Tommy Cash Dropped a New Single, but Who Really Gives a Shit?

Watch the new music video below.

Stay informed on our latest news!

Watch the new music video below.

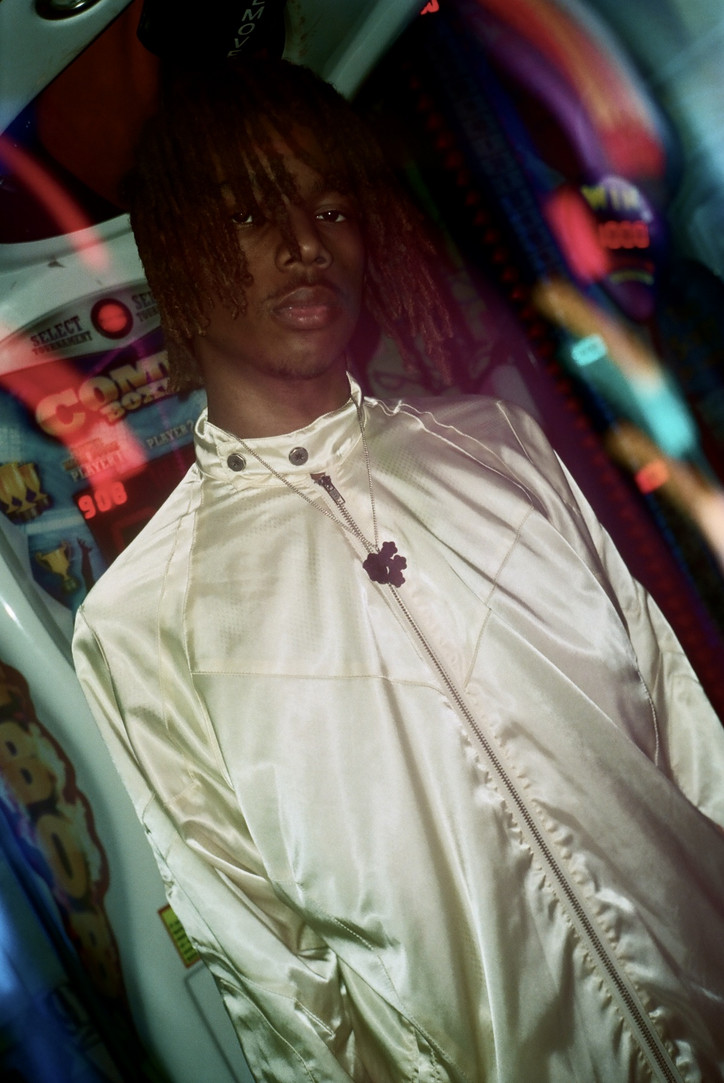

Since 2020, Midwxst (his real name is Edgar) has been making brutally honest tracks that are sparked with fried, hyperpop beats. Sometimes they're loud, sometimes they're cocky — and at all times, they give the feeling as though you're looking in the mirror with him. Lately, though, he's been trying out a new sound. On his latest debut album, E3, he's simply doing whatever feels right for the song. Throughout its twelve tracks, there are saxophone solos, vocals lent by Ye's Sunday Service choir, and an interlude by his grandparents. But, change or not, he's continued to keep the one thing that's made him resonate with millions of listeners, particularly those who see him as a channel for their emotions: he's still just as honest.

Eventually, Midwxst ended up coming online, though it wasn't for long. He'd reacted to a meme someone posted. ("This looked like sum else crazy.") But this had been enough for the group, one that was full of people who wanted to be like him, who really liked his music — and all around wanted to be in a space for him, even if it was virtual. It would be a few days later before he would come on again, but, like always, they had been fine waiting for him, too. Until then, they had talked for hours, sometimes about school or other rappers they liked, but mostly, it was all about him.

office caught up with Midwxst to talk about coming-of-age albums, his upcoming E3 tour, and AI.

I’ve been hanging out on your Discord server lately, and I have to say –– it’s a really interesting community. You’ve got people talking about you, drawing you, recording music together that’s inspired by you... When you made the server, was it always your intention to have this kind of space?

Not really. I kinda just made it for me and my friends to mess around in, and then it kind of just ended up growing into something bigger. I always wanted to have, like, a hub of people who were interested in what I was interested in, or cared about music to the same extent that I cared about music, and that was one way for me to make that possible without it being this insane, crazy effort. Over time, it’s just been mad people joining –– like it’s almost at 10,000 people. (It’s now at 10,000.) That’s crazy to me.

I read that when you were first starting out, you were in Discord servers recording with other people. Is this server a lot like the ones you were in?

100%. I think it’s an all-around, full-circle moment because it’s like, I used to be in these environments and now I’m able to create this environment to nurture art and creativity, and it’s just so cool to me.

