The Triumphant TOKiMONSTA

For her latest LP, Oasis Nocturno, Lee applied these principles in every way she could; it’s a highly meticulous project with many interconnected aesthetics and themes, and Lee made sure that she exercised her creative agency in everything from the mix to the show’s lighting set up. The result is a clear and focused album that exhibits all of Lee’s influences.

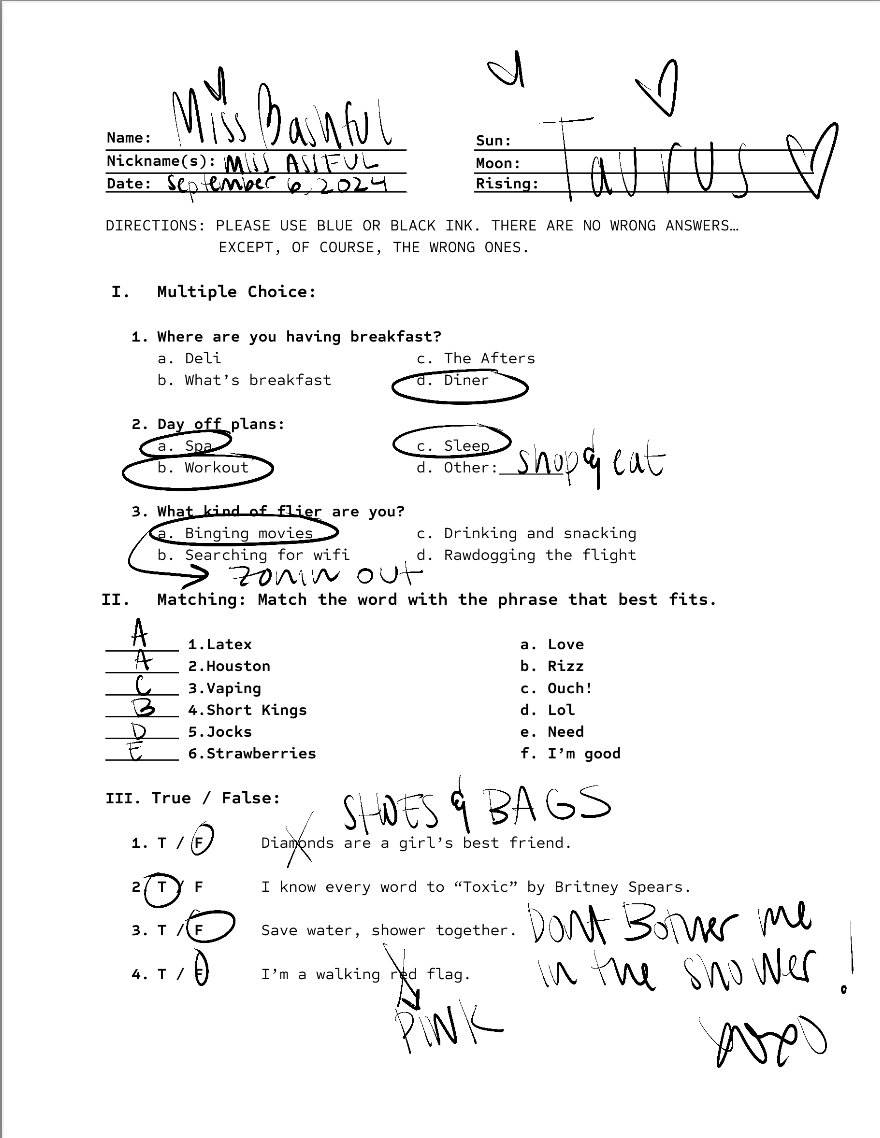

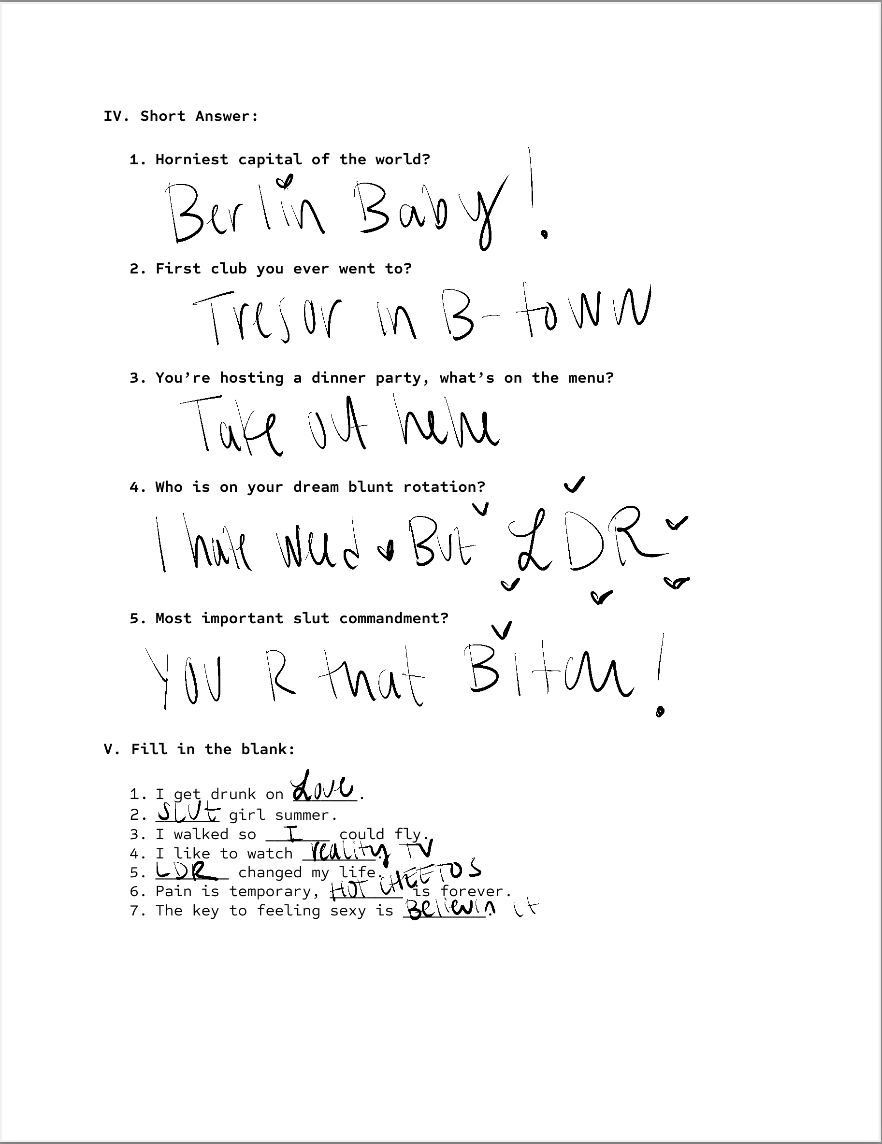

Lee’s sound is a nebulous mix of hip hop, EDM, and oddly enough, classical music; she’s very much a product of her music library. Born and raised in LA to an immigrant family, her life at home was contrasted with what she encountered while frequenting the hip hop clubs in Central: Classical piano lessons meet Westside Connection. She accepted and adopted everything that caught her attention without judgment.

After the release of her latest project, Lee hopped on the phone with office to talk about the time she spent as part of the Los Angeles “Beat Scene,” her narrative vision when it comes to her live performances, and the ways in which she’s staying connected with fans during quarantine.

What was your experience of the rave culture in the early 2000s? I know in the 90s, the scene exploded in LA—did you come on during the tail end of that wave?

By the time I had started going to raves, it had already entered a phase where it had massive festivals. It was different than the culture in the 90s, from what I've heard from my friends who were around earlier. But very different than what it is now, too. I think it was kind of on its way to being as massive as it is now, but maybe not as built into normal pop culture. Like now, what is a rave? Is it a club? Is it something you go on a Friday night? Is it really a "rave" rave like what you would've seen in the 90s in America, which is probably more akin to what a rave is in Europe.

I participated in it, but I feel like I'm more active in it now as a musician. I was mostly in the rap and hip hop scene in LA—a lot of electronic and experimental rap and hip hop.

Right. You were part of Project Blowed for a bit. What were some of your first performances there like?

