Think Giggle

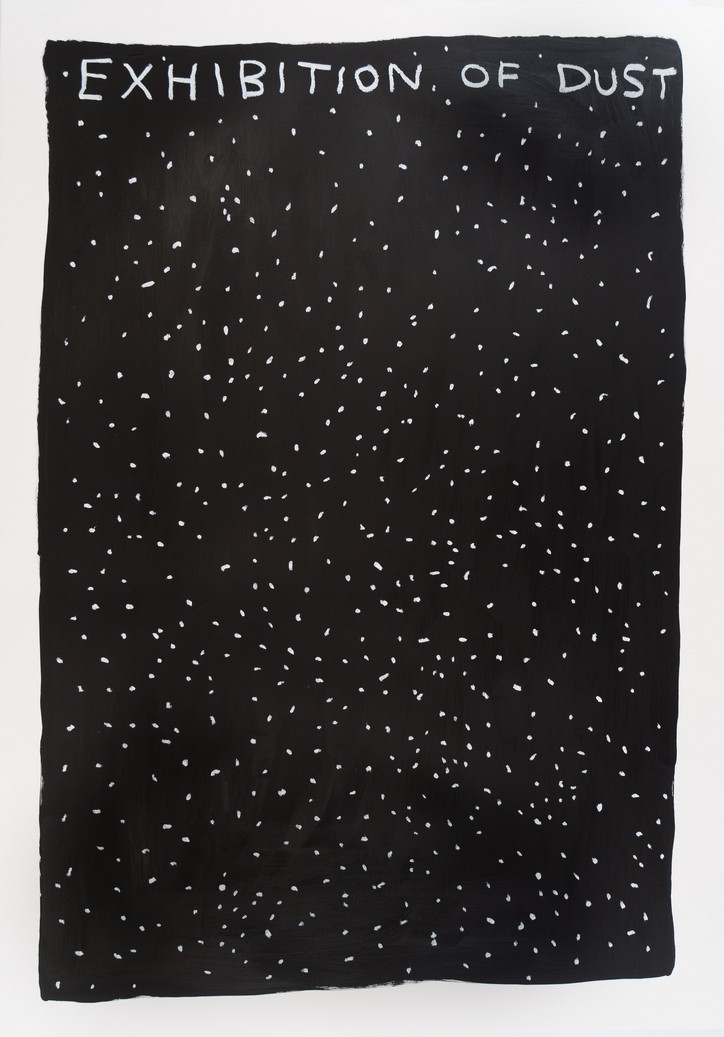

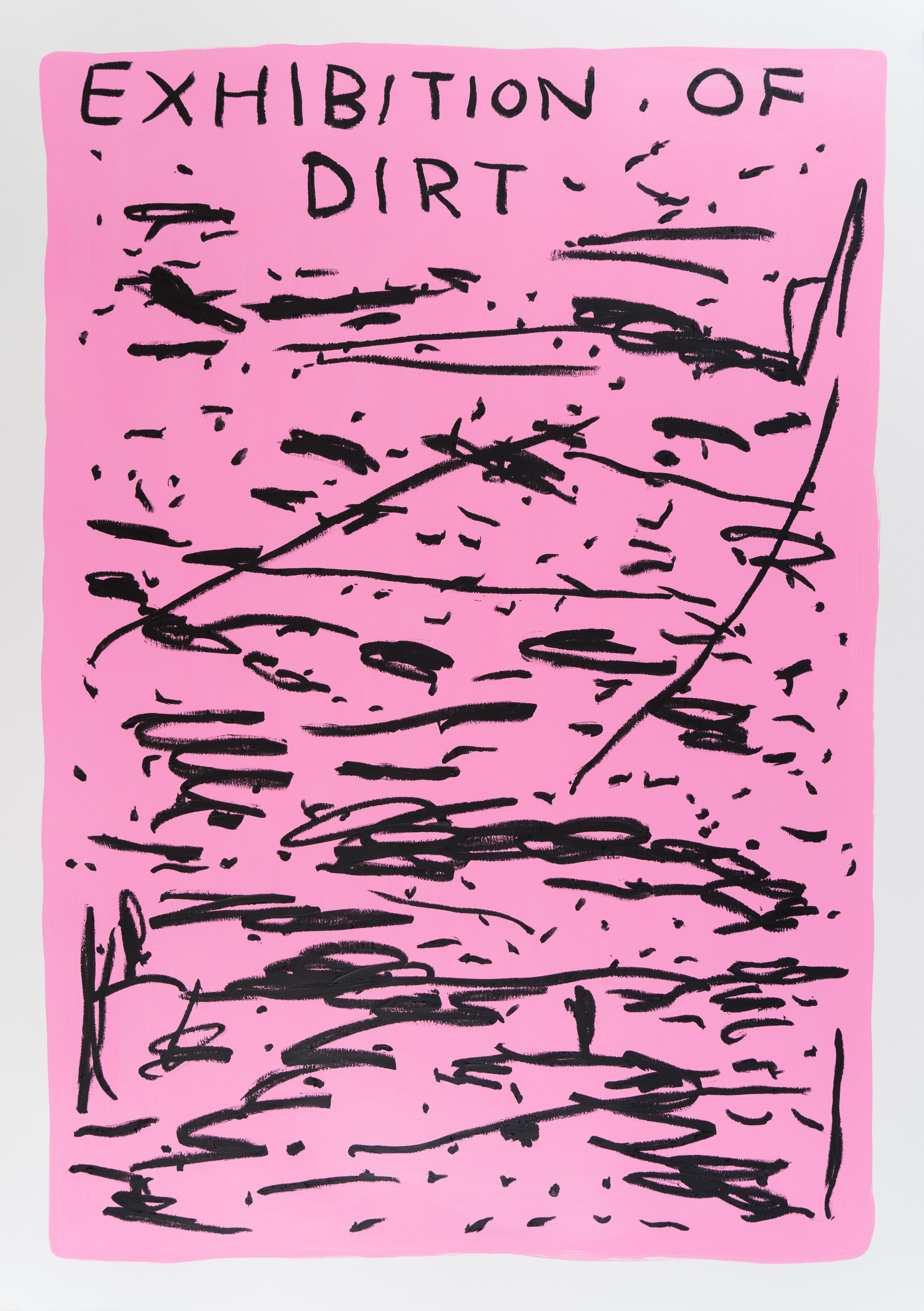

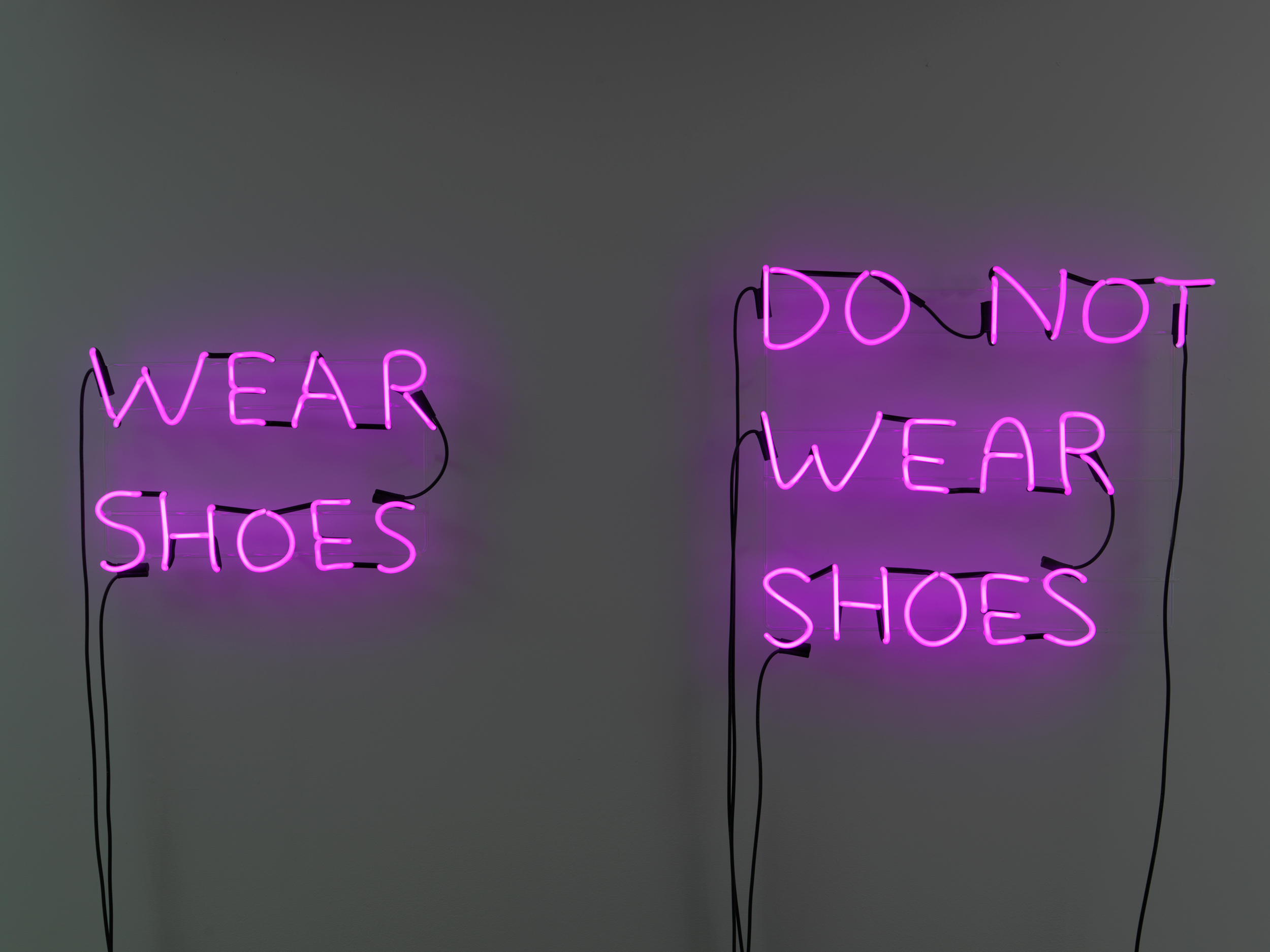

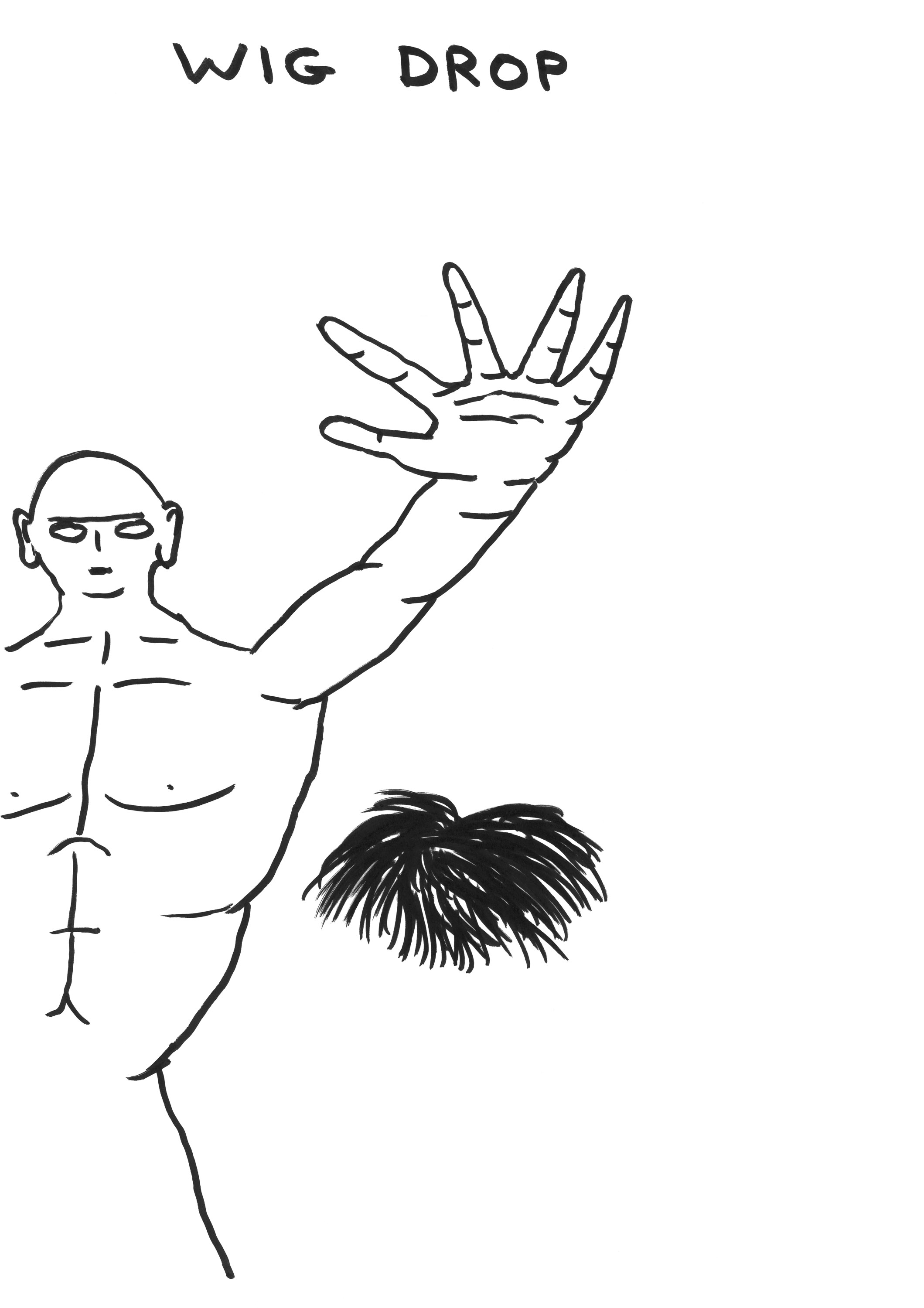

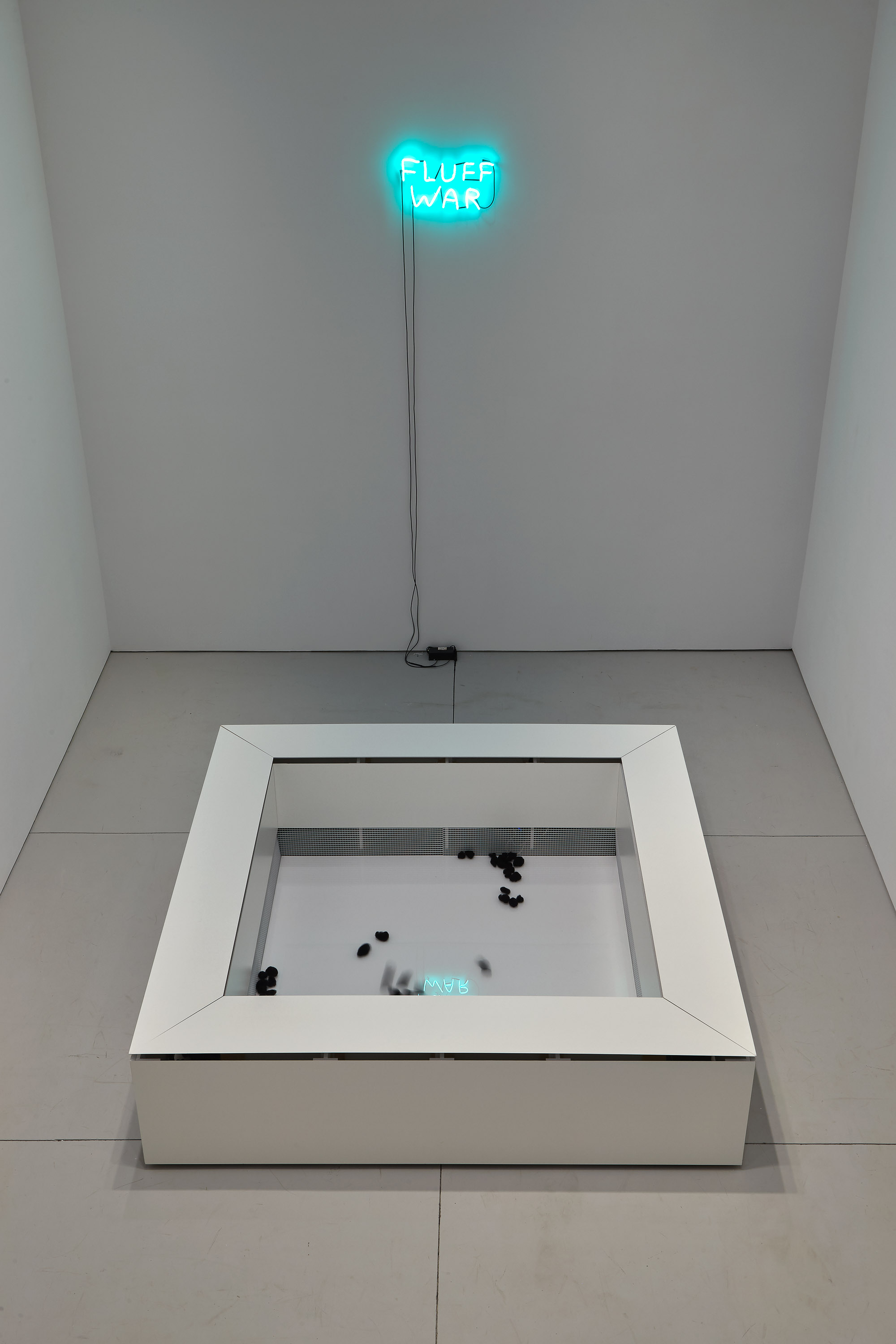

'Fluff War' and 'Wildlife' are on view through June 15, 2019 at Anton Kern Gallery. All images courtesy the gallery. Lead image: 'Untitled (Exhibition of Dust)' David Shrigley.

Stay informed on our latest news!

'Fluff War' and 'Wildlife' are on view through June 15, 2019 at Anton Kern Gallery. All images courtesy the gallery. Lead image: 'Untitled (Exhibition of Dust)' David Shrigley.

She and Pollack struck early, making the pioneering move to respond with art. The duo debuted a sprawling, star studded online group show, then moved along to digital solo shows spotlighting artists like New York painter Judith Bernstein. By summer, ATLT presented their first public art project—20 billboards across the five boroughs in partnership with Save Art Space, animated by artist-activists such as Helina Metaferia, who has since joined the organization’s advisory board.

Part of ATLT’s staying power stems from its timeless central question: “How can we think of art at a time like this?” Turns out that’s always valid. “We're throwing the question back to artists,” Pollack, who birthed the name, explained. “How can we rethink art at a time like this? How does crisis make us think about art differently? What kind of art can we make in response to crisis?”

Verhallen told me ATLT considers artists thought leaders. “We wanted to create a space where we can view their works in a nonprofit setting, and really let their works speaks for themselves.”

These days, ATLT is going coast to coast, taking on mass incarceration and climate change—and harnessing collaboration. In 2023, they partnered with the Natural Resource Defense Council to present “How On Earth” at EXPO Chicago, offering artworks by Metaferia, plus installation artist Jennifer Ma, performer Janet Biggs, and landscape architect Lily Kwong.

