Welcoming the New Year with David Zwirner

For more information on the exhibitions or to make a gallery appointment, visit David Zwirner here.

Stay informed on our latest news!

For more information on the exhibitions or to make a gallery appointment, visit David Zwirner here.

Bolding’s attraction to gestures of chance and accident can be attributed to his close studies of the highest arena of 20th century German cultural wars, where deskilled conceptual painters like Jutta Koether and Charline von Heyl, closely associated with the underground art scenes of Cologne and Dusseldorf, vigorously attacked conservative representational regimes within the established art world and quickly ascended into stardom. The lyricism and collaborative impulse found in Casey’s paintings could be traced back to Milton Avery, whose fondness for unrestrained use of colors and expressionist figuration lifted the American tradition of abstraction out of obscurity and into European museums. But perhaps the most fascinating of all of Casey’s influences is the most lowbrow: his time spent working for his uncle’s faux finishing company that covers the plain walls of middle-class households in Colorado with Tuscan style decorative patterns.

When Bolding invited me to his solo exhibition, I went in with a reluctant curiosity, as I have been a fan of his practice for a while but remained wary of how art history tends to monumentalize white male painters and mercifully allows for their self-mythologization. After an hour, I came out of the meeting with a completely different understanding of Bolding’s position within the art world. He is candid without being contrarian and sincere without being pretentious, seemingly propelled by a tender attention to social relations and concerns that often fall outside the priorities of the New York gallery circuit.

Bolding professed that he never quite anticipated the level of success he would have today. Coming from a suburban town south of Denver where “very few people had the resources to make it out,” Bolding’s upbringing foreclosed art school as a possibility. “No, this is crazy,” was Bolding’s instinctive reaction when he heard for the first time how much art school would cost, “I am not going to enter my adult life with a huge amount of debt.” Though he admits to being “untrained in some ways,” Bolding still insists that he could never claim to be an outsider. Indeed, it is perhaps more accurate to say that Bolding is a self-taught artist who has been rapidly pulled into the inner circles of the art world after nearly a decade of receiving little curatorial attention. After a group exhibition at Mammoth in the summer of 2023, Bolding was selected by artist-turned-gallerists Ted Targett and Anna Eaves for another group show hosted at Shoot the Lobster in late 2023. Soon after, he was approached by dealer Polina Berlin for a studio visit and she offered his first solo show.

Upon graduating high school, Bolding threw himself into the graffiti and skateboarding scene in Colorado. Trains were his main target. Seduced by New York with its more robust graffiti scene, Bolding moved to Brooklyn in 2013. He made a living by working at a print shop in Williamsburg and freelancing for various mural projects. Developing his practice in his free time, Bolding would spray paint graffiti inside abandoned buildings, where he did not have to “fight for space or worry about trashing some pieces of New York history.” When I asked Bolding if he was thinking about the validation of art institutions, Bolding maintained that he just felt like he needed to paint, given his access. “I often ended up with a bunch of materials from my uncle that would otherwise go bad,” he says.