Let’s talk about E3. Obviously, every artist dreams of putting out their debut album, but for you it was a little different. You didn’t just want to make an album; you wanted to make a universe. Tell me a little bit about that universe?

I wanted to make a universe ‘cause all the influences and things I take in –– outside of being an artist, but as an avid listener –– have been experiences and coming-of-age experiences. Like, for example, you look at My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy by Kanye [Ye], Call Me If You Get Lost by Tyler [the Creator], Utopia by Travis [Scott]…Those are things you can build sonic pallets from. You can envision all of these albums and what they look like, not just off the sonics, but how they’re packaged altogether. So I wanted to try to emulate that intimacy and experience because I feel like it gets overlooked nowadays. A lot of people now are just looking for that hit song or that one song that’ll take the whole record everywhere. But you don’t need to do all of that when you can be well-executed and let your story tell through that. That’s the stuff that I really wanted to speak for itself.

That’s what I wanted people to resonate with and really feel. The best way you can get that is by sitting down and making the whole universe. So you actually wrote lyrics for the first time here? It’s interesting because it’s been said that a lot of rappers don’t actually write anymore. Yeah, I don’t be writing. I mean, I’ll write, like, starters and then after that I’ll freestyle the rest of whatever topic I was thinking of. That’s how I’ve always made music. This is the first time I’ve sat down and been like, ‘Dang, this beat is too pretty to say nonsense over it.’ I gotta make sure I give it justice.

Do you punch in?

I do punch in, but I be punching in in chunks. So it’s like, if I can’t get a line once, then I’ll do the line before it and then that line again to help me get acquainted with it, and then I’ll do that again for the next one and the next one, and we’ll end up building the song from that. But half the time bro, I just be saying shit –– I’m not gonna lie. I’m able to phrase my words well enough, though, so that it works.

Did you make this album in LA?

Yeah.

I saw one of those “Overrated/Underrated” videos you did, and you said LA was overrated. Just curious: how was it making an album in a city that wasn’t really your favorite?

Bro, making the album was the best part of the city, I’ll be so forreal. I’m just not really a big party person and a culture person –– like I’m not overtly outside. And that’s what all my friends or all the people I know in LA do. And it’s like, ya’ll don’t get tired? Ya’ll don’t ever wanna sleep? But at the same time, I also love the city, too –– not even LA, but just Cali. I love being there when it’s not a pain in the ass, if that makes sense. Everytime I’m out there, there seems to be some small thing and it's directly caused by people, and it’s like, I could avoid that by staying here in New York.

Back in 2021, you did an interview with NME to hype up your first tour, and you told them you were excited to perform live because you had songs that “make people want to punch each other in the face.” With E3, where do the songs fall concert-wise?

They were made for that space. I’m touring with a band, so I have a guitarist, a drummer, lights… I haven’t had all of this before. So, it’s something that’s scary, but it’s also exciting. I have a really good setlist, I been rehearsing, eating my veggies, cleansing and getting anything bad out my system. All these songs were made to be played live, and that’s another reason why it’s like –– a lot of people can listen to the music and take away what they want, but until you really feel it… Like, for example, if you just got broken up with and you come to this show, you’re gonna cry. You feel me? Like, that’s what I wanna do: I wanna make someone cry. But then it’s like, don’t forget––I still know how to get turnt.

This tour’s gonna include some special guests. Can you say who they are?

Denzel Curry in LA, Skywater in New York… But I have a bunch of my friends coming, like Caspar Sage, the supporting act, he’s literally one of the most amazing up-and-coming R&B artists that I’ve heard. No glazing –– like, no dickriding, either. It’s me from a completely constructive, music-listener stand point. Like, I get the same energy that Frank had when he first came out, and I ain’t never had that feeling toward somebody in music before. I don’t like revealing too much of who the special guests are, but I like telling people like, “Yo, come to the show. You’ll see what happens.” Every show is different. I might play an unreleased song in Utah, might not in Arkansas. But that’s what you gotta do. You gotta pop out.

Let’s be honest: lately, artist merchandise has gone downhill. Not only is it expensive, but it also sucks. On the other hand, a lot of people (even those that don’t listen to your music) seem to resonate with yours. What were the inspirations behind some of the looks?

With a lot of the designs I put out, I think about if I’d wear this or not. When I made those sweater vests? Those were crazzzy to me ‘cause I always wanted a sweater vest. Seeing people buy them and wear them, too, that was the type of stuff that’s crazy to me. Everything I put out is something I would dress myself in or put on in a day-to-day fashion. I think that’s a perspective a lot of people don’t have. A lot of the time, they just make stuff that they think will sell because the audience listens to them, but it’s just like, "Ehhhh." Imma just make my stuff, Imma just do me.

You tweeted about this a couple days ago, but I wanted to get your take on it here. How do you feel about being turned into an AI?

