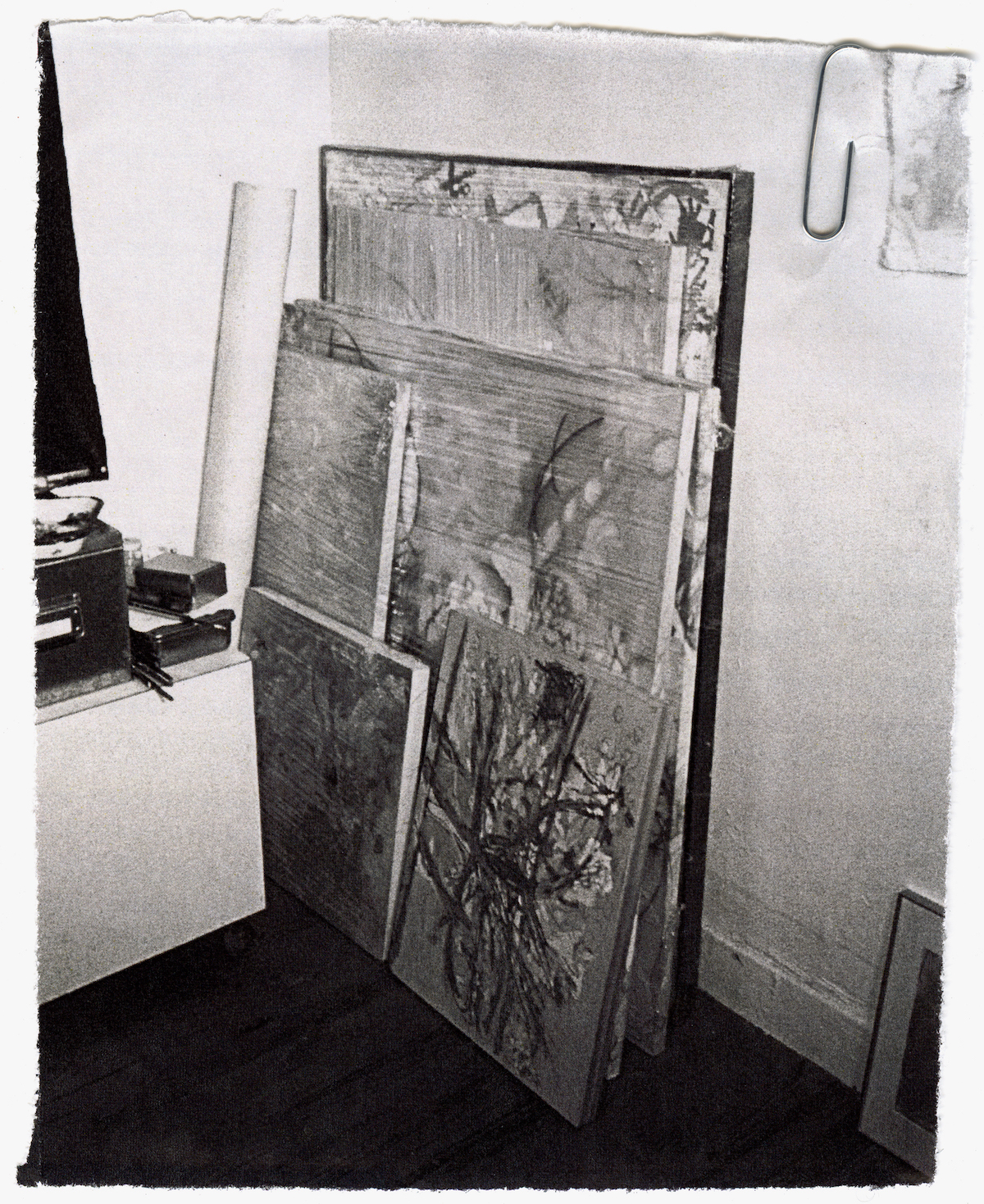

If female artists are discussed at all, they are discussed in terms of tragedy. Few are celebrated in their lifetime, and even fewer get a say in the legacy of their art. The Swedish painter and pioneer of abstraction Hilma af Klint, whose work is buried beneath the mess on their coffee table, is one example among many. But Auchterlonie and Yahshel refuse to be sidelined, selectively selling their work to buyers who they know will be able to properly preserve their work. Auchterlonie started the summer by exhibiting at the legendary Brooke Alexander Gallery on Wooster Street, whereas Yahshel began hers by turning down requests from European art fairs.

