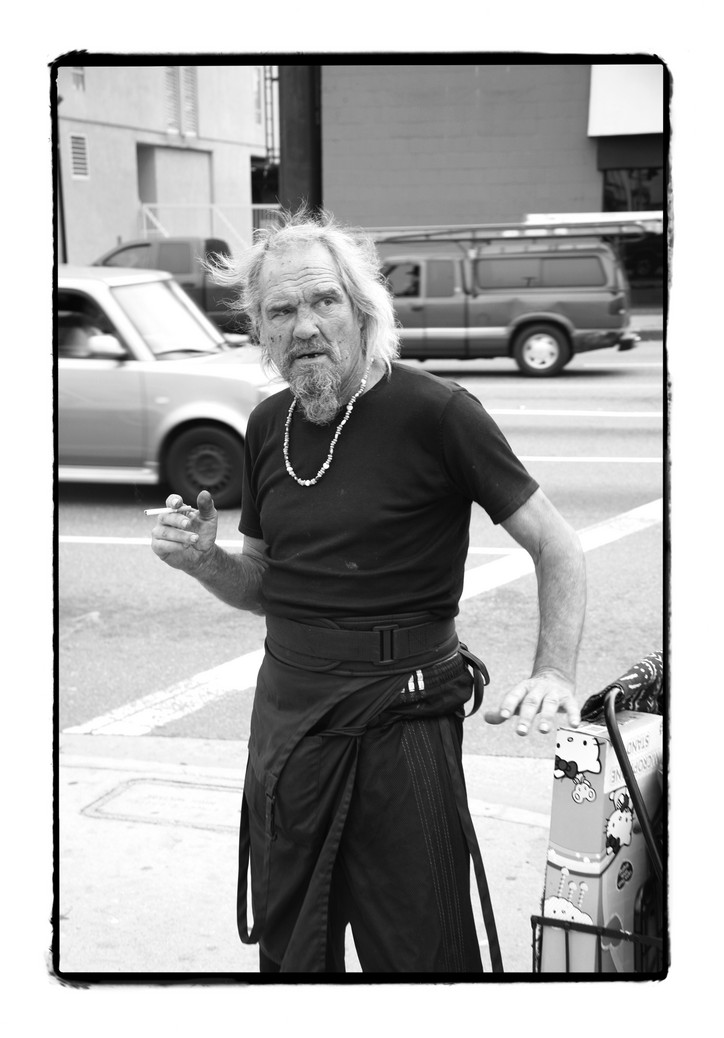

Wages of Sin

Remy Lagrange’s photo series, “Wages of Sin,” is on view at Milk Gallery as apart of adidas Showcase X through July 29.

Stay informed on our latest news!

Remy Lagrange’s photo series, “Wages of Sin,” is on view at Milk Gallery as apart of adidas Showcase X through July 29.

“My first show with James, I’d just graduated college and I was really interested in academia and theory,” yi Hou told me over Zoom. He was preparing to unveil The beat of life, and I was at my boyfriend’s mother’s home in Yuma, on a month-long road trip interviewing strangers before the election. It’s been a whirlwind much like yi Hou’s experience of 2021 and 2022, cranking out art.

“[Academia and theory] heavily informed my practice,” yi Hou told me. “They still do now. But, this was prior to having lived life as an independent adult. As the years passed since graduation, a lot of the theory that I was reading started to be less applicable and less relevant.” Days later, my colleague Dorian Batycka posted an IG story of a classical sculpture from Art Basel Paris with a similar idea: “The fact that no one can (or wants to) make this anymore points to a wider problem: that art has become so obsessed with concept/theory (and money) over basic form.”

Thus, yi Hou is now drawing from daily existence — from “nightlife and putting myself out there,” he said. “Having sex — at least for gay men or queer men, that is a great way to make friends.” The title of his new show once again draws from a poem he wrote. It evokes police violence and music alike by referencing the thrum of a heart in a chest.

Birds of a Feather aka: Chinatown Gangsters, 2024.