Project Blowed has been around for a really long time; it's kind of the birthplace of freestyle rap, in that specific style. It was around many generations before I started going. When I went, I had a friend who brought me there; it was around Limerick Park, which is Central LA, and not a place where there are a lot of young asian girls trying to play beats, so I had to really earn the respect of the people who've been there for so long and who were such a part of this deep-rooted rap and hip hop culture in LA. I remember going, the first time, and I had a CD with some beats on it that I was going to play at a beat cypher. During a beat cypher you just go up and play beats and everyone is like, "Wow. That's a really fire beat." You just stand up there, bobbing your head, not really doing anything, because someone else is playing the CD with your beat. So, I go there, and obviously I'm a minority, but I start playing these beats and people start giving me these sneers like, "What's she going to do? This is going to be sad," or whatever their expectations were of me. But I played some beats, and everyone was pleasantly surprised. You could see that shift in their facial expressions, from doubt to a humble nod that this isn't completely bullshit and she's actually good at what she does.

From Project Blowed, I started going to Low End Theory. They were happening around the same time, but Low End Theory spoke to me more. That was a club night that happened every Wednesday that happened in Lincoln Heights, just north of Chinatown. That's really where my roots started. I got my chops at Low End Theory and really became part of a community of other artists. Unlike Project Blowed, Low End Theory wasn't rap-centric. Low End Theory was very much focused around producers and DJs. I think one of the most notable guys to come out of the scene was probably Flying Lotus. There was a group of us who made instrumental rap beats, and not typical ones. They tended to have a lot more electronic elements than traditional rap beats. That was what ended up being called the "Beat Scene" of the late 2010s. That was really the genesis of my career as a musician.

But you went into video-game design first, right?

Yes. So, right after graduating college, I was like, "What's a cool job that's respectable that my mom will be okay with?" So I went straight into this company that published video games. I liked the environment, the stuff there was cool, and I could tell my mom, "Yeah, I work in business," yet be around a lot of cool, chill, gamer-type people.

What was the moment that you decided to go back to music?

Music was a hobby this entire time, throughout college, and even when I got a job. There was just no part of me that it was practical by any means to actually pursue music. I think it was just the way I was raised; I was raised in a manner where it was very clear to me that my mom came to America and worked really hard to provide this life for me as an immigrant, so that I could go and build a better life for myself, a stable career that has longevity and security—I'm sure you've heard this, with lots of children of immigrants being a doctor, a lawyer, an engineer, something like that. So that was me being in an industry that was kind of cool, but also was business development, licensing, and all of that. Though I always had music as a hobby. I remember I would come into work falling asleep at my desk because I would be staying up so late going to these music nights, playing beats. But it was when I got laid off from my job that I decided to pursue music full time. I could've probably decided to pursue it sooner, but it just seemed so risky to me, and I didn't want to put that much pressure on a passion of mine. I've seen it with others; once their passion becomes their paycheck, they become jaded and lose that love for it. And you know, I just resisted it for so long. I make music in such a niche scene, there wasn't any "big" yet in my scene. Half the people in the world don't know this genre of music.

When I got laid off, I told my mom, "If you could just give me a year to see if this music thing works, if you could just give me your blessing, be cool and don't bitch at me for a year about doing this, then if it works, it works. If it doesn't, I'll go back to grad school." Nothing lights the fire under your ass more than moving back in with your parents. I was very motivated to make it work. And within that year, I was able to do it full-time. I went from getting laid off to being able to sustain myself that following year. Eventually, people started asking me if I wanted to go on tour. These small venues in Europe were saying, "Please let us know if you come to Europe. We'd love to have you play our venue." So I sent myself to Europe. I had never been there—I had never been to a foreign country before—but I went and played Greece, London, Amsterdam, all these places on my own accord. It's crazy to think about it now. I don't think I have the guts to do it now, but I did then and it worked out really well.

What attracted you to rap and hip hop when you were so young?

You know, I really have no idea. Thinking back, I was a little 4'5" asian girl in fifth grade listening to gangsta rap—it's pretty absurd. I've just always been a fan. I think so much of it has to do with the beats themselves, the movement, the rhythm. But also how heavy it was, in terms of the sonics and lyrics; the visceral feeling of what people were portraying at the time. The stories had an essence that called to me, and I just wanted to be a part of it. Especially the fact that it wasn't most revered genre of music. At the time, "Bad people listened to rap music." And I liked that. I liked that it was different. It's the same reason I like listening to Aphex Twin, or noise, or Health. Something about the unconventional makes it more real to me. I love pop music too. I coulda been listening to Backstreet Boys back to back with Dr. Dre.

As someone who sits at the intersection of multiple genres, how would you describe yourself as an artist? Is there one genre that you feel defines you better than others?