In this beat between ATLT’s blowout anniversary bash PUBLIC hotels' ART SPACE last month and their first gallery show (around censorship, this Autumn) I caught up with with three repeat conspirators to debrief on what they’ve learned these past five years, and where they’re going.

You first connected with ATLT when Barbara invited you to stage an online solo show. How did you choose which five paintings to put on digital view?

JUDITH BERNSTEIN - I chose them because they are all iconic works!!! The first and second pieces, Birth of the Universe #4 (Time, Space, and Infinity), 2012, and Golden Birth of the Universe, 2014, equate human birth with the birth of the universe and puts women at the center (where they should be!). The first work, Birth of the Universe was shown a few times and was the centerpiece for my solo exhibition at the New Museum in 2012. Golden Birth of the Universe was a commission for Studio Voltaire, London where it served as a humungous altar piece in the church turned exhibition space. The next three paintings, President, Money Shot/Yellow, and Money Shot/Blue Balls have been shown under blacklight for maximum impact, which is always a killer!! A retinal overload!

Online exhibitions have pretty much faded away since the old normal returned. But, did participating in your own alter how you looked at your work—or art in general—at all?

JB - In person viewing is always much more impactful. There is a lot that is lost online: the scale, details, textures, the hand of the artist, lighting, space, the presence of the work, etc. However, when that opportunity is not available, online still allows for engagement with the art and democratizes the viewing by providing more access.

Your art has been political for more than 50 years now. It feels like the same issues won’t go away. Has your opinion about art's role in society shifted? Why do you keep making?