Yo, no, it’s crazy to me. So my friend sent me a YouTube video, and he was like, “Yo, you on this DC the Don song?” And I was like, “No?” So he sends me the video, and I hear my voice, and they got my nasally-ass tone right, and I was like, ‘Wait a minute? This is a little too accurate.’ So I talked to the guy who ended up making it and he was like, “Yeah! I uploaded your whole discography and isolated some things from your voice to try to get the tone of your voice right, and then the AI made this––” and I was like, “You have so much free time my brother.” But that’s crazy. Like the thing with me, I’ll be like, “Oh, that’s cool. Burn it.” Like, I’ll acknowledge it, but I don’t think AI is something that should exist at all, ‘cause it’s just gonna end up being humanity’s worst decision.

I know you’re on TikTok, so I’m sure you’ve seen videos of, like, Plankton singing “PoundTown” or whatever. What if someone were to post Plankton singing one of your songs? Would you be flattered?

Nah, it would be flattering. I would repost it.

My last question for you: where does the E3 universe go from here?

I feel like right now, it’s a very beautiful time in my life. I have direction and a sense of what’s next, but at the end of the day, I’m not rushing anything. I’m just making sure I have everything lined up. Once this next release starts –– boom, it’s like a domino effect on everything else I’ve been doing. I’m just very excited ‘cause the bar is all the way up here now. I’ve always wanted to constantly keep setting the bar for myself, and it’s really about just working until I’m satisfied with where I’m at again. I think that's the best payoff when you finish a really good song or project, and it’s like a breath of fresh air. It’s like, “Ah, I can rest a little bit.” And then the next thing you know, it’s on to the next.

