Welcoming the New Year with David Zwirner

For more information on the exhibitions or to make a gallery appointment, visit David Zwirner here.

Stay informed on our latest news!

For more information on the exhibitions or to make a gallery appointment, visit David Zwirner here.

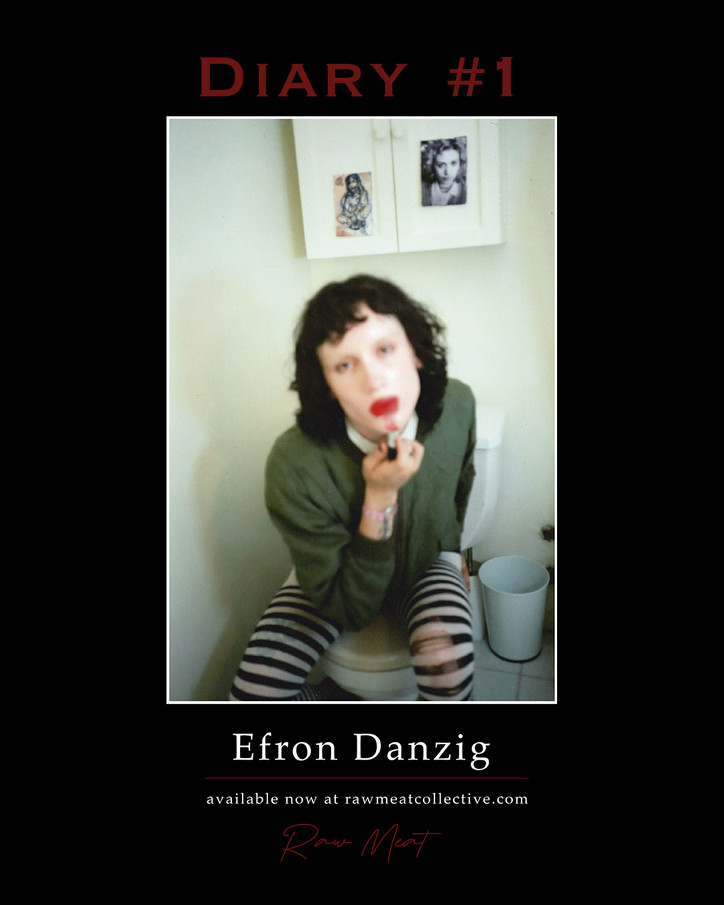