JB - Making art is my passion and obsession. I make art for my own needs and not for the popular market. Art for me is a calling and not just a business. It’s my rage at injustice! The politics change, but there are many underlying issues that remain the same—economic and social inequity, political repression, gender bias, and the horrors of warfare.

What topics do you plan to tackle next?

JB - I just had a solo at Kasmin, New York with my “Death Head” series, which keeps evolving. These gestural paintings feature heads that appear at once transfixed in awe and in a state of active alarm, reflecting the tension fundamental to the poetic dyad of life and death—my contemporary response to Edvard Munch’s scream. This series addresses the horrific moment that we’re in. This time the strong men, I mean the dictators, are hijacking the political realm. The current timeframe is a reenactment of the 30s and we are now on the precipice of World War III.

Since your practice often involves talking to people and going places, and ATLT’s debut billboard installation took place during the pandemic, I was wondering—did you select an artwork you'd already made, or was this something that you produced during lockdown?

HELINA METAFERIA - I adapted something that I had made the year before. I've been making this work prior to the 2020 uprisings, and so it felt like a service of my work to utilize it for social justice and art spaces and public spaces. So yeah, I've been working at the intersection of art and activism with a focus on women and non-binary people, and thinking about ways in which archival research often doesn't fully encompass our labor within activist histories. I've been working with that theme for a while, and sometimes people are into it, some people feel like it might not be a pressing issue for them. But then, timing brings the work to the surface. Luckily, the work is there and accessible and ready for those moments. I mean, we're in another moment where the question of ‘Art at a Time Like This’ is very pressing. As artists, our job is to keep making the work. And we never know when we'll be called upon, but we should always be prepared and ready.