I would say that as an artist, I'm just a culmination of all my influences. I'm a product of all the things I've listened to my entire life. It's just my taste and approach that defines my music, and I want to always be aware that listening to music has a profound impact. I'm the kind of musician who loves consuming music, though every musician is different. Some are like, "I just do what I do, and I don't listen to anyone else." That's what defines them, but for me, I'm so excited by new music, old music, weird stuff, conventional stuff. As a kid I would listen to Square Pusher and Blink182 side by side and think that was totally fine. At that time, I don't think it was that common for kids to be that diverse in their music tastes. It was like, "I'm just a kid who listens to rap, and I'm just a skater kid who listens to rock." There was more of a separation, but I have never been that way. I grew up listening to Schubert, and Bach, and Mozart too. For me, today, it's just hard to define myself by one genre. But, to use the most genre-umbrella term, I would say I exist somewhere beneath electronic music.

You've likened yourself to a conductor when you perform live, and I know you also studied classical piano when you were younger. Do you think your time studying classical music has influenced how you arrange and compose your DJ sets?

One hundred-percent. I think that classical music can vary in how things are sequenced, how the songs meander and exist. But for me, I've always loved the story telling that exists within a classical piece. They can be really long—maybe they have areas that repeat twice and go further and develop. It's kind of like “The Hero's Journey.” You hear that a lot in classical music. You have a melody that goes through these twists and turns, and you can hear it escalate, and you can hear conflict and resolution. I really like when my sets are like that as well, where you can have these moments where you're existing, but then you have tension—and not just tension like a "rise" and a "drop," but the greater story you're trying to tell in your set. This is going to sound corny, but a lot of times I ask my audience, "Hey, are you guys ready to go on a little journey with me?" This is going to be a trip, and if you're expecting to hear the same type of music and the same tempo for the next hour and a half, you're going to be disappointed—I don't say all that to them, but they will be disappointed.

When I DJ and when I perform, it's across all genres, all tempos, all moods. But I try to make it as seamless as possible, so you feel like you understand that you're about to enter a different phase of the set. It's taken many years, and it's weirded out many people along the way, but I think people kind of get it now and enjoy the variety that exists in my performances.

I noticed that in lieu of a tour, you've done live performances online? Considering everything you just said, it must have felt a lot different performing for a virtual audience.

You know, it's so interesting because there's no immediate feedback. So I'm just hoping that whatever I do works. I can't change it for them; I can't tell if they like it. But, it's been great. It's been the most amazing boost in confidence actually, to do these blindly and see how wonderful the reactions are. When you look at almost fifty-thousand people watching one of my streams, it's like, "Wow. That's more than a festival." fifty-thousand people watching something concurrently for an hour is amazing. It's me playing music that I've always enjoyed playing and seeing everyone go, "Who knew she was this good?" And also me being like, "Oh wow. Who knew I was this good?" Because I hadn't seen that kind of feedback written down in a chat. Oh, but also tons of people say terrible things as well. I have this thing where I really try not to read YouTube comments because for as many good things, there is always that one-percent that says something terrible that will trump all the nice stuff. If I see a lot of heart emojis, that's good enough for me. I try not to read the text.

The devil lives in YouTube's comment's section.

More so than anywhere else, huh? Maybe Twitch. Twitch comments are pretty bad too. But yes, I've been pleasantly surprised about the concerts. I've never been one to expose myself in that way. The occasional selfie and instagram video—I'm guilty of doing those, but I've never posted entire DJ sets online. It was something I initially did because of necessity. None of these big festivals were happening; my entire tour was canceled. I asked myself, "How do I reach people right now and share with them this album that had just come out in the midst of this?" I was reluctant at first, because I felt like I was cheapening my performances by putting them online, but it turns out it was a great thing to do. Now I'm more connected to people, and more people are seeing these performances than would have if I went on tour, and there's a beauty in that.

Are there other ways you're trying to connect with your fans remotely?

Oh, yeah actually—I feel like I got caught up in doing all these things I didn't want to do, but they ended up being good decisions. I host a weekly streaming show called, The Lost Resort, and basically I patch in artists every week to talk about how they're dealing with quarantine. We share five or so songs that we’re listening to, and then my favorite part is we eat. Remotely, we all order takeout from our local restaurants to support them—or, lots of artists have been cooking for themselves, which has also been super dope to see. And it's been going really well! I've never thought of myself as someone with a host personality, but it's been pretty fun. Also, drinking on it’s been fun, too [laughs].