Below we speak of fake puppies, chain-smoking, love languages, sloppy kisses, desire, and of course, Hilma af Klint.

Katherine, you just moved in with Yahshel. I’m curious about what’s left behind in the old apartment.

Katherine Auchterlonie— I’m 95% here, missing the champagne glasses and some fake puppies.

Fake puppies?

KA— They’re replicas of dogs in old paintings. “Old paintings” as in the 18th century when portraits peaked amongst the privileged and their painters developed a visual language to communicate “underneath the various forms of wealth.” The artists themselves seem cool but the subjects were often uncool people. Anyhow, a sleeping dog became a symbol of infidelity. For example, you’d see a portrait of a couple on their wedding day, both very clean, very dressed up, very happy, whatever; perhaps they would have the father painted in the background, and two dogs on a leash. If one of the dogs were asleep, it signaled that the groom was cheating.

That's brilliant.

I wanted to make something out of it but it hasn’t been my vibe lately. I’m not that bizarre right now.

No sleeping dogs in this apartment. Who does the cooking, who does the cleaning?

Yahshel— I’m the chef. Kathrene leans heavier on the cleaning side if we’re being diplomatic.

KA— I wake up to the smell of her cooking.

It’s not even the sound, but the smell. She keeps quiet so as not to wake you up before the meal is done. That’s love.

KA— Cleaning is my love language.

Me sexting.

KA— But at the same time, I can’t have it too clean. I need an organized mess, especially a girly organized mess; some champagne bottle wires lying around, some old deli receipts, and… maybe a cracked eyeshadow? That’s when I’m inspired. That’s when I’m like “Okay, I know who I am today, let's get to work.” It’s an identity thing.

I was waiting for you to drop cigarette butts, too. Cooking and cleaning in all glory, but who does the cig-runs?

Y— We always pick up double packs at once.

How many cigarettes does it take to finish a painting?

KA— Oh my god. Let’s just say I’m glad my piece on Wooster [Street] is behind glass.