I love that you created a social practice rubric for your students at Brown to use. How would you evaluate this particular billboard activation, for instance?

HM - As if we're looking at a sculpture or a painting, there can be talking points. There can be ways we can organize a conversation. For the social practice element to this public art project, I would consider thinking about the ways in which it used the limited resources that were available in a way that’s its own creative pursuit. Like, curating is a creative practice in itself. I think they acted in a timely fashion. They engaged artists and community, and created activations around it. An organization was developed and was formed. Many social practice projects start with one show, one work. Then quickly the need starts to grow, and you want to formalize that, to have some sort of structure to support it. If you look at the work of Rick Lowe or Theaster Gates, they started as individual artists, and then it quickly emerged into organizations and nonprofits, and they become institutions within themselves. I think Art at a Time Like This has kept its grassroots feel, but it's quickly growing as an organization that is here to meet the needs of artists and cultural producers and art workers when there is precariousness—and there's always precariousness—so their value will always be there. But it started as a one-off project, and it just kept growing. And I think in that way, the scaling up of it reminds me of a lot of great social practice work.

People wonder if every original idea’s been had. Like, what can still happen with art? I do think social practice is it—especially because there's such a disconnect between the values the art world alleges to espouse versus the values it actually practices. Do you have thoughts about how social practice might grow in art over the next 50 years or so?

HM - The term itself is new—only like 20 years old—coined in 2005 through institutions, right? It takes art historians a decade or more to really articulate what artists are doing. So what we're doing now, it's yet to be defined, and we won't be able to define it readily until years to come. That's what history does, allows us to contextualize. So, I mean, it's quite unpredictable, because it's still brewing. It's gonna be related to what happens with our nation, the international, global art world, but also what's happening in the world, right? Artists respond. We don't make art in vacuums. We respond to our environments and our conditions, and we have a platform—a privilege—that allows us to speak to the most challenging aspects of society. That's what contemporary art does.

I think there are people who don't want to see contemporary art flourish because it has a critical voice, and artists have a lot of agency. Artists are always going to make, first of all, but the future of any art form will be determined by the greater geopolitical circumstances. It'll be determined by freedom and democracy and ability for free speech, whether it's overt or covert. Artists will always make, as I said. Whether it'll be concentrated in Europe or in Asia or in Africa or in the US will be determined by governments. I think the beauty of any art form is that so much is unknowable.

While we wait for history to be made, what are you working on?

HM - I'm in a group exhibition that Barbara Pollack curated at Jane Lombard Gallery in New York City. It's called Facial Recognition, and it's up through April 26. I have a solo exhibition at Project for Empty Space, which is a nonprofit in Newark, New Jersey. That’s open May 6 through the end of August, and it’s curated by another powerhouse curator group, Jasmine Wahi and Rebecca Pauline Jampol. The title of that show is “When Civilizations Heal.” It's an interdisciplinary exploration of 60 years of activist archives led by women of color. I'm premiering a work in progress of a feature film and showcasing new collages and sculpture and video and installation. I’m in some group shows now at Palais de Tokyo in Paris, called “Collective Joy.” At LACMA, called “Imagining Black Diasporas.” Oh, and at the Knoxville Museum of Art called “States of Becoming.”

You never know, as an activist artist, whether things are going to slow down for you when there's political turmoil, or if things are going to speed back up because people want the work. Time will tell. But my overall message to any artist who works at the intersection of art and activism is just to keep going, to keep making the work. The resources may expand, may shrink. The audience for your work may expand, may shrink. You really can't control that. All you can do is remain consistent and authentic and work through the studio practice, the community engagement, the performance, whatever it is. Work through that from a place of integrity, because that is more of an inner work that supersedes the outer circumstances. It's a continuous dialogue between you and you, in response to the world.

I love that you helped plant nature in the white cube at EXPO last year. Did conceptualizing “MOTHERFIRE” for the environmentally taxing fair context lend any new angles to your explorations around art and climate justice?

LILY KWONG - I have always felt that my mission is to reconnect people to nature and their community, both plant and human. My focus is to bring plant life to some of the most challenging environments in the hope of sparking awareness, curiosity, communion and connection. As a few examples, my team and I have built mountains in Grand Central Station, created a jungle in industrial Brooklyn and created urban greenspace in downtown Los Angeles. EXPO was the same—my intent was to plant the seeds of an ecosystemic and spiritual awakening to consider the more-than-human world. I focused on the circularity of what I could control, and our saplings were re-homed and the Shou Sugi Ban posts were returned to the fabricator for re-use. All we can do is our best.

Which plants did you pot in the work’s 55 Shou Sugi Ban posts? How did you choose and source them—and keep them alive throughout EXPO’s run?

LK - I worked with the incredible horticulture team at Theodore Payne Nursery, whose mission is to educate about the beauty and ecological benefits of California native plant landscapes. Through their resources, I’ve learned about wildfire resilience and California's fire ecology and wanted to create a monument to the regenerative possibilities of native plants in fire-prone regions. We contract grew saplings with Theodore Payne’s team: Ceanothus spinosus, Rhus integrifolia, Heteromeles arbutifolia, Juglans californica, Prunus ilicifolia, Pinus sabiniana and kept them alive through the loving care by our project manager Shannon Lai. Some of these trees are not only incredible food resources for mockingbirds, robins and even coyotes and bears, but they are also fire retardant like Toyon and Lemonadeberry. Others are considered fire-responsive like the ghost pine, which is actually highly flammable but its seed regeneration is favored post-burn and its germination increases with fire. Native plants are uniquely adapted to survive and thrive following a burn since they have co-evolved with fire for millennia. With MOTHERFIRE, I wanted to honor fire as a core element of our local ecology, both as a contributor to our rich biodiversity as well as an ever-looming threat

You had your first show at LA’s Night Gallery last fall, and debuted a public artwork in New York’s Madison Square Park this month. Out of all your roles—mother, architect, organizer—do you see “artist” growing fastest of all?

LK - I would say Mother is the fastest growing—a role that I have found fundamentally transformative to my psyche, spirit and body. Though ‘artist’ has expanded immensely alongside motherhood, or likely because of it. Having two children in three years has given me much more confidence as a creator—what is more artistic than growing a spine? An eyeball? Kidneys?? My show Solis with Night Gallery emerged from my maternity leave with my daughter, an explosion in a new medium created largely with her by my side. New Motherhood, my favorite piece from the exhibition, was in many ways my first artistic collaboration with baby Gaia, whose marks live all across that piece. I have found that for me, mother & artist are inextricably linked.

What’s your dream project?

LK - Gardens of Renewal at Madison Square Park is truly a dream project. It’s been an aspiration of mine to build something for the iconic park since I first took landscape design courses at New York Botanical Garden over a decade ago. Our Meditation Garden and Children’s Garden has been almost two years in the making. Gardens of Renewal is an offering, a prayer for humans to be brought back into harmony with nature and for balance, peaceful co-existence and reciprocity to be restored to our society and ecosystem.