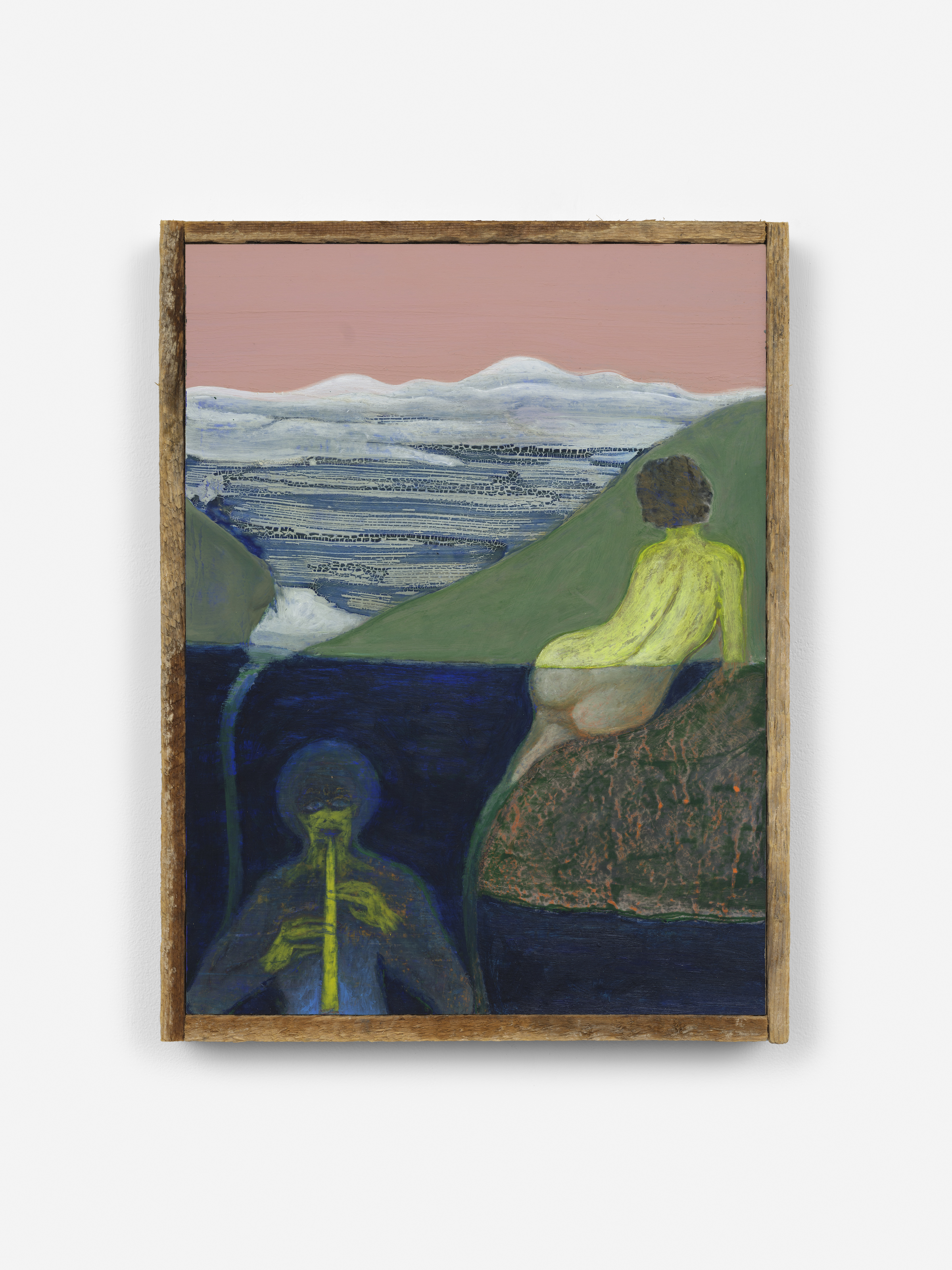

Bolding’s style is indebted to graffiti culture and his years spent painting economically, and it manifests clearly in his works. In some, traces of paint dripping down are visible and exposed, and textured surfaces give the impression that these paintings were just scraped off a wall. At the same time, Bolding tries to veer away from the literal and explicit communication of graffiti, instead choosing to convey a psychological landscape that is ambiguous and ambivalent. Haphazard torsos blend into the background, twisted, bent over, and charged with tensions. Faceless, out of focus figures recur and turn away from the gaze of the viewer. Rare cases of frontal figuration are troubled by their ominous double.

In Bolding’s paintings, I also sense a thin veneer of otherworldly time. The kitschy, rustic feeling of faux finish is transformed into a poetics of unpristine sedimentation that takes on a durational element. Working with photographs — sometimes of family members, and sometimes of random children on the streets of Lower East Side — that have a particular temporality, Bolding’s brushstroke transforms them into moments of disquietude and pleasure, evoking universal archetypes and sitting outside of time. Mulling over these appropriated images intensely, Bolding’s constantly applies layers of oil, acrylic, flashe, and plaster on his canvases and then strips, sands, and trims them away, with the intuitive conviction that the source of the image becomes all the more effectively clear in this process.

