Wear Me Down: Martine Rose

Despite this being my first time meeting the designer, her studio feels familiar. Not only is Crouch Hill where I grew up, but I have been an avid customer of Rose’s for over five years—so much so that my ex-boyfriend and I would send her pictures of ourselves wearing the clothes.

“Oh my god, yes!” she says when I remind her. “It made me so happy, thank you so much. And that was when really no one knew who I was, as well, so double thank you.”

Indeed, it is only in the last few seasons that Martine Rose has really come into itself as a brand, extending its reputation well beyond the streets of London. Rose’s success is no doubt related to her newfound association with Balenciaga and the ultra-hip Vetements clique responsible for the label’s new direction, but it has as much to do with her relentless devotion to a core personal aesthetic.

“I did what I was doing for a long time and it just came full circle; it’s just that a lot of designers don’t stick to it for long enough. That’s not a criticism, I could have given up, and was very tempted to give up lots of times, but I just didn’t know what else I would do.”

Community-minded yet fiercely independent, tomboyish in many ways, and a proud product of the “Windrush” generation of Jamaican immigrants welcomed into the UK throughout the ‘50s and ‘60s, Martine Rose personifies London’s most positive characteristics. There is a sense she could only thrive at this level in London, a city where Fashion Week has a unique reputation for supporting emerging talent in a way that craft-focused Paris or commerce-hungry New York simply does not. A lot of that is the result of Lulu Kennedy’s support of small brands through her non-profit project Fashion East, support which Martine is still incredibly grateful to have received. But despite her ascendance, London’s greatest recent success story is, in her own words, a ‘notorious loser.’

“I was up for LVMH—didn’t win. I was up for ANDAM—didn’t win. I was up for the British Fashion Awards—didn’t win. I quite like that. It’s reassuring because it means people still aren’t quite getting it.”

Perhaps because Martine had never imagined herself as a fashion designer, she is able to maintain a distance from her industry. As a child, her interest in clothes came from music and club culture rather than the runways of high fashion.

“I wasn’t one of these kids making clothes for my dolls and shit like that, you know? I was always interested in clothes, but not really fashion. I was interested in what people wore, and why they wore it, and where they wore it. That’s more of a club culture thing. It’s quite Jamaican, too. There’s a certain style and approach to fashion in the Jamaican community, especially my dad’s generation, and the subsequent generations here in England. There was a particular style and swagger that I enjoyed. But it wasn’t fashion.”

Drawing a distinction between style and fashion is crucial in understanding Martine’s approach, one rooted more in a passion for individual flair than for the highbrow concerns of an elite industry.

“When I go to an actual atelier, I’m definitely an anomaly. There’s not many people like me. And when I say not many people like me I don’t just mean not white—but that also—I mean normal. When I go in we’re both a bit in awe of each other.” Luxury versus streetwear is another dichotomy that designers and critics alike seem utterly fascinated with, but though she enjoys a crucial role at Balenciaga, so-called high fashion is not something that Rose ever coveted. “I didn’t give a shit about Gucci. It had nothing to do with me. My sister was really into Gaultier, the stuff that had a currency on the street as well. It went from the street upward.”