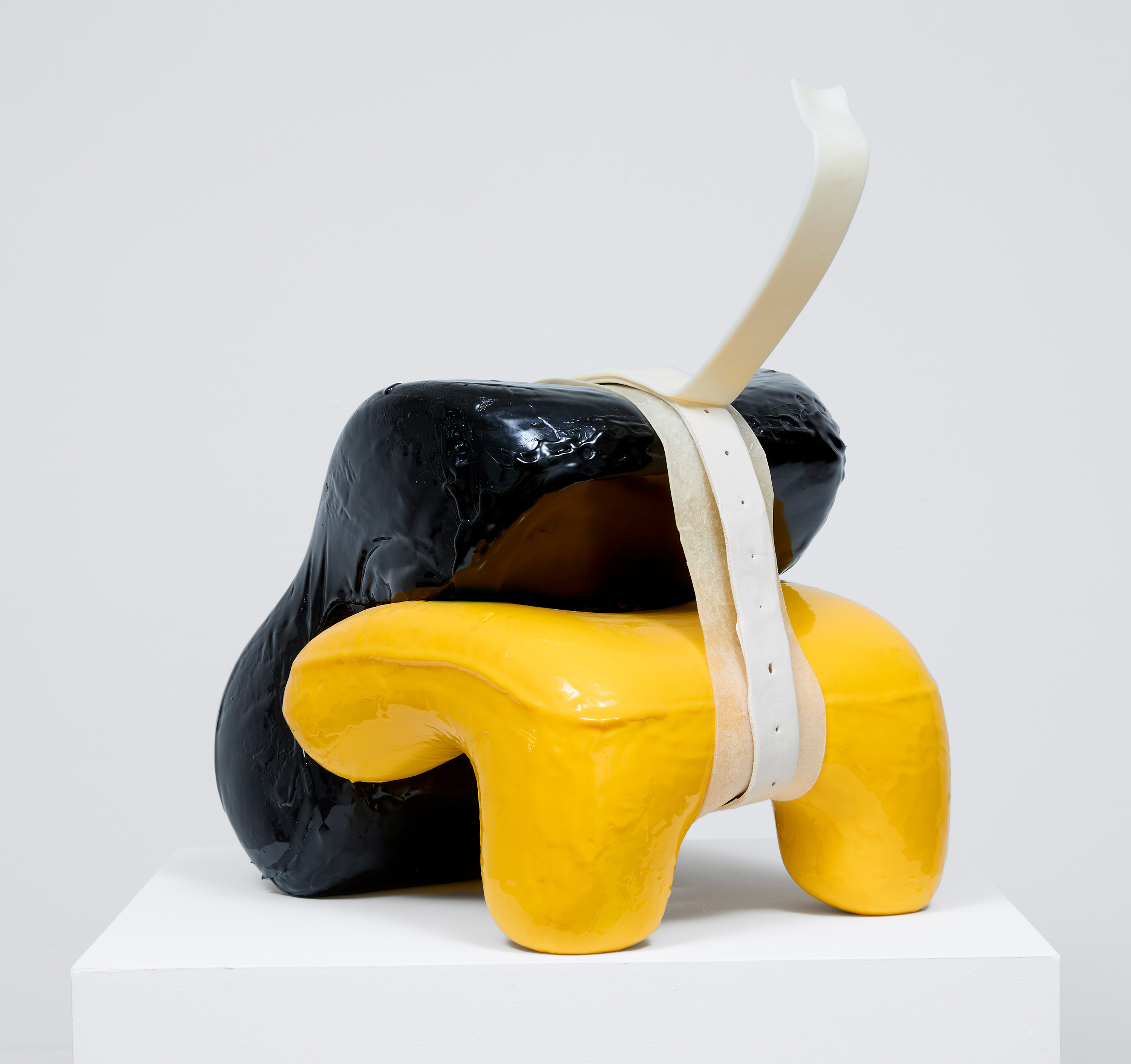

Continuous Squeeze is your first solo show in a decade. How have you been working on your sculptural practice without the pressure of making a show? It seems that there is a mystery or privacy to your works that does not fall into trends or categories.

I am in the studio on a regular basis, I’d say on average 3-4 days a week. So, whether I have an immediate deadline or not generally does not determine how offer I’m working in the studio. Studio time for me is split between different activities or “work/labor”. I usually have at least one thing that is progressing well and moving towards completion, one that appears or feels like it’s stuck or stalled and then there is something or new material I’m experimenting with or trying to further understand and whether it has any future place in my work, or not. It is this last endeavor that is the slowest process with no guarantee that anything will be accomplished.

And yes, the studio is isolated from others, meaning I do not have a staff of studio assistants with a definitive set of tasks to perform. I generally work alone which allows for risk and discovery, no audience to watch me have a bad day in the studio or fail. The studio for me is a very private head and body space which I think allows me to be less inhibited.

As to the 10-year period two of those ten were effectively surrendered to the COVID pandemic when it came to studio visits and public venues. This was also when both of my galleries (Team Gallery and Richard Telles Fine Arts) effectively closed, which looking back on it proved to be somewhat liberating for my studio activity. At the time it was a lot of what I thought was bad news all at once however it all probably came at the right time for me. I’m now enjoying the change of scenery.

A central part of your practice is exploring how inorganic materials can become organic-looking. Tell me more about your interest in creating this kind of visual effects?

Thinking and talking about the space between the organic and inorganic is a curious thing. There might have been a period when we lived in a world where these two were clearly defined. Now I know scientifically they still are and mutually exclusive. But I I’m not so sure that’s haw we as a species experience the two. We seem to live in a time and space where the two slip in and out of their ontological categories or definitions. The “organic” and the ‘non-organic” are increasingly becoming conflated. How else would you describe our fledgling relationship with AI or CGI.

Now I’m still working with “real” materials and fairly 20th century methods of object making/ rendering. But I’m interested in how the natural, whatever that might mean, and the un-natural join or intersect or maybe just collide.