The show itself simulates that sensation. For the first time, yi Hou presents several scales across The beat of life, which oscillates like a pulse between small, close-cropped busts of compatriots like yi Hou’s boyfriend, and larger arrangements like Birds of a Feather aka: Chinatown Gangsters (2024), which depicts yi Hou alongside artists Amanda Ba and Sasha Gordon. (Perhaps he’s angling for a Deitch show, too.) Across sizes, yi Hou amalgamates oils with gouache, graphite, and more. Yet, these works bear new marks of maturity, like the honesty of discerning one’s strengths and the power of saying less, a confident refusal to explain further.

Orange and magenta still flash throughout yi Hou’s linework, but rather than sculpting figures from many maximalist flat blocks of color, yi Hou has spent time tenderly rendering flesh and fabric true to life. Supple cheeks exposed via rich assless chaps greet guests entering The beat of life from Coolieisms, aka: Born in the USA (Go and Kill the Yellow Man) (2023-24) — a painting named after Bruce Springsteen’s famous hit. Obama used the song to counter birther conspiracies, while Trump plays the pithy American critique patriotically at his rallies.

Coolieisms, aka: Born in the USA (Go and Kill the Yellow Man), 2023-2024.

This initial artwork hails from yi Hou’s ongoing Coolieisms series, which reclaims a 19th-century slur for exploited Chinese rail laborers by depicting Asian figures in the trappings of Americana.

“Was there a leather daddy back in the 1800s working in the mines?” yi Hou mused. “Probably not.” In Coolieisms, though, he uses his own visage and imagined characters to forge fictions that highlight stereotypes about Asianness, masculinity, heteronormative culture, and more.

Yi Hou has previously spoken about the paradox of representation, that newfound art world fixation. Representation isn’t necessarily action, but it’s necessary for an equitable society. “It can be a burden to think about these things, but it's also quite generative,” yi Hou added. Symbols carry historical meanings, while also offering canvases for each viewer’s projections. They’re ephemeral, but spark material impacts. There’s a chilling reality, after all, to rooms full of people singing “Go and kill the yellow man,” regardless of which politician might be playing it.

The Coolieisms series was once the one place yi Hou exercised license. “I was interested in the ethics of portraiture and trying to not commit any symbolic violence to another person through a painting,” he recalled. “As I got older, I was like, ‘wait, none of my sitters give a shit about that.’”

Symbols offered a sort of camouflage that enhanced while encrypting meaning. They’re active here, too. Yi Hou’s use of the color wheel proves somewhat new, but he’s harnessed sheriff’s stars and yin-yang signs before. “I've been interested in opacity and obscurity, generating mystery or opacity through these symbols,” he said of his compositions. “Because I've talked so much about them, they're a bit transparent now.” In another interview, yi Hou noted that sometimes indirect communications convey more. Thus, he’s set such icons ablaze in works like Self-portrait (25), aka: The beat of life (2024), “to further obfuscate the meaning behind them.”

Sailor Moon Rising aka: Pacific Passenger, 2023.

Even the show’s environmental elements carry palimpsest connotations. Cranes soar throughout that same self-portrait — in China, they symbolize longevity and luck, but these birds feature prominently, too, in the murals across Alamosa, CO, where the birds pause for a month or so each fall during their annual migration. Maybe the Navy man seated beside the sunflowers in Sailor Moon Rising aka: Pacific Passenger (2023) just likes those flowers, or perhaps he’s optimistic, as they’d allude. Or, maybe he’s from Kansas, where they adorn state highway signs.

Yi Hou’s affinity for the Beat poets first attracted him to America. He has yet to travel the country himself, though. Maybe he’s better off. We’ve met many people out here who espouse their open-mindedness without demonstrating it. One man in Iowa told me about his gay friends, but called protestors “thugs.” Americans appear inept at estimating themselves, but art actually does expand horizons. Another man in Idaho said that while discussing “On The Road” with a friend, he was shocked to learn there’s gay sex involved. “I’ll be damned,” he said upon a return read.

Exposure is the answer to the biases still dogging America. Maybe representation isn’t the final solution, but it’s a good start — one that yi Hou is evidently mastering. “I can actually refuse any kind of closed meaning or thesis in whatever I make,” he said. “That's what I was doing with this body of work — the work inherently has a kind of politics and thinking behind it, but I feel it was less didactic and a lot more free.” Seeing alone has its power. The beat of life is an exercise in it.