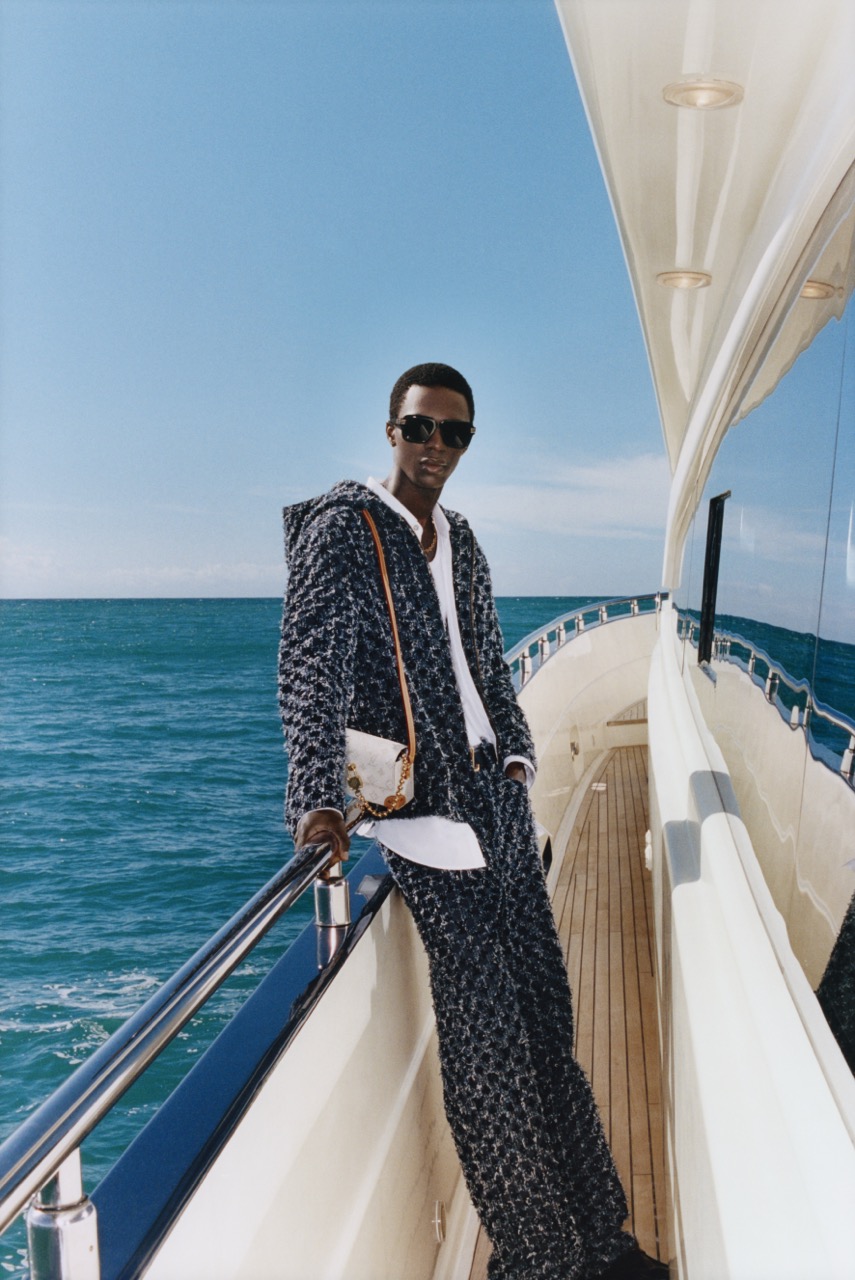

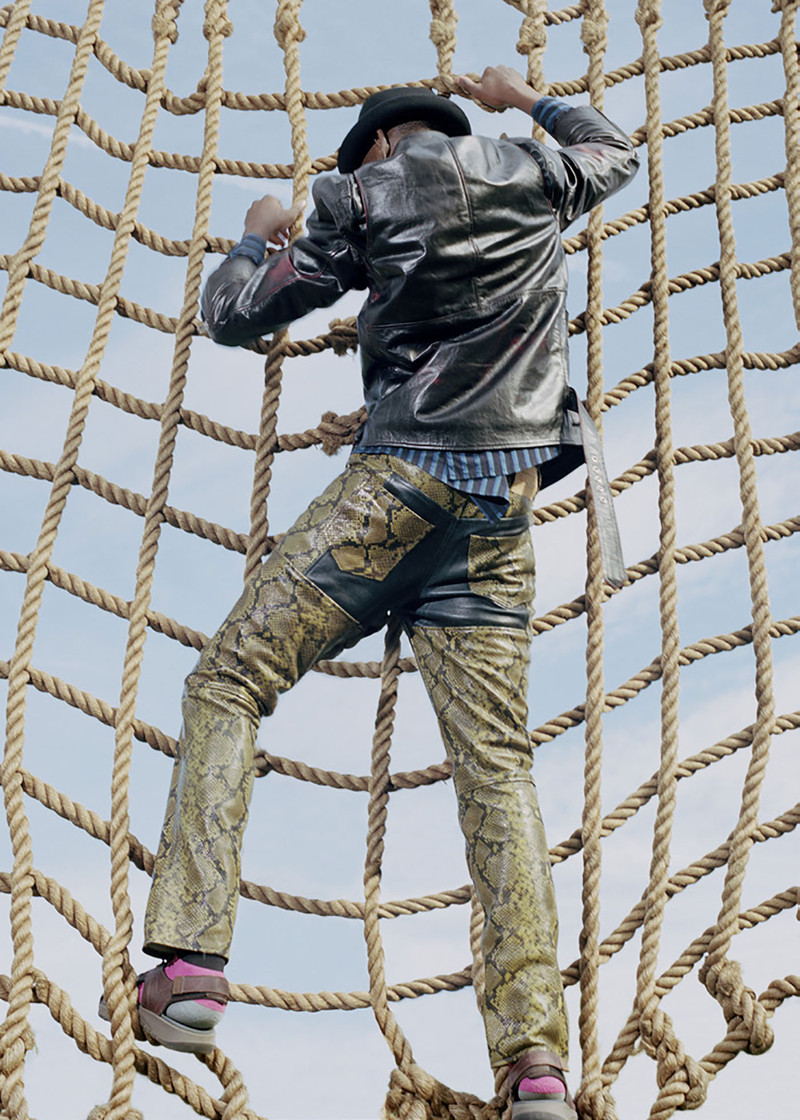

Martine’s lack of real concern for the industry elite is no pose. While she manages to forget the names of heavyweights like Ralph Lauren and Tim Blanks, Rose is at her most precise when discussing subcultural fashion heroes like the Lo Lifes and Dapper Dan, part of a wave of creatives in low income neighborhoods who took luxury and turned it on its head. If the American dream was being withheld from Black youth, New York’s Lo Life crew were damn sure going to claim it anyway, boosting the ultimate symbol of Americana, Ralph Lauren, from Macy’s starting in the late ‘80s, and sporting it with the rebellious streetwise spirit that has since come to buoy the brand’s relevance.

