Think Giggle

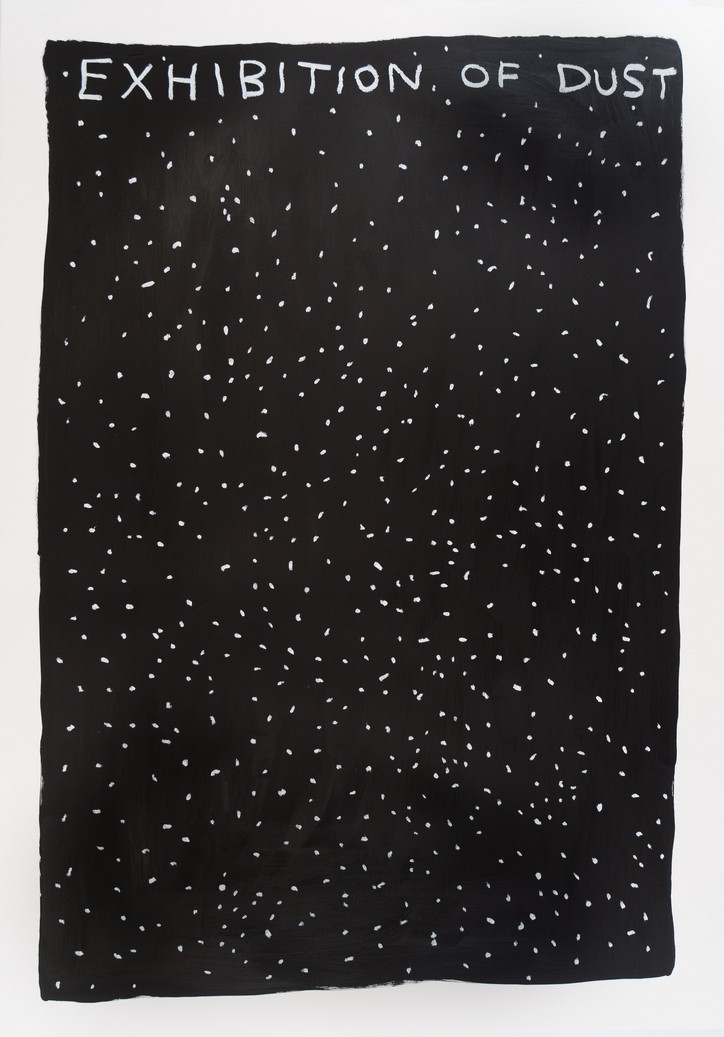

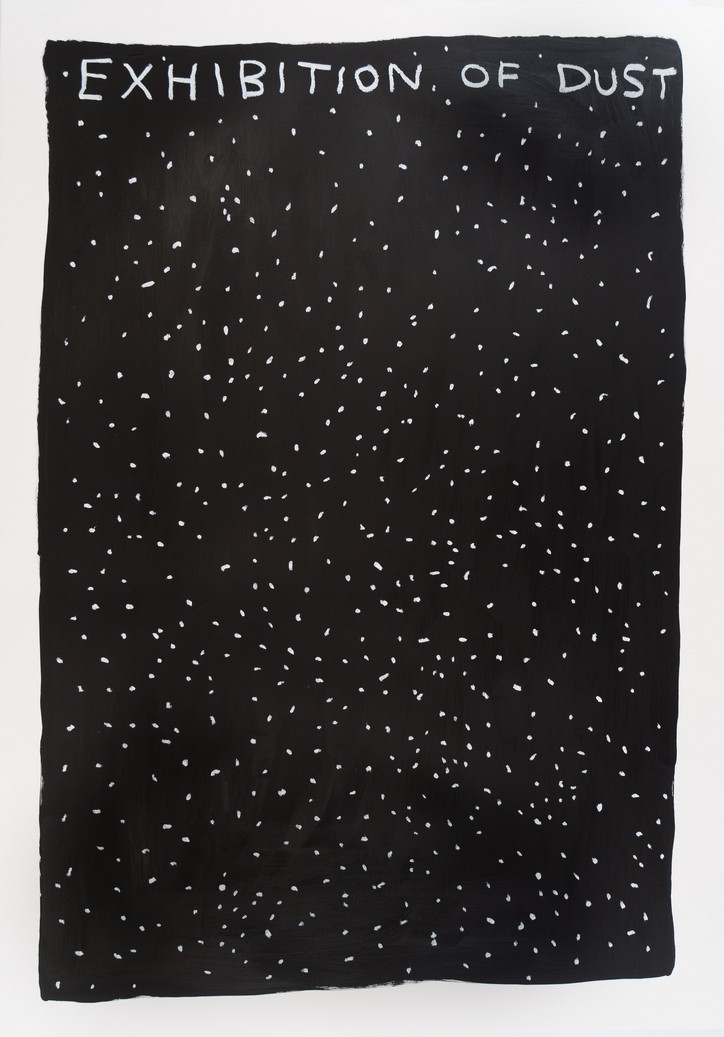

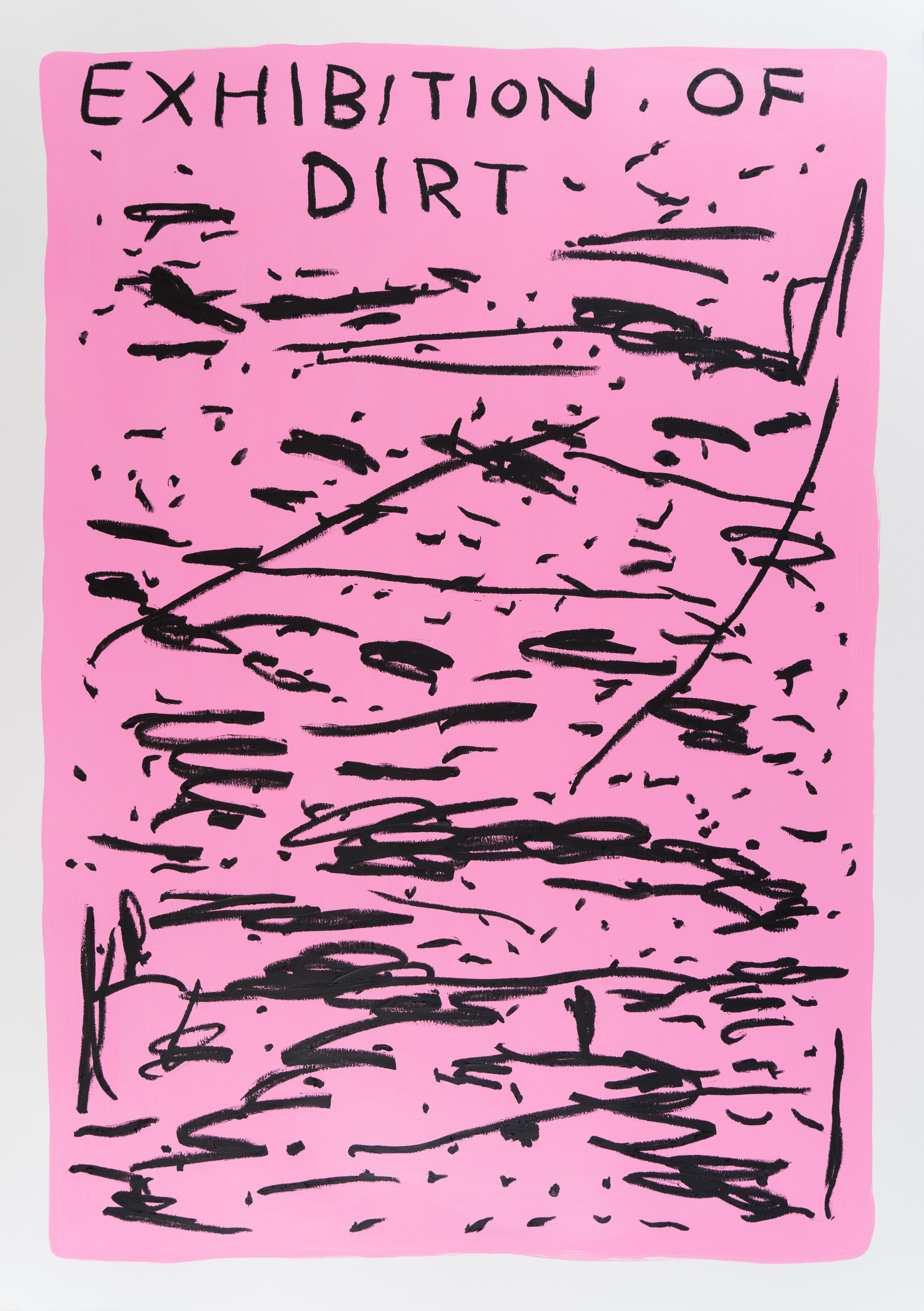