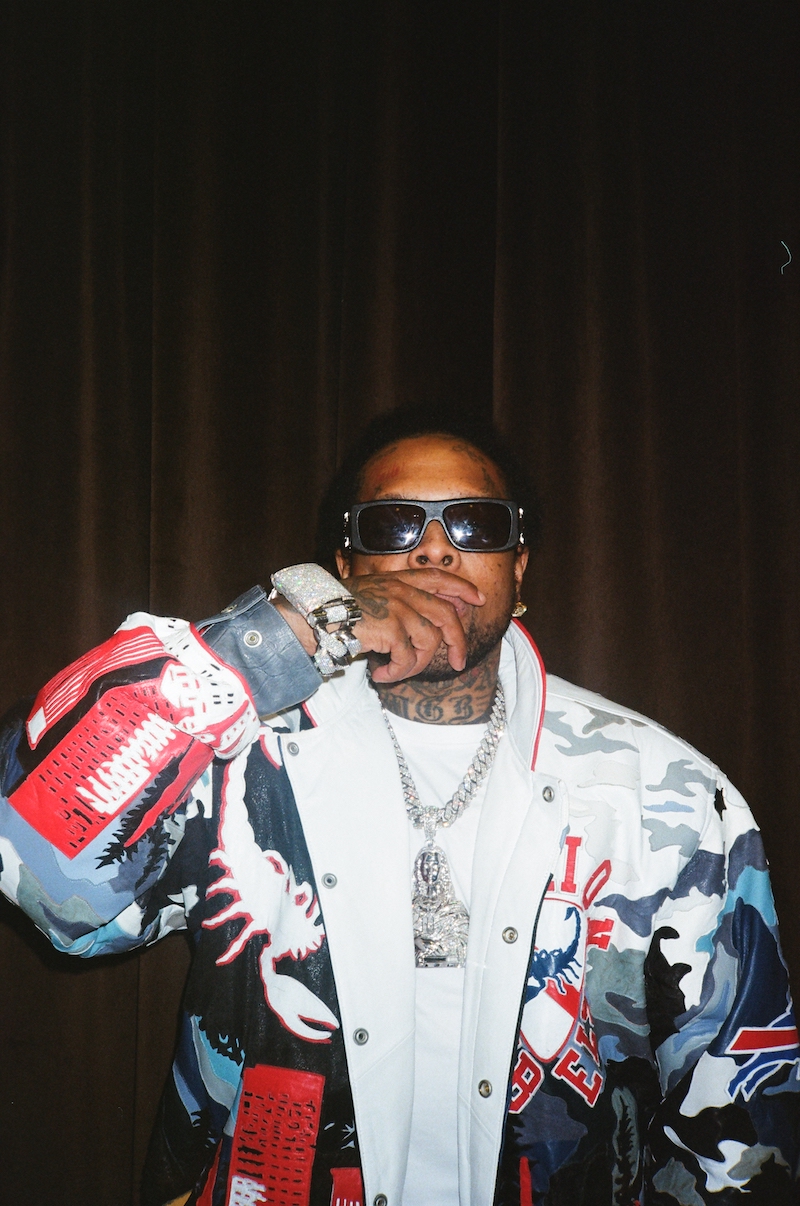

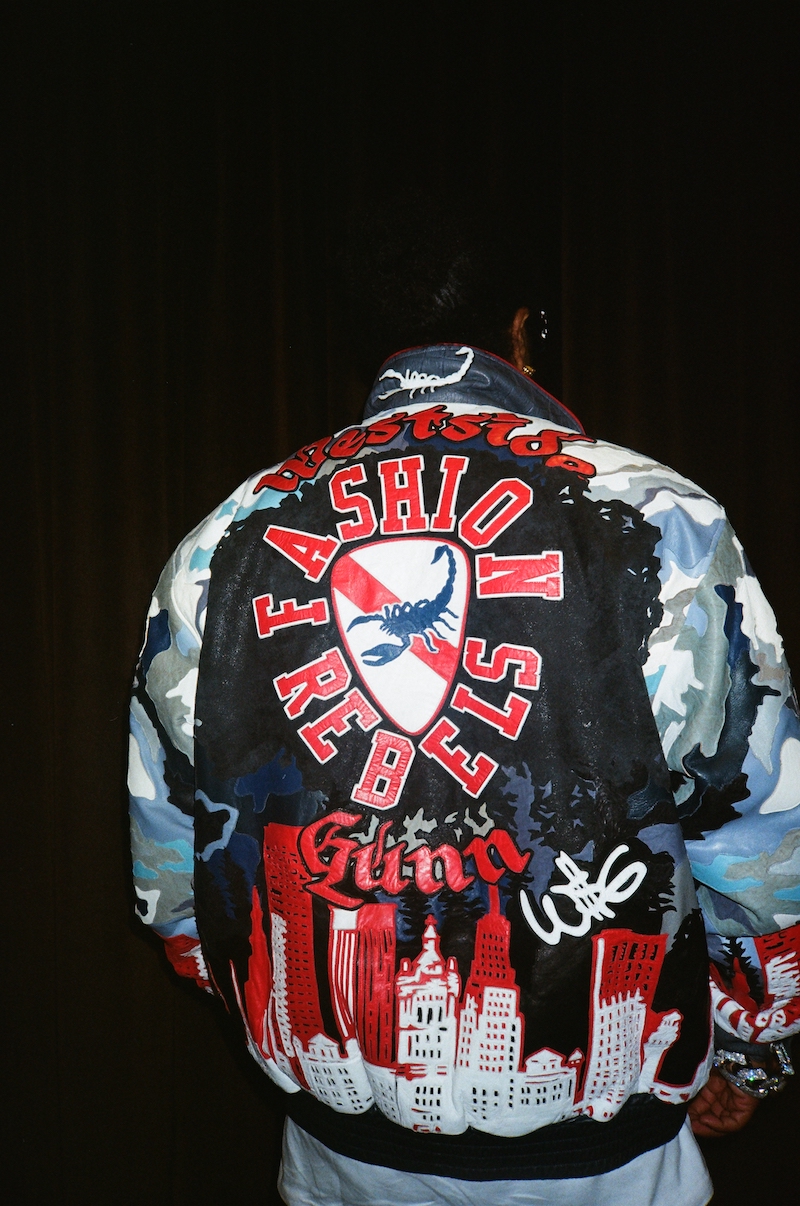

Last Thursday night, Gunn hosted a listening party at Goldbar — a venue that perfectly matched the theme of the album: luxury. Here, we saw some familiar faces who popped out to support the rapper, such as Tremaine Emory, Benny the Butcher, and more.

office sat down with Gunn to discuss the making of And Then You Pray For Me, his end to studio albums, and what’s next for the Buffalo, New York rapper.

How was the listening party for you, and what’s been the feedback so far?

The listening party was dope because I never have listening parties. I never have parties at all. It was cool to see a lot of my peers, day-one-supporters, and family come out…It was super dope. I want you to hear the album all the way through and pay attention to the art.

Where was the album created?

It was done in Paris, Copenhagen, Denmark, and so many different parts of the world. I went to Athens and Santorini, Greece. I was just in the zone. Paris Fashion Week inspired me in January, like the first time I went in January 2020 with Virgil. I had that same feeling again. It was my first time since Pray for Paris. Not to sound corny, but it was the spirit of Virgil. He wasn’t there physically but spiritually. Let’s finish what we started.

Does scenery give you a lot of inspiration?

For sure. That was one of the top reasons why I did Pray for Paris. Leaving the country and going to a place like Paris is mind-blowing because I’m from East Side Buffalo. A lot of people will never see the Eiffel Tower in their life.

I’m hearing that this is your last album. Is that true?