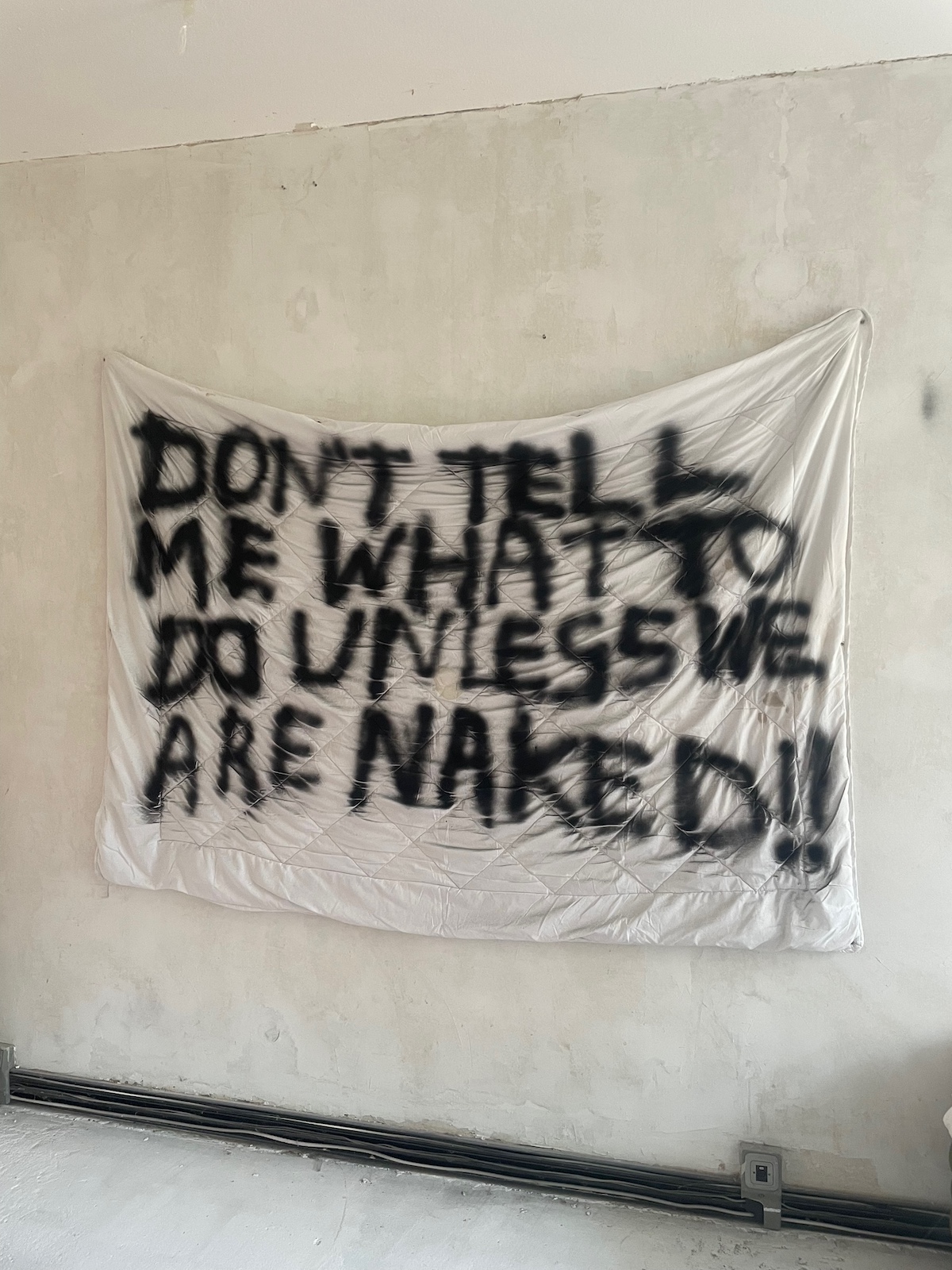

Bolding can be quite sentimental about the objects he has collected and the people he has encountered. Yet, he does not seek to glamorize — or celebrate, per the tradition of portraiture painting — everyday life; rather, he favors a guerilla and confrontational approach with the immediacy of lived experience. In one painting, Bolding grapples with the nature of remembrance, using an Ikea bedspread as a tactile site of information both condensed and lost. Working with a former lover that is now no longer present in his life, Bolding hung the comforter on the wall and put a sheet of plastic over it. Together, they painted directly on the plastic,and then ran across the room to transfer the paint from the plastic sheet onto the actual canvas. While the details of the event cannot be recounted from merely viewing the work, traces of the co-creation can still be felt. In fact, this is one of Bolding’s favorite ways to paint. “I like finding shortcuts,” he confesses “I want viewers to look at my painting and feel like they can do it too.”