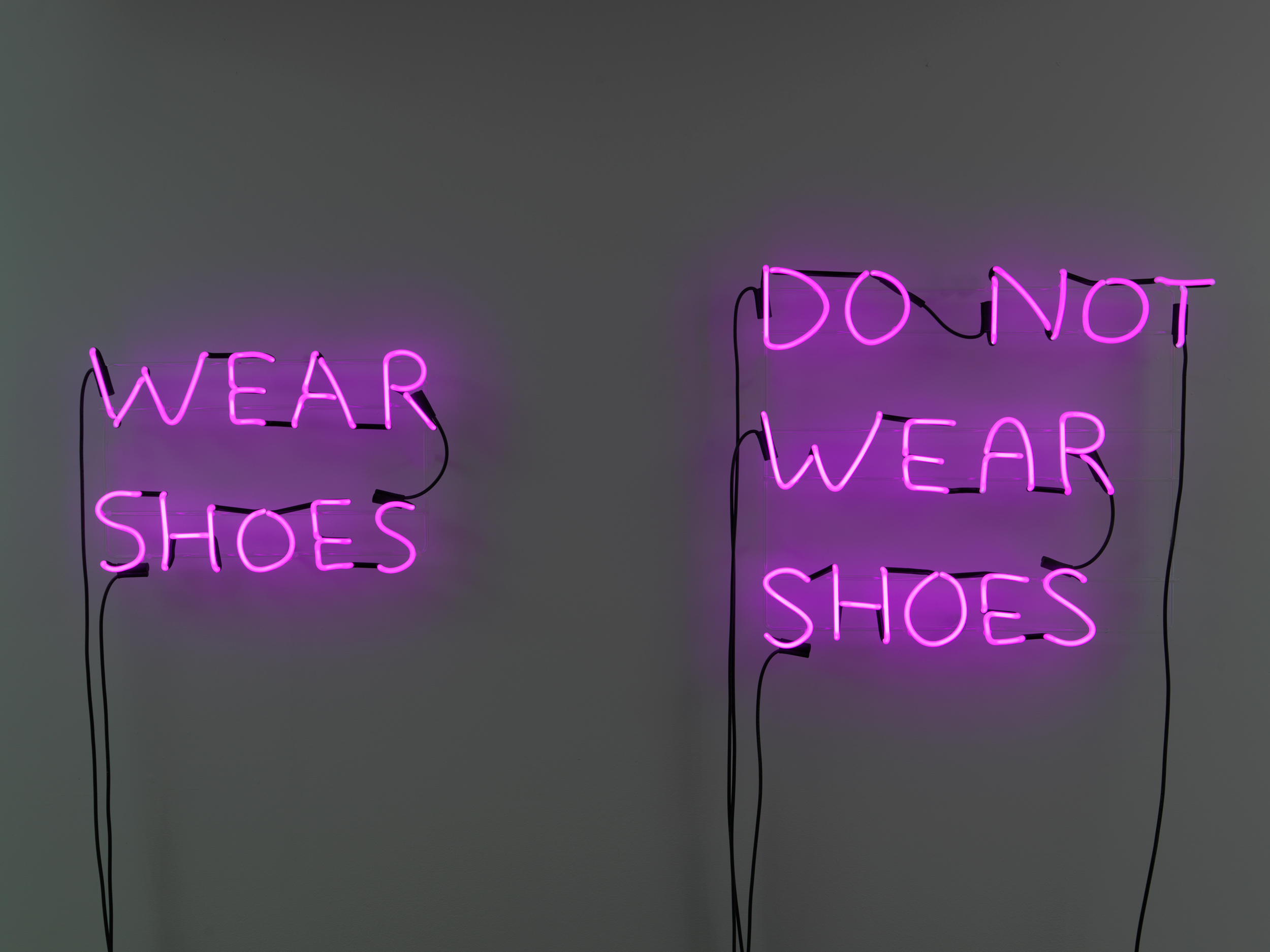

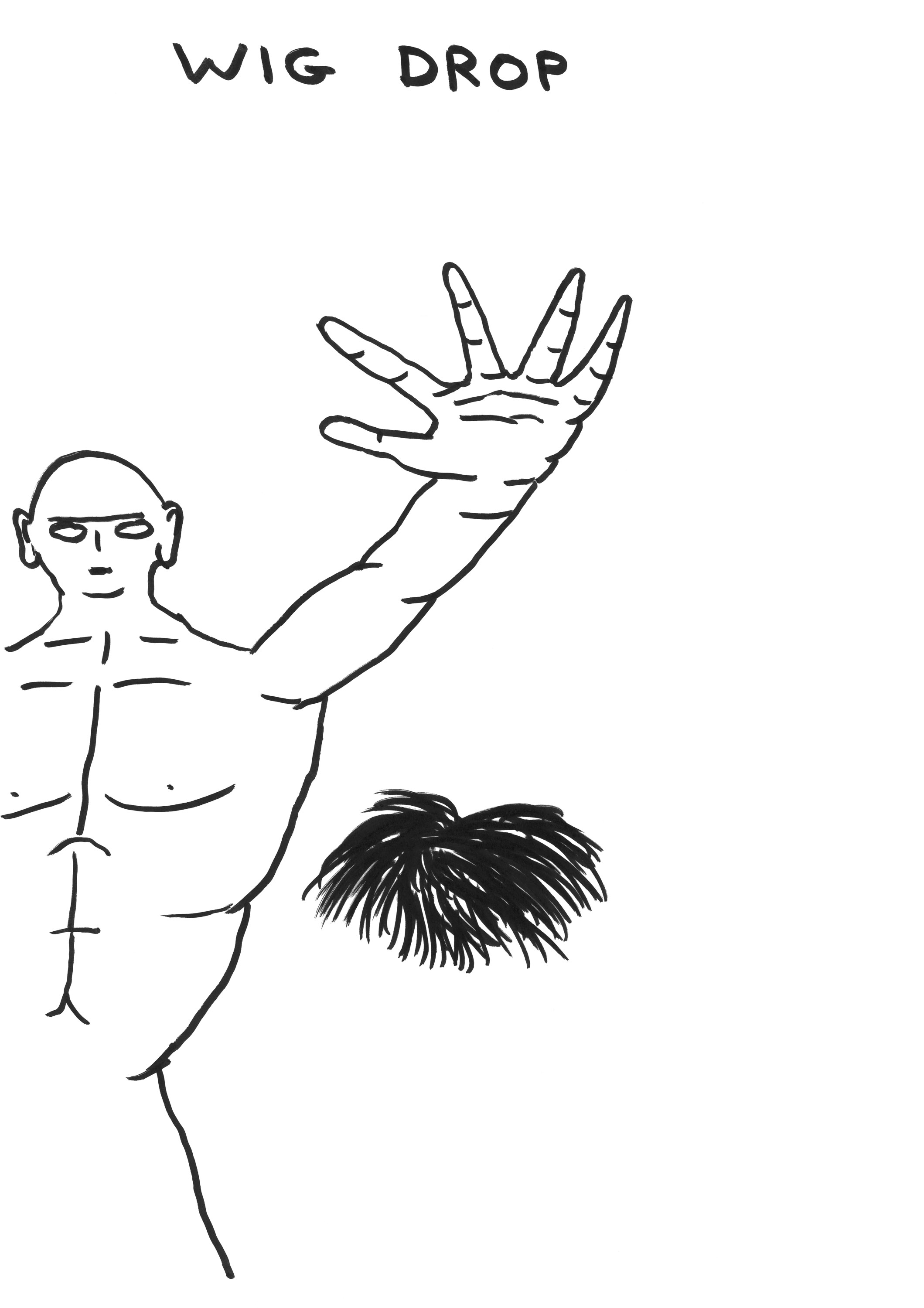