It’s my last album as far as making over 20 songs, 15 songs of a full-body album. I’m more into making a song today and dropping it tomorrow like the Soundcloud, raw Griselda days. Instead of focusing on an album, only dropping once a year, and putting all of that energy into trying to present one project, I’m like fuck that. I might make a song and drop it tomorrow, even though my album just came out. I finally have people’s attention. Some people love it, some people hate it. They don’t even see the bigger picture, they’re just worried about today.

What does this mean for Griselda?

I’m never going to stop curating. That’s the thing about my team. If I call Conway the machine right now and say, ‘Pack your bags, we’re going to Poland for a month and about to record,’ he’ll be like, ‘Let’s go.’ Griselda is a family. When you sign to Griselda Records, it doesn’t mean you’re signing your life away to Westside Gunn; it means you’re my family.

I want to talk about the album cover of Caravaggio’s The Entombment of Christ. The late Virgil Abloh created it?

As soon as I was done with Pray for Paris, V told me to send a picture of all my chains individually. I laid my chains out, and he started sending me different art pieces with the chains on. At first, I wanted this to be kind of a trilogy series and have Mona Lisa represent the Pray for Paris series. I got the blessing from his family and everyone involved. Unfortunately, he passed. When I was going to do part two, I didn’t have the energy to do it. The time wasn’t right. I felt weird even trying to do it, it wasn’t even a thought. I let it (the covers) breathe for a while and get some air. Like I said, once fashion week came around this time, it felt like the time. He (Abloh) sent me there again.

I think it’s important for Black people to travel the world, especially where they’re least expected.

Especially because nobody’s even seen a motherfucker from East Side Buffalo. We’re a different breed. We never get respected because we’ve always been in no man’s land. I never took offense to it. I’m just going to work harder than everybody I know and put my city on – and I accomplished that.

Because Pray for Paris and And Then You Pray For Me albums are similar, are the albums correlated?

This is the sequel, but I didn’t want to call it Pray for Paris Part II. When I made Hitler Wears Hermes Part II, I made a song with Eric B., and in the song, I say, ‘Pray for Paris, then you pray for me.’ This was a line I said a decade ago.

There is an interlude in the album of Tyler, the Creator, saying you’re one of the reasons he wants to continue rapping. How does that make you feel?

It’s a blessing because that’s what I’m here for. Some people only come into this shit for money and with hidden agendas. I came into this shit so pure, I always did it my way. I’ve never compromised my art. I always stuck to my heart. I basically controlled my own destiny all the way through.

Now that you’re over long studio albums, what’s next for Westside Gunn?

I’m excited to just watch my kids grow. I have a daughter that’s only two and a son that’s four. This is the most I’ve ever been away from home, but they came with me everywhere. I’m not the only one who went to the Pyramids; they rode a camel, too. Now, I’m just gonna have fun. There’s no more pressure on me to do full albums. I can just give you art when I want, how I want, and when I want. I think it’s going to be even better. You’re going to get a better version of Westside Gunn. Long live Michelle, long live Virgil.

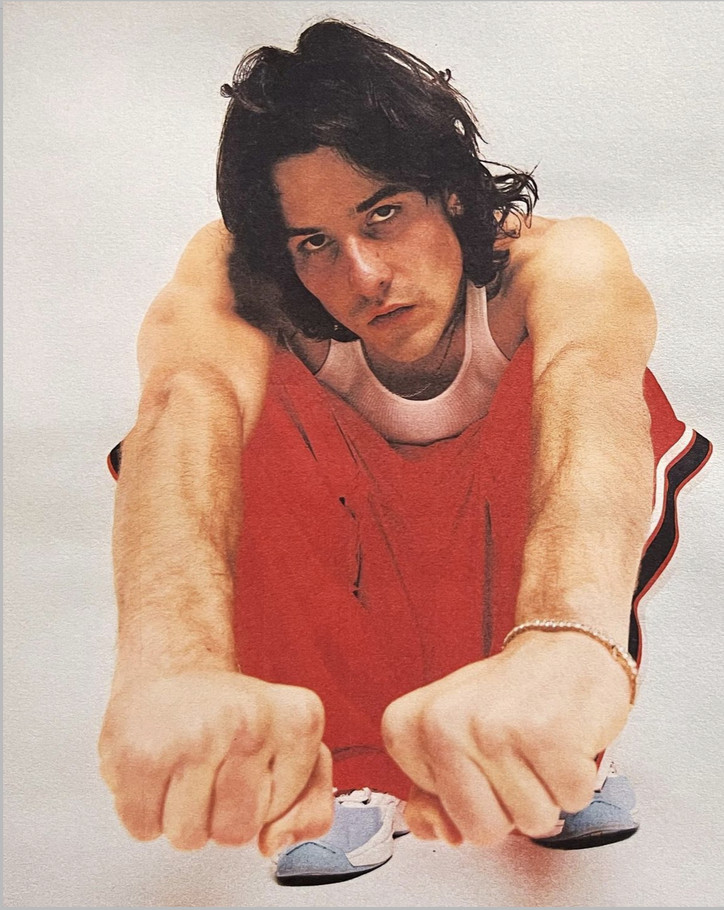

After teaching himself the music and songwriting process from scratch, Guy released his debut project Who’s Taken Time?! Act I — a reflection of the self. Now he brings a new layer to his artistry with the project’s B-side, Who’s Taken Time?! Act II — a departure from the “I” and newfound focus on the “we.” office sat down with Guy ahead of his first headline show in New York City to peel back the layers of his artistry, diving into Philadelphia’s influence on his sound and learning to embrace vulnerability.