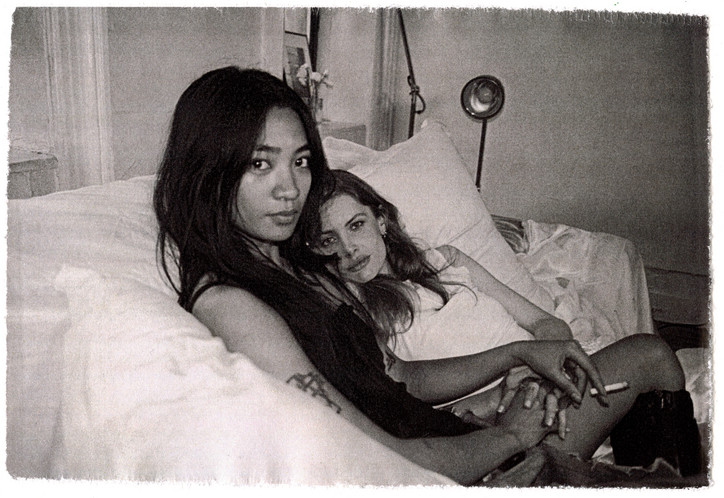

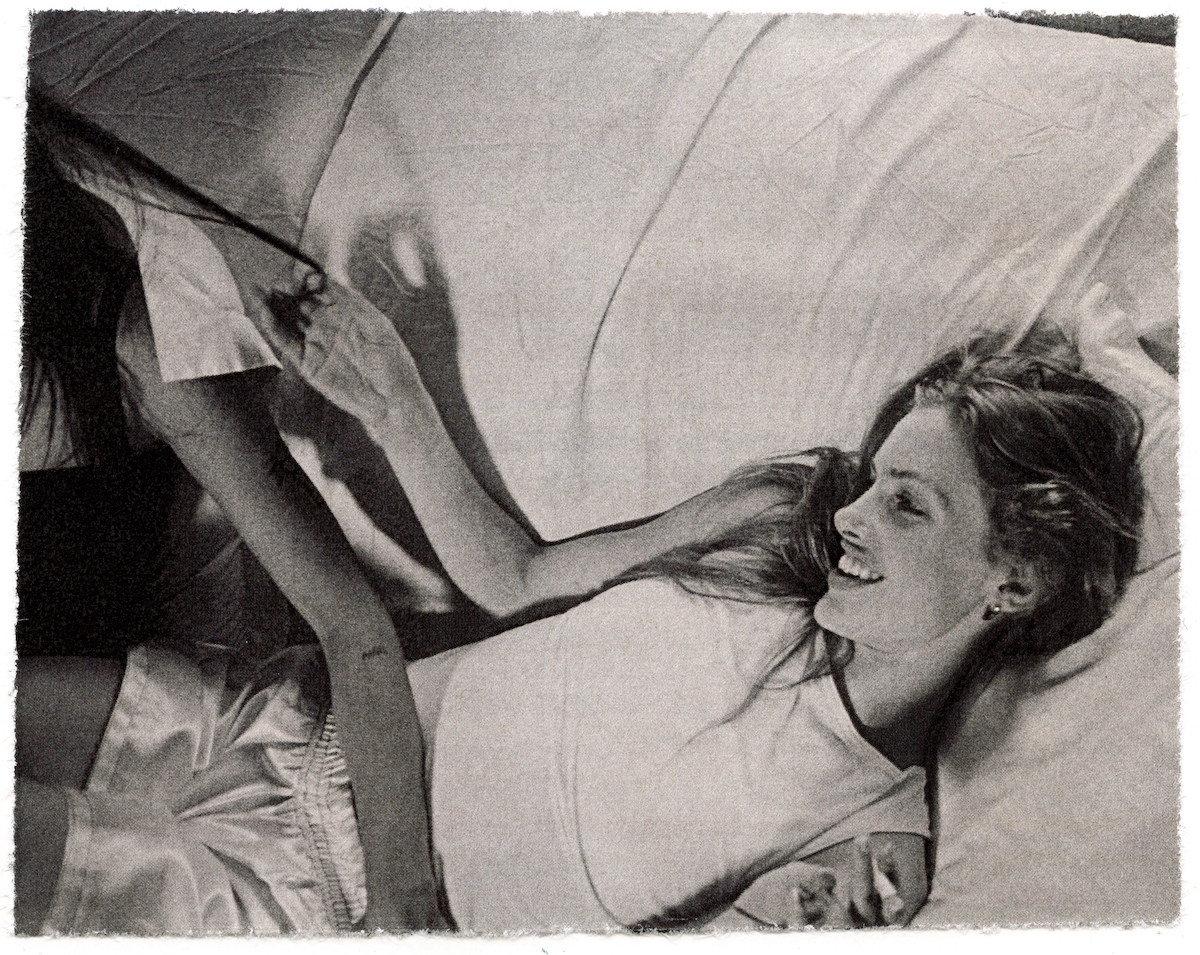

Through some of Yahshel’s photographs of you, it’s almost as if one could smell the smoke. I mean that in the most sensitive way. In your duo show at The Sitting Room [gallery], the works were displayed not only in conversation with each other but the symbiosis felt as if the works completed the other’s sentences. How much does your practice overlap?

Y— There isn’t a way that I could think of them as either dependent or separate.

KA— I mean our art is our approach to life. And Yash is a big, if not the biggest, part of mine. She influences how I feel, and how I feel naturally bleeds into what I make. It’s inevitable, maybe in the best way possible, because it allows the work to go outside and beyond myself.

All my research for my upcoming show, dating back to last April, has been centered around a notation system for diagram kissing; kissing in a way that’s not creepy or gross. The motif, however, is completely without people. I’m fundamentally against pictorial representation — it just never interested me. I almost see figurative as Islamic and why would I as an artist care about representing what God already made redundant? My practice is more abstract; I would even propose this diagram exploration as a scientific notation, which scratches an itch for me. The ultimate goal is to create an open-ended code that anybody can read and, through it, visualize an entirety of that kissing experience of their own.

In Notation of a Good Make-Out Session — your piece for Unrequited — I visualize you and Yahshel dancing around while making out, and the X’s are either where her tongue touches yours or vice versa, or perhaps that's where the heart skips a beat? Or maybe that’s me being the creep you set out to cancel.

KA— No that’s hot.