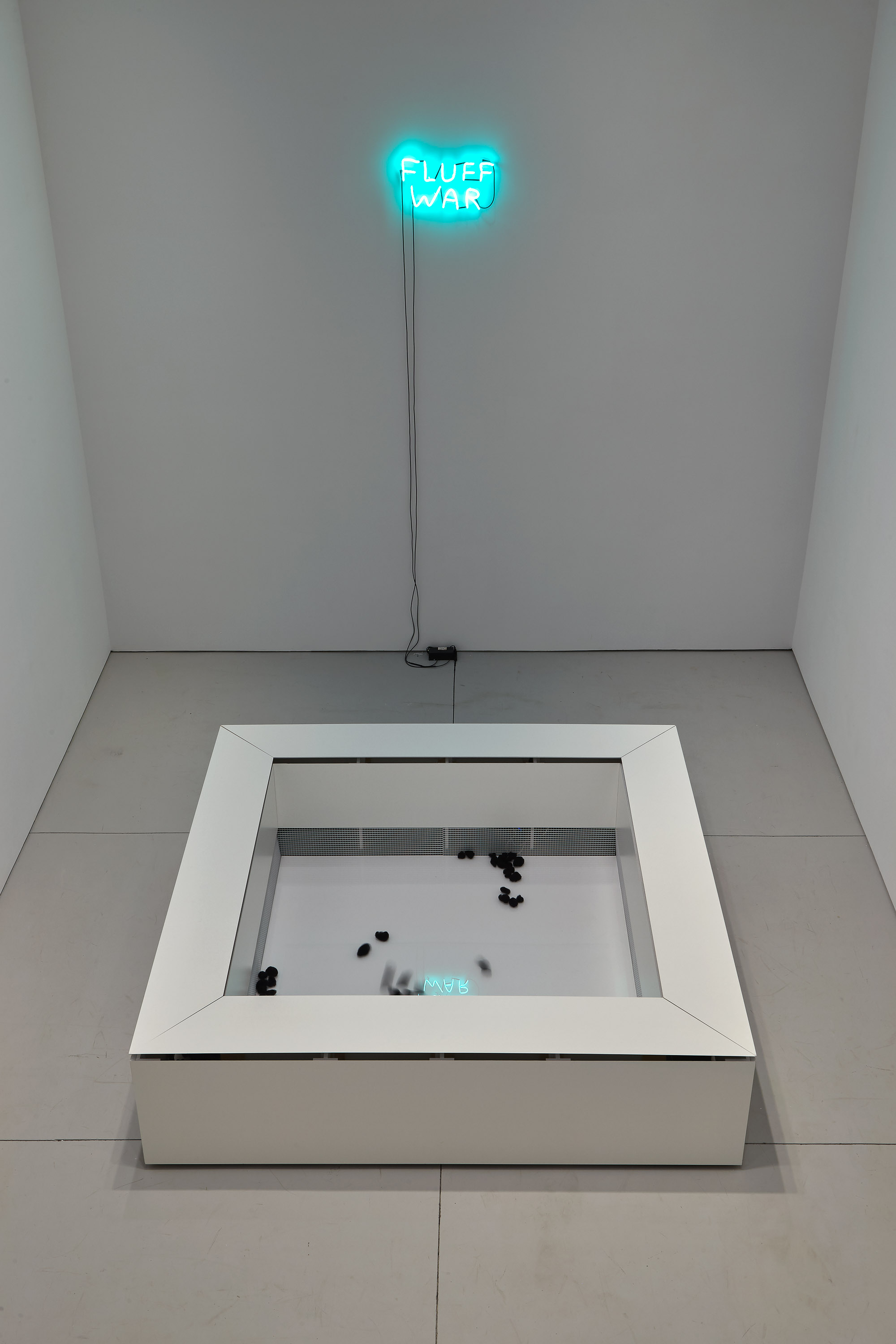

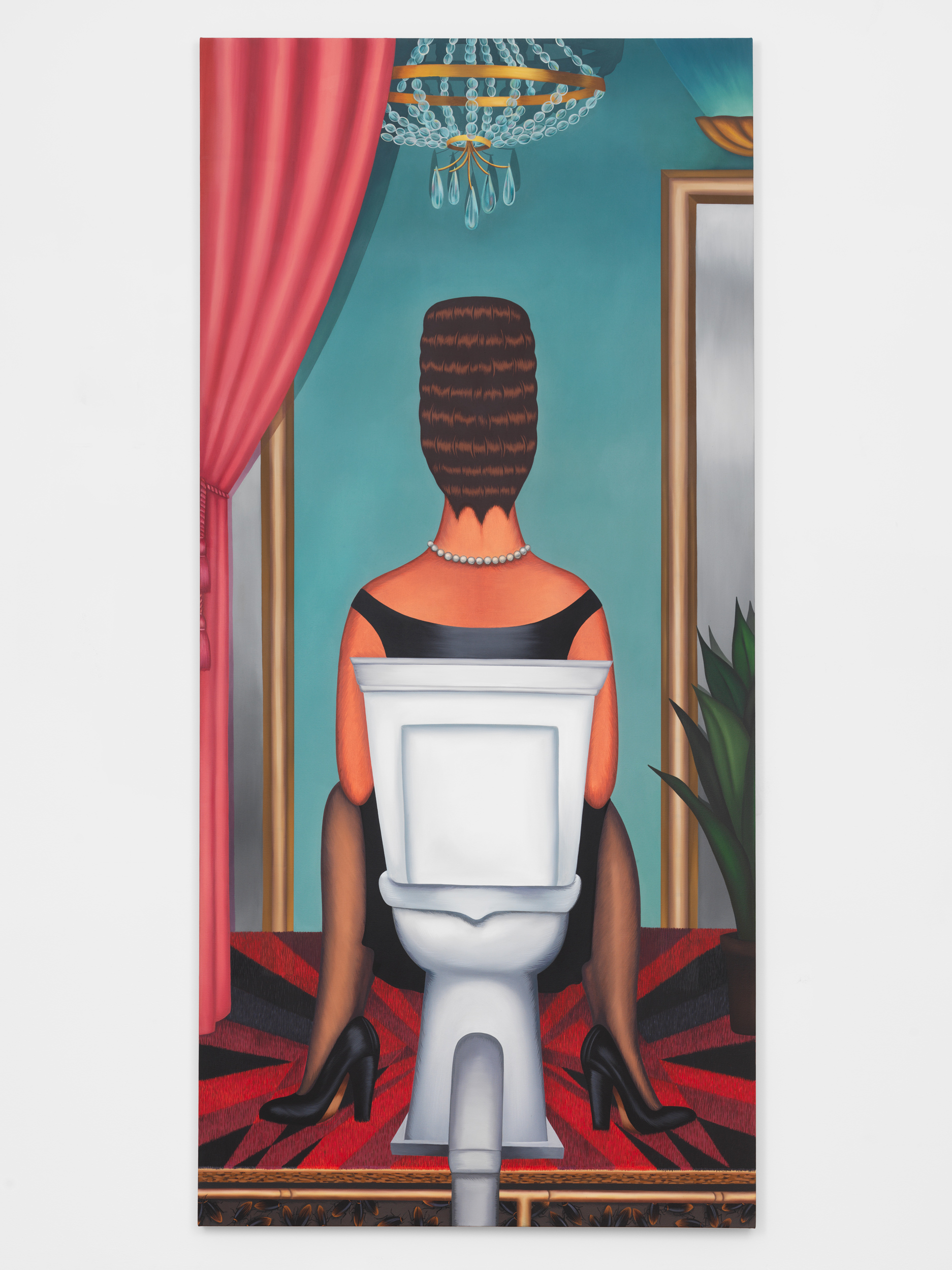

'Fluff War' and 'Wildlife' are on view through June 15, 2019 at Anton Kern Gallery. All images courtesy the gallery. Lead image: 'Untitled (Exhibition of Dust)' David Shrigley.