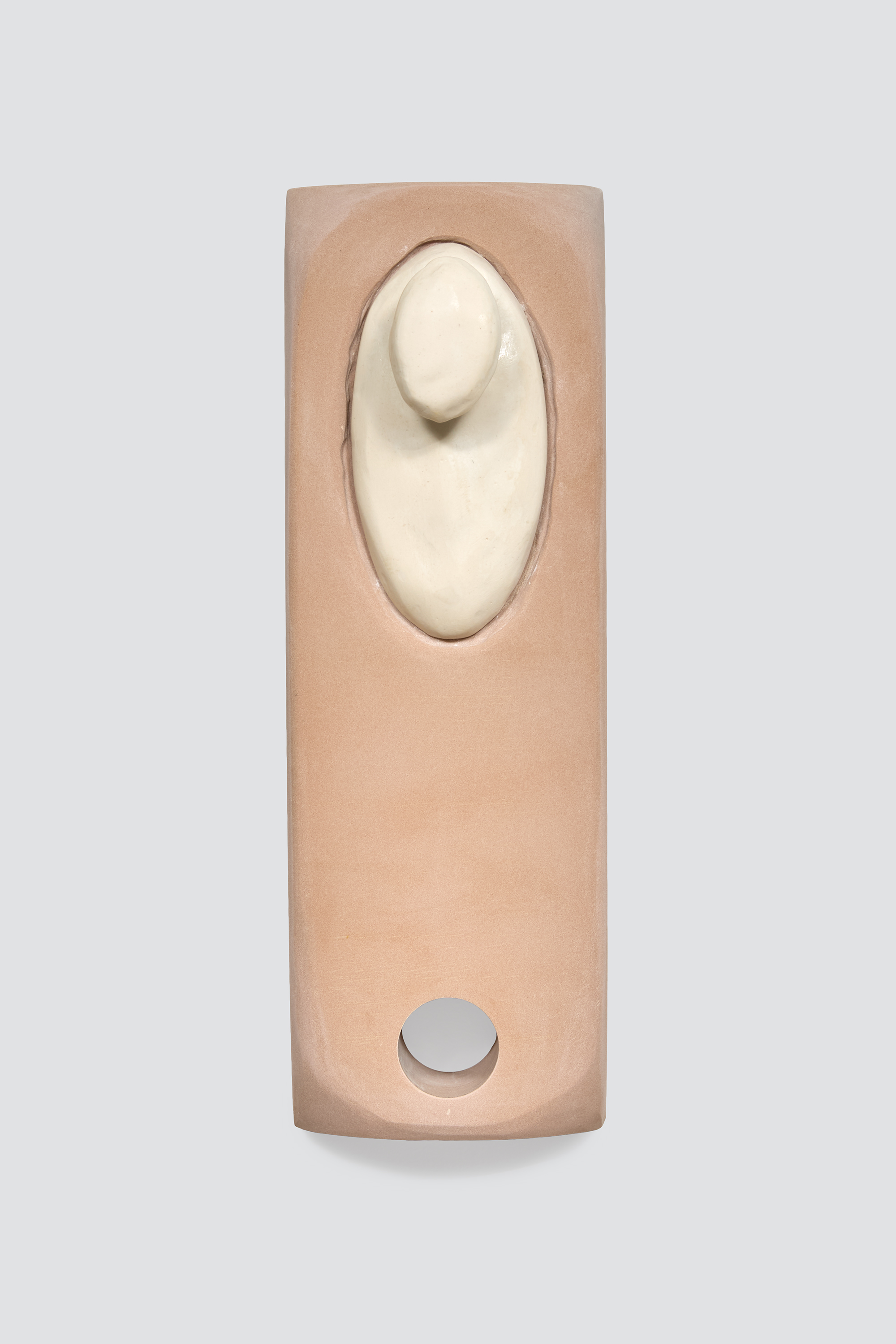

The erotic, acts of coupling and decoupling, is paramount across your body of works. I am especially fascinated by how you combine erotic imagery with visual perspectives. A sculpture that seems clinical can appear to be ludicrous at a different angle, such as Coupled Prop (white, green), 2025. How do you think through shifting interpretations in your work?

I love thinking about the phenomenology of objects. Their shapes and possible meanings through association, both familiar and not so. Sometimes a thing can be both familiar or understood and then quickly shift into alien obscurity or the abstract. A lot of what humans do or to be more precise invest in is kind of ludicrous. Over designed fetishism can be found everywhere we (humans) have had complete control over. Look no further than the kitchen gadgets and high-end bathroom architecture/design that is venerated. It seems to me that most of our production values are born out of the act of arousal. Value has extended beyond basic needs or task completion. We live in a period when corporeal arousal is value dominant.

Your earlier works seem to be more interested in tensions of mutual dependency or thresholds, whereas your recent works are more about how the human form can be evoked in the absence of a human body. What motivates this shift from constructing an intricate system toward hybrid structures between bodies and functional objects?

Well, whenever you have two or more things (objects) coupling up to form one dependency as a subject is always present in the narrative. What I’m interested in is that space or gap between the surrogate (stand in) and the accoutrement (ornament/equipment).

Another dimension of your exploring hybridity is that your recent sculptures often play with surface and depth, especially through using negative space. I am curious as to how you think about dimensionality.

I would consider myself a sculptor in the truest sense of the word. Which means I find myself thinking about fundamental attributes that define both an object/sculpture and how we coexist with it. So, things like space and time, surface or skin, weight and volume are paramount.

The motifs of wellness culture often recur in your sculptures. What attracts you to the culture of self-optimization?

This is such a great question and topic, wellness culture and our pursuit of self-optimization.

If we look at Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs diagram wellness culture of self-optimization might find itself positioned at the top of the pyramid under the heading “self-actualization” but with a sometimes-weird twist to it because this wellness culture end game seems to try and cheat mortality. Which is the most un-human thing I can think of.

