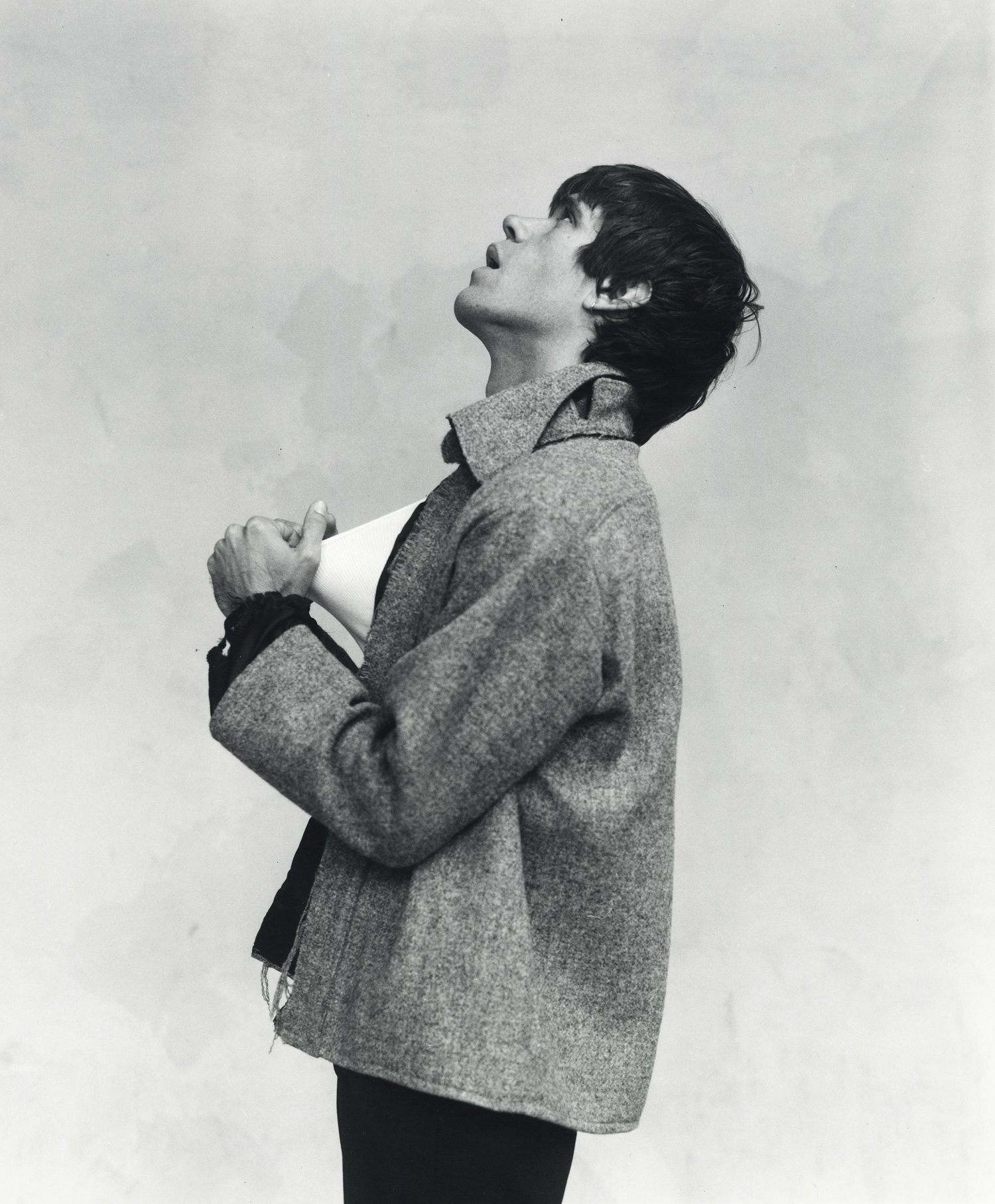

Uncomfortable Listening

BBC Radio 6’s Mary Anne Hobbs called Religious Equipment “void core.” It’s abrasive and all-consuming, disarming you and forcing your gaze inward. That’s the beauty of noise music, Culver insists. “I just wanted to make a record that has no meaning,” he says. And in meaning nothing, it can mean everything. It’s not supposed to be familiar. You don’t even have to like it. It’s meant to provoke, to make you think in a way you haven’t yet.

