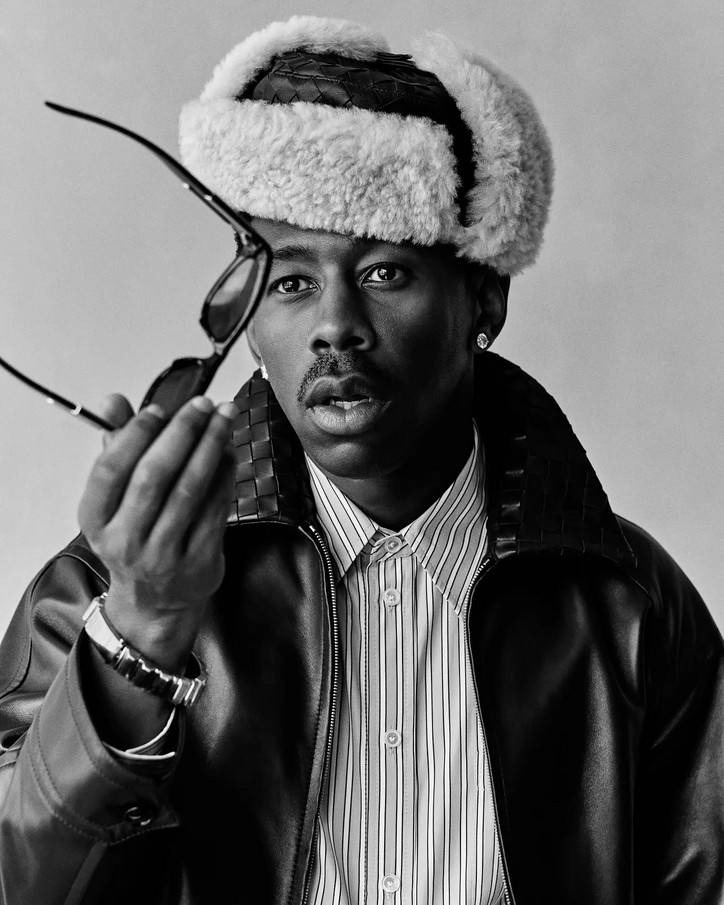

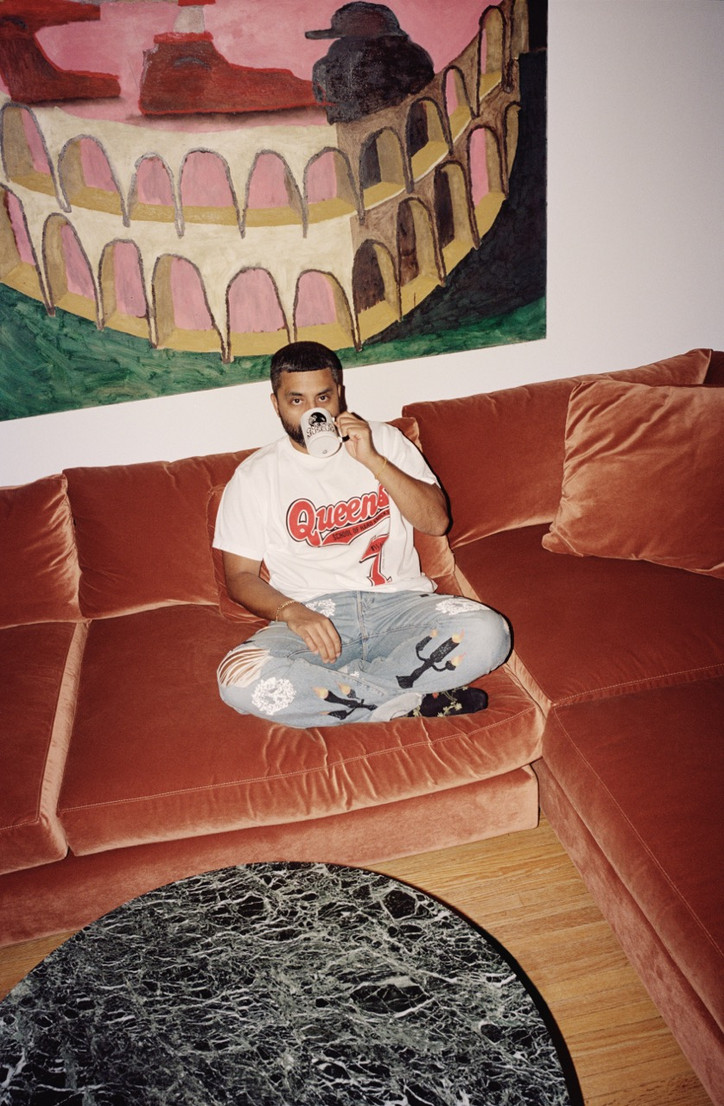

That Is The Tempo: Angelo Baque

KUNLE MARTINS —When did we first meet?