Around the same time, Gucci and Louis Vuitton were refusing to sell to Dapper Dan’s Harlem boutique because he was Black, so he bought off-cuts and garment bags emblazoned with the houses’ monograms in order to create his own flamboyant designs. Last season, Gucci copied one of his most iconic designs without due credit, then in a quick volte-face hired him as a consultant and collaborator on a Dapper Dan collection of garments. The genius PR move managed to quell dissent around Gucci’s racist past as well as its unauthorised use of Dapper Dan’s designs, but unfortunately reinforced the notion that luxury saves streetwear, and not the other way around. Rose is well aware of which is the more inspirational.

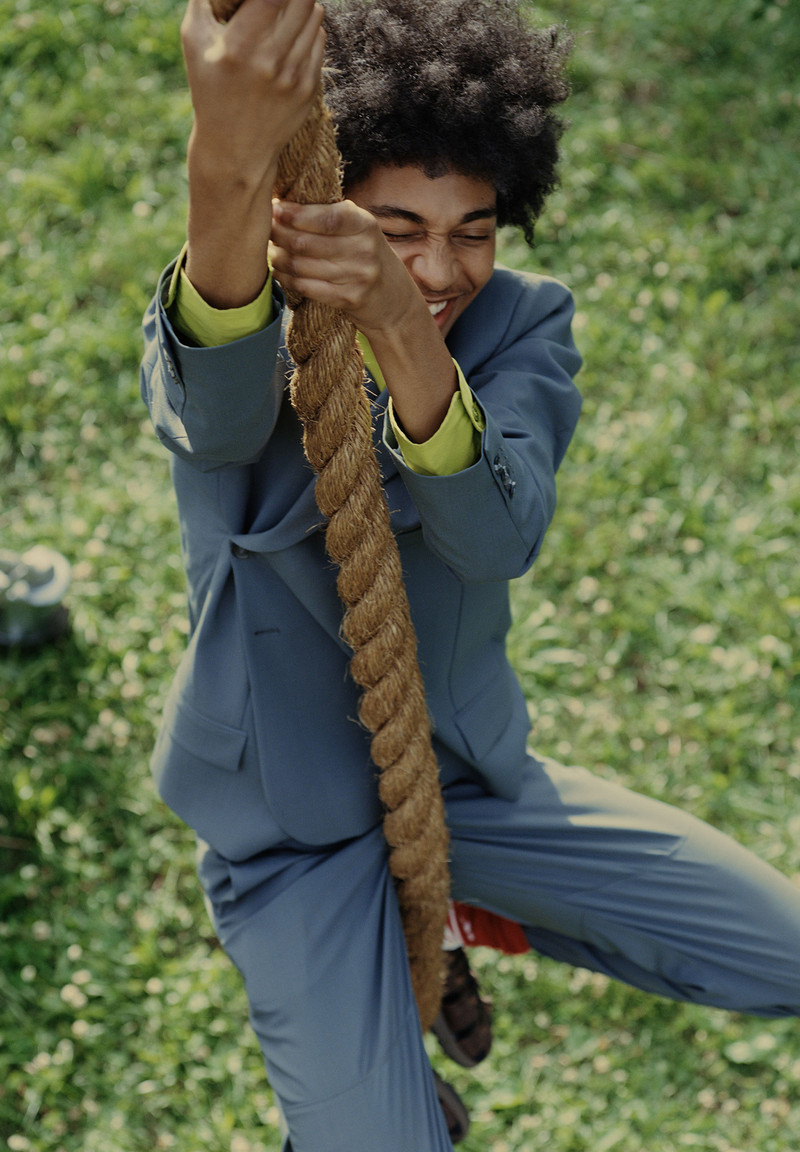

Regarding Rose’s work with these underground histories in mind, the influence is clear, whether in the luxury urban outerwear aesthetic of her immensely popular Napapijri collection, or in her unabashed logo appropriation, a practice that has gained her significant notoriety. In Martine’s hands, such brash co-option has a cheeky agitational effect on a conservative industry. Carlsberg, a Danish beer brand popular among soccer fans, advertised itself as “probably the best lager in the world.” Now, according to her Instagram bio, Martine Rose is “the best fashion designer in the world.” Probably, of course.

