Teleport with John Carroll Kirby

On this album, each instrument sits distinctly apart from one another, so their tenors and harmonic contributions can be easily picked out. Wood flutes hover above round 808s; simple melodies on the piano poke through swirly sheets of retro synths. The combination is familiar and foreign. On songs such as “Blueberry Beads,” it’s as if David Axelrod scored the soundtrack to a Nintendo Gameboy game. On others, like “San Nicolas Island,” it’s as though the expressive muzak at your favorite Chinese restaurant was covered by Daft Punk.

office caught up with the composer to talk about meeting Karl Lagerfeld, third-generation exotica, and how his time with guru Sri Dharma Mittra has influenced his music.

Your last LP, a visual album Travel, featured a lot of found footage. Why'd you op for previously recorded footage instead of recording it yourself?

I was really just working with the means that we had. It was more just to have a visual component. I actually ended up doing it again down the road. On Tuscany, my piano album from last year, we did a bit of found footage.

Have you found any benefits to using found footage?

Aside from the obvious, that it's easier, it's just cool to do. Especially with my music. I'm not gonna make a music video where two attractive people meet at a party and fall in love, let's say. It's not the kind of narrative I'm creating. So in a way, it's cool to use things that already exist, because I'm not really a fan of narrative music videos. I'd rather have it where you can just listen to the music along with light, visual suggestions of something.

I read in an interview that you have a guru, Sri Dharma Mittra.

Yeah, he's actually in New York. He's a very accessible guy. But I wouldn't say he's my personal guru—it's not like I go to his house or anything. Though, he is the person I study yoga philosophy with very intensely and who I refer to in times of confusion. He's been very helpful to me and to a lot of folks throughout my life. His teacher, known as Swami Gupta, was one of the first to bring yoga to New York. That was probably, 1940s or '50s. Dharma Mittra is actually himself Brazilian, but he read a book about his guru and left everything behind in Brazil and came to New York, really never looking back. He's done a lot in New York to pass along that tradition.

How'd you find him?

I found him because I was practicing Bikram Yoga quite intensely, which has since fallen apart because of scandal. One of the gentlemen who was actually the Bikram World Champion, a guy named Jared McCann—also just a phenomenal yoga teacher in New York—he came in and saw that I was going to Bikram a lot, and he said, "Oh, this is cool, but you got to go check out Dharma. He's up in Flatiron. You got to go take his class."

Do you find that your yoga practices make their way into your music?

It does. I released an album a few years ago called Meditations in Music, and that was recorded when I felt I was at a very peaceful place, really sticking to his teachings a lot, following a calm and peaceful process throughout my day. Since moving back to LA and being away from him and his teachings, I think I've maybe fallen off a little bit, but it works its way in my music a lot. On my upcoming album, the first song, it's called "Blueberry Beads," is also inspired by him. "Blueberry Beads'' is another name for rudraksha beads, which are kind of like rosary beads for a yogi. [Mittra] is a very funny guy; he always keeps things very light. Almost at the end of every class, he says, "Hey, I'm just passing on to you what I found helpful in my life. If some of this doesn't resonate with you, no pressure." I like that approach a lot. In my music, I wouldn't want anyone to feel like I'm belaboring any point or overemphasizing any kind of spirituality.

I'd love to know more about your introduction to music. When did you start playing?

I started playing when I was 13 years old, when I started piano. I was studying with this really funny dude, a kind of neurotic Woody Allen–type dude, Roark Honeycutt. I really enjoyed those lessons. He was a great teacher, because he just made it fun. A lot of times we would go into the lesson and just talk the whole time, bugging out on stuff. On whatever. I remember there was a stain on the ceiling this one time, and I think we talked about mold. I think such a big part about being a musician is actually just being able to hangout and talk to people—it seems like you actually do that more than you play sometimes. On tour, or if you have a gig, you might play for an hour, but you'll be at the gig for five or six. After Roark, I went on to study music at the University of Southern California with a man who became my mentor. His name is John Clayton. He himself was a bass player and arranger in Count Bassie's orchestra. He was first actually a family friend, then when he saw that I was serious about music, I got to study with him.

How does your process change when you're collaborating with someone like Solange versus when you're making your own music?

When I'm collaborating, I'm always trying to think of myself as the accompanist. I'm still learning this, but sometimes all you need to do in a recording session as a keyboard player is just play the most basic and simple voicings and pads. It doesn't have to be the coolest synth sound; it doesn't have to be the coolest voicing. Sometimes that's really all that's required. When I'm collaborating, that's the primary objective. When it's myself, I get to cut loose a little bit. I still try to apply that. I still try to take the simplest approach, but at the same time, I can add more flourishes.

How'd you come to meet Solange?

We were kind of in similar circles in New York. She had been working with Chris Taylor from Grizzly Bear, and I had also been playing in Chris Taylor's side project called Can't. She had done a tune with my friend's band, Rewards. And so we would be playing at venues all around New York, and sometimes she would come in and sing the song. So I got to know her that way. But it wasn't until a fair few years later that I started working on A Seat at the Table.

How was working with her?

Great. She's great. She's really an inspired person. She has a really unorthodox approach to making music, to getting inspiration from different visuals. It's funny, she can talk about jazz, like she'll tell me all kinds of shit I didn't know about jazz, but then I'll see her talk to someone about fashion, and she'll school them on fashion, or visual arts, or movies too. She's really a knowledgeable person, and she would draw on that stuff a lot. She's also very free.