Maybe listen to the record before you read this or do your research on Culver. You can enjoy it or despise it before you understand his history and his context. Then do your reading and try again. See if it changes form. It’s okay to love art for reasons the artist never intended. And it’s okay to hate art before you know the artist. Anyone who says otherwise is being pretentious and probably regurgitating a review from an equally pretentious critic. Culver values your honest reaction above all else. DM him that the record made you take a pair of scissors to your headphones because you couldn’t bear another second of it, or that it inspired you to paint a tree. He’ll probably post a screenshot of your message for an Instagram discussion forum about the meaning of art today.

Megan Hullander — Last we spoke, you said you’d maybe adopt an alias once your music got abstract enough. What brought it to that point?

Richie Culver — I think it was more for admin in my head, for keeping everything—the little details that no one really gives a shit about—separate. But of course, as the creative, those [details] are life or death.

And I can’t make noise and techno under my government name. It was time to unleash the Quiet Husband. I’ve been sat on the name for ages and it fit perfectly for this. But I’m not going to do any more aliases. I think this is it.

So what does the name mean?

Quiet Husband is based on my best friend’s stepdad when I was maybe eight or nine. It was the way he would look at you—I’d catch glances and it’d freak me out. And, of course, it bleeds into all kinds of people. It’s that figure you don’t fully trust.