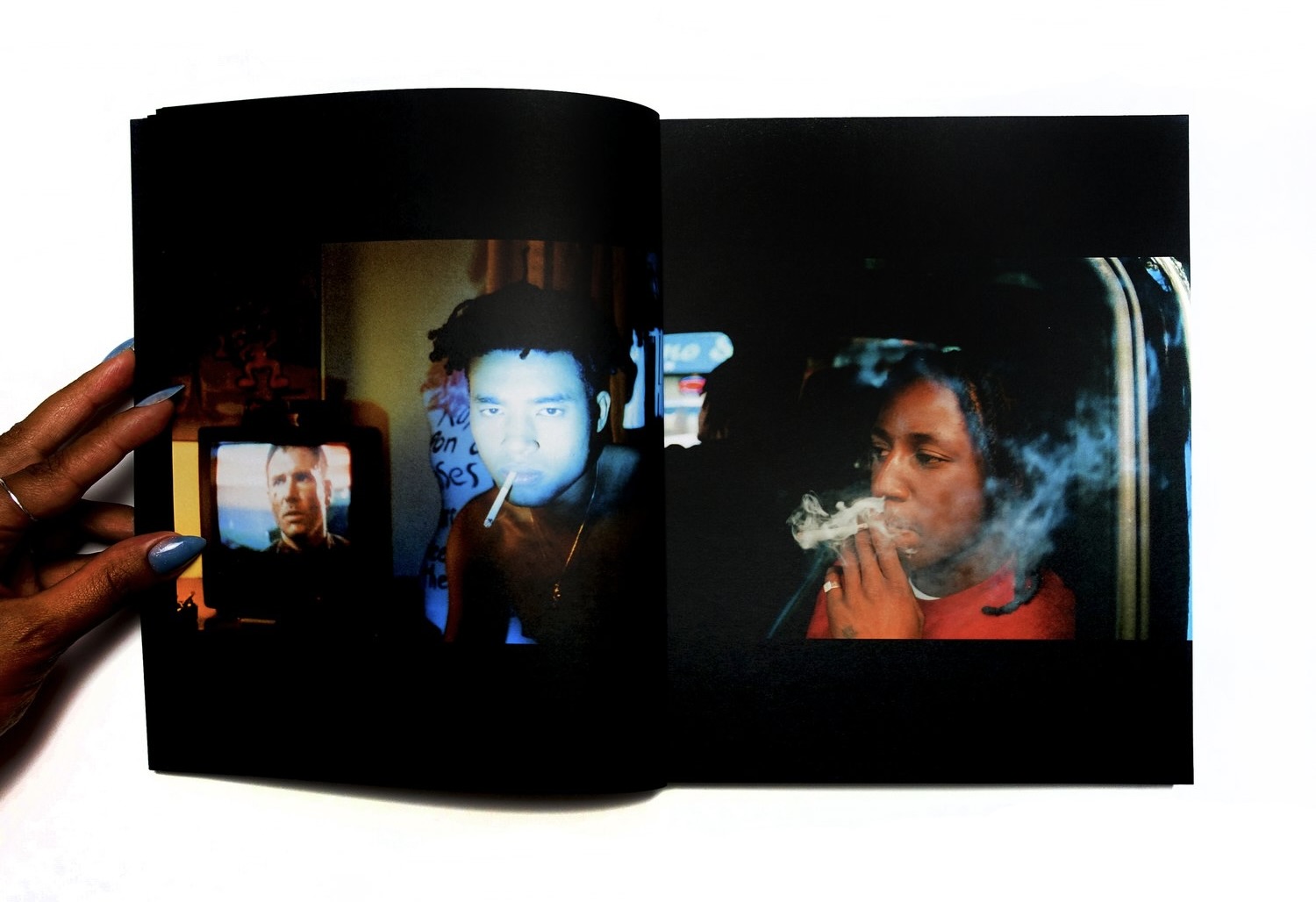

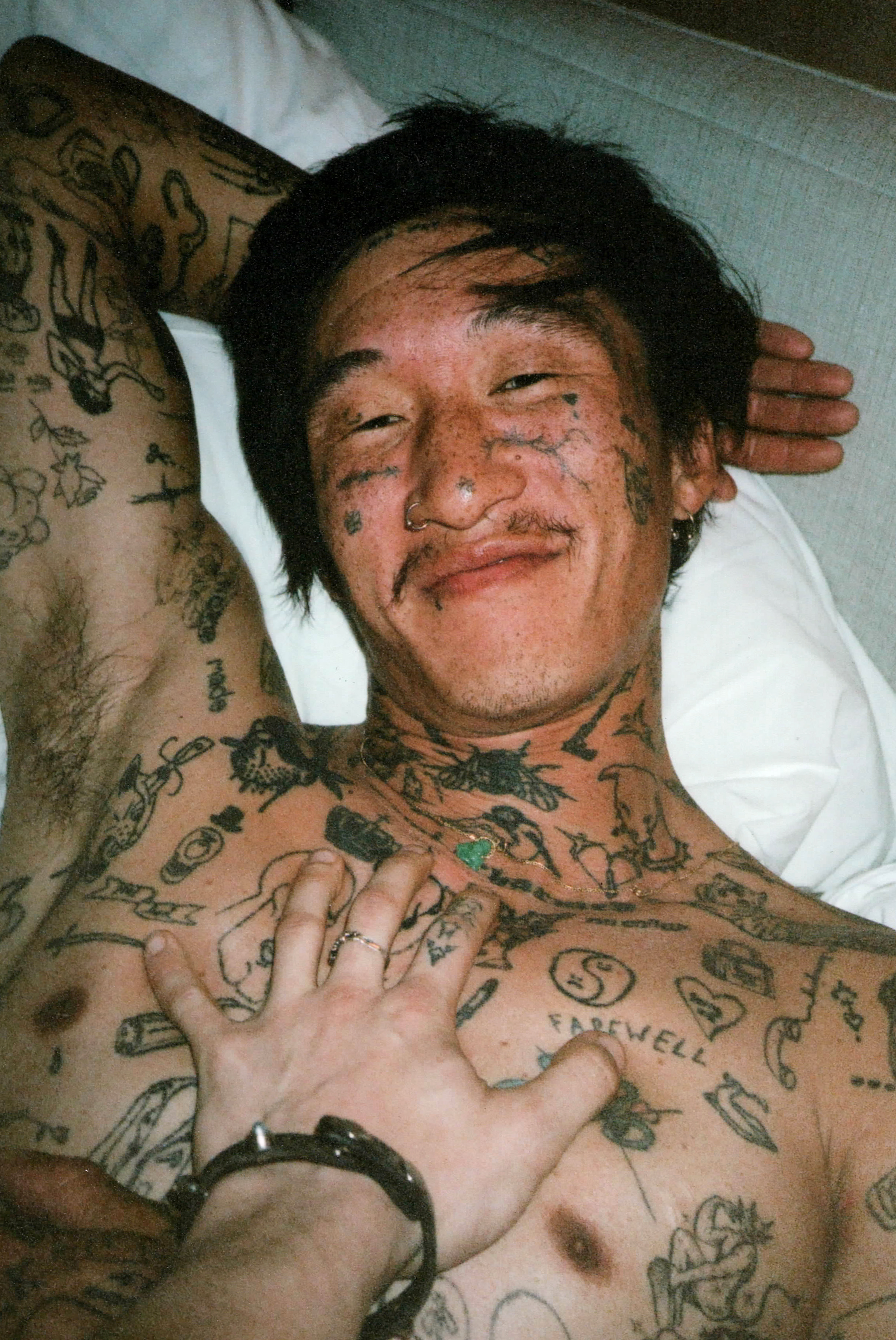

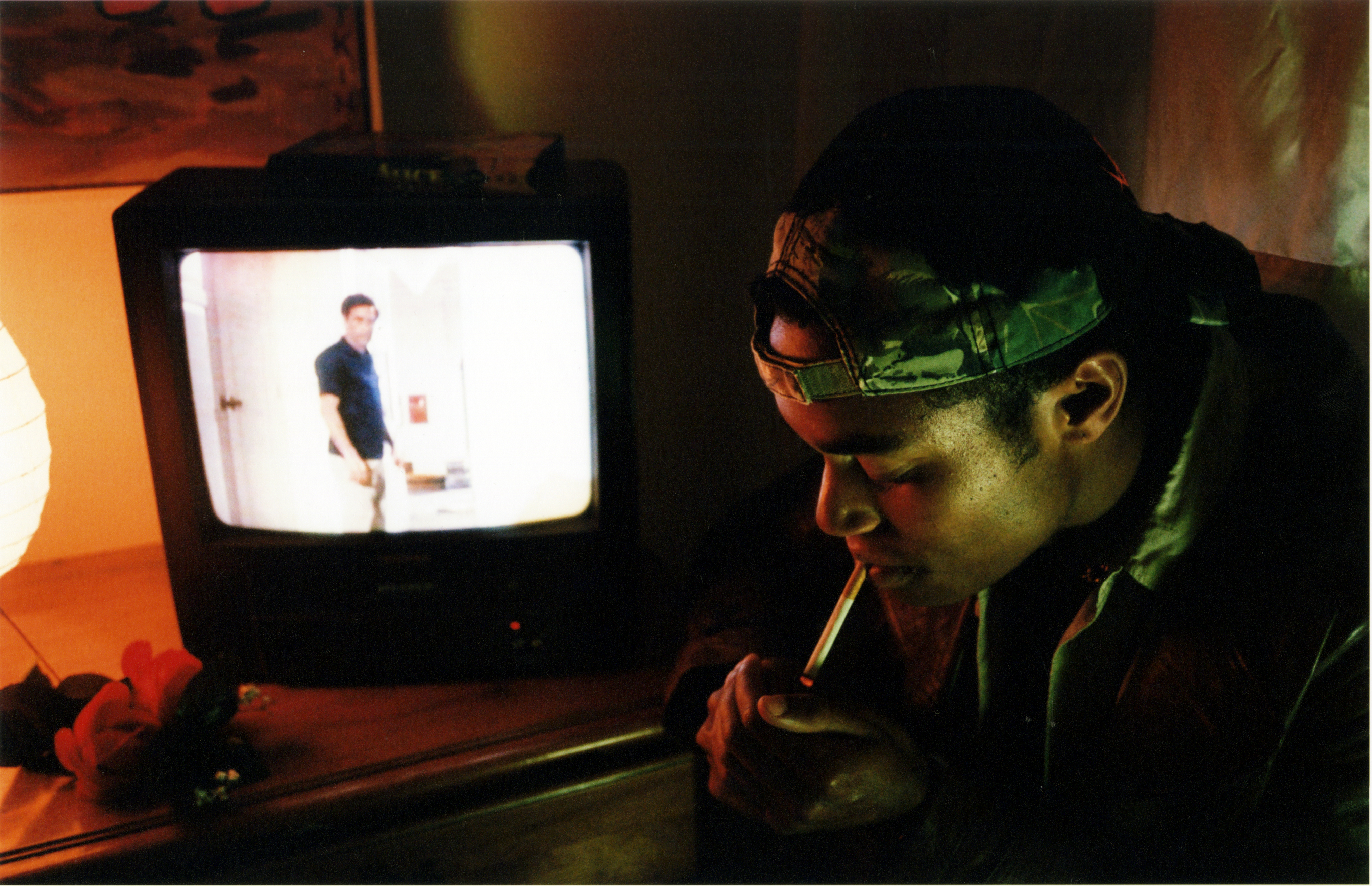

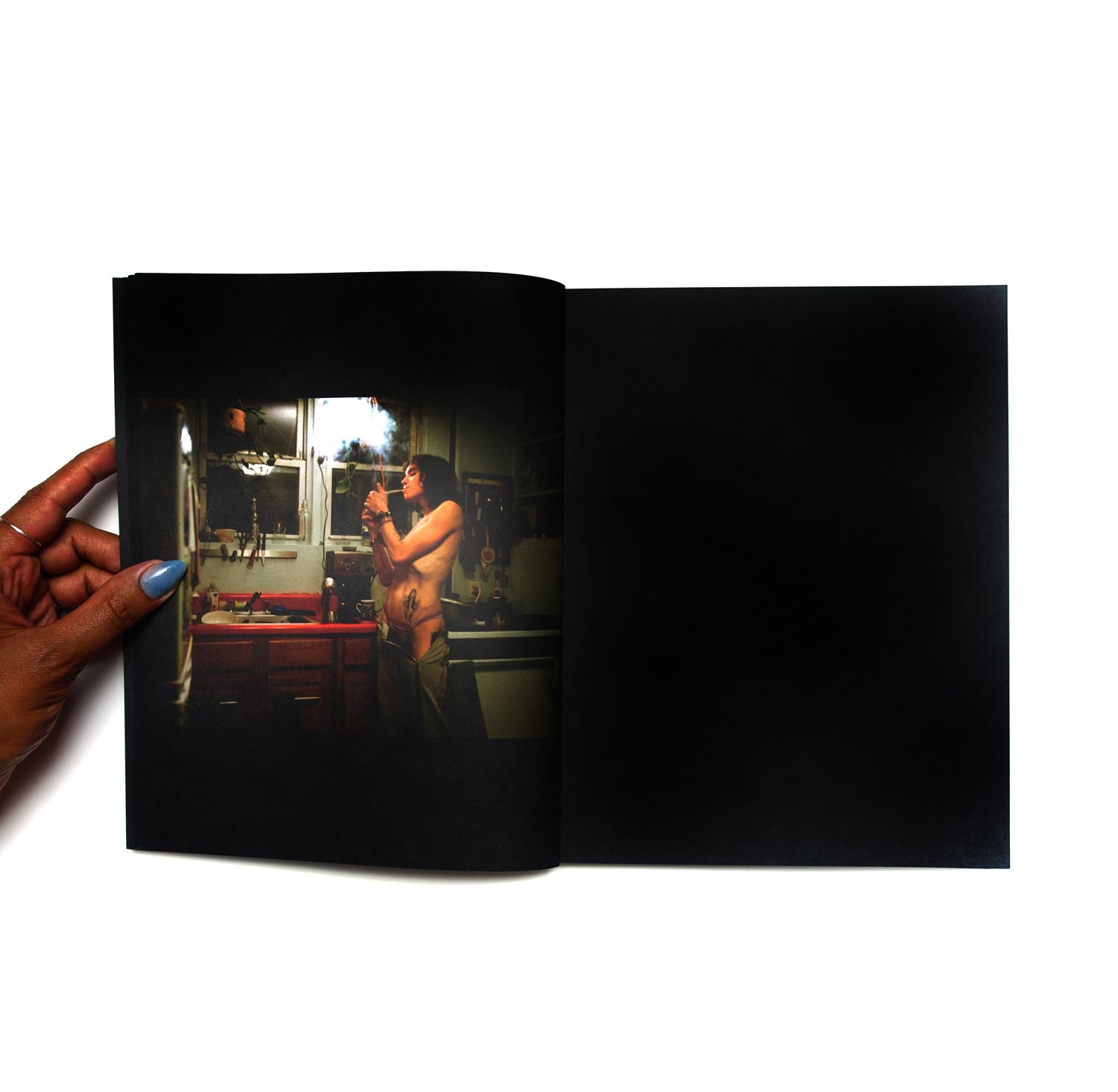

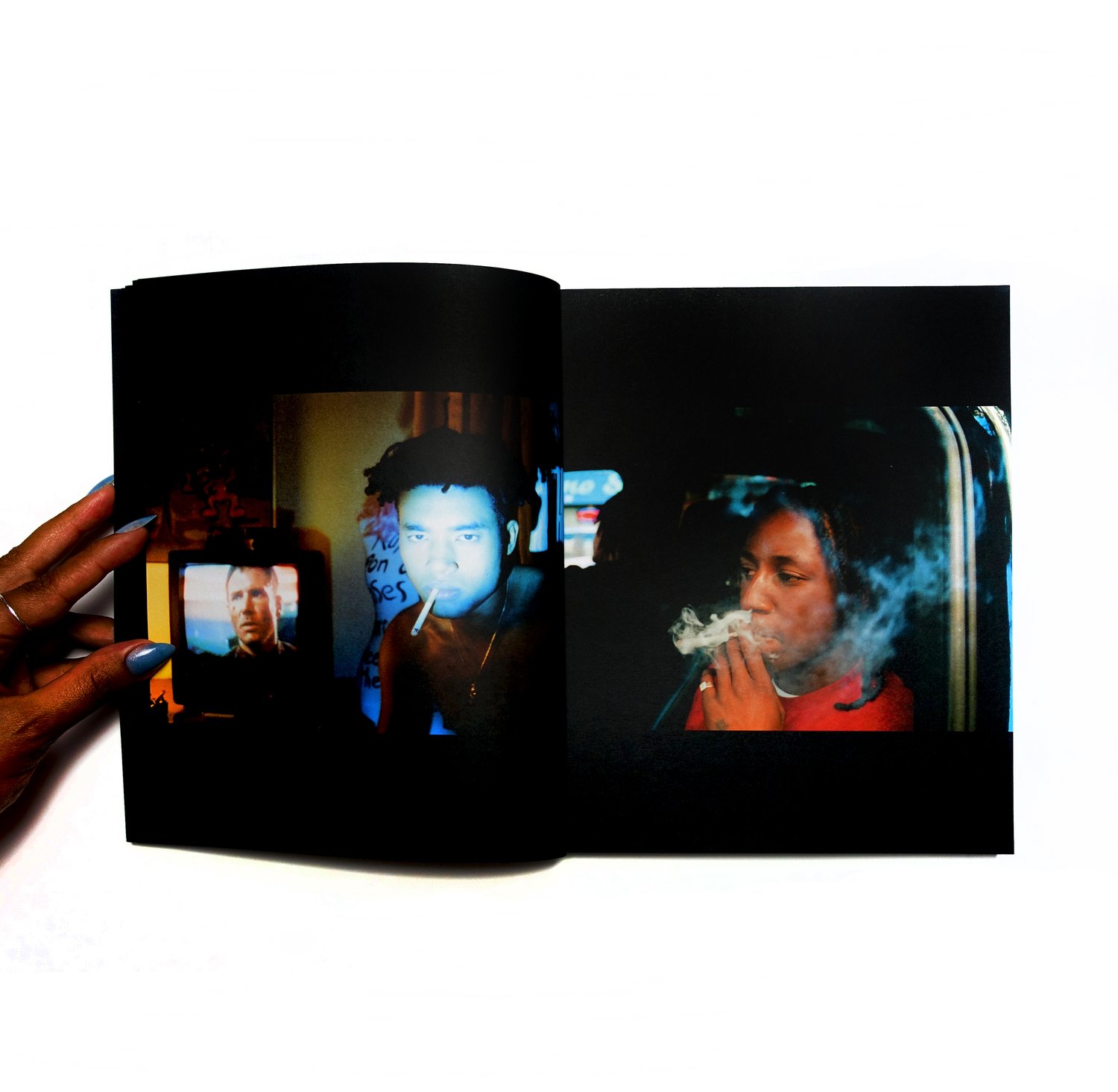

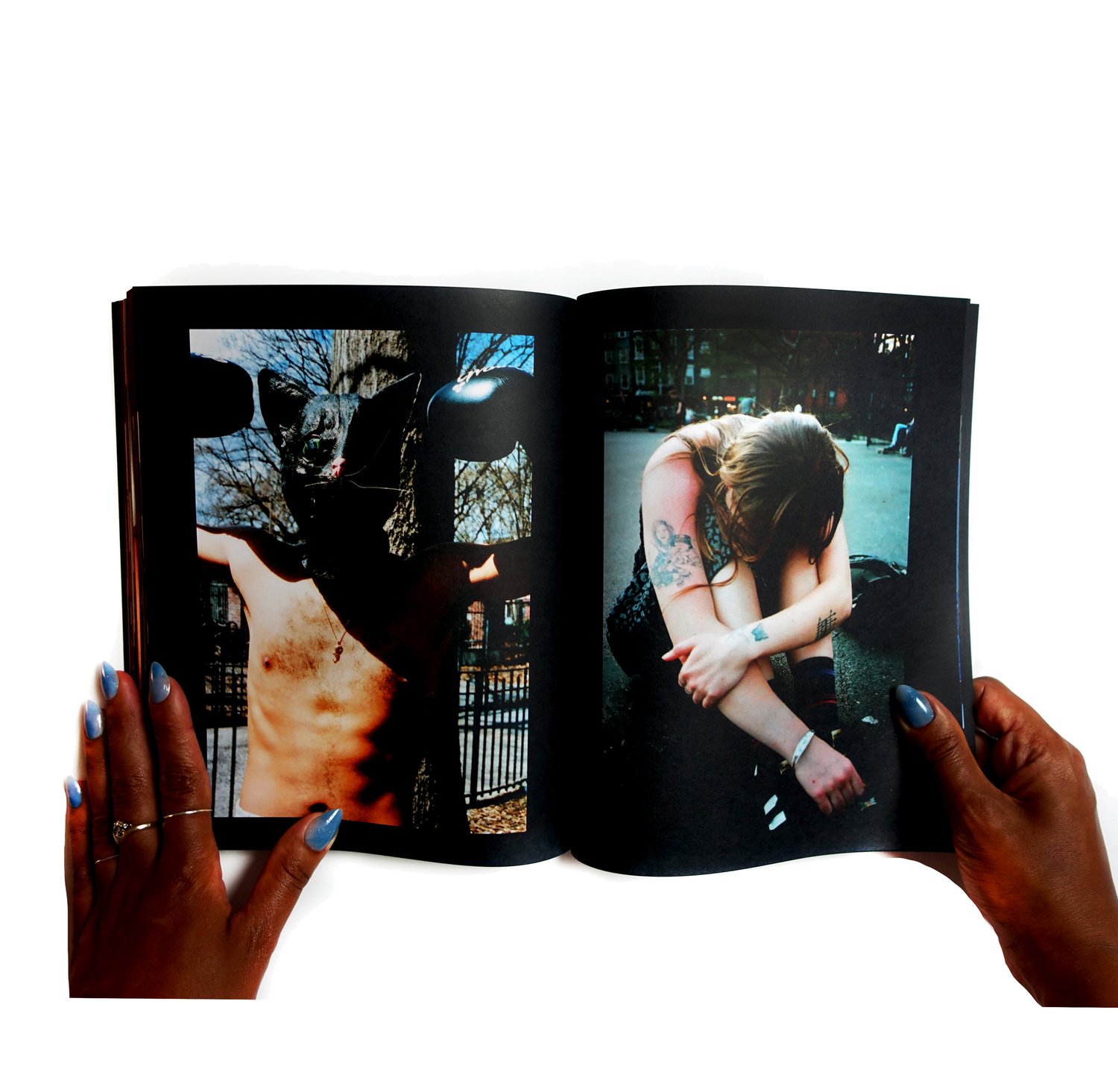

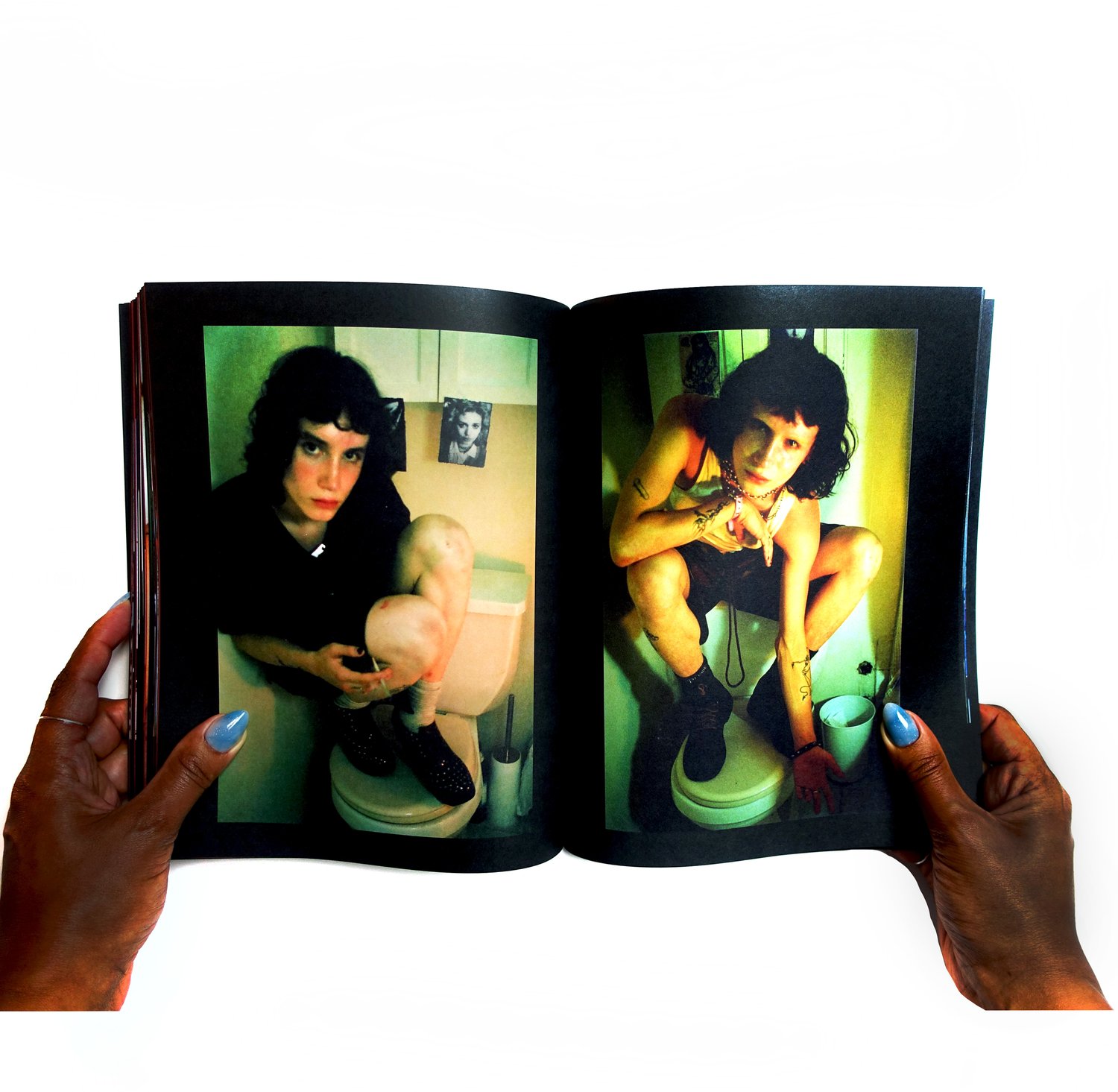