Can you tell me a little bit about when you met Karl Lagerfeld?

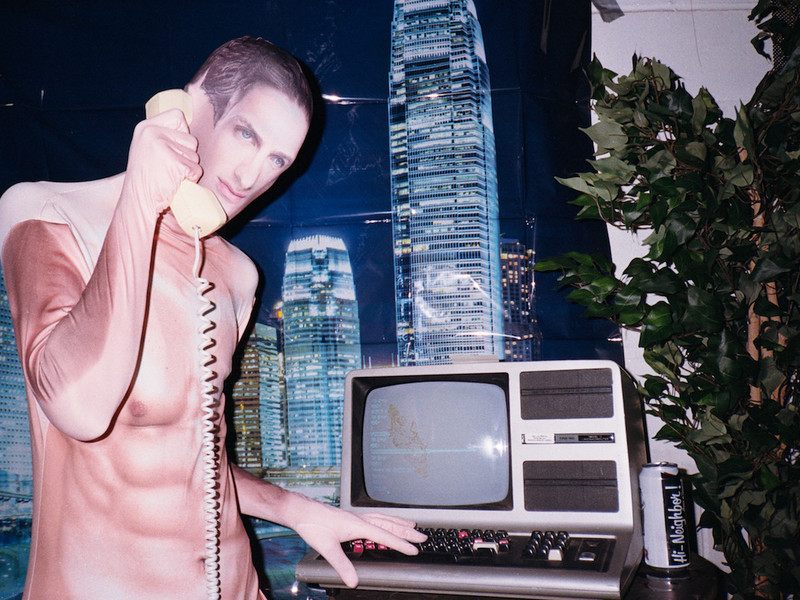

I was working with my good friends, Sebastien Tellier and Dan Stricker; we have a band called Mind Gamers and also an LP coming out sometime soon. So, Sebastian had been doing music for the Chanel shows, and he had toyed with the idea of asking Karl to do something for it. He was a little nervous but decided fuck it, the worst he could say is no. He asked him, "Would you maybe want to read this little poem at the top of the song?" The song is called "Golden Boy." And Karl's right hand, a woman by the name of Virginie, got right back and said, "Yup. Come in tonight. Karl shows up to work at 8 p.m. Come in at 7 p.m." We were all so excited. We went immediately to the bar to have champagne to pre-celebrate and ease our nerves. Because Karl is the kind of guy who commands a lot of respect, we didn't want to be too nervous. So we came in with this little intro to the song, and we said, "Karl, we want you to read this." And he looked it over and goes, "Who wrote this?" I raised my hand, and he said [in his best German accent], "It's güd." From then on, I thought, "We're cool. He's happy to be doing this. I can tell." He then told us, "I will do this in Sprechgesang." And we were like, "What is that?" He told us, "It's this 20th-century technique employed by the likes of Arnold Schoenberg." And so he reads it perfectly, and his whole team, all his assistants in the room, start clapping, saying, "Brilliant, Karl. It was brilliant." And it was really true. It was great. He nailed it.

It seems to me that you have a pretty solid grasp of music theory and history, so given that, how would you describe your music?

I think a big part of my music is imagination. You know someone just told me recently, "I feel like I'm in a surrealist painting—but a very simple one. Not like a Dali, where the clocks are melting, but there might just be a statue in the distance, or a mountain, or a coyote." I try to create a space when I make music that you can sit in, a mood. I'm actually very inspired by a Larry Hurd album called Sceneries Not Songs. I find that's a cool way of putting it. For Travel, I was very inspired by the genre exotica, because it tries to elicit a certain vision using sounds that you're already familiar with. So if you're making music about Polynesia, let's say, you would use sounds from the regular, European orchestra, but while trying to make people feel like they are in a certain location. And I thought that was a cool technique—to use your imagination with sounds you might already know.

You've mentioned before that your music is "third-generation exotica."

Yeah. So the first generation would be something like Les Baxter. And then a few years later, Haruomi Hosono's Yellow Magic Orchestra sort of reproached exotica with their own view, using synthesizers instead of orchestral instruments. My third-generation exotica uses synthesizers, uses real instruments, but also samples—things downloaded off the internet or played in contact. But the mindset is still the same, the goal is still the same.

Why the fascination with non-western themes?

Well, my upcoming album My Garden is really more focused on LA, and my previous album Tuscany was really focused on Italy. But I just find it really peaceful. I've been attracted to a lot of eastern ideology. I find that it resonates with a lot of people. When I was living in New York, studying yoga was a really great way to balance the chaos of the city. I've just found it to be very helpful in my life. It's certainly a personal connection. I've always been attracted to mythology, and I've found that the stories in a lot of eastern cultures are very rich and have a lot of meaning.

So if My Garden is focused on LA, what specifically did you want to focus on?

As opposed to my other works, which have been thinking about things far away, for this one I wanted to bring it home and talk about stories, locations, and feelings that are meaningful to me. Like I have a song about Arroyo Seco, which is the natural area near my house where I grew up. I also have a song called "San Nicolas Island," which is about an indigenous woman who was left on an island for 30 years of her life, all by herself, just off the coast of Santa Barbara. Her name is Juana Maria, and she's known as the Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island. Missionaries came to the island, captured her tribe, the Nicoleño tribe, and brought back everyone to Santa Barbra except her. It wasn't until thirty years later that they found her still living there. They ended up taking her to Santa Barbra, but she didn't live long. I think she died of smallpox, or something very common. It's a sad story but inspiring too that she was able to survive like that on her own.