Starting at the beginning, we grew up in the same place and I feel like a lot of your craft now is shaped by that upbringing. How did growing up in Philly shape your creative outlook?

When I first started to really think that music was the thing for me, I had a lot of resistance to even thinking about Philadelphia in the context of my creative process and my music. I think I felt a lot of resentment towards where we grew up. So I kind of spent my first year in LA being very ego-driven. It wasn't until I put out the first part of this larger Who’s Taken' Time?! Act I that I realized everything was really coming from that place. I was reflecting on relationships that I had sort of fallen out of touch with and, generally, that separation from East Coast and West Coast. And I think through starting to write a lot of records with that lens, I realized that I was totally wrong and I was writing from a very dark place. It was a very self-centered, self-focused place. There were a few big moments since then, like going back East and reconnecting with my brother, that changed my perspective. We had gone to the Brandywine River back in West Chester and had a day. It was fall, so the water was freezing cold, but it was this really amazing moment. This is my big brother and I hadn't seen him for almost two years. And also that river carried all these memories to us from when we were younger — but it was a place that we never really thought about as this sacred, special place. But when we were there together, we felt like there was some sort of — it sounds crazy — but some spirit amongst us. It brought me close to the land that we were raised on and it was a crazy turning point for me. I kind of switched up my whole flow. I scrapped the back half of the project and I rewrote everything after that journey back home.

And these new songs on Act II are all about community. They're about the ‘we;’ they're about togetherness. It was telling stories that weren't just about myself or my struggle, whatever that is. It was an appreciation for everyone that's there for me in my life. And I think also sort of a quest for community, bringing people in and stepping outta myself. I also just think it’s cool to care about things. I mean, I always cared and had so much love for home, but I think I just was able to finally remove the resentment and realize that this place is actually so important for me and my growth and it's not something that I want to really erase from my past.

If you could go back and tell high school Noah anything, given your accomplishments now, what advice would you give him?

I think that I was very scared. I felt like there was only one practical path and that was just getting the four-year degree and not really leaving a lot of time to reflect on what I really wanted to do. I think it was really hard for me to be fearless about being vulnerable. I was so afraid of being vulnerable and sensitive around other dudes in our grade. You know, there were social structures at our school, at least to me, in my head. I think I had a hard time relating to that. So I would just tell him to just be very fearless about the things he loved. I always loved music. I always loved film and the intersection of those two things. And I always loved singing. And I think towards the end of high school, I got a bit more open to kind of embracing those things.

But there were so many years where I held back when I was really pushing for basketball. That was, initially, the thing I wanted to try to do in college. I always think back to this instance. I was posting these Vines of me singing and — this is so crazy that I'm telling you this story. But I was thinking about it the other day; I had posted a Vine beatboxing and then I did a little singing moment. It was this cute little vibe. And then my basketball team saw it when we were traveling for an away game and I just got roasted into oblivion. I was just like, 'Okay, no music.' I was beatboxing for the acapella club though, 'cause that was still kind of 'cool.' That was sort of permissible. But it took me a really long time to break that circuitry. I think it's about just being fearless with my belief system and not being afraid to be a vulnerable dude. Being vulnerable and being sensitive doesn't make you weak. I think that's being a man. That was also a lot of what this project was for me — thinking about my masculinity in those terms as well.

When you're 16, it just seems, I guess at the moment, so much cooler to be like everyone else. And sharing music, sharing writing, sharing anything that is an art is really personal. I think that when you're that age, you don't want to let people see those parts of you. And then you get older and realize it's so much cooler not to be like anyone else.

For sure. And now that I've had time to sort of reflect on it, I've also found so much love in my heart for everyone we grew up with. I see them on my timeline and it makes my day to see what everyone is doing now. So I think it's also recognizing that this path isn't this miraculous thing that I'm doing. It was what I was supposed to do. You're supposed to create and make art and do that to the best of your ability, but there are also really incredible things that other people are doing too. We're all just figuring it out.

How did it feel to record your debut EP from your childhood bedroom, after experiencing such a life transition and returning back to where it all started? That was in 2021 — how have you changed since then?