ANGELO BAQUE— Well, I’d like to hear your version of how we first met - or when we first met. KM – Let’s do it like The Dating Game, with versions. For mine, I don’t really know, but I would assume it has something to do with graffiti writers wearing North Face somewhere on Broadway, somewhere between 8th Street and Houston. Either walking up or down, right in between that zone. Catching tags, maybe on McDonald’s, or The Wiz, or just standing around. Probably had some kind of Teddy Bear polo thing on....Who were you? You were friends with TCK people.

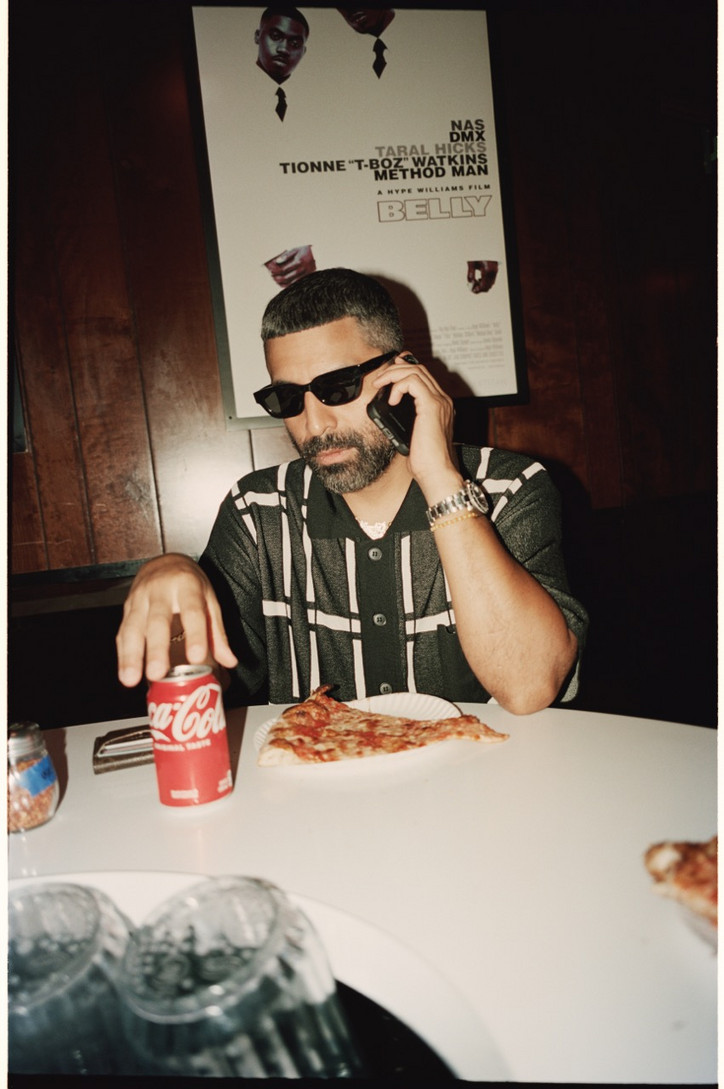

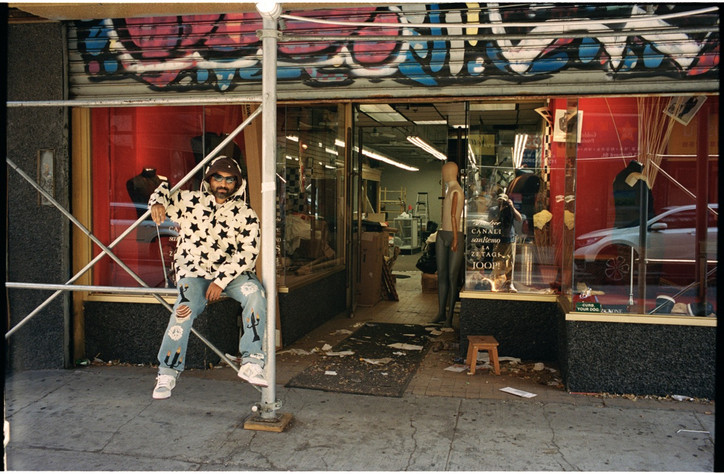

AB — I remember you because I worked at Canal Jean Company in ‘96, and I started seeing EARSNOT tags around the store. You know, a lot of people don’t know, but Canal Jean Company was a graffiti writer hub for boosting and for employment. I remember we were walking by the Cube, and Dove’s like, “That’s EARSNOT right over there.” Because we already had seen you on all the back streets. I think when you had just gotten that fire escape on Crosby, and you did the straight letter fill in, so I was just like, "Oh, this kid's getting up.” I remember you had big UFO pants, and—

KM— That I probably got at Canal Jeans.

AB— Probably. Mad skinny. Yeah. I remember that was the first time I met you.

KM— Happy. Right?

AB — So happy. Just really like, "What's up!"

KM— I just met Wombat the other day at [Public Access]. Reminded me of myself when I was happy, super new.

AB— Optimistic.

KM— Not tainted by any graffiti drums. You can do that now. You can write graffiti and not attend any graffiti functions, not have any graffiti circles, just be on your own. That was my thing. But I wanted so bad to be in. I quickly got ruined. Wow. So you wereworking at Canal Jean – that’s the end of an era. Were you around for Unique? Did you ever see that?

AB— Yeah. My sister's six years older than me, and we’re a very immigrant family. Wherever my sister went, I had to be there. I remember the first time going to Unique and seeing the airbrush station.

KM— I would imagine it was like the Alife of its time.

AB— It was just so bugged out, and the people that worked at Canal Jean Company in the basement were weird — that’s where they put all the weirdos. Unique was just full of weirdos. Everybody that worked there, I remember was a fucking weirdo.

KM— It sounds like a Netflic series, where they do a history of people who are now something else, like that Wu-Tang show. Just the version about people working at Supreme, or working at Alife, like, "Oh these are your graffiti heroes." So, when did you start Absurd?