“Do you think people take that seriously?” she asks her assistant Shaunie, who controls the social media account where the slogan proudly sits.

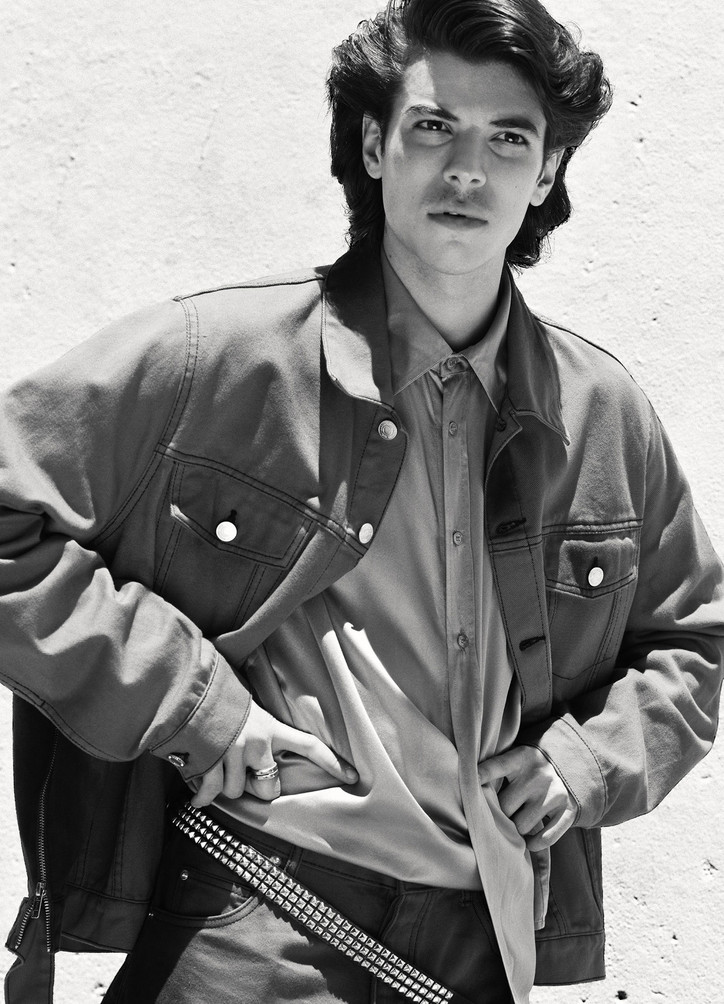

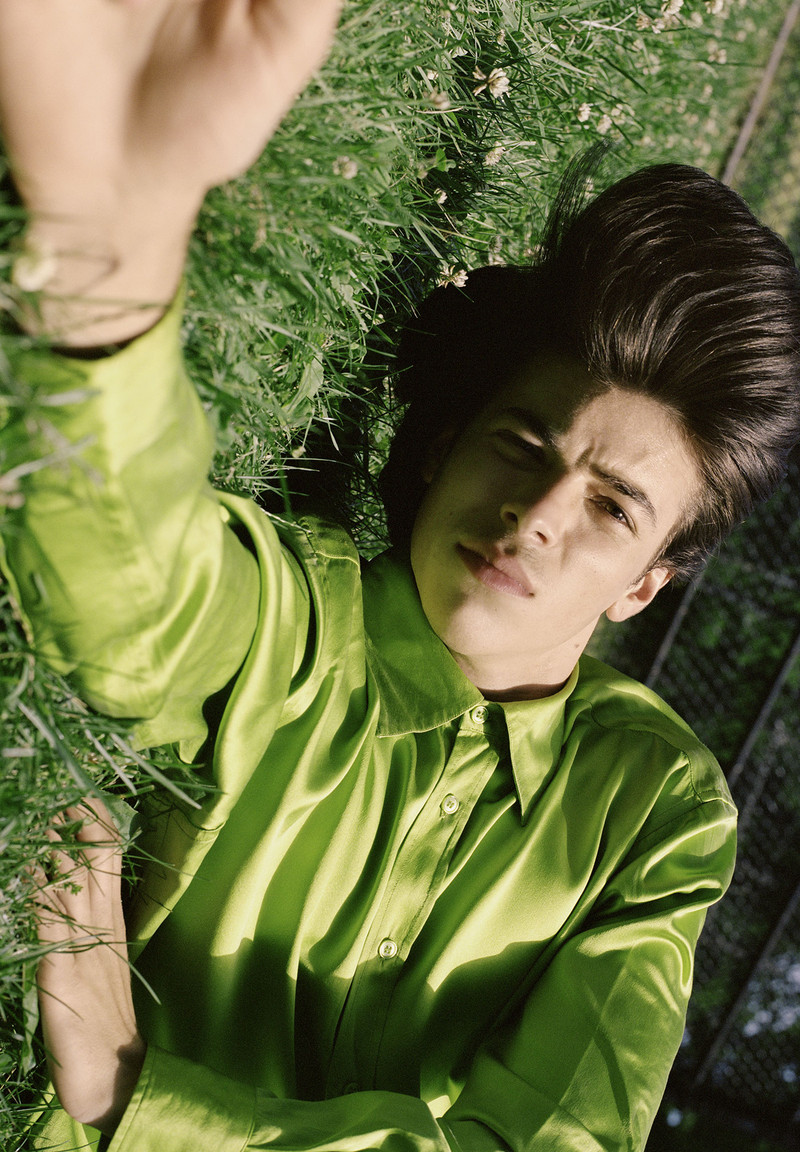

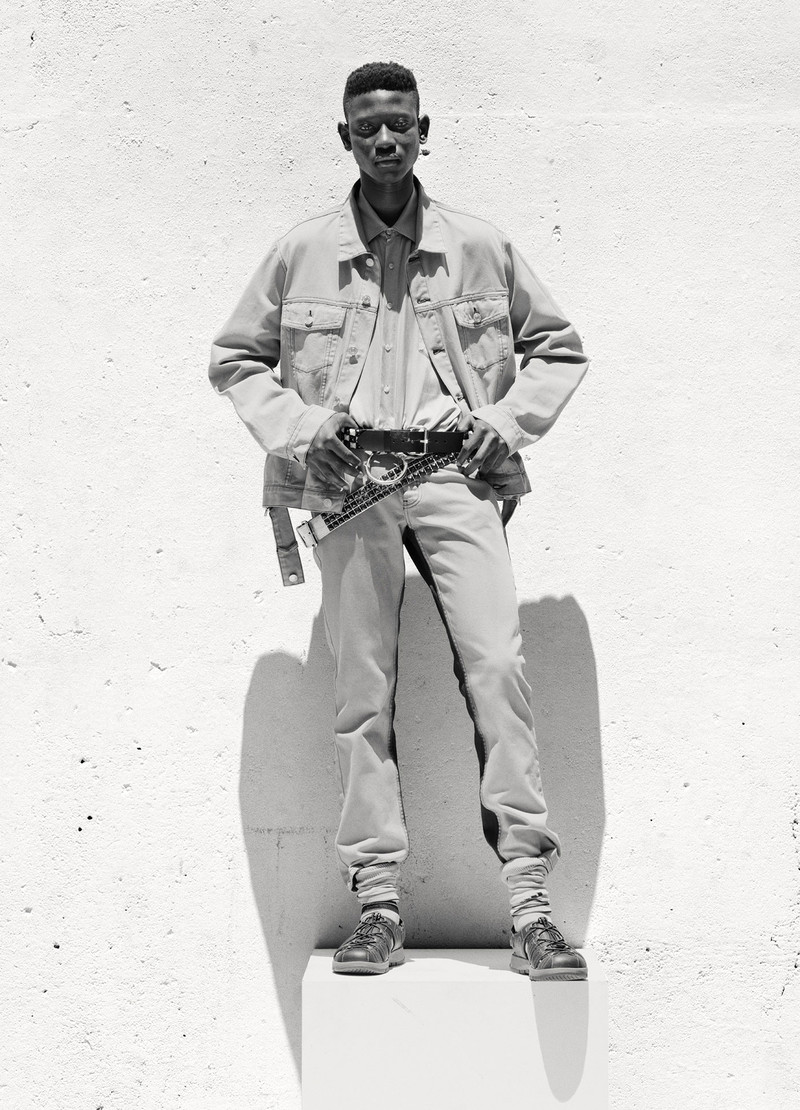

Whatever the answer, Rose revels in the misdirection. Another of the designer’s signatures is her occasionally garish take on traditional masculine dress. Together we reminisce about SS14 in particular, a collection that seamlessly brought together leather, lace, athletic-wear and wigs to be displayed on rotating platforms—a presentation technique that would also become a hallmark. A favorite was the reversible MA-1 bomber, unassuming from the outside, but lined top-tobottom in white lace. Something about that concealed extravagance perfectly embodies the gay experience to me—I tell her how my ex and I always said we were going to get married in that lace-lined bomber. The wedding never happened, but the bomber remains just as much of a stunning, meaningful piece of over-the-top menswear for me as it did five years ago.

“I like playing with notions of masculinity. I like fitting a guy in a ruffle shirt, for instance, because that for me is very masculine. I like, in the studio, redefining those boundaries of what masculinity is, and what it can incorporate.” And the rotating platforms? “That shit is coming back,” she states emphatically. “Don’t know how, but that’s forever a part of my DNA. I just love how it becomes this really voyeuristic poised quiet minute. It’s so simple. There’s nothing the model can do. Nothing happens, but something’s happening.”