It was such a wild experience. So I was going to NYU and then when everything went online, I just couldn't justify paying an NYU tuition. And then there was an opportunity for work so I went home. I was very fearful of fully committing to music. But through this bizarre kind of silver lining of the pandemic, it sort of forced that hand for me. And I went back home 'cause I didn't have anything to do, like all of us. Every day I had this setup — and this is such a privilege, right? The ability to have my parents host me and support this new creative thing. I'd never recorded myself before. I had no equipment. I'm like a grandpa with technology, so I had to learn the bare essentials of how to just get my voice on a microphone and I was using Garage Band. I had this $15 Walmart microphone and I wasn't taking it seriously — it wasn't a very professional sound. But I was really able to learn a lot about songwriting. And I think I started to find my voice through that project. It was four records I had made over a span of maybe three or four months before moving to LA.

That was also around a time when I really started to do a lot of music listening as well. Music from Philadelphia. I really fell into this whole deep dive during that year. Philly’s music history is just so rich and I had always grown up listening to Motown and loving it. But I didn't even really know where these songs and these sounds came from. I had gone to a bunch of record shops in Philadelphia during that time and I would crate dig and find things that were inspiring to me. Hip-hop became a huge thing for me as well. I was studying a lot of East Coast hip hop and also a lot of Americana and folk music that came from Philadelphia. For instance, there's this one artist who has really bled into my whole listening experience and the inspiration for this whole Act II. Jim Croce was this Americana, folk singer and songwriter. An absolute legend that has some of the craziest hits — if you heard a Jim Croce song, you'd know. But he grew up right down the road; he had a house on the Brandywine. I kind of became a music historian over those months and fell in love with Philly music and Philly music history. I think that became the foundation of what my sound is.

Your sound is a unique blend of R&B, hip-hop, and soul. Who were some of the earliest artists you remember filling your playlists with?

The first CD I ever bought was this album called The Ecstatic by Mos Def. Mos Def is one of my favorite rappers of all time. I was very curious about music discovery from a really young age; I got that in the fourth grade. That album really shaped me a lot. But really the first music I listened to was my dad's Motown's greatest hit CD — it got stuck in his jeep when I was a kid. He was so resistant to getting a new car [laugh] so for pretty much the first 10 years of my childhood, it was the only thing we were listening to every time we'd go in the car. It was The Temptations, Marvin Gaye, just a lot of these classic soulful pop records from the sixties and seventies. That's the music that I always come back to. So most consistently, it's these songs that were super soulful and also just very catchy. But they were presented in a very creative way — with the vocal layering and the dynamics of it all. That all led me to think today, 'How can I make something that's a little bit more left of field, but that still has this sort of universality?'

What did you feel you were uncovering about yourself through that process of writing and creating Act I?

I started to notice, as I was moving through creating these songs, that I'm pretty good at self-isolating and cutting myself off from people. People that maybe really love me and want to be there to support me. But, for some reason, I was very resistant to that. And, at the time, I also thought that part of the craft of music-making was this idea of struggle. That starving artist mentality that I needed to adapt at all times in order to make the best music. I think I thought that music couldn't really spawn from a happy place, at least for me. I needed to struggle through life in order to find those golden nuggets. So I started to catch myself in the act of doing that. I met a lot of incredible people over my first year in LA — but it definitely was really hard. I was working multiple jobs and certainly coming to terms with the fact that this music stuff is not easy. I didn't have rose-tinted glasses anymore about it. I realized that this is a lot of hustle and definitely not for the faint of heart. And through making those songs, I kind of started to push away from people. I had a hard time really holding on to connections and I was spending a lot of time on my own. I got to this point where I felt like the best music needed more than just me coming in and servicing the records. I needed to tell stories that weren't so heavily inward-facing and brooding.

Tell me about one of the hardest songs to write from Act I — how did it feel to confront certain emotions in that process and really create professionally for the first time?

I'd say probably the song, 'Small Talk Carolina.' It was the last song I made for the project, but it was sort of my first moment where I was speaking on and speaking directly to Philadelphia, folks back home, and my feelings toward those things. Carolina was this fake muse that represented a lot of friends — I had a couple of people in mind, specifically, from my childhood. I used the Brandywine as this motif through it all. This idea of purifying and washing away. It was really difficult for me to write. It brought forth stories that were uncomfortable for me to talk and think about. But it became this turning point. Once I finished up the record, I was like, 'Okay, I think there's something to this.' It was my first moment of really speaking about anything beyond just myself. I was talking about other people. I was telling the story of what a privilege it is for me to be out here talking about myself and this sort of ego journey that I experienced. There are people everywhere who may feel the same way I did and want to express themselves creatively. But they may not have the means to get out and create and explore. It really comes down to what a privilege it is to be an artist. Or to have the ability to at least start and make this journey happen for yourself. So that was the first moment where I really started to think about community in those terms. I woke myself up from the idea that the world was against me.