AB— Absurd started in 2001, when I was working at Stussy. I had done my first freelance graphic for Jeff Staple. I did two tees, and I think I got pennies on the dollar — nothing against Jeff, that's what you got paid for graphics. I was just like, I think I could do this on my own." I went to Rich at Pro Graphics for my first run of t-shirts. I remember being stressed out having ten grand in cash on me, traveling on the train with that and having to bring the cash to Rich and do the thing, you know? Now I feel like people hold money in the streets like it’s nothing.

KM – It was your whole life. Ten grand meant everything. Plus, life was more hectic back then. Things could happen. And you had less experience making those connections happen, right? Plus, Rich is also a pseudo-Sopranos character, and will kind of make whatever he wants for you. I remember my second wave of IRAK t-shirts and hoodies. Well, the first hoodies and first long sleeves — the black long sleeves and the gray hoodies. Those were supposed to be black hoodies, and Rich was like, "We'll just do this. It's fine." I was like, "But that's not what I paid for," and he's like, "You're good." I was complaining to Rob [Cristofaro], co-founder of Alife, like, "Yo, what is up with your man?" And he's like, "That's Rich." It was almost like theme music played in the background when he said it. Pro Graphics was really good and professional, but Rich, I guess he had the market cornered or something. I mean, there were other options in New York, but he was doing stuff for Supreme.

AB – He had all the big boys at the time. So it was kind of a rite of passage to work with Rich.

KM – A lot of people came out of the Supreme and Alife umbrella who were making clothes. So there was probably a minute where he was fucking bubbling, kicking out all the little homies that wanted to do all-over prints. But Absurd was dope. I loved my EPMD Absurd sweatshirt. And then after Absurd, I feel like there was something else before Awake…?

AB – Nom de Guerre. I was there for a while.

KM – Wow. That’s another umbrella, Nom de Guerre. It was highbrow. It was a little erudite, and nose-in-the-air, Miss Me with all that lowbrow shit. Kind of like, “We don't care. We're definitely trying to not attract a certain kind of customer. We're aware that people aren't going to get it, and that's okay.” Design-wise, it was just daintier, just nicer, and the clothes were cut and sewn, right?