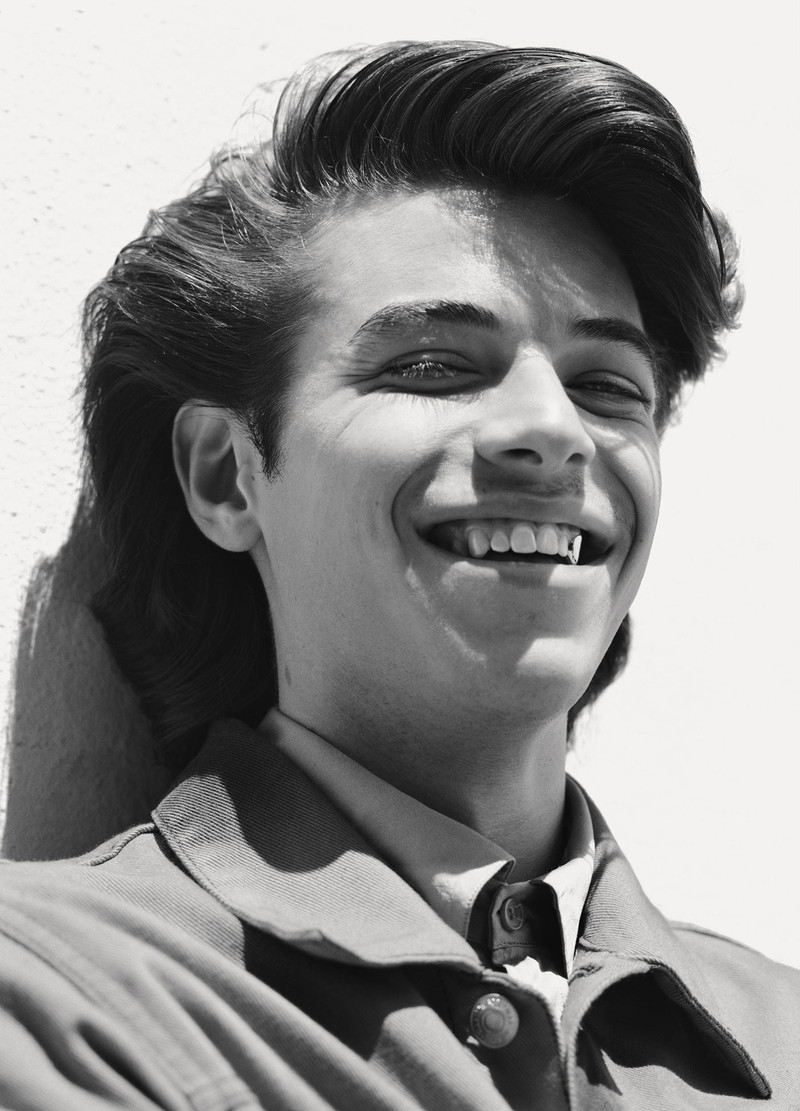

The male gaze is perhaps most typically voyeuristic, but there is a more corporeal sexual energy in Rose’s clothes. “Usually, when we’re developing ideas in the studio, we ask, ‘Would you have sex with someone wearing that?’ It makes us sound like a really lecherous group, but that’s what everyone dresses for.” With clubbing being such an important reference for Rose, it’s no wonder that a certain nostalgia for male peacocking from her teenage years informs her work. Are her collections an anthology of her dating history? “Definitely. I haven’t really thought about it in quite that context but 100% yeah. When I think about it. Yes. So now you know! You can go back and look, and be like “Who was that guy!?””