Stay informed on our latest news!

'Fluff War' and 'Wildlife' are on view through June 15, 2019 at Anton Kern Gallery. All images courtesy the gallery. Lead image: 'Untitled (Exhibition of Dust)' David Shrigley.

Accompanying the new installation a floor above, Ad Reinhardt: Print—Painting—Maquette similarly contemplates light and color through more traditional media. The show celebrates a series of prints, Ten Screenprints by Ad Reinhardt, the artist made in response to his traditional paintings. It is smartly curated, a sharp presentation of a complex body of work. A work on paper “ur-proof” is framed aside its accompanying finished print — the idea and its execution. In this way, we can see how Reinhardt worked to transmute his oil paintings to the hyper-flat surface of a screenprint. It feels like it was curated by an art teacher, eager to show the process as its own form. It is a nice show and seems in line with the numerous works-on-paper gallery shows and fair presentations of other contemporary masters this fall (I want to ask the aforementioned Christie’s exec: “In our current macroeconomic environment, are works on paper inferior goods, macroeconomically speaking? Like, because of the vibecession?”).

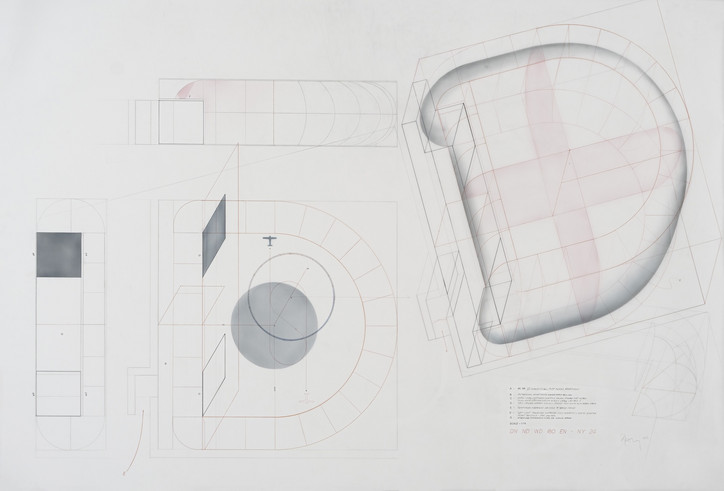

And then downstairs, Doug Wheeler. For the buzz? But there are no phones allowed; you won’t see it on TikTok. Even the gallery’s glossy photography seems to keep the piece, DN ND WD 180 EN - NY 24, 2024, at a distance, presenting it as an almost lifeless backstage. I snuck in just before the gallery closed for the evening. The line was still long — "how many people thought they were waiting for free alcohol?”, I wondered. You are allowed to view the work in shifts, and gallery docents usher small groups of people through at specific intervals.

As you wait to enter, you sit on a bench beside a rubbish bin of crumpled protective booties, similar to ones you might wear touring an apartment on Billionaire’s Row. From your seat, you can see into a glowing room, subtly fluctuating in luminosity and laced with occasional cool purple tones. The installation has only one passageway, so you see the faces of the previous group as you enter: almost certainly awestruck and delighted.

My viewing companions were an affectionate couple and a solo woman. We entered a cavernous room featuring two sheets of light — the platonic ideal of a white cube. I initially thought the booties were props in commodity theater, but immediately, was impressed by a quiet space free of any marking; its hermetic qualities are essential to how DN ND WD 180 EN - NY 24, 2024 works. In front of the glowing portals — almost oversized depression lamps — are two quadrilateral inlays made of glossy epoxy rather than the painted matte white of the rest of the room. They feel like shadows to the light walls, and I was careful to transgress them initially, not knowing what was precious and what was participatory in the space. I gingerly slid onto them, approaching the walls of pure light. The best comparison I can make is to the windows of the aliens’ ship in Arrival. Having this reference in mind, and summoning my best Amy Adams, I looked through the portals to a misty and otherworldly space of unknown dimension. It was clear to me what was going on: ahead was a sheet of glass, mysteriously recessed behind some kind of beveled frame and beyond a misty room with some sort of light installation hidden among fog machines. It was nice, I thought, a subtle perceptual trick, a refreshing moment of quiet in Chelsea’s maelstrom of glass and speculation.

Imagining glass, and the ensuing tragedy of a migratory bird flying to its brisk end on the glass of a Billionaires’ Row skyscraper, I was careful in my approach. I inched my head closer and closer to the light wall, and finding nothing, looked to the docent for a suggestion on how to proceed. He smirked and motioned me forward. I took a step and entered a white void.

I started laughing. The woman started laughing. Beyond the light walls is a “ganzfeld”, a featureless room within which light itself feels thick, voluminous, and softer than it does elsewhere. I walked forward into seemingly endless space knowing logically, though somewhat disbelieving, that I would soon hit something. Eventually, my feet caught the slope of the floor, seamlessly curving up to join an invisible wall. My first experience of DN ND WD 180 EN - NY 24, 2024 can be best described as near-constant discovery. The work does not yield itself to quick-glance judgments, what you think is happening is often incorrect. The initial room of the installation, what I later understood as an antechamber, is pleasant, but underwhelming. It was not the heaven I was promised. However, each subsequent exploration — stepping onto the epoxy, moving through the portals, and walking around the ganzfeld — felt daring and unexpected.

I could describe the work poetically: behind all seen things lies something vast; the process of knowing is a path that can only be walked in one direction. I could find a metaphor. Plato’s cave is the most salient. Or maybe gender: the passageways as a fictively dualistic representation of gender norms, the ganzfeld the truth of our unbounded humanity. Or perhaps psychoanalysis: the vestibule, the superego; the passageways, ego; and ganzfeld, id –– arrange this set differently, my Freud is rusty. Or, narratively and spiritually: the vestibule is a pleasant purgatory of sorts (maybe life itself), the passageways faith and disbelief (or death, two ways), and the ganzfeld a serene plain representing the most optimistic notion of the persistence of our souls. But Wheeler and Zwirner offer us no such poetry, only the concrete referent of DN ND WD 180 EN - NY 24, 2024 a plane flying through night and day’s transition wherein to change direction is to gaze upon a different temporality entirely.