AB – Yes, most of the time. And it did well. I just think, like all great, amazing things, it was just ahead of its time. So, all the things that you say, it's funny. Some of it is true, and I wish it was that considerate. I'll only speak from my part, but being on the inside, the concern we had was, "How are we going to make money?" We went the complete opposite of what everybody else was doing downtown. Because remember, that was the height of the retail mafia. Alife, a NY thing, Supreme. It really felt like us versus everybody. It was like the old guard, and there was a handful of people that were really nice to us — and that's you. You were part of that crew that was very embracing of us.

KM – I mean, because you guys were cool. You're all friends. It wasn't like you were the lacrosse bros, or whatever, because that would've been different.

AB – And I don't think the intention was ever to be elitist.

KM – No, no, not at all. It was insane. There was no blanks. It was cut and sewn. It was more expensive. It was a whole thing. And then from there, wow. It's just so interesting to see what everybody's been doing this whole time, so much going on… So you're 44. It's 2022. How long have you been doing Awake?

AB – Six years, officially, since leaving Supreme. There was two years overlapping that it was more of a fun thing, which I don't count those first two years, because my priority was Supreme. But then in 2016, it was time to hit the road.

KM – Guys were like, "What are you doing? You have a fucking dope job. Why would you [do] Awake? It was cool, but I don't know if there's a future here, Angelo.”

AB – That was everyone that I told. No one really understood. Because right when I was working there, that's when the LV collaboration dropped. So it was the height, height, height.

KM – Also, people were psyched. Well, I'll speak for myself, I was psyched to see you there. Charles was working in the store. You were in the office. Finally my friends had positions of influence, and power, and value. And then you started doing Awake. It's always hard to leave, right? Can you [talk] about that — leaving something that's a sure thing, paycheck every week, insurance. And it was probably a job that you enjoyed, contributing to culture. A lot of people have a job. They get paid every week. They hate it. Can't stand it. And it's like they got nowhere to go, got a lot to lose if they leave that job.

AB – People that don't know the ins and outs just see the perspective. You can't put a price on freedom. That's what it boils down to, you know? My stress – I always say this to young kids or whoever I'm talking to – my stress today is my stress. It's not transfer stress from a corporation or an individual. This is my shit today. And to be honest, I'm stressed right now about this, you know? But I'll tell you one of the greatest benefits that I had working there was the ability to help support people in those 10 years. To help people jumpstart their careers, or restart their careers, or put some money in people's pockets. That shit was dope.

KM – So, what was your first collab that you did with Awake? Because you got that pretty popping, right? You got shoes, you got coats, you got stuff going on. You got a full line.

AB – I think the one that got us our respect was our first Asics collab. When we dropped those green and silver Kayano 360s, people were really into that, and I felt the shift. Because it wasn’t just another brand making logos. Remember that six years ago, everybody made a logo hat. Logo hat, logo tee, Instagram sweatshirt. That's kind of, what is it? The playbook or whatever. And nobody had really graduated into making cut-and-sew, or doing sneakers or whatever.

KM – You did that at a perfect time, where people wanted something else. They were ready for something else, and it was refreshing. Asics was refreshing, Awake was refreshing. And there were plenty of people with money that wanted that, and you saw it and you stepped right in, left Supreme to do your own thing. Really inspirational. It's really hard to do that shit.

AB – You're doing it yourself right now, too. Our paths have always been kind of intertwined, but both of our trajectories – you reintroducing IRAK and the inception of Awake – has a lot to do with Virgil.

KM – I am.

AB – It was serendipitous. Right when I left, Virgil started wearing the Awake hat, and shit just cracked off for me. And I saw the same thing happen with you, him rocking the IRAK hat, it felt like right as you were like, "All right, I'm going to do this on my own." The Adidas shoe cracked off, the hat cracked off. For a minute, I saw everybody rocking the hoodies. It was just like, "Oh, this is dope. Here we go. It's 2003 all over again."

KM –And I actually didn't want it to work out because I was doing art stuff. I was like, "Here, I'll make some t-shirts to go with the hat, with the sneakers, and then leave me alone." Because this never works out. This clothing shit never works out, or it hasn't in the past. It's always a bad relationship. But things just worked out. Virgil had a big part in that, too. Being in the right place at the right time, being of sober mind. Because I tell you, smoking up all my profits and snorting them all up was not good for business. But it had to happen. That was the whole point of me doing it, just to party. It was a clothing brand to fund parties, partying purposes.