The inspiration for that piece came from the “Feuillet-Beauchamp” notation — a dance sheet commissioned by Louis XIV. The dancers read these un-abstract abstracts and followed a choreographed dance based on the drawing. Once I stumbled upon it (via internet tourism) I was like, “Okay, this is it.” So now I’m charting love in a notation system; some movements are hot, elsewhere, the kiss could read as really sloppy.

Have the two of you ever had a sloppy kiss?

Y— Do you want us to show you?

Correct me if I’m wrong but this is where the artisanal overlap takes place, in the exploration of love?

Y— Sure. I guess we started exploring the subject artistically through some [love] poems we once sent one another, which later were used both as titles and the press release for the Sitting Room. Kate’s approach to the subject matter is somewhat biological…

I mean, there’s Hilma af Klint on the table.

KA— I’d love to be compared to her. No doubt biology was my favorite class, much more inspiring than (male!) art history.

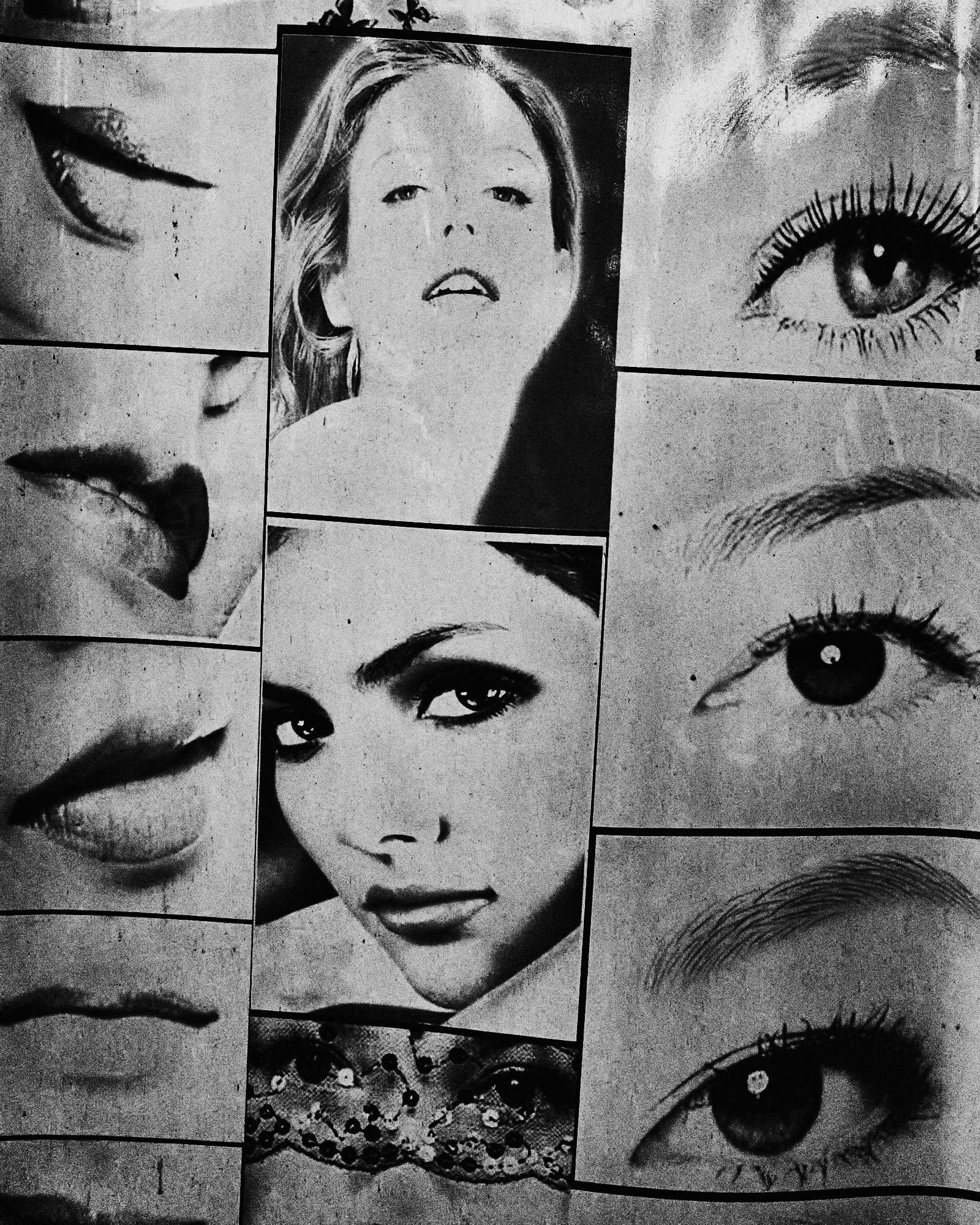

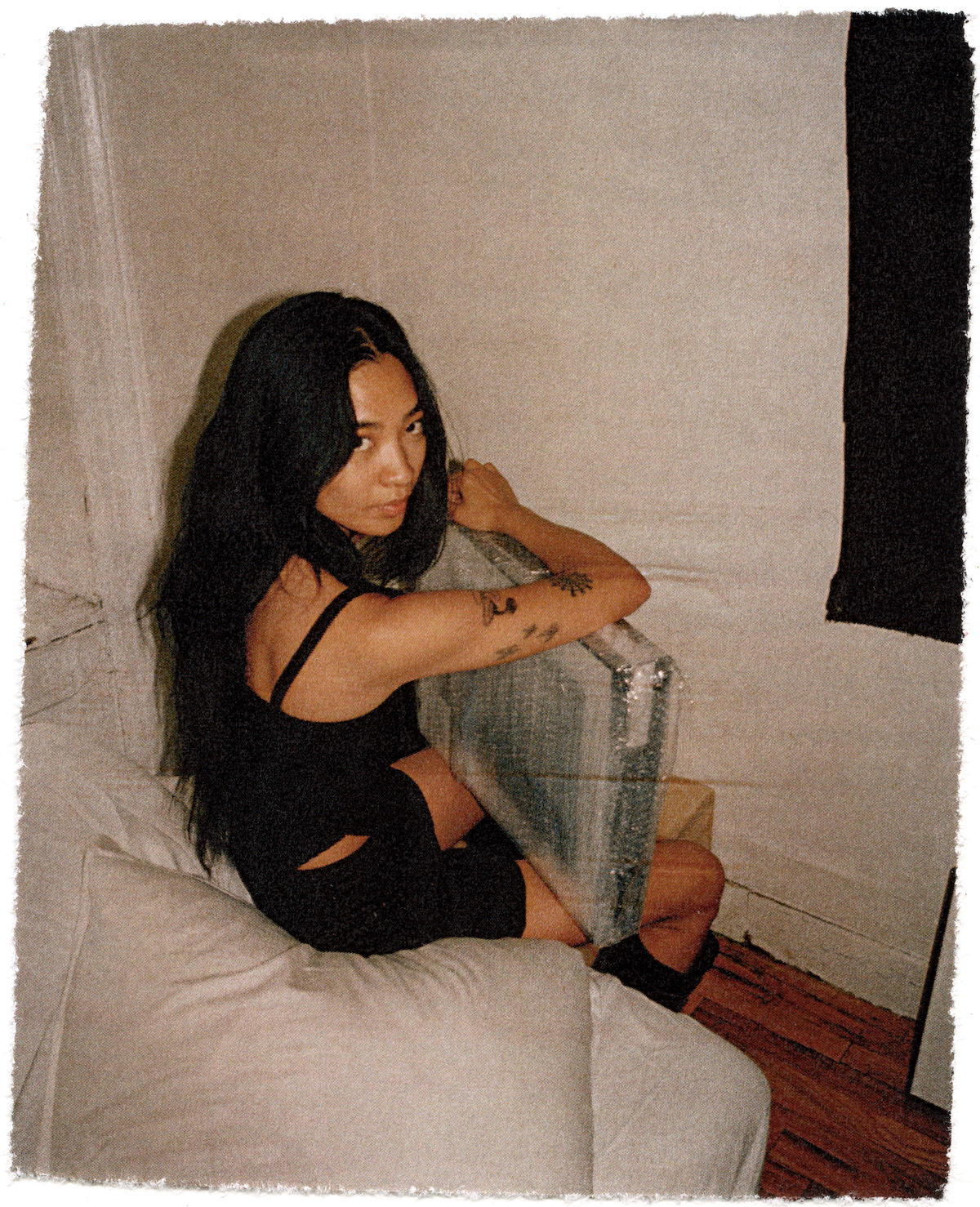

Y— Whereas my practice is exclusively photography, abstracted photography nowadays.

“Nowadays” dating back to when?