To this end, a purple light begins on one side of the field and slowly dissipates before swelling subtly on the other side of the space. The light seems to decrease in luminosity at some points, feeling materially heavier or lighter depending on where you are in the work. I had walked to the edge of the work, in line with the passageways, when I began to see a subtle pool of shadow, defining an area of the floor. I walked through it, tracing out the outer edge of the installation. For another passage, I focused on the sounds I was hearing while moving through the work. As I walked, I spoke to myself, enjoying the incomparable echo of that space. At once, I felt a pressure in one ear and noticed that I could only hear the echo coming from that side. I realized that I had, through sound alone, found the precise centerline of the installation. In these ways, the work can really only be made sense of through experience and exploration. Wheeler’s installation seems to spatialize intuition itself, wherein the viewer is forced to trust embodied knowledge in an encounter with art, a very rare moment.

Doug Wheeler, DN ND WD 180 EN – NY 24, 2024 © Doug Wheeler. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner.

Doug Wheeler is a first-generation Light and Space movement artist (think Robert Irwin, Larry Bell, and James Turrell) and a lifelong pilot. He has described flying as total immersion in light, a disorienting situation in which directions can become confused. For this work, a mature ganzfeld study from the 84-year-old artist, Wheeler has condensed his considerations to the precipice of a day as observed from the air. Having never flown, my understanding of this phenomenon is largely informed by the writing of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, who described the deserts of his crashes as similar to flying through a void. Wheeler’s installation is the closest I have come to feeling the sensations he described. Wheeler articulated his early hopes for his work in a 1968 interview with Time magazine, saying, "I want the spectator to stand in the middle of the room and look at the painting and feel that if you walked into it, you'd be in another world." Only 56 years later, he has given us that other world.

Photographs of his work are almost crass. Visitors look as if on a Hollywood special effects stage, dwarfed by flat nothingness. A camera cannot capture the strangeness of being in a space without knowing its volume or the completely enveloping field of light that is the ganzfeld. But they do show something essential about his installations, a body suspended in light. Though it makes a boring photograph, when you are that body, all you can perceive is that light, as thick as space itself.

The work is so elemental, so stark, that it is difficult to describe using precise language; it is difficult to speak about it objectively for this reason too. It is most comparable to an architecturally scaled sensory deprivation tank, and I found myself wondering, on a very literal level, where the work ended and my imagination began. Most visitors leave swearing there is a fog machine hidden somewhere. Wheeler’s work draws a fine line between desolation and hallucination, literalizing and materializing light itself. Within DN ND WD 180 EN - NY 24, 2024 I found myself thinking about the vacuum of space. It is difficult to imagine a void because light and matter are ubiquitous in our experience of existence — we often experience air and darkness as emptiness, though true emptiness is not something we have ever encountered. Space itself feels thick inside Wheeler’s installation, and the work allowed me to feel the presence of my existence as a being made of matter within a constant soup of other matter. There, surrounded by more things than in most moments of my life, I was able to imagine nothing.

Since experiencing it, I have craved it almost hourly. There is a house I visit in my dreams every other night or so. In it, there is a hidden room only accessible via a secret pathway. In months past, I have not been able to find the room, and, when I have, other people have been there. Recently, Wheeler’s ganzfeld has taken its place. I will leave a space and suddenly will have entered its void.

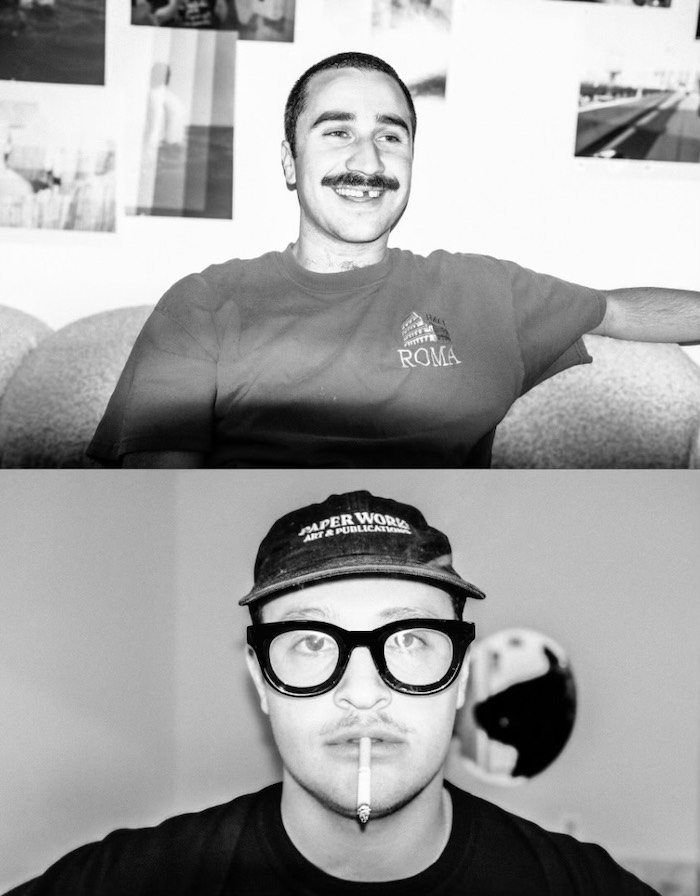

Noah recently founded PRIV.Y, a creative agency and production company based in the Lower East Side. As the gallery’s director, he had been patiently waiting for the right project to debut within the space, a project that would empower artists like Tommy and himself and truly highlight the strength in unity. AM/PM was the perfect place to start.

office sat down with Noah and Tommy after the exhibition came to a close — but ahead of their plans to release an AM/PM book sometime later next year — to discuss Tommy’s craft and what it was like organizing their first show together.