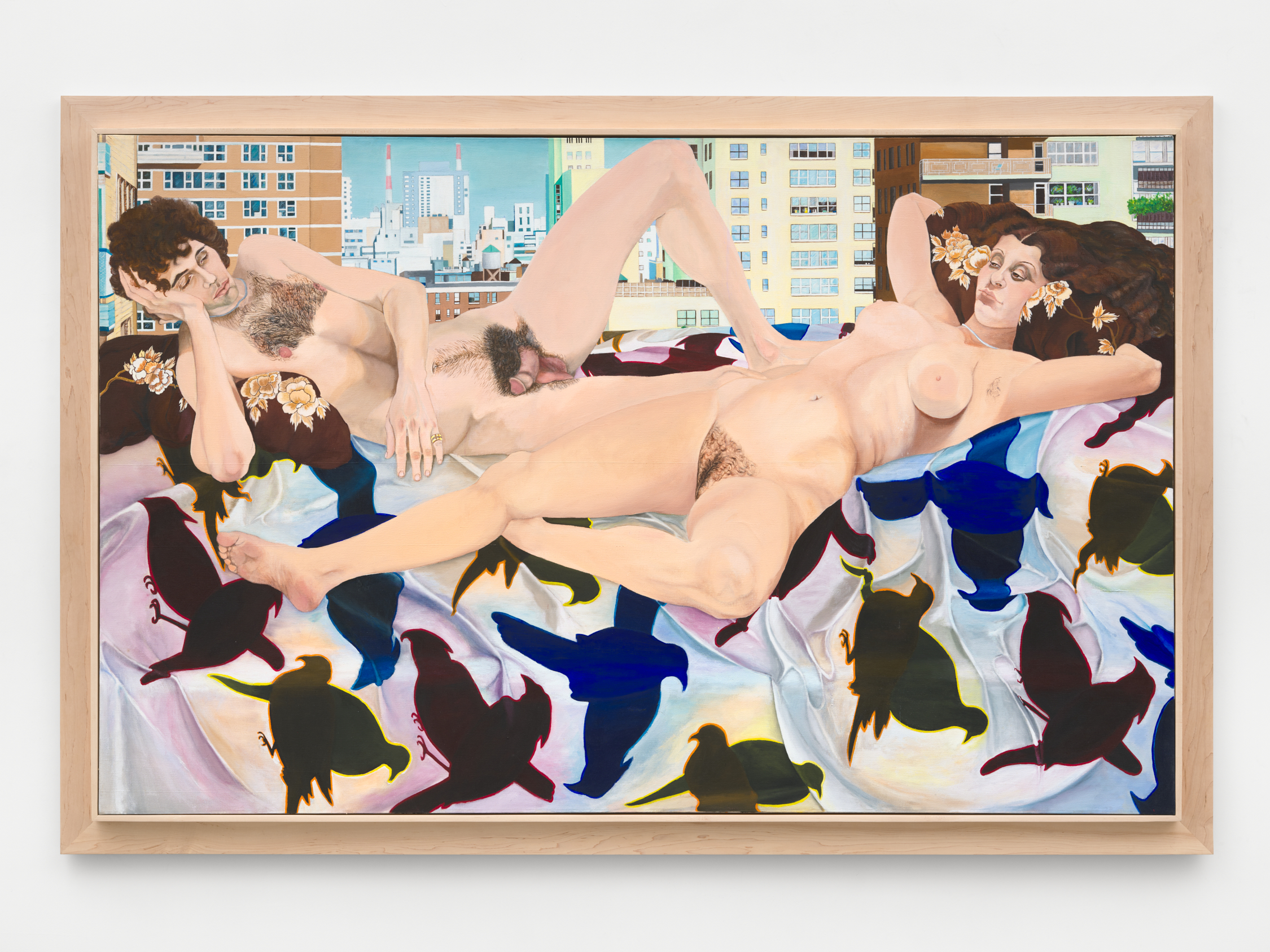

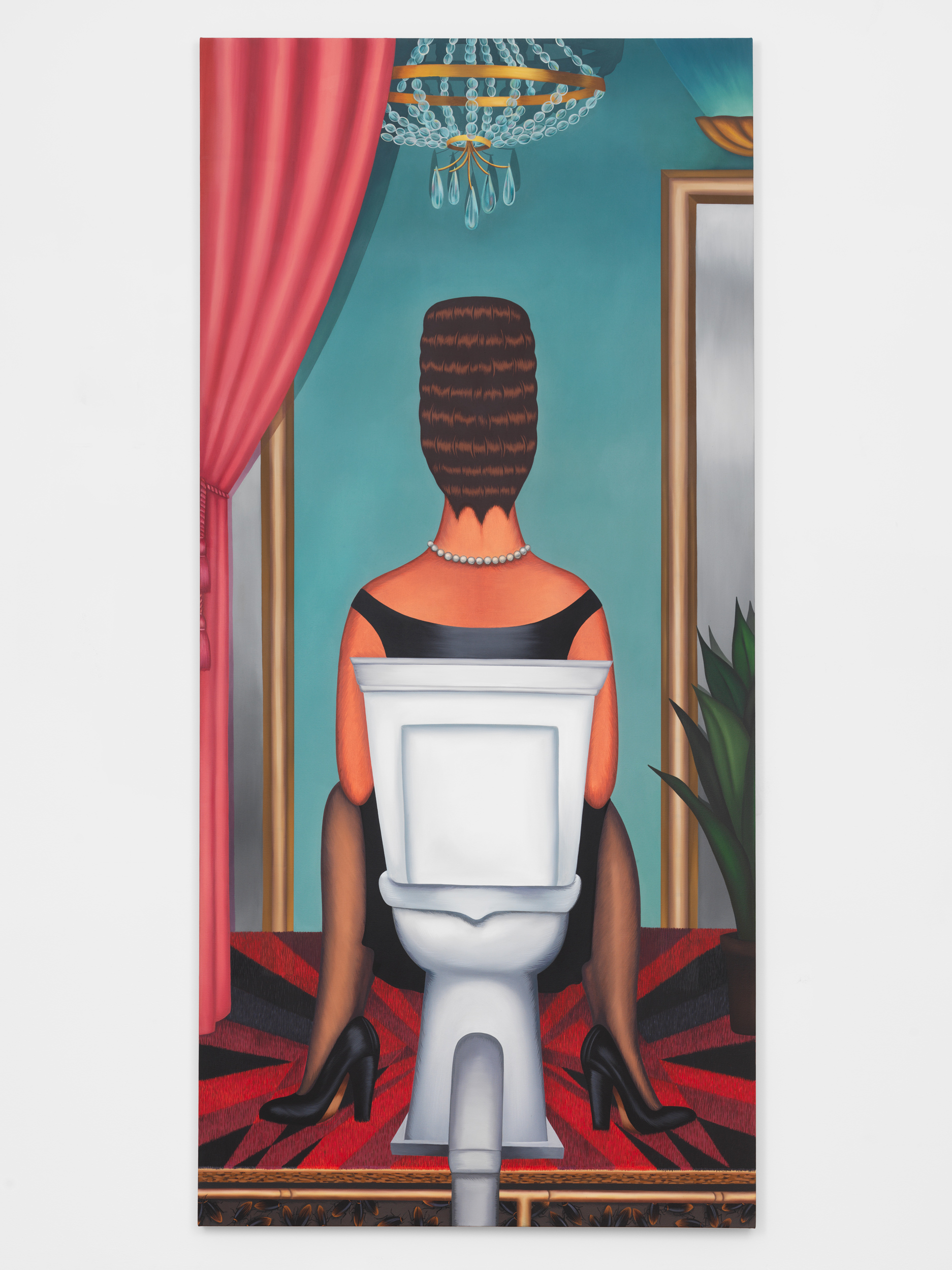

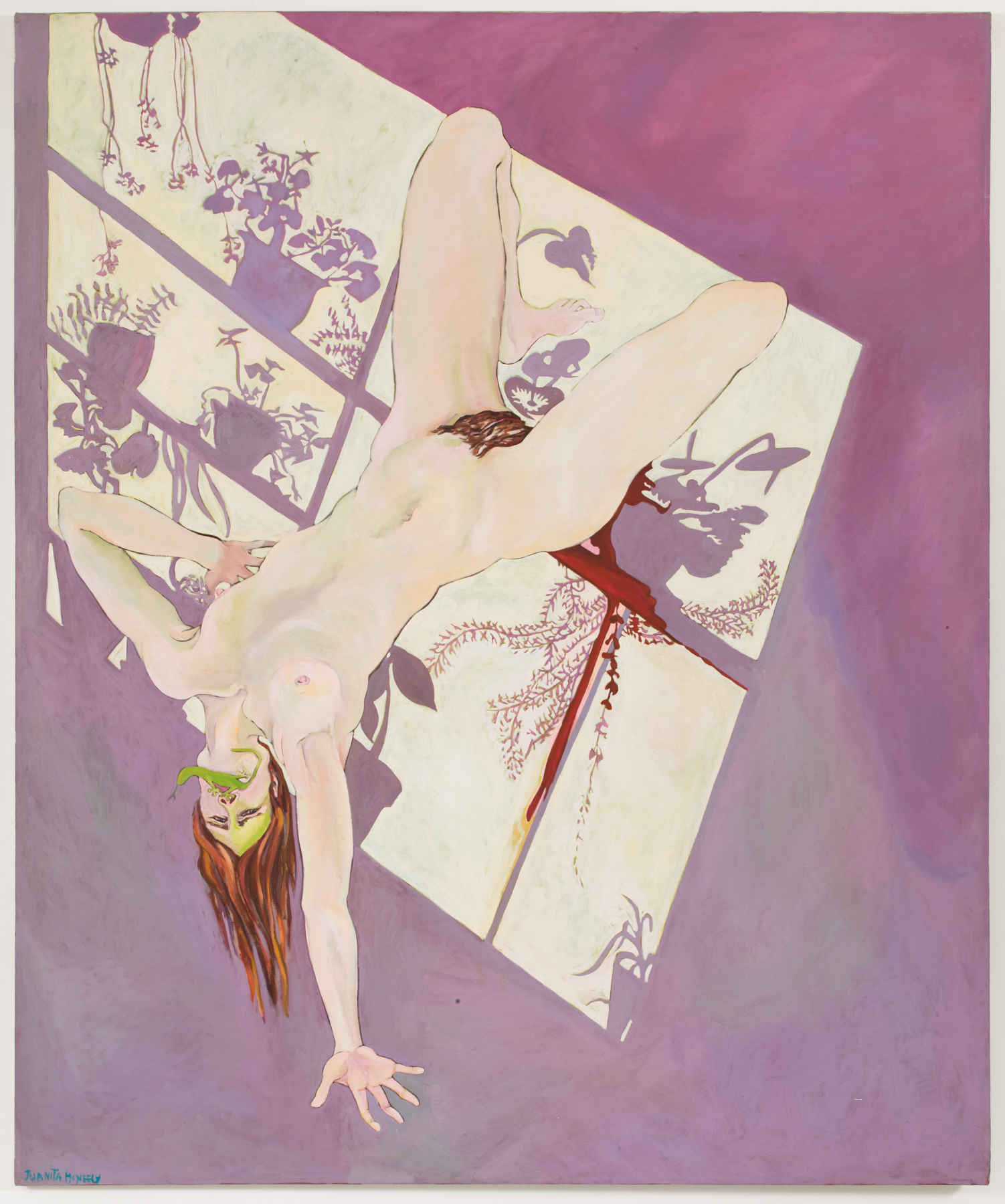

The show’s namesake piece, Anita Steckel’s Giant Women on New York (Coney Island), 1973, is part of her greater Giant Women series. A nude woman, stylistically larger than other figures, lounges outstretched in the water of Coney Island beach. Known for mixing erotic imagery with recognizable landscapes, Steckel protested art history’s double standards by portraying female nudity on her own terms. Her figures take up space both literally and figuratively in her landscapes, emphasising an ongoing uphill battle for women to secure their place in the cannon.

In 1972, a Republican legislator demanded that Steckel’s solo exhibition, The Feminist Art of Sexual Politics, be cancelled, considering her works too obscene for the public. Steckel responded to this accusation by forming the Fight Censorship Group, which would go on to advocate for the right for women to use male nudity and sexual subject matter in their art works, just as men did. While we might like to think this kind of censorship is some far off dystopian reality, it’s all too familiar to the political control we’re facing again today.

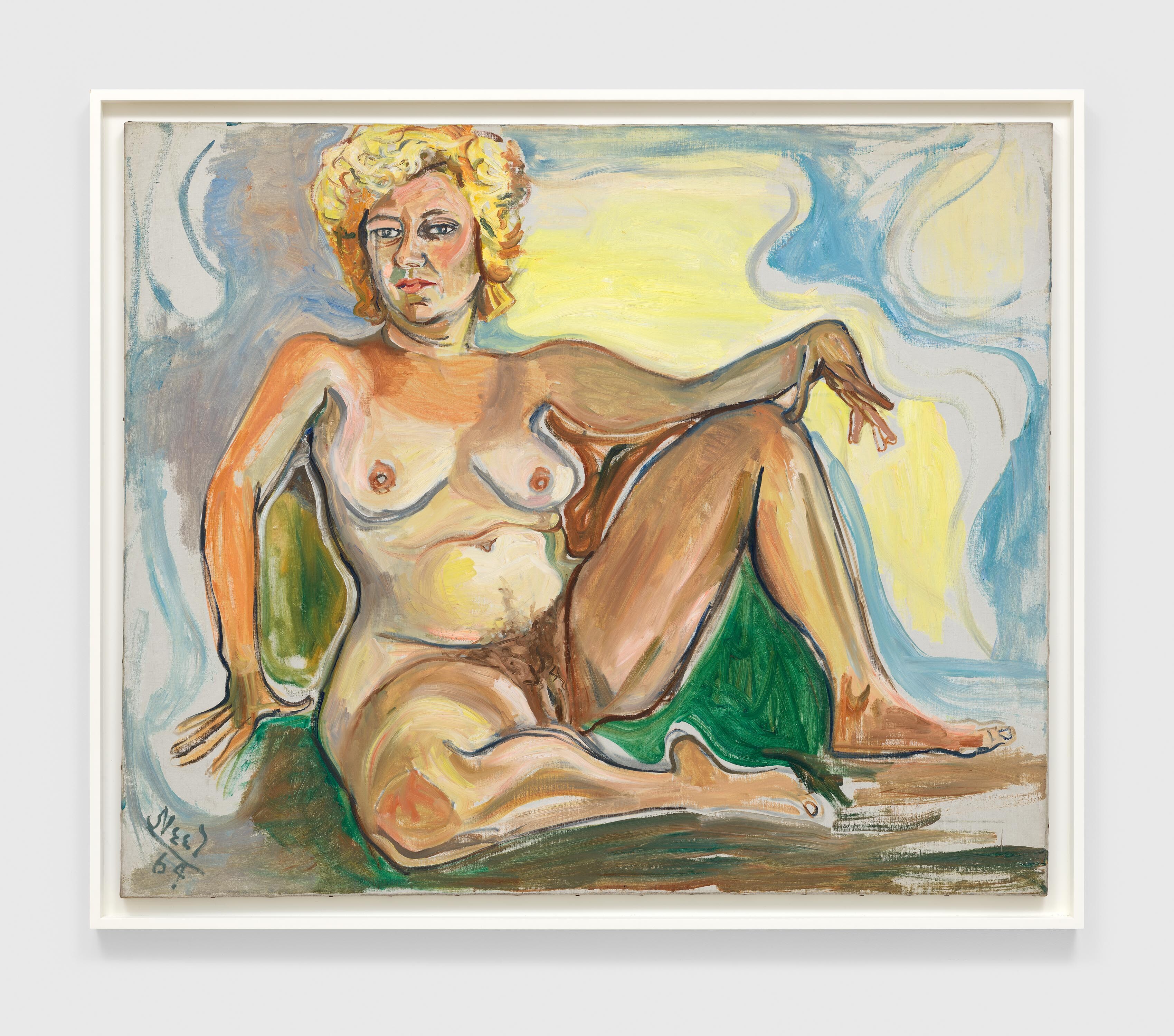

Bringing female experiences to the foreground of painting was part of a larger initiative to give humility and dignity back to the sitters, especially when painted in the nude. Male artists often depicted their models as mere sexual objects or muses, painting them as nothing more than nude flesh, disengaged from personhood. Alice Neel was uninterested in producing the next Grande Odalisque, and opted to humanize her subjects through her honest and raw depiction of the nude figure. In Ruth Nude, Neel’s unforgiving re-examination of the female body takes away an overly idealized exterior. In doing so, Neel provides an opportunity for the viewer to inquire about the sitter’s inner psyche.