Y— I played with abstract for the last show mainly because of Katherine and how much I was exposed to her work. Before that, the majority of my photographs were straightforward portraits: friends having fun, fucking around, like any other “photographer” around here. Why I consciously didn’t tap into photography earlier wasn’t because I wasn’t curious, but being raised in the Philippines the idea of a profession has always been reserved for academics or sports. Art was never on the agenda. It took me moving to the States to realize that people are artists.

Until recently, I’ve always been “taking photos,” but Kate would roll her eyes and say, “No babe, you are a photographer.”

Your practice sits above the usual artist-muse relationship, thereby resisting falling into that objectifying false worship, and it’s brave, maybe even scary to expose something as intimate as one’s own love.

KA— The scariest part about being an artist, and a human being, regardless of what you’re portraying, is that you’re constantly hoping to be understood. Therefore, your work is somewhat contingent upon you being alive. Imagine growing up and realizing that the artists understood in their lifetime are men, whereas female artists are only later, after their passing, acknowledged as “underrated.” It scares the shit out of me. After consuming X and Y amounts of books, art history classes, and going through common art gallery conversations, was when I realized. The way people talk about women artists is tragic; they were never shown, let alone had a proper say about their art while they still were breathing. Or at the very least over 80 [years old].

Referencing af Klimt again, she’s such an accurate example.

KA— Exactly. She wasn’t an abstract artist, but google her name, go to any retrospective at any big institution, and all the labels, and websites, and auctions, will tell you exactly what she was repeatedly rebelling against. It proves that women were never appreciated for what they spoke of, but for what society was comfortable with. It doesn't help to make the work more direct. Nor do I want to. However, perhaps it inspires me to make my work physically bigger. It’s freeing to have a whole wall to paint on, almost like a cave painting. But it’s also a flex to be a small person and paint large formats. I guess that’s me saying that my dick must be bigger than yours.

What does it mean then to be self-taught?

KA— To have originality. It’s not about anything more or less than that. If you’re learning because secretly in your heart you want to look like something, or somebody else, then great, you’re a copyist and perhaps you should pursue that. You will make a shit ton of money. But then don’t come and claim this boho lifestyle. Your identity is not a painter. Saying it out loud now makes me realize how I believe it’s about intention, too. And intentions are harder to undress these days.

I’ve painted since the age of four. When the people around me started asking what I’d like to do once I get older, my response was always to be a painter. I’ve always had an answer, yet people kept asking me. Eventually, I realized that their asking was their way of saying no — if they had accepted my answer and my passion for painting, the question would have moved on a long time ago.

Y— It’s almost the same as when we run into people, and they keep asking if we’re still together. Why wouldn’t we be? We’ve also been told that it’s severely stupid of us to date each other because we could do so much better financially. It’s hidden in their phrasing, the tone of their voice, “But you’re such a pretty girl, you could be with someone who could provide you with…”

I believe that if you’ve truly ever experienced love, you would never question another person’s way of loving.

Y— Regarding your question on the scarcity of intimacy, I see the responses toward our art and relationship as validation for our work. Not because everybody votes for it but because they’re suspicious about it. It adds a dimension of social responsibility. It addresses that today, people are terrified of being vulnerable, even amongst their friends, and sometimes even around their loved ones. It’s as if we’re all set out to use the same script once we move through these interactions, and if we don’t we’re doomed. Love will always look different, but the kind of language that I hear is so damn uniform.

KA— You’ve got to have a communist mentality. My feminist theory professor would always say, that regardless if you have to make your change go beyond the span of a lifetime, eventually, your voice will be heard.

Y— That’s why archival works are so fucking important.

Making art is different from the drive to preserve your work, how do you create from that desire?

KA— It’s all the same to me. You have the drive to preserve your work because you truly believe that it is that important — because it needs to stay after you’re gone and, you know, you can’t take it with you when you die. Once you realize its value, you start aiming for galleries and private collections, then museums, because at the end of the day, you need people with air conditioning to buy your work, because that's how it stays in good shape.

Suddenly you’re no longer making art for your mother’s walls; she’s out of space, the house out of empty rooms, and eventually she will be gone. Eventually so will I. And I can’t archive my own work because death is real.

Only for humans. Original art is immortal.

Katherine Auchtomom’s Kiss Garden will be on view at Ross + Kramer Gallery until August 16th, 2024.