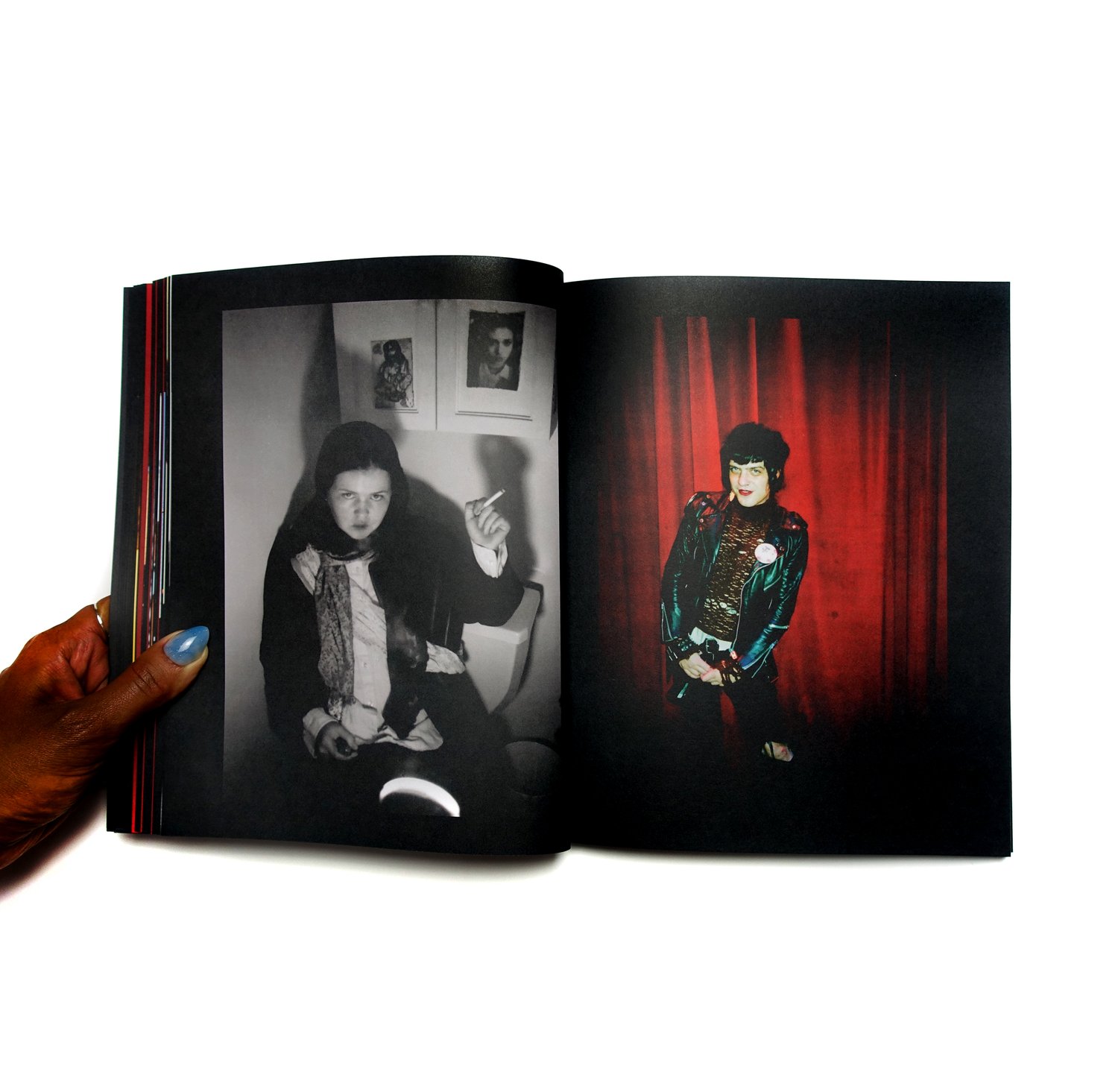

While Danzig also skates, models, and writes poetry, her approach to photography has never felt like a career choice. She takes photos to immortalize the fleeting, in-between moments of her life since moving back to New York from Philadelphia two years ago. Much like Night on Earth cycles through a revolving door of characters, Diary #1 unfolds through Danzig’s tight-knit group of friends. Her love for Jarmusch and filmmakers of a similar style is evident in her use of moody, intimate hues and settings that evoke the cinematic stillness she enjoys.