Noah Berghammer— I first met Tommy when he came by my studio in Chinatown and we instantly clicked personality-wise. We're both quite spontaneous and outgoing people. But I think Tommy and I kind of balance each other out — I'm a raging optimist and Tommy's kind of like, 'Eh, I don't know,' about that stuff. That day, he told me about this concept that he had, which was AM/PM. Tommy, you'd had this concept for a while and it's kind of taken different shapes and forms other than what we created. Do you want to talk a little bit about different forms it's taken and where the idea came from?

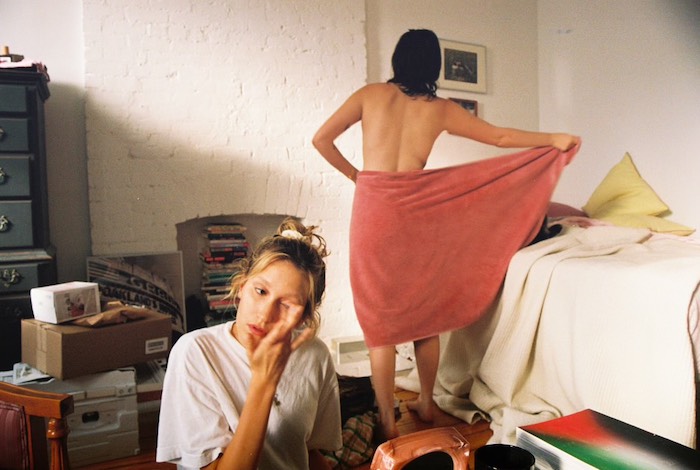

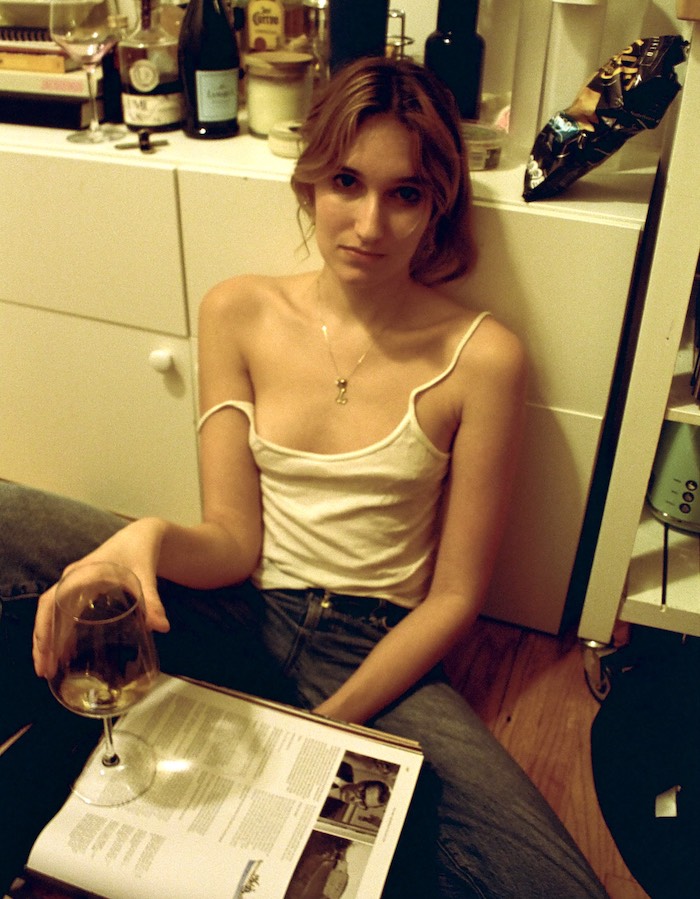

Tommy Rizolli— I grew up in the city of DC, and being out with my friends and having independence was a really prevalent factor in my childhood. So it makes sense that my work then progressed into just photographing my friends, whether it's editorial work or more documentary-based work, like this project. When I moved to New York, I was introduced to some really special, hardworking artists that ultimately became some of my best friends, along with people that I had been friends with for a really, really long time. So it was initially conceptualized as I had been shooting my friends in New York and then maybe two years after that, I was like, 'Oh, that'd be cool to do a book or something.' The concept highlighted this juxtaposition of my really tight-knit group of friends here, in the daytime and then at nighttime.

NB— That was the thing that was really drawing to me. I feel like I've grown so much as an artist since moving to New York because the city forces you to, based on how much you're intaking the people that you're meeting and the experiences that you're having. I hadn't heard anybody really define it in a way that was so clear until Tommy talked about AM/PM. Because when I first moved to New York, I would meet all these people at parties, at events, at Fashion Week — and I'd think, 'How do you actually become friends with these people?' To me, my daytime friends were the people that I turned into real friends. So it was funny having somebody else come in with this whole concept that illustrated that so well. I don't even think that I had really seen many images from your concept of the show. I was really just drawn to your work at large. And to the concept, and then to you as an artist. Tommy, I know you talked about a book, but was the fine art context ever something you were thinking about within your work?

TR— I don't think so. I can’t really describe what my work is. I think something that's important to me is, at least when it comes to photography, that style can be a hindrance. For me, themes in my work are more important and, in my work there are always a few, but the overarching one is that the people I photograph — whether it's commercial work or personal work — are people that I'm really genuinely close with and have a real connection with. So yeah, I wouldn't say fine art was in the back of my mind. I don't even know if I knew that that was a way to describe certain styles of photography. I just wanted to shoot the shit I wanted to shoot. I didn't really give a fuck.

NB— Having been your friend for a year and a half, you've been so unwavering to that motive. I get frustrated with Tommy every once in a while because he chooses not to shoot commercial work. But then you see in the images why they work, it's because there's a relationship there and nothing is forced. I'd always wanted to have this physical space for my community to find refuge or to be able to show work or perform. I was thinking live music venue, I was thinking cafe, I was thinking concept store. But then I thought, 'What could a gallery or an exhibition space look like if it's also an office and also a performance space?’ — kind of like this shapeshifting, melding place. And when I was able to secure that, I thought to myself, 'Now I have a gallery. Who do I show?' And you immediately popped into my head. Having gone through that whole process together, I know that it was pretty emotional for you to go through the negatives and whittle down what images would make the show. You want to talk a little bit about the curation process?