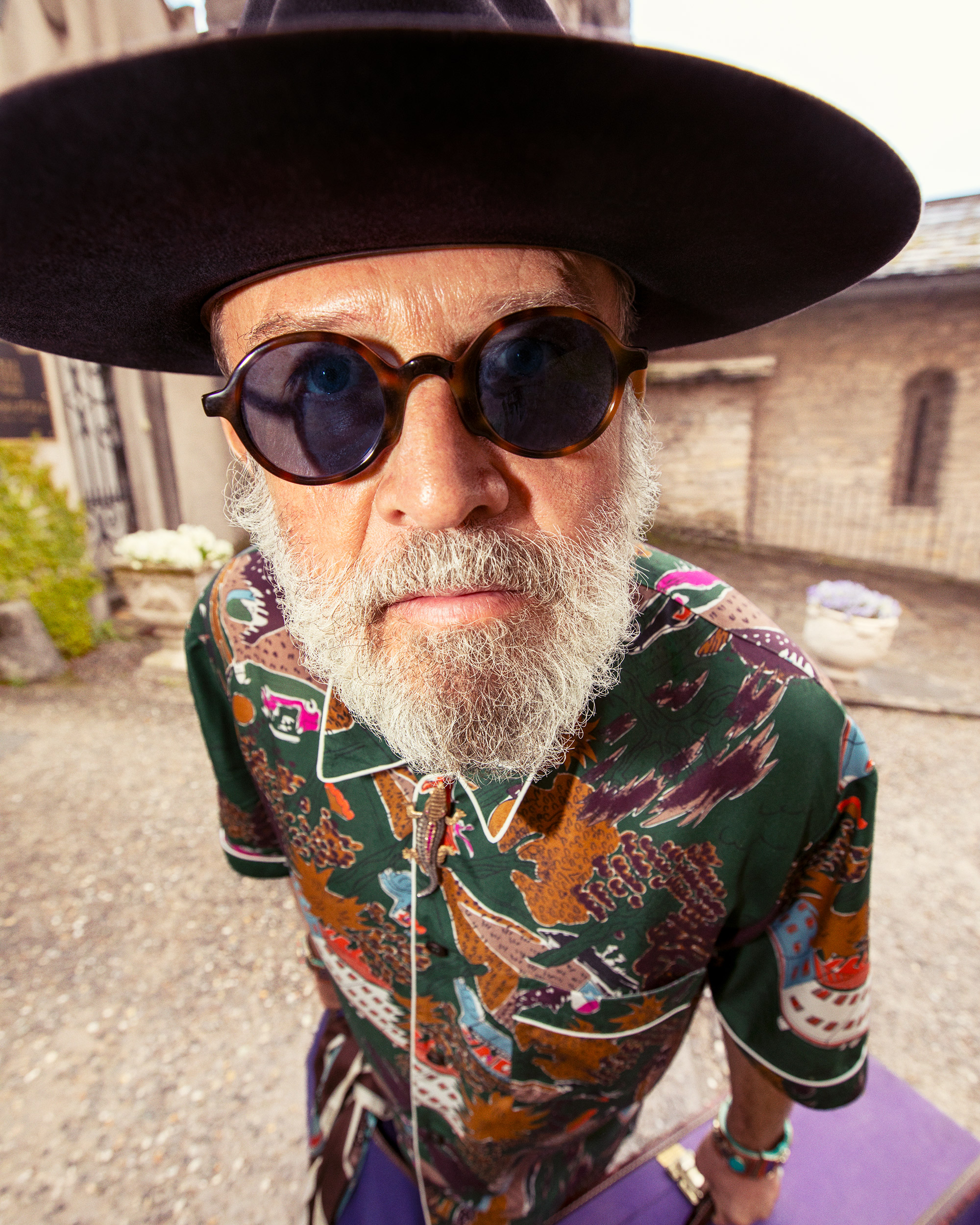

Yet the Martine Rose man is not conventionally sexy, which makes him all the more alluring. “I love awkwardness, but for me that is really sexy. It’s like when you fancy someone, you’re not quite sure why you like them, you shouldn’t really like them, but you find them sexy and that’s it. Conventional people are much less sexy for me. And conventional things are much less sexy for me.” less sexy for me. And conventional things are much less sexy for me.”

Martine’s universe always seems rooted in a very particular British male domain of beer mats and football shirts. A culture that perhaps seems at odds with the more sensitive sexual politics of the day. I propose that today genteel middle class sexual politics are being forced upon a working class culture of testosterone-fueled machismo. But Martine is not interested in speculating.

“I’m very instinctual. I don’t dwell on it or theorize it too much. Or try and steer it in a direction. It’s just quite honest. You can have all of these concepts and stuff but at the end of the day, is it attractive? Would you like it if your boyfriend walked in wearing that?”

It’s clear from how Martine met her boyfriend of fifteen years that she’s more streetwise Amazonian than shrinking violet, something that is confirmed in her gutsy approach. Construction workers get a bad rap for approaching women on the street, but that is precisely how these two linked up. Even today, Martine recalls feeling particularly elated following a recent sidewalk overture. “I was fucking thrilled because I got beeped and hooted and shouted at the other day. And I was thrilled, obviously. Absolutely fucking chuffed.” Her assistant chimes in— “Still got it!” “Yeah! Still got it! I came back into the studio pumped. And I was just like, that is so unusual, you don’t hear that shit anymore, because it became really not cool. Don’t get me wrong, sometimes it was intimidating, but never really threatening, just slightly embarrassing. But I felt a bit nostalgic. Everyone likes a wolf whistle, don’t they?”

Darren, her boyfriend, had gone the extra mile and monkeybarred down some scaffolding outside of her building to help her with some fabric. Initially brushing him off, Rose’s friend pointed out that he was “quite fit actually,” and, as the pair saw each other nearly every day while he worked on her building, they eventually hit it off. “So it was persistence. It was the monkey-swinging down the scaffold, but then it was persistence after that. He wore me down.”