The beat of life is on view at James Fuentes until November 16, 2024.

Accompanying the new installation a floor above, Ad Reinhardt: Print—Painting—Maquette similarly contemplates light and color through more traditional media. The show celebrates a series of prints, Ten Screenprints by Ad Reinhardt, the artist made in response to his traditional paintings. It is smartly curated, a sharp presentation of a complex body of work. A work on paper “ur-proof” is framed aside its accompanying finished print — the idea and its execution. In this way, we can see how Reinhardt worked to transmute his oil paintings to the hyper-flat surface of a screenprint. It feels like it was curated by an art teacher, eager to show the process as its own form. It is a nice show and seems in line with the numerous works-on-paper gallery shows and fair presentations of other contemporary masters this fall (I want to ask the aforementioned Christie’s exec: “In our current macroeconomic environment, are works on paper inferior goods, macroeconomically speaking? Like, because of the vibecession?”).

And then downstairs, Doug Wheeler. For the buzz? But there are no phones allowed; you won’t see it on TikTok. Even the gallery’s glossy photography seems to keep the piece, DN ND WD 180 EN - NY 24, 2024, at a distance, presenting it as an almost lifeless backstage. I snuck in just before the gallery closed for the evening. The line was still long — "how many people thought they were waiting for free alcohol?”, I wondered. You are allowed to view the work in shifts, and gallery docents usher small groups of people through at specific intervals.

As you wait to enter, you sit on a bench beside a rubbish bin of crumpled protective booties, similar to ones you might wear touring an apartment on Billionaire’s Row. From your seat, you can see into a glowing room, subtly fluctuating in luminosity and laced with occasional cool purple tones. The installation has only one passageway, so you see the faces of the previous group as you enter: almost certainly awestruck and delighted.

My viewing companions were an affectionate couple and a solo woman. We entered a cavernous room featuring two sheets of light — the platonic ideal of a white cube. I initially thought the booties were props in commodity theater, but immediately, was impressed by a quiet space free of any marking; its hermetic qualities are essential to how DN ND WD 180 EN - NY 24, 2024 works. In front of the glowing portals — almost oversized depression lamps — are two quadrilateral inlays made of glossy epoxy rather than the painted matte white of the rest of the room. They feel like shadows to the light walls, and I was careful to transgress them initially, not knowing what was precious and what was participatory in the space. I gingerly slid onto them, approaching the walls of pure light. The best comparison I can make is to the windows of the aliens’ ship in Arrival. Having this reference in mind, and summoning my best Amy Adams, I looked through the portals to a misty and otherworldly space of unknown dimension. It was clear to me what was going on: ahead was a sheet of glass, mysteriously recessed behind some kind of beveled frame and beyond a misty room with some sort of light installation hidden among fog machines. It was nice, I thought, a subtle perceptual trick, a refreshing moment of quiet in Chelsea’s maelstrom of glass and speculation.

Imagining glass, and the ensuing tragedy of a migratory bird flying to its brisk end on the glass of a Billionaires’ Row skyscraper, I was careful in my approach. I inched my head closer and closer to the light wall, and finding nothing, looked to the docent for a suggestion on how to proceed. He smirked and motioned me forward. I took a step and entered a white void.

I started laughing. The woman started laughing. Beyond the light walls is a “ganzfeld”, a featureless room within which light itself feels thick, voluminous, and softer than it does elsewhere. I walked forward into seemingly endless space knowing logically, though somewhat disbelieving, that I would soon hit something. Eventually, my feet caught the slope of the floor, seamlessly curving up to join an invisible wall. My first experience of DN ND WD 180 EN - NY 24, 2024 can be best described as near-constant discovery. The work does not yield itself to quick-glance judgments, what you think is happening is often incorrect. The initial room of the installation, what I later understood as an antechamber, is pleasant, but underwhelming. It was not the heaven I was promised. However, each subsequent exploration — stepping onto the epoxy, moving through the portals, and walking around the ganzfeld — felt daring and unexpected.