Below, we dive into the last few years of her life, discussing desert living, sobriety’s impact on creativity, and New York’s generational echo.

So you've been traveling a lot between LA and Paris, what have you been up to?

Efron Danzig— Skating a lot, I was in LA, stopped in the desert where my kinda-boo lives. Then it was back & forth between Paris & New York until now. But I kind of want to move to Paris.

I love being in the desert. It’s nice to not be in a big city.

It's really pretty. Where he lives you have to dig a hole to shit in.

I heard that’s better for you.

Yeah, honestly, it's good for your bowels. My friend has a little stool for his toilet so you're in a squat position and it just comes out smoother. I want to get one, but I think it'll be crazy. People would come over and be like what the fuck is in your bathroom?

[Laughs] So what's inspiring you right now?

Over the past few days, I've been watching Sandra Bernhard on The David Letterman Collection because she reminds me of my sister, and of course, Jim Jarmusch.

What’s your favorite Jarmusch movie if you had to pick?

Besides Night on Earth, maybe Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai with Forest Whitaker.

What do you love about his movies that other people might not notice?

Oh, that's a hard question. I don't know what other people might not notice, but I love the lighting in those films, like the orange and blue Tungsten lights.

Get your copy through Raw Meat Publishing here.

Tell me about the subjects in your book.

They're all people I love. The original incarnation of the book featured a lot more of my friends, but I wanted it to read more like a cast of characters. Like a show where you see the same eight or nine people over and over in certain situations. I wanted people to be able to recognize the characters; if you have too many people, it gets harder to do that. I wanted to capture those in-between moments where maybe nothing even is necessarily happening.

Walk me through a regular day of hanging with your friends.

I love playing pool at the end of the day, sitting in a park, going to a show, riding my bike, the usual shit.

I know you’ve exhibited your photos in shows before. When did you decide to put your photos into a book?

So I met Kyle who runs Raw Meat Publishing, at an Eight Ball zine fair and gave him my email. He hit me up a few weeks later asking to see my photos, so I sent him 50 and he asked to see more. So I sent him 600, and he told me he wanted to make a book. He's made everything easy for me in terms of the logistical aspects, and he allowed me to take my time with this project.

I wanted the book to feel and read like a visual diary or film. I used to write a lot, but at one point, I had a knee injury, so I wasn’t skating and had a lot of time to dwell. That's when I started loving photography as a way to document my life apart from the poetry I’d write.

Does your photography feel like an extension of your poetry?

Once you start writing a lot of poetry, certain things people will say in conversation seem like you have to put that in a poem. It makes you see the world differently and I feel like photography does the same. It changes how you see things, which keeps it interesting for me, but I wouldn’t say it's an extension exactly. To me, they’re separate.

How do you know when you’ve taken a photo you love?

Sometimes you just feel the magic in that moment when you take it, I don’t know. I love people smoking. That's a big part of my life in a stupid way, because I've been smoking since I was young. It's a big social thing for me, so I definitely love shooting my friends at the end of the day when we're just laying in my bed smoking a spliff after a party or when they wake up.

Do you have any favorite moments in the book?

I was sitting inside a car and my friend Kader was skitching while he was on the phone with his friend, smoking a spliff, and it just looked so insane. But honestly, my favorites are the really tender moments where my friends and I are chilling at my house or their place at the end of the day, just smoking. That’s often when I’m like, Can I take a photo of you? And that's it. Maybe I'll move the lamp a little bit closer or something, but it's that candidness I like to capture.

Are you still writing a lot of poetry?

Not as much. Photography works well with skating because you're just out all the time, and when you're with people, you can photograph them. I was definitely writing more poetry when I was playing music; you have more time to dwell… I was drinking a lot too & that helped. I’m 7 months without alcohol now though. Weed and other things yes, but no alcohol. A lot of my favorite poets would always go on about how they were writing when drunk, I don’t know, I would always be drunk too. As soon as I stopped drinking, I stopped writing as much poetry and I've been out skating more. I've realized that I’m not necessarily in a good place in my life when I'm writing a lot of poetry.

Would you say that poetry is a way for you to process more unsettling emotions and experiences as opposed to photography as a medium to document the world around you?

Yeah, definitely. Although I do like using photography to capture loneliness, mundanity, and monotony in my life…. I do write a lot now, but it's more journalistic, very matter-of-fact, recording details about my day or just gratitude lists.

It's so funny that you say that because I feel like I was always writing poetry when I was younger, but I stopped when I stopped drinking as much.

Why is that?

I don't know, but I know we’re not alone. I was reading Maya Angelou’s interview in the Paris Review which talks about how she always wrote in the same hotel room in whichever town she was in. She’d never sleep there and always wanted it to be the same when she walked in. She’d arrive at 6 AM with her notebook, a pen, the Bible, and a bottle of Sherry. She’d start drinking upon arrival or later around 11, and it would get her into the mood.

I don't understand that. I mean, I do understand that, I just don't know why it works that well. I would take Adderall, buy a bottle of wine, sit at my desk, and just drink, write, and smoke for hours, and hours, and hours, and now I can't do that. [Laughs]

Do you feel like your perspective of the world has changed since you've gone “New York sober”?

I'm a bit more of a grandma and a bit more responsible. I feel like it was easier to float through my day when I was nursing a hangover half of it. Now I'm more aware, so I have to figure out what to do with all that time I was missing out on.

It's like your consciousness is numbed out until you start sobering up at 3:00 PM and then you're ready to go. Now that I'm drinking less, I'll go to a boring party and not stay until the end because I can see how boring it is. If you're drunk at a party, you stay a lot longer.

I know, I'll do one of these where I [stands up to emulate walking into a room, looking around, and walking right out]. I've been doing that a lot recently.

[Laughs] I’ve yet to ask if you’re excited to have a book out in the world now.

Yes, I'm so excited because it's my first one. I'm super nervous too, and kind of shy when showing my work, so it's also scary, but I'm excited for my friends to see it.

I noticed that you rarely share your photography on social media. Is that intentional?

It is intentional because, well, I don't do photography as my career. I was talking to my friend who's a career photographer and they have to post their photos in order to get work. For me, it's just fun, so I can choose to not post. And I want my work to exist in a very particular way so that audiences are only able to consume it in that likeness. I used to play in punk bands and I don't have any of that music up on the internet. We would sell tapes at our shows, and it's like, if you come to the show and buy a tape, you can listen to the music.

Everything created isn’t necessarily made for mass consumption.

Exactly, I'm not making it for hella people to see it. I'm making it for you if you care. I like the privacy of not putting stuff onto the internet, and I would definitely share less of my skating too if I didn't have to. I feel like less is more, quality over quantity.

How do you balance expressing yourself through skating with these more personal mediums like photography and poetry?

Skating, it's so different, it's like dancing. It's one of those activities where you do it and your brain shuts off until you're done, whereas photography requires me to think actively. It comes in waves. There are some weeks when I'm hitting up my friends to shoot an idea I have, or taking a lot of self-portraits, and then if I'm skating or traveling, I won't take many photos for a month.

Are there any photographers you admire?

Nan Goldin is one of my favorites. Ryan McGinley too — we use the same point-and-shoot.