Clearly, persistence is something both her and her boyfriend have in spades. Martine has presented her collections in ways that have confused audiences, the industry and fashion editors in equal measure. But she continues to innovate regardless of commercial appeal, once even showing a single look to sum up her total vision for the season. For FW13, a plan to present with three models slowly dressing themselves from a rack people are much l instead turned into a catwalk show of furiously improvised looks after the British Fashion Council accidentally assigned Rose a runway space. Did her anti-establishment approach to presentations hinder her ability to communicate to fashion industry bodies such as the BFC her needs for a given show?

“Well the BFC haven’t supported me since FW13. I haven’t been supported by them for years, so no. I don’t have any trouble communicating with them at all, because I just don’t. Last season they put me on the schedule, but in the beginning it was really difficult to do it without any support. Now, I’m really grateful. I think it’s allowed me to develop in a more natural way that suits me personally and the brand better. I’ve had to come up with more inventive ways of showing the collection and getting it out there, rather than being funneled into this system that is completely unsustainable, and becomes a real albatross around your neck.”

Her independent streak is refreshing in an industry that seems more than ever to be coalescing around a single look, and a single voice. As fashion becomes more productdriven, and advertisers hold greater power over magazines and critics, groupthink and unanimous praise is the name of the game. Those are things Martine Rose has no time for.

“I think it’s healthy to get a grounded opinion, and not this glossy celebration every fucking time you put shit down the catwalk. I mean, don’t get me wrong, if I got roasted at the end of a collection I wouldn’t be thrilled about that. It’s not like I’m dying to get a bad critique. But I’ve never been really critiqued properly. We’ve always been so under-the-radar that critics have never even thought to give us a review. We get a couple of mentions, but we never get a proper writeup. I don’t give a shit. That’s absolutely fine.”

Fashion is one of the most remarkably successful industries of the past decade, growing 5% year-on-year while other creative industries like music and film are on the decline. The cause of this rapid growth, which stands to benefit mainly the big conglomerates, has been neatly packaged, using politically progressive rhetoric, as the “democratization of fashion.” The message is greater inclusivity in a once elite industry, but the reality is a hugely expanding market for consumer goods that is largely predicated on cheap foreign labor, and the cooption of independent subcultures by large corporations. As an independent, and having witnessed the changes in London’s cultural climate first-hand, Rose sees right through it.

“It’s irritating when people try and democratize fashion. It’s really patronizing, and it’s not real. It’s bullshit. It feels like PR bullshit.” She continues, “There was definitely a shift when fashion became very product focused. It’s commerce now. It wasn’t cool to be a fashion designer when I started. It wasn’t a cool job to do. It was definitely what outsiders did, and it was not mainstream. Now, everyone’s a designer. It’s also the influence of social media. There seems to be a global trend. [Fashion] is more homogenous I would say. I think that’s just the way of the world at the moment. We’re all just really influencing each other at the moment. More than ever.”

Noticing that social media had brought out her most competitive and anxious qualities, Martine took herself off it about a year ago, preferring to stay with her finger slightly off the pulse and look at research in a new way. While this may be a blueprint for a new kind of “de-webbed” designer in the industry, there’s no doubt her customers continue to engage with her online. Still, the positive response to her latest collections, shown in real neighborhoods in London, demonstrates a sincere desire for fashion that is authentic, that exists beyond the screen.

“I think people are striving for that. Maybe we touched on it in our show and maybe it taps into something wider that people are looking for, this “real man” or this “real person,” maybe it’s this desire to connect with something honest rather than scroll through images. The “dad chic” trend—someone real and honest that doesn’t feel cool. Because everyone feels very cool at the moment. Everyone’s a fucking influencer. It’s quite exhausting.”

In both her words and her designs, Martine stands in opposition to the stifling conformity inherent in this current climate of cool. “What I find quite interesting is that it’s completely flipped on its head. Now it’s about how included you are in the gang—how many likes you get—whereas you did not want that when I was younger. You did not want to be mainstream. You wanted to keep it a secret. It was the opposite of what it’s like now. So I feel like there’s no chance for subcultures to flourish in the same way.”

The expense of London makes it a particularly brutal city in which to do new and interesting things. The community of squatters that my parents belonged to, a community that used to afford young creatives a level of freedom, is now gone. With no independent film culture to speak of, and music venues being closed at an alarming rate to make room for luxury housing and shopping centres, it seems that fashion is eating itself by devouring its most enduring references.

“Honestly it makes me cry. That on top of Windrush, and Brexit, all of these other fucking disgusting policies that are affecting London for the worse make me very sad. They show no respect for these communities, and people who have brought love here.” This is why Rose remains skeptical about the idea of “democratizing” fashion. “But there we go. What can you do about it? Moan in interviews and then contribute to the whole fucking thing!”

office issue 09 is out now. Buy it here.