AB – That's what happened with Absurd. I was at MAX FISH.

KM – I needed money to buy drinks and drugs. Not even to pay rent, it was so weird. And now this time around, it's completely the opposite. It's like, "Oh, who do I know that makes art that's been creating stuff that I can put on for this collab?" It's not even about me. It's about other people. It takes a lot of the stress off. So, this is a question I've been avoiding the whole time: why not just keep your shit online, bro? It's 2022.

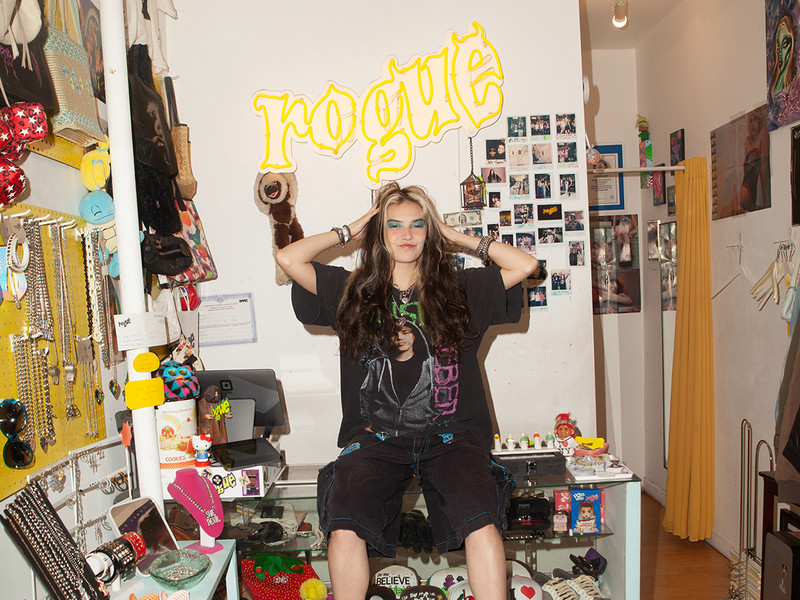

AB – There's a few answers to that one question. The first one is, for my humble opinion, for the brand to be taken seriously, we need a physical space. It's time to graduate off Instagram. Two, part of the reason why I continue to do Awake is it makes the 18-year-old me happy, the kid that you met at the Cube, the one that carried silver click clacks, and fucking stole with Bonafide, and hung out with TCK. You know, my graffiti crew. That kid needs a space to hang out today. That space doesn't exist below 14th street. With all due respect to all the other businesses that exist — there's no place where the fucking outlier, native New Yorker kid that can just come, the shitty kid that hates his parents and needs a place to hang out. You talk about Unique, Canal Jean Company. You’ll remember when we met at the Awake store in 2022, and now we're working on this project together. It was all inspired by us chilling.

KM – That's what I'm saying. I love that connection. This goes back as far as I can remember. Who was inspiring, who that inspired, who inspired me. This is the epic story, you know? And it's still going. And not everybody makes it to the end.

AB – No. We're literally survivors of the early 2000s. The herd thinned. We met in the mid-'90s. A lot of people don't talk about the 2000s, as if it's not fucking 20-something years ago at this point. We were all kids running around in these very streets. Ludlow, Orchard, Rivington, Stanton, fucking copping, and shooting, and snorting, smoking. And here we are, starting our own businesses. You can't make this shit up.

KM – I shouldn’t be here.

AB – The title of all our books, you know what I mean?

KM – What do you do? What's left after all that? What's left is the memories of all the good stuff, what inspired you. This is you trying to take 10,000 to Rich again. It's like, "Yo what, how do you do this?" Supreme is in mad stores. Alife opened mad stores, or did that at mad times. You've never done this before. This is exciting. This is my peer. Again, this is someone I grew up with in New York doing something.

AB – Who's to say that there isn't going to be an IRAK store across the street next year? You know what I'm saying? Or Pot, or Barriers, or all these new brands that are popping up too, that obviously are taking notes from our books. I want to at least be at the forefront of newness. There's dope shit around here, too. You know what I'm saying? Bode's store is right down the block, Scarr's Pizza, Dimes. But there's nothing like this — with our history, our legacy.

KM – New York shit. This is some real New York. This is a New York story. It just makes me feel good. Because I mean, it’s all passing the Olympic torch. You know, you're a worthy runner.