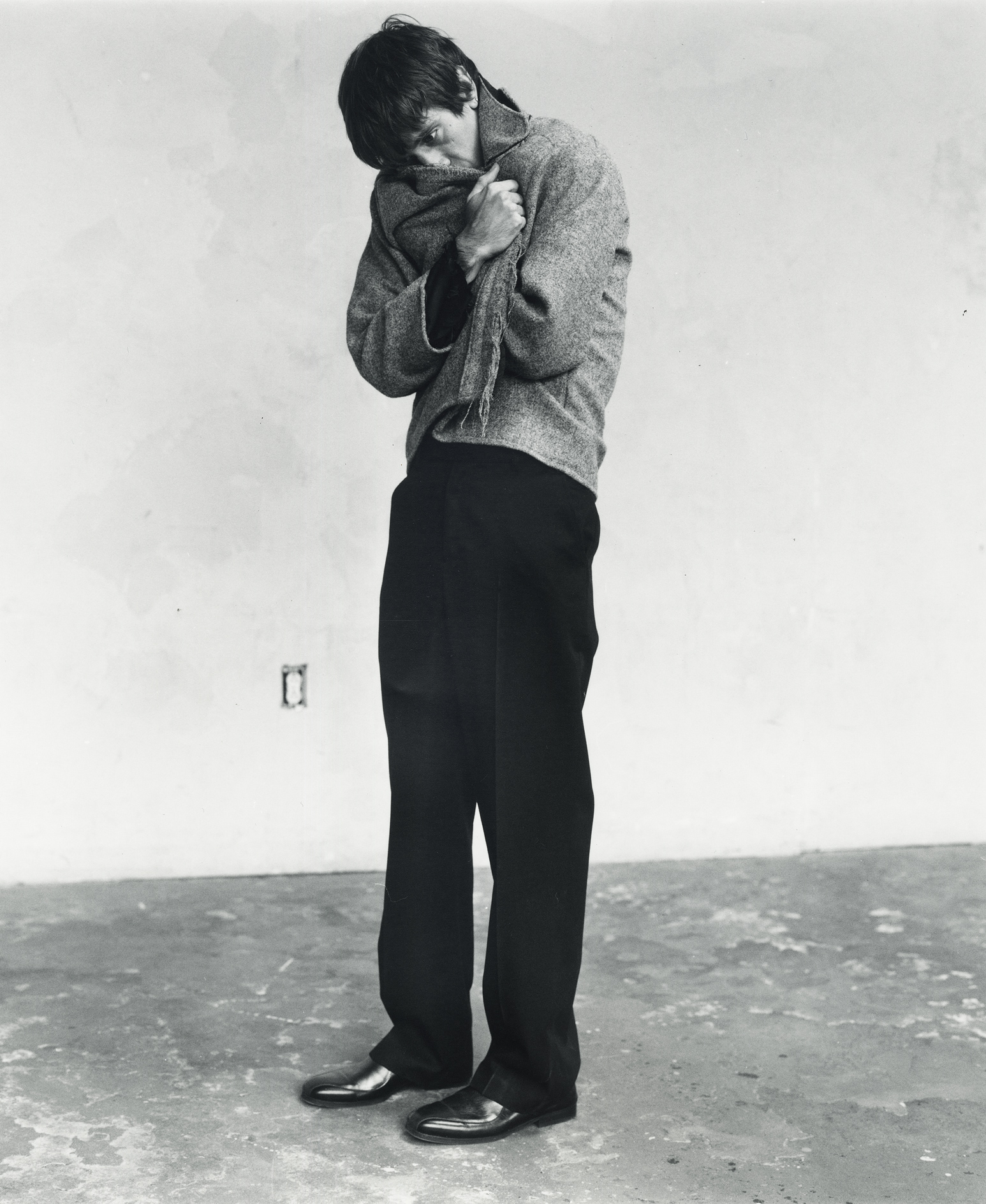

That feels connected to the text that accompanies the record—which references a lost man and loneliness and melancholy. It all points to the fraught nature of masculinity now, what it’s “supposed to” be. I imagine, especially as a father, that’s something you are grappling with a lot.

I swim in those worlds constantly in recovery, and being a dad to two boys and a girl. I’ll just speak about the boys in this particular sense. There’s a lot of pressure to raise them into the world. It’s a really fine line to walk. There are things that I relate to in them and that I’m trying to harness and push and not push too much and rein back in. There’s a whole PhD topic within the name Quiet Husband, probably.

Do art and academia go hand in hand for you?

I’m in my 40s now. As an artist, I’m continuously trying to educate myself and push my work in different directions. I’m making a trap record next, for instance, pushing the spoken word into a lyrical flow kind of thing. But I’m at a stage now where I need to be teaching as well—not necessarily in a school or anything like that, but I’m aware of people looking at me. I’ve been using social media as a way of that recently, dropping little insecurities and struggles—struggles that every artist has, but not everybody wants to talk about publicly.

It feels like every exhibition is going to be my last, every record is going to be my last. So I’m not thinking, How am I going to continue to do this? There’s so much insecurity in this lifestyle that we choose as artists and creatives and writers and anything under the umbrella of art.

How do you let something go with that feeling that it might be the last thing that you put into the world? I’d imagine that feeling would have the opposite effect on most.

I realize that I am prolific and that a lot of the things that I do could just stand as one thing in a year. But it’s just my process. I don’t know what I’m working towards. I don’t know if this is all going to culminate into something—if the best is gone, if I’m declining.

I’m [working in] the music world and the visual world, and one overtakes the other sometimes. Music seems to be leading the way at the moment. But I’ve always seen the art world as five steps behind the music and sound world, so it feels normal that that would be the case. The Quiet Husband alias has managed to make the gap further apart, as in, I’ve got space now to do more and not look like I’m a workaholic.

The concept of substitution is super prevalent on the record. Listening to the album almost had that same effect: When it finishes, there’s this sort of void that you are left wanting to fill.

I was aiming to bridge noise in techno and make it one genre. The techno on the record is pretty industrial and almost undanceable, and the other parts are like segues, but quite intense ones. The text for the record, by Charles [Teyssou] and Pierre [-Alexandre Mateos]—two French curators—is an important part of it. It also kind of sits completely random within it all. I think, having just finished at the Royal College of Art and [being] in the art world, everything needs to have a concept and a “what it means,” and the “why did you do that?” I fall into that trap. It needs to be there, I guess. Even when my kids are drawing a picture, I ask, “Why did you choose the color red?”