Now, I’m sure you get asked about this a lot, but in 2015 you found out you had this really rare brain disease called Moyamoya and shortly after underwent brain surgery. Subsequently, you lost your speech, significant motor skills, and your ability to hear and make music. Obviously, you’ve recovered. But how long did it take for you to be back at 100%?

Two to three months. The brain is incredibly plastic. I definitely went through something traumatic, but as crazy as it sounds, people go through far worse. It's not a contest, by any means; it was just a humbling experience, and I can't imagine what other people have gone through with more severe symptoms. The one benefit of being able to get through it allowed me to really understand the process I was going though. Even at the point when I presented as okay, I really wasn't. Two months in, I could go meet people again, but I don't think people realized that I still couldn't speak—at least not at the level that I was speaking at before the surgery. It was just really easy for me to hide it. I think that that experience has defined me to some degree, and I've been asked about it before, like, "How do you feel about being the artist that's gone through that?" But I don't think that there's any problem. I take ownership, and I'm quite proud of where I am today. If I can share the story with more people and give them any glimmer of hope that they can make it through a difficult situation that they've been in, then that's fine.

I'm sure it was a period of immense self-reflection for you.

I think when I was recovering, I had moments where I was like, "This fucking sucks," but really I was just in survival mode. Every single day I needed to improve. I needed to walk more, I needed to talk, I needed to get myself a few paces forward so I could see progress. That's where I got my motivation.

Really, the self-reflection the year-and-a-half later when I started telling people about it. When I went through that healing process, I didn't tell anyone what I went through so I didn't have to talk about it. No one asked me, "Jen, how're doing? How've you been?" Less than ten people knew what I was going through—that includes my family and my friends. Everyone else just hadn't seen me for a couple months. But when I came out with Le Rouge, which is my previous album, it was really important for me to share the story behind that album because the entire album was made post-surgery. And once I had to start talking to people about it, like the Chicago Tribune, the New York Times, when people started asking me all these questions, I started realizing that there were a lot of emotions I hadn't dealt with. I was getting choked up talking about my experience. At that time, I realized that I didn't deal with the emotions I had gone through in a healthy way. I had just prospered and pushed it behind me. I just thought, "I never have to deal with this again." That's the way I dealt with the emotional trauma of that whole experience. But now, after being more reflective and having talked about what I went through over and over and over again, I've been given more peace. It's almost like the press was a form of therapy for me. Talking about it turned out to be this beautiful progression for me. To be honest, if I start talking about certain components in great detail, I will most likely still get choked up. I have good days and bad days. But it's okay, I'm glad that I'm here, that I can talk to you on the phone—I can't go outside, but at least I'm alive [laughs].

It's a good time to be counting our blessings. So, what was the motivation for your newest album Oasis Nocturno?

I really wanted to create a body of work that was more concise and more put together than anything else I've made in the past. I wanted to make sure that a whole world was coming out of this, and by that I mean, there is the music, but there's also the artwork associated with that, the live shows associated with that, the music videos associated with that. I really wanted to create an experience where people can see the consistency in the aesthetic and sound—and what would've been the live experience. I just wanted the ability to have control over everything I created. This is the sound I wanted, the aesthetic I was going for. The music all has a specific sound signature and is mixed in a certain way. All the songs have a similar thread running through them. I'm really bummed that I can't do the live show. But, I'm hopeful and have a positive outlook; we will party again at some point.

How did you go about curating the list of collaborators on this album?

Man, I feel like I just got so lucky this time around. Every single artist that you see featured is someone who I really respect and am excited about. I mentioned earlier that I'm a big consumer of music as well, and they're all artists that are up and coming, who are doing things. I think I was in the studio for all of the sessions. We were together and it was sincere. I feel like when you make music with another person, and there's a clear connection between you and that person which is good, it shows in the music. Many times, songs nowadays are made over the internet, without ever meeting the person. There's no reporte. When there's something more aligned between the artists, it just shows, and that's what this album was.

These are just artists who I like, and I asked my manager, "Hey Louis, can we reach out to them and just see if they want to work with me on a track?" I had a surprising amount of responses where they were like, "Yeah we'd love to support you." A good example is EarthGang. They were the ones I was the most surprised about. I had no idea that they'd know who I am, but when I met WowGr8 in the session, he was like, "Hey, your song ["Fried for the Night"] was my favorite song to smoke weed to in high school." That was just really cool to hear. Knowing that my music has had an impact on artists who are really successful today is pretty neat.