TR— Yeah, I mean it was really cool. First it was looking through all the negatives and then cross-referencing those with the selects we wanted in the show and then figuring out which ones we wanted to hand-print. It was super emotional. I mean, it was five years of living here just flashing before your eyes. I have a newfound gratitude for my friends. People come and go, but it's nice to see how close we've all gotten and the people that have remained.

NB— A lot of these relationships and these connections that we have to people, we don't really have a clear definition of why they are so special. When I look at your work, especially in the context of all of it together, what I feel are very emotive feelings, but I don't really know what they are. When I see you riding on the dirt bike across the Manhattan Bridge, I don't really know what that makes me feel, but I know it makes me feel something, you know? It's defintiely an emotional process when you're going through work and then you're giving it context and then you're dealing with why that context was important to your life. I know that some of those images touch on past relationships. They touch on friends that you're not really friends with anymore. They touch on people that have remained for 20 plus years in your life. It is really kind of like sitting back and saying, 'This is who I am.' So when you're thinking about yourself as a photographer, or better yet as a person, who are you?

TR— I think I've always had a lot of confidence in knowing that my friends are special. They're good people and they're really hardworking and talented. Maybe they don't take themselves seriously, but they take their work really seriously. I was happy to just be with them and be able to document them and live in those moments with them. My memory is so bad, but I can look at any photo and I can tell you, almost down to the day and what year it was, what we were doing and what street it was on. That's another part of why I was so emotional. It's just like, holy shit. That was five years ago. Time flies.

NB— And I really loved listening to you recall those things when we were going through the images. Kayla, it took us so long to whittle down our selects. I genuinely don't think we had our selects until about two weeks before the show. We started with about 80 or 90 images and we wanted to whittle it down to about 25. And I think it really came down to Tommy, your memory, it was like, 'Yeah, this might be a better image, but nothing was happening there.' Whereas another image had a really meaningful memory attached to it. You're not really that traditional photographer in any way, shape, or form [laughs]. So I was curious in looking through these photos with you, when do you decide to take a photo?

TR— It connects back to what you were saying. I have such a deep emotional connection to the photos just because of how I was feeling in that moment. I don't know if it's tangible. I either get the feeling or I don't. Like with Dom for instance, it was just pure joy and freedom and risk. Or with Jalen, it was volatile and it was really fun and sad. I think it's just about whether or not I really feel a strong emotion. But I'm definitely not a technical photographer by any stretch of the imagination.

NB— The way you take photos, I think, is reflective of the type of person that you are. When I asked you what was important to you about doing a show, it was just that people thought your images were honest. There is no more honest image than the ones that you choose to take in moments where you feel something. I think all artists can relate to that to some degree. I don't even know if you take photos of strangers ever.

TR— Right. No, it's not my thing.

NB— I'm sure there have been times in your career where it would've been really easy to just commit to being a street photographer or a studio photographer or something like that. But I think your sheer defiance against that has been what's really guided you. I'm not necessarily saying that it's always comfortable or easy to do those things, but I think the reason people gravitate towards your work is because of the attachment that's there. It's not because the images are using the best source of light or that they're super technical. I think there’s so much more to be said about you taking the photo rather than the photo that's being taken.

TR— Thank you.

NB— Talk to me a little bit about the whole idea of having a show about you. How do you feel about that?

TR— That aspect, as I'm sure you know, is not my forte [laughs.] I think it was easier for this because it felt like it almost wasn't even about me. It felt like the show was about my friends so I think that was easier for me to digest. It's definitely hard receiving compliments. The marketing and the promotion of it is definitely something that I'm not good at or something I'm super interested in. But I know it's important. I am really happy to be the one to take the pictures and I do think my friends, in a lot of ways, are a reflection of me. So I do think there were some aspects in the show where I was like, 'Okay, this does have me in it.'

NB— I think it has a lot to do with your selflessness as a photographer as well. You really do want to show the best parts of the people around you. I feel like that's what I noticed being in the room with 200 people at our opening. Your dad actually came up to me and he said, 'Doesn't he have a way of just making all the people around him feel so special?' And I thought that that was something that just was really powerful and impactful because you do have that charisma about you. And I think that when you choose to take a photo, it's almost like saying like, 'I love you.' You know what I mean? This is just your way to tell your friends that you love 'em.

TR— I think that's a good way of describing it. Yeah.

NB— How do you see your career going forward as a photographer, now having drawn this line in the sand?

TR— I definitely want to focus more on shooting in studio. I love editorial work. Something that is always in the back of my mind is, 'Can the way I photograph translate into that setting?' I have shot editorial stuff before and that's something I want to explore more. I just want to continue photography in my own way. That's the most important thing.

NB— I think what's been the most important for me to realize as well, as an artist, especially someone who's young in New York, is that there's a lot of energy around hustle and making it for yourself. Now taking on the role of an agent and an art dealer, I'm having to really step on the opposite side of things and say, 'Well, what's even important to you as an artist?' One thing that I've realized about Tommy is that what's important to him is staying really true to himself. I have to find a way to continue to empower artists like Tommy in spaces that I can now provide without losing why I'm doing it in the first place. And I think that that was why it was such a beautiful experience to be able to start that show with you Tommy. It felt like some semblance of success, but I think I honestly, for us, it would've been successful if we just got the doors open. Can you talk a little bit about the experience of us working together on this and this being our first real show?

TR— Yeah. I mean, I thought it honestly went pretty well. Something I really appreciated was that you gave me a lot of space and respected my creative decisions. I felt like we communicated and we worked through some adversity.

NB— Having gone through something like that, it just made me super proud to be your friend. You don't really know what kind of friendship you have with somebody until you do something of substance together. I think it was exactly what it was supposed to be. It's a beautiful thing when you can make things like that come together. And the only way you can do that is with the help of your friends.