I love that you bring up Nan because she's also been in movies herself.

I love Desperately Seeking Susan. I fucking love Rosanna Arquette, she's amazing and Madonna too. She still lived in the East Village back then. That era was so cool. I also love this other Susan Seidelman movie, Smithereens — I love Richard Hell.

Your photography, similar to Nan’s, reflects the community around her, in this very neighborhood as well. How do you perceive the continuity of the intergenerational conversation between these scenes?

That's something I've always been inspired by, New York music & musicians specifically the CBGB scene. When I was a kid, my dad would play a lot of Johnny Thunders, Patti Smith, and Blondie and he put me on to Richard Hell. All of those people have been in my life for so long. My dad was a musician in New York in the nineties. It’s funny because I feel like that scene is still very present in our world now.

It's always in the background in a way. I love it when I'm at a reading and I see Patti Smith or Richard Hell randomly sitting there. I was at KGB Bar and he was there on some random night recently.

Of course he was. The first place I lived in New York was next to KGB Bar. People would tell me that he goes to readings there.

How long have you been in New York now?

I lived here from zero until I was 10, and only moved back two years ago.

Have you been modeling a lot recently?

Yeah, it's been pretty good. I love that shit, it's so fun to be fab, you know?

How does modeling bleed into your perspective behind the lens?

Besides the technical aspects, through doing all of these shoots you learn that when you're with a good photographer, they go out of their way to make you feel comfortable. I appreciate that and I want to make anyone that I shoot feel comfortable too. It's really reflected in the photo if someone is comfortable or not, you can really tell.

How do you get someone comfortable when you’re shooting something more stylized?

If it's a setting up an idea I have, I'll get them a beer. Or, cigarettes if they smoke. [Lights a cigarette]

What was your process for choosing the spreads and the way you placed images together?

Honestly, when I was making the layout with Kyle, we just went off feeling. We didn't overthink anything. We were just like, Oh, that feels like it should be there and this feels like it should be there. We mostly just placed images where we thought they should be.

Do you feel that if you were to release a second book, you'd continue with this diary format?

I definitely like the diary format because it feels comfortable for me, though I also have other little photo projects that I want to work on. I used to take the Megabus every weekend when I was living in Philly, so I started taking a lot of photos of Uber Eats drivers and people in the bike lane. I used to be an Uber Eats biker, I would wait for the bus and take photos of dudes in business suits on their little one-wheelers. I want to make a little zine of silly shit like that, but separate from the diary project.

Your work is an enriched mixture of artistic disciplines: performance, sculpture, painting. How did this hybridization emerge in the first place?

When I started, my very first impulse was to construct exhibitions as sensorial environments for viewers to immerse themselves in. I am greatly influenced by architecture. My first shows were always conceived as site-specific installations, created with the public in mind. I am particularly interested in exploring how to seamlessly integrate artwork into a specific context. I’d say that this investigative process has influenced my own architectural practice. I would create ad-hoc landscapes dependent on, and in relation to, the exhibition space and craft new objects that narrate their own distinct stories.

The idea to work with large-scale sculptures began quite organically, as a byproduct of curiosity. Rather than “just” making an artwork, I had an urge to dissect and develop a situation. The objects themselves look like collections of small, torn-off pieces sourced from various landscapes.

I have implemented performance art since the beginning — I also created costumes, adjacent paintings, and embroidery. I guess this approach is similar to Gesamtkunstwerk, each aspect of the practice serves the same absolute creative vision, one where all elements and disciplines resonate with each other.

What about the references that you incorporate? I particularly like the confluence of heritage and futurism.

Cross-generational references have always interested me. Much of my work involves research — including both aged techniques and heritage know-how. I then source the right people who can help me duplicate and integrate these findings into my artistic practice often topped with modern infusions. I like to take inspiration from our collective memory and mix it with fragments from our contemporary reality. I never strive for historical accuracy; I’d rather create something new.

Klára Hosnedlová: Sounds of Hatching, exhibition view, The 16th Lyon Biennale: manifesto of fragility — A World of Endless Promise, LUGDUNUM — Museum & Roman Theaters, 2022.

Photo: Aurélien Mole. Courtesy the artist; Hunt Kastner, Prague and Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin.

You work a lot with embroidery, which I suppose qualifies as a more traditional technique. How did you first get introduced to the craft and why does it interest you?

The first time I worked with embroidery was during my art studies, but I knew about it for a long time before. At the time, especially in art school, embroideries were not really considered an art form per se. People viewed it as a technique only, either used in the textile industry or as a domestic activity, and I quite liked that. I think it has to do with my need for intimacy. This categorization outside of the fine arts framework made me feel comfortable. I never felt any pressure to master the craft. For me, it is a tranquil practice that creates this meditative sphere where I feel free to create.

I’m curious about the visual connection — I read in another feature that your embroidered pieces often are based on photographs. Could you share more about the process?

I would say that the workflow is quite organic. Usually, my embroideries are based on photographs from previous performances. So in most cases, the current exhibition includes references from the one before. I think of it as an endless circle, where all the artworks relate to one another. My work addresses themes of memory and replacement; it fulfills a need to perceive everything from a wider context and make new connections.

Klára Hosnedlová: To Infinity, exhibition view, Kestner Gesellschaft, Hanover, 2023.

Photo: Zdeněk Porcal - Studio Flusser. Courtesy the artist; Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin and White Cube.

You mentioned performance art before. It’s interesting how each performance targets you and your performers, but also heavily emphasizes the audience and their own involvement.

I think it’s important to explain that my performances are not open to the public. They are always conducted in advance, even before the actual exhibition opening. Once an exhibition opens, each performance is relayed through pre-recorded documentation, usually a mix of photography and video. However, the audience is encouraged to navigate the space in a similar manner as the performers. I want them to walk in the same path, yet bring their own presence and traces to the installation.

For me, the dialogue between performer and environment is as important as the dialogue between audience and environment. I don’t request the installations to be “protected.” Once they are open to the public there are no barriers or limitations. Essentially, you can walk on them if you like. It’s not uncommon for visitors to step on a piece of tapestry or an epoxy puddle as they navigate through the show space. And that is fine. I really value the viewer’s freedom to circulate with full integration in the environment. This is crucial to me. It resonates with the whole idea of exhibition as an experience, to blur the long lasting hierarchy between artwork and scenography.

Your recent exhibition GROWTH at Kunsthalle Basel provided a form of commentary on time, as it linked our past, present, and future society, while it also addressed the fine line between dystopia and utopia. Could you explain how this idea came about?

I rarely develop any personal themes through my work. I’d rather provide a commentary on society based on ordinary details from our everyday lives. Take, for instance, the motifs of the embroideries. They depict situations where a performer manipulates quotidian objects which we’re all familiar with, like smartphones or UV flashlights. By purposefully ignoring the sophistication of these objects, I reduce them to their purest form and empty them from their function. I want to shift the focus back to the human figure. If there is any melancholy attached to these images, it is not meant to play on either dystopia or utopia. It has never been a conscious intent, at least. Actually, I particularly dislike when people label my work as post-apocalyptic. I am more interested in the individuals themselves and the emotions involved when we are confronted with specific aspects of society.

What lies ahead? Any upcoming projects that you can share with us?

Right now, I am preparing a solo show for the Historic Hall of Hamburger Bahnhof, which opens in 2025. I am also preparing an exhibition at White Cube in London.