I think a lot of artists eventually have that discomforting confrontation. It's this feeling that the work won't resonate with people unless it's coming from this deeply emotional or pity-invoking place. But you needed to go through the process of making Act I to come to that revelation. You mentioned that Act I was more of a meditation of the self, while your recently released Who’s Taken Time?! Act II is more collaborative. Tell me about some of the collaborations on this project and what they mean to you.

After I wrapped up Act I, there was a two-month in-between period where I made the decision that the five other songs that I thought were gonna be sort of the B-side of this project, didn't represent the story I wanted to tell anymore. It was a perspective change, even outside of the music, just generally in life. And I'm fortunate that my closest collaborator and executive producer is like my brother. I work on all my stuff very intimately with my roommate Choob — Devon is his name. We first met online and he was the first person to send me a beat pack. So I went to him first and I was like, 'Yo, I really feel like we need to refocus our efforts here and try to find some new songs to make because I just feel very exhausted by the ones we have.' I thought there was a better story to tell.

So we went up north to this little cabin in this town called Lake Arrowhead. We needed some sort of separator and we were there for about a month. We started inviting friends up from Los Angeles — session instrumentalists, other artists, my friend Amaria, Braxton, who's this saxophonist and one of my heroes. He's an incredible jazz musician. They all came up, even folks that weren't really specifically working on the records, just people to spend time with. And that became the overall ethos of the project — it became very clear that we wanted to do something that was very community-driven. And we wanted the records to sound that way, so we really leaned into a very live and raw sound. We tried to leave things very unadulterated where there's not a lot of reverb. There's not a lot of things that my vocals are hiding behind. Act I was so busy. So I think taking time and holding space for friendship and just slowing things down during our time in Arrowhead, also bled into the song structure generally too. We just let the moment breathe. So I genuinely think that the spirit of that experience, on a friendship level and on a human level, that exactly translated to what the records became.

I feel like when you take on a creative undertaking, you become so prone to doing so many things at once or trying to supplement one thing with another. And it's just interesting that you expressed how things became fuller when you slowed down.

Do you feel like you're able to still create space to be mindful and present and slow down? Or do you think that is something you wrestle with? Because for me, it's still a journey. There's a lot of growth there that needs to be done.

I feel the same way. I think it's really hard. I'm not really thinking about that first achievement because I'm already thinking 20 steps ahead.

That's the whole crux of what the project was. Taking time to appreciate your accolades or the milestone moments you're reaching. It was like, 'How are you taking time to actually process what's going on?' It's so hard when the finish line is always moving for us, you know? Which I'm sure it is for everyone — it's a universal experience — but I think you definitely feel that way when you're doing something that's a little bit more unconventional or creative.

This industry just breeds a lot of comparison. So I think that's also part of it and part of being present. It's near impossible to do so when you're also focusing on other people, but it's also near impossible not to do that as well.

I think that the ultimate lesson is that no journey is replicable. You have to just be so dauntless and recognize that my journey is my journey and however that shakes down, that's what it's gonna be, you know? And I'm gonna just keep putting the work in and that's really all you can do. I think we do our best work when we're feeling more and thinking less.

You studied film at a point in time, which explains your heavily artistic and narrative-driven visuals. How do these other elements, like your artistic persona and even your personal street style, shape you as an artist — especially in this social-media-driven era?

The bane of my existence has been short-form content. I think we're in such a bizarre world right now where all these new artists, including myself, are coming up in the TikTok era. But prior to this, there was the blog era. There was SoundCloud — but I think it was very show, not tell. Now it's very tell, don't show — and tell everything to everyone. Tell them daily and find the easiest, quickest, most clickable way to do so. And I think when you're the one doing all of the talking, you don't really leave much for yourself as the artist. Some of that magic and some of that allure kind of goes away. That's why I think it's so hard to build a brand in this TikTok era — at least it's been challenging for me. Of course, there are ways to do it and it's become a necessary tool. I'm always thinking, 'How can I use this to my benefit?' I don't have the answers to that yet, but for me, I need to still be very committed to not sensationalizing my music. I just like the idea of making a really cool music video even though it's not really an era for music videos right now because I don't think the industry really rewards a great music video in the way we used to. But for your core fans who really love your music, that still matters. The ability to pair a visual with the audio experience — those things have always been two-pronged for me. I grew up loving film. That was kind of my first joy but I didn't really take a lot of time to share those interests with other people.

On that note, if there was a movie about you, what would it be called and who would you want to play you?

Well, recently I've been trying to get into my acting bag. I've got a couple of scripts I've been reading. But I think a throwback rom-com A-lister would be cool. Like Paul Rudd. I'm a pretty goofy, awkward person and I think he would translate that well. In terms of the name, I think I would just call it Who's Taken' Time?!