But for this, I just wanted to make a record that has no meaning. It’s a record about nothing, that challenges how you listen to it, why you are listening to it. The titles are all extremely important, of course, the blocking and substitute element, and a concept comes—quite a heavy one—but as I was making it, I felt relatively free and almost like I was on the brink of a new genre, which, incidentally, Mary Anne Hobbs called void core. We wanted it to be an unfriendly record. Not in a pretentious sense, but I don’t want it to go around the parameters of what is acceptable for a dance floor. I can’t imagine anyone putting it in their set.

Maybe it’s more approachable because there’s no “right way” to go about it.

I think that’s always my goal, even with the spoken word stuff. What I love about the noise world is there’s kind of nowhere to go from there. As much as I love music and all its genres, as soon as you start hitting the noise territory, you’re kind of at the summit. I’ve been obsessed with how can I educate myself into listening to noise and accepting it as a texture and not necessarily a melody or anything that has any rhythmic value. I don’t think there’s a musical expression that is more academic than noise. It’s like an abstract painting. It’s people thinking not even outside the box, they’re thinking outside the planet.

Your mom was featured on it—what does she think of it?

It just goes as far as, “Are you still doing the music stuff?” or “Are you still doing the art stuff?” I say yes, and that’s good enough. She’s approaching her 80s now so we don’t go into much about it. She’s the sort of woman who would give you a birthday card and cry herself because of the writing on the front of it—because of why she chose it on your 35th birthday, because of the man you’ve become. So I think, I just said to her, “What’s the most important thing to you?” and then pressed record. And she was like, “Family, being healthy is the main thing in your life.” And then I just took it on loop, and pitched it down. I’ve kind of stuck with it in the same way that noise is just kind of like one tone or just absolute hecticness.

Where did you look for inspiration in making it?

Because I’m a painter, I see the parallels hugely between conceptual, minimalist painting and noise. Even just in the band names—Climax Denial, Cheapest Coffin, Straight Panic—it’s always really intrigued me. You know when something just touches your own creative pulse or makes something inside you smile? I’ve always seen it very much like painting when I’m in the studio, in a flow with the music. There’s nothing better than being lost in gestures. When you’re making noise, you’re questioning your own sanity while you’re doing it—doing something that no one’s gonna want to listen to or be able to sit through. And that links to horror films and as a kid watching Freddy Krueger or Jason Voorhees or Michael Myers. Like, Why do I want to keep watching this? I’m not going to want to go to bed. But still, I was just obsessed with seeing it through. It’s the same with the noise thing. I’m questioning why I’m doing this, and there isn’t an answer. I love that.

Music is maybe the only thing where I would feel any hesitancy telling an artist that their work made me uncomfortable. Your’s did and it’s intentionally unsettling, but it still feels awkward to say it—even though it wouldn’t with a painter or a filmmaker.

If I sit and listen to a Climax Denial record, it brings up emotions and parts of my inner dialogues that I wouldn’t have ever imagined being able to go—really positive places and really challenging places. I’m listening to the roar of white noise or screeching or metal clanking, and it’s visual. I owe so much to the noise world in my overall output. It’s almost like a secret that I don’t want to give people. It’s like, Trust me, go and listen to this record. Just sit down in a dark room with your headphones on and listen to it. You transcend.

And don’t get me wrong—I love as much as the next person to put Radio 1 on and listen to Central Cee and Adele. I definitely have space for that. I’m not a purist in any way. Actually, I’ve come to terms with the fact that I’ve never been a purist in anything. One of the main things I’ve learned through my creative journey is to watch other people, especially young artists, and embrace that. If you don’t understand it, try to understand it. I love not understanding things. Like going into a museum and instantly dismissing stuff because it’s figurative, or because it’s too colorful and, all of a sudden, you realize what seems a basic painting of a sunset was done by some outsider artist.

That’s interesting because, at the beginning of our conversation, you said you wanted people to experience the record without context.

That was a big conversation at the well, for me at the Royal College: Can a painting just be a painting? Without it, it just becomes about the artist’s skill or lack of skill. I guess you do need more information.