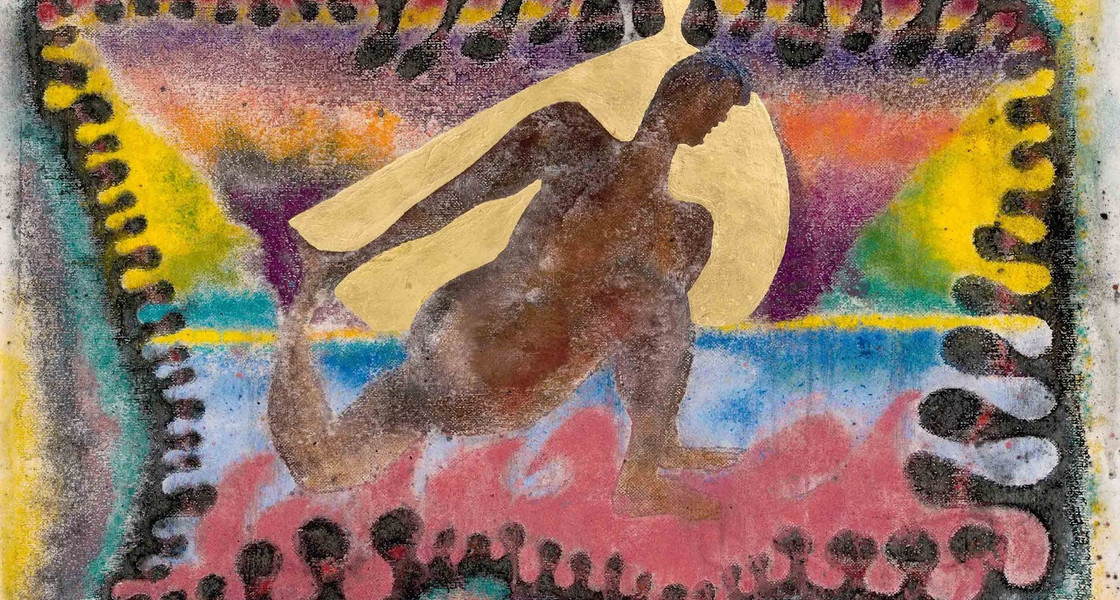

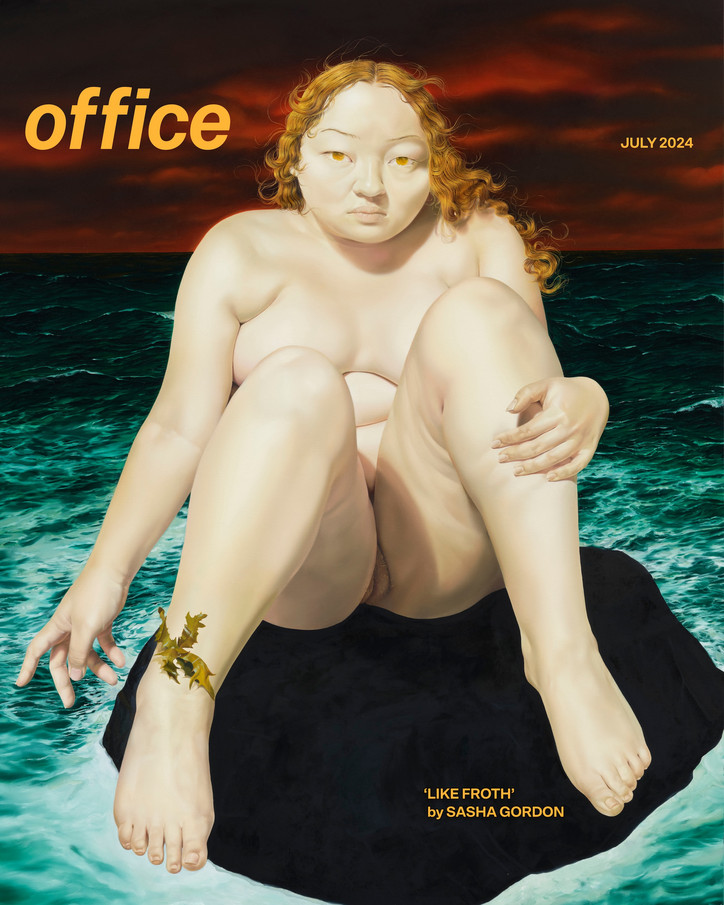

Her debut solo museum exhibition “Surrogate Selves” opened last December at the ICA Miami, merely the latest in a string of solo and group exhibitions she has participated in since graduating from the Rhode Island School of Design in 2020. Few other artists of her generation have managed to achieve what Gordon has, much less so quickly. “People really relate to the paintings,” Gordon says of her success, looking a little dumbfounded. “And, honestly, it's kind of bizarre to me.”

Raised in Somers, New York by a Korean mother and Jewish Polish-American father, Gordon often felt like she didn’t belong in the community around her. “I felt very isolated,” she describes. Finding solace in a series of creative pursuits from crocheting to sewing to fashion design, Gordon would eventually find herself driven by what she calls a “subconscious curiosity” about the medium of paint. By the time she entered high school, she had started to develop a level of technical skill and precision far beyond her years. As she honed her craft at RISD, her works began to catch the eyes of professors and collectors.

Gordon’s singularity lies in the visual language she has been able to develop for herself. In an age where we are all subject to a constant and overwhelming barrage of imagery, Gordon has been able to stand out from the noise. Whether one is familiar with Sasha Gordon's work or not, one can recognize the common language between her paintings the same way one can hear a foreign language and recognize it without speaking it. According to Gordon, she developed that language for herself as she left her hometown and grew into her own independence and selfhood. “I think I was really basing my paintings on how much skill I had,” she says of her earlier work. “In the past few years, I used the skills to translate storytelling and narrative and feeling. I had some great professors [at RISD], and a lot of them were telling me to be looser. I’m a very uptight detailed person and I still am. There’s a way of keeping that but still inventing something new, rather than painting something as realistically or as close to the reference image as possible. There's so much you can do with paint. It’s limitless.”

'Something We Said', 2024 'Untitled', 2024

But more compellingly than their technical perfection, Gordon’s paintings are able to evoke the inarticulable and constant discomforts of daily life, emotion, and interaction. “The work is really earnest,” she says, “and that’s because I put whatever I'm thinking out there. I can’t think too much about who’s viewing it.” The effect of her paintings is inextricable from the sense that one gets that Gordon is still painting as though she is alone in her room in Somers, New York. Now that she has had some distance from her childhood, Gordon says she is able to enjoy the scenic nature of her hometown when she visits. “It definitely makes me appreciate my life now a lot more, just because of how alienated I felt growing up,” Gordon says. “I really value my community here [in New York City], and my artist friends.”

One such artist friend is fellow painter Amanda Ba (b.1998). Both born on the cusp of generation Z and part of what Ba refers to as a “small network” of Asian American figurative painters in New York, Gordon and Ba became close in the last few years but have known of one another through social media for much longer. Ba’s studio is in the same building as Gordon’s, and the proximity of their workspaces allows for hang-outs and informal studio visits with a rare level of frequency.

When Ba walks into the room, she immediately takes note of the plant cutting on the coffee table. “The Pothos grew!” she says, settling into a chair across from Gordon. For the next hour, the two painters trade nuggets of wisdom as they pass yellow American Spirits and a bowl of strawberries between them. We discuss the machinations of the art industry, the influence of their hometowns on their art practices, outsmarting identity politics, and so much more. Read our conversation with Sasha Gordon and Amanda Ba below.

How did you two meet? Did you encounter one another’s work before meeting?

Sasha Gordon— I found you [on Instagram] around the end of high school. One of my old friends showed me Amanda’s work, like “Oh, I think you’d like this girl’s art.”

Amanda Ba— I definitely saw your work online before I ever met you in real life.

SG— In high school, I wasn't familiar with any Asian artists, or any artists of color. Then in college, I did my research, and I saw some established artists that dabbled in really similar stuff as me. But seeing someone my age was just really important; we're both coming up in this kind of confusing art industry and world. And I thought she was so talented.

We didn't meet [in real life] until, like, three or four years ago, because we were both in college.

AB— Yeah. And we were always friendly, it was just sort of this distant observation until we met and got closer.

Before showing in a gallery, I didn’t really have a very concrete sense of how things in the art world operate. I painted progressively more as I got more into my major requirements towards the end of college. I think we were both experimenting with a lot of different styles.

SG— Yeah, we don't paint the same way as we did then. Not at all.

AB— No, not at all. But yeah, I mean, it was sick to see someone doing really well, whose work I identify with. And it was good motivation. Not necessarily competitively, but just motivation; you see someone else's work that you really like, and you're like, oh, I wanna do better.

I think that as we grew up, entering the art world, or just becoming more familiar with it, it became more important to actually make note of other artists’ work. When it comes to Asian figurative painters in New York, we probably know most of them either peripherally or we’re friends with them. It's just a small-ish network.