This unvarnished approach to the body can also be seen in the work of Joan Semmel, who began as an abstract expressionist and later turned to figurative painting. Her sexually charged imagery was part of a larger second wave feminism initiative for women to explore and get in touch with their bodies as a means of taking back ownership.

Semmel did this by painting her intimate angles of her own aging body, depicting its inevitable changes. In other pieces, she intentionally leaves the face of her figures out of the frame, allowing the viewer to impose themselves into the work. She depicts visible sexual pleasure from a woman’s perspective, outwardly rejecting the male gaze. Bottoms Up (1973/1992), is part of a larger Overlays (1992—96) series, combining an underpainting from her Erotic Series (1972), with later imagery from her Locker-Room paintings (1988—91). Semmel revisits the same themes throughout her life, emphasising the lifelong commitment she has made to her figures.

These women not only refused to sacrifice the woman for the artist, but created a community to support a greater discourse surrounding what stories we highlight in art history. Giant Women On New York seamlessly demonstrates this unending determination to compound the worlds of activism and art, while also revealing how much work there is left to do.

The art landscape is changing quicker than we can keep up with, and with that, our commitment to the figure seems like a distant memory. Giant Women On New York feels like a call to the past, a point of reflection in a time of turmoil. There is work to be done and work to protect regarding women's rights. The works of these “giant women” provide us with opportunity to ruminate on the complexity of the female experience, and encourage introspection.