I could describe the work poetically: behind all seen things lies something vast; the process of knowing is a path that can only be walked in one direction. I could find a metaphor. Plato’s cave is the most salient. Or maybe gender: the passageways as a fictively dualistic representation of gender norms, the ganzfeld the truth of our unbounded humanity. Or perhaps psychoanalysis: the vestibule, the superego; the passageways, ego; and ganzfeld, id –– arrange this set differently, my Freud is rusty. Or, narratively and spiritually: the vestibule is a pleasant purgatory of sorts (maybe life itself), the passageways faith and disbelief (or death, two ways), and the ganzfeld a serene plain representing the most optimistic notion of the persistence of our souls. But Wheeler and Zwirner offer us no such poetry, only the concrete referent of DN ND WD 180 EN - NY 24, 2024 a plane flying through night and day’s transition wherein to change direction is to gaze upon a different temporality entirely.

To this end, a purple light begins on one side of the field and slowly dissipates before swelling subtly on the other side of the space. The light seems to decrease in luminosity at some points, feeling materially heavier or lighter depending on where you are in the work. I had walked to the edge of the work, in line with the passageways, when I began to see a subtle pool of shadow, defining an area of the floor. I walked through it, tracing out the outer edge of the installation. For another passage, I focused on the sounds I was hearing while moving through the work. As I walked, I spoke to myself, enjoying the incomparable echo of that space. At once, I felt a pressure in one ear and noticed that I could only hear the echo coming from that side. I realized that I had, through sound alone, found the precise centerline of the installation. In these ways, the work can really only be made sense of through experience and exploration. Wheeler’s installation seems to spatialize intuition itself, wherein the viewer is forced to trust embodied knowledge in an encounter with art, a very rare moment.

Doug Wheeler, DN ND WD 180 EN – NY 24, 2024 © Doug Wheeler. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner.

Doug Wheeler is a first-generation Light and Space movement artist (think Robert Irwin, Larry Bell, and James Turrell) and a lifelong pilot. He has described flying as total immersion in light, a disorienting situation in which directions can become confused. For this work, a mature ganzfeld study from the 84-year-old artist, Wheeler has condensed his considerations to the precipice of a day as observed from the air. Having never flown, my understanding of this phenomenon is largely informed by the writing of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, who described the deserts of his crashes as similar to flying through a void. Wheeler’s installation is the closest I have come to feeling the sensations he described. Wheeler articulated his early hopes for his work in a 1968 interview with Time magazine, saying, "I want the spectator to stand in the middle of the room and look at the painting and feel that if you walked into it, you'd be in another world." Only 56 years later, he has given us that other world.

Photographs of his work are almost crass. Visitors look as if on a Hollywood special effects stage, dwarfed by flat nothingness. A camera cannot capture the strangeness of being in a space without knowing its volume or the completely enveloping field of light that is the ganzfeld. But they do show something essential about his installations, a body suspended in light. Though it makes a boring photograph, when you are that body, all you can perceive is that light, as thick as space itself.

The work is so elemental, so stark, that it is difficult to describe using precise language; it is difficult to speak about it objectively for this reason too. It is most comparable to an architecturally scaled sensory deprivation tank, and I found myself wondering, on a very literal level, where the work ended and my imagination began. Most visitors leave swearing there is a fog machine hidden somewhere. Wheeler’s work draws a fine line between desolation and hallucination, literalizing and materializing light itself. Within DN ND WD 180 EN - NY 24, 2024 I found myself thinking about the vacuum of space. It is difficult to imagine a void because light and matter are ubiquitous in our experience of existence — we often experience air and darkness as emptiness, though true emptiness is not something we have ever encountered. Space itself feels thick inside Wheeler’s installation, and the work allowed me to feel the presence of my existence as a being made of matter within a constant soup of other matter. There, surrounded by more things than in most moments of my life, I was able to imagine nothing.

Since experiencing it, I have craved it almost hourly. There is a house I visit in my dreams every other night or so. In it, there is a hidden room only accessible via a secret pathway. In months past, I have not been able to find the room, and, when I have, other people have been there. Recently, Wheeler’s ganzfeld has taken its place. I will leave a space and suddenly will have entered its void.