You both had this experience of entering the art world — to use your word, Sasha, the art industry — at quite a young age, and have experienced a rise in visibility for your work rather quickly. But you’re also both still young, and still growing up. Typically the art is thought to reflect life, but how much do you think the forces of the art industry are also influencing your lives? How much does that then show up again in the work?

SG— I don’t think anyone’s ever asked me this before. I feel like [the influence of the art industry] is pretty constant. I'm having at least a few studio visits a month, and talking to other artists, and seeing galleries, and I try to stay up to date with other painters. And then there’s art fairs.

AB— The fairs are the only thing that resembles an office or work environment.

SG— Yeah, it’s really bizarre not having a set schedule. The art fairs do kind of make a replacement for that, the fairs are when you become social. Otherwise, it’s quite an isolated job.

AB— Scheduling in the art world definitely dictates the pacing and the work-life balance of your year. And for example, my show is set up to coincide with the beginning of the art world season in the fall, and art fairs like [the] Armory Show…

SG— Frieze too, there’s a bunch of art fairs. That’s so true.

AB— And they all happen around the same time as fashion week. If anything, actually, the broader world is always on a school schedule. Everything starts in September.

What about its impact on the pace of your production?

SG— I feel like there hasn't been one show where I’ve had extra work, or finished on time. Almost every due date I've had, I've pushed by at least a week or two.

AB— It’s on us to agree to the deadlines; we decide how much of a workload we can manage within a very long time. And it's bizarre to think about a project that could be a year or more away, and how you're going to keep yourself paced during that time. But there’s nothing else dictating our work time.

If we had time to just chill with paintings and experiment with no deadline — I actually have no conception of what that might be like.

SG— Right. It's so weird also, because you never know how long something is going to take. So I feel like you sometimes have to grind just to be safe.

[The pacing] definitely helps me, personally. I think it pushes me to work in a different way than I'm used to, and I learn a lot from that. I can get super obsessive, and if I didn't have a deadline, I could probably work on one painting for eight months.

Now, I've gotten way more accustomed to the schedule of things, and there are some moments to be expected where the end result might not be exactly how I pictured it.

In the last several years, there has been a massive uptick in fascination and interest with “artists of color” and “marginalized” artists, which has also been coupled with a very exploitative model within the art world that can reduce people to just their marginalized identity. How are you thinking about navigating that in your work now?

SG— I remember a professor I had, who is a Black queer painter, and we were talking about this topic. She was saying that she paints Black figures, but she doesn't feel like she needs to explain it or go into such detail about it, because she just exists as that.

That really struck me, because I was doing more work about identity a few years ago, when I was discovering a lot about myself and was reflecting on my whole childhood experience of growing up in a white community. I think it was important for me to make those paintings, I definitely go back to those paintings a lot, and sometimes I find the paintings I'm working on currently have more to do with identity. But I don't feel like I need to talk about it in every interview or every artist talk.

I think the paintings have more to do with the psychological effects of that experience, not so much being Asian or [asserting] that representation is so important.

AB— I love talking about this topic. I think that what your professor is getting at is, why aren't we ever questioning paintings of white people? Why is it not shocking to paint them? It's a given, it’s not a big deal, and therefore it's omnipresent, but it's not the focal point, right? It's just part of the experience, part of a continuum.

SG— If you paint an Asian person, it’s like, “look at this Asian American painter Amanda Ba!” But would you ever say, “look at this white painter?” because someone painted white subjects?

AB— The natural, intuitive motion is to insert people that look like us into the canon. The goal isn't to, like, recognize Asian people. The goal is to have images of people of color be treated as commonplace.

I don't know if we'll ever get to this point, but if there was a more adequate sense of representation, maybe we would then have the freedom to go and, like, become minimalist sculptors or something.

SG— That would be awesome. [Laughs] I mean, it's cool sometimes when I see artists who don't have any take on identity, and just make beautiful images. That must be nice, to not have these ideas assumed and placed on the work in the way that it happens to us.

AB— It's also about how much responsibility you feel and want to take on, and then want to project out into the world. We totally have every right and reason to say fuck all, and make work that’s maybe even devoid of figures. But I think it's also about complicating identity to a point where it's less easy to explain. You can't just indulge yourself in your own intentions or whatever; you have to be aware of what is always out there.

So how do I outsmart that in some way? Can I make the painting so complicated that they have to think about something else?

You both grew up in places that were not major cities or considered hubs for art, and I’m curious how you think that affected the development of your practice. Had you grown up in New York City, do you think your practice would be different?

AB— I have no idea what it would be like to grow up as a teen in New York. That really perplexes me.

SG— I heard there's almost too much freedom. I can't imagine. I was so sheltered and had very limited resources compared to what I have now living here. I feel like… maybe I wouldn’t have painted?

AB— You might have just been having fun, partying.

SG— I also think being sheltered definitely made me. I had to learn a lot on my own. I didn't have access to what I wanted, which was more of an art scene. So I kind of had to do my own research by myself, and really spend a lot of time practicing the craft and building up that level of skill.

And if I didn't have that transition, from growing up upstate to moving to Rhode Island and then the city, I don't know if I would have come to all these solutions and conclusions of my experiences and my identity. Making this more narrative work — I don't know if that would have happened.

Do you ever have informal critiques with each other?

AB— Every time we see each other is a little bit of an informal crit.

SG— Sometimes I need a second opinion. I don't always take the advice, but I like to hear it. I definitely value what Amanda thinks of my work, so I want to hear her take on things.

AB— Yeah, same. I feel like sometimes I come to you and just ask, like, “what color?”

SG— We'll show each other like artists we like. We're constantly looking at Lisa Yuskavage’s work together — you can tell when we were starting a painting, and we pulled up Lisa’s website.

AB— Painting, at least the way we paint, is harder to critique and then go back in and change something drastic. But we are catching each other at stages where there’s actually a decision tree, a fork in the road: this way or that way.

SG— In college, critiques were our main way to get to talk about the work and run ideas through people. It was an adjustment to move to the city during COVID and not have anyone see my work or get to talk about it. And it's nice to have studio visits, to be in the same building with Amanda — we call it school, it almost feels like camp or something.

AB— We hang out as friends, but if we're hanging out in our studios, the work is always peripheral. You know, I think your studio is the only other studio I see so consistently, like multiple times a week, steps and steps of progress, talking to each other about color palettes, and compositions.

SG— Yeah, it's really nice. We can visit each other and it makes us realize there's like a bigger world out there than just our studios.

AB— Friendly competition is so helpful to me, too. It's just like, wow, this person made something amazing, and I want to make something better. The speed of the art world makes you feel this way, but it's not this limited set of ranked spots. The goal should be to expand. When I see someone make a really great painting, I'm like, fuck, I wanna go back and make a really great painting.

SG— I remember we were talking once about some artist, and we were both, like, almost jealous of them. We were really critical of their work, but I think it's because we were so moved by their skill and technique. It's so cool to like, keep in touch with all these people, and see what they're up to — to motivate each other with each other.

Sasha, a while ago, you said that you were curious to see what the work would look like if you weren't showing. Have you had a long enough period to actually get to see that? If you did, how do you feel that the work has changed?

SG— I don't think I have. There was the first show I had, I had like a year and a half, and that was actually kind of challenging. It was during COVID, so pretty much no outside opinions, or advice. Recently, it's been like I’ll have a show and then I’ll have 5-7 months ‘til the next, and I don’t really have time to… I think I said I wanted to make “ugly” paintings.

AB— What about this one? I feel like this is the only one. [Points to a painting on the wall]

SG— That’s true, this is the only one I did because I was a month into dating my partner and it was a present. And that was fun! I feel like it's looser and smaller and there's no expectation.

I constantly want to make better work, and I feel like I've set up a certain standard for all my paintings having insane detail and huge scale and new innovative ideas. It has been hard to do, but every now and then I get a chance to try to make something weird. I don't have to show it or display it, I just keep them. I definitely want at some point to have a full year to just make stuff with no goal of showing any of it.

I actually will be going to Italy in October for a residency, so hopefully I can do some more exploration then. I went to Rome once to study abroad, and I also changed a lot during that period. I think being away from the city, and other artists and friends, it just inspires this freedom to fuck around.