Bolding is looking forward to keeping painting and working with galleries, but he also anticipates more time spent with graffiti friends on murals. That isn’t to say he does not care about the allures of art world glamor and commercial success; rather, these achievements allow him to focus on what he truly wants and needs to do. The afternoon when we met he was in a well-worn t-shirt with exposed seams, several holes, and spots of paint residue, a perfect witness to Bolding’s personal history as a devoted painter. That t-shirt felt partially illustrative of why Bolding enacts the desire to paint — to document his devotion to painting itself.

And it is in fact the very idea of abstract interrelational experiences that comes to mind when strolling through the exhibits within the three separate rooms of Villa Clea. The Ritsch Sisters seem to have approached the architecture and interior of Villa Clea with precise playfulness, as becomes evident in the first room of the exhibition. Against the backdrop of a minimalist sound installation featuring the sounds of birds from New York and Vienna combined with occasional piano notes, we see photographs mounted on curved aluminum plates, which engage in a respectful dialogue with the space and the spectators. These sculptural photographs seamlessly blend into the organic monomaterial construction, which largely consists of light curtains, mirrors and aluminum furniture. As they either face or turn away from the viewers, they create a captivating interplay of proximity and distance, resulting in a wonderful ambivalent experience between concentration and spatial dispersion.

The second room shows a video installation titled Sound of an Egg Peeling, a symbolically charged exploration of human interdependence and connection. German-speaking viewers will likely notice the phonetic similarity between the English eye and the German Ei (egg). Might this be a meditation on natality and the Ritsch Sisters’ shared fascination with the seeing eye? In any case, eggs scattered throughout the room (sourced from a neighboring farm) create an immersive encounter, especially when visitors start peeling one of those eggs themselves.

In the third and final room, we find ourselves standing in front of a bed over which the largest photo print of the exhibition looms, titled Full moon she thought. It shows a woman with half-open eyes gazing at us from a potential delirium. Or is she annoyed that we disturbed her in her private bedroom? Those who don't fall into the bed at this point can turn over and enjoy getting their hands on the publication Together Apart by the Ritsch Sisters, which was published last year.

Immersive and fluid

For Villa Clea, Matteo Corbellini has used the remains of an old body shop to build a new architecture made of clay and concrete, while Allina (Alessandra Pelizzari Corbellini) designed the puristic and clear interior. Together, they have created an immersive and fluid space where they live, offer art residencies and aesthetic experiences, in a community centered around contemporary art.

When I hit up the artist that I’d followed for so long — and thought I knew — he was en route to the Italian countryside, where there’s no internet. We discussed his decision to delete his account, his recent show, and his plans for the future — that is, for when he returns.

To a lot of people on the internet, including me, you’re known as Maison Hefner. But you recently deleted the account that I and everyone else was following in order to go by your real name, Monty Richthofen. Tell me more about that.

Monty Richthofen— I first started using social media in 2015. At the time, I had just moved to London and started tattooing. My friend Joe Fox told me that I should get Instagram to promote my work. I wasn’t really into the idea of social media and didn’t have a smartphone, so I asked him to make me an account. I was living and tattooing out of a tiny attic but I thought it would be funny to have a username that implied something different. And that was the birth of me posting tattoos on a cracked version of Instagram on my Blackberry.

But I see “Maison Hefner” as a character from my twenties when I was traveling a lot and doing tattoos. COVID slowed things down and I began focusing on painting. Now, I'm confident in who I am and what I do as an artist. And as I've developed my practice, I’ve decided I want to show under my real name.

It felt important that I put an end to the persona and pull the plug. I feel that a lot of established people in hype-based industries have missed their chance to quit. They're in their 50s and still carrying on a persona that has little to do with their current reality.

That’s real. But I can imagine people wanting to hold onto that, especially if they feel like that’s the only reason that they’re relevant. How do you let that go?

Fuck it. I wanted to jump in the cold water and see who’s actually interested in my journey. Sometimes, just like a snake, we need to shed our skin in order to continue growing. I believe as an artist, it’s my duty to leave my comfort zone to challenge not only my own perspective but also the perspective, conventions and realities of others. As an artist, you are where you are in your career because you've done the work. By deleting a social media account you don’t lose the success nor the work nor the connections you’ve made. After all, Instagram is just a platform.

Did you hold any type of memorial for Maison?

I didn't want to make it a thing and just went dancing after I deleted the account. I had a really fun time dancing by myself, feeling the weight off my shoulders and realizing that I now have space and time for other things. It felt good to let go. The account gave me a lot of independence and stability but it was a burden at the same time.

R.I.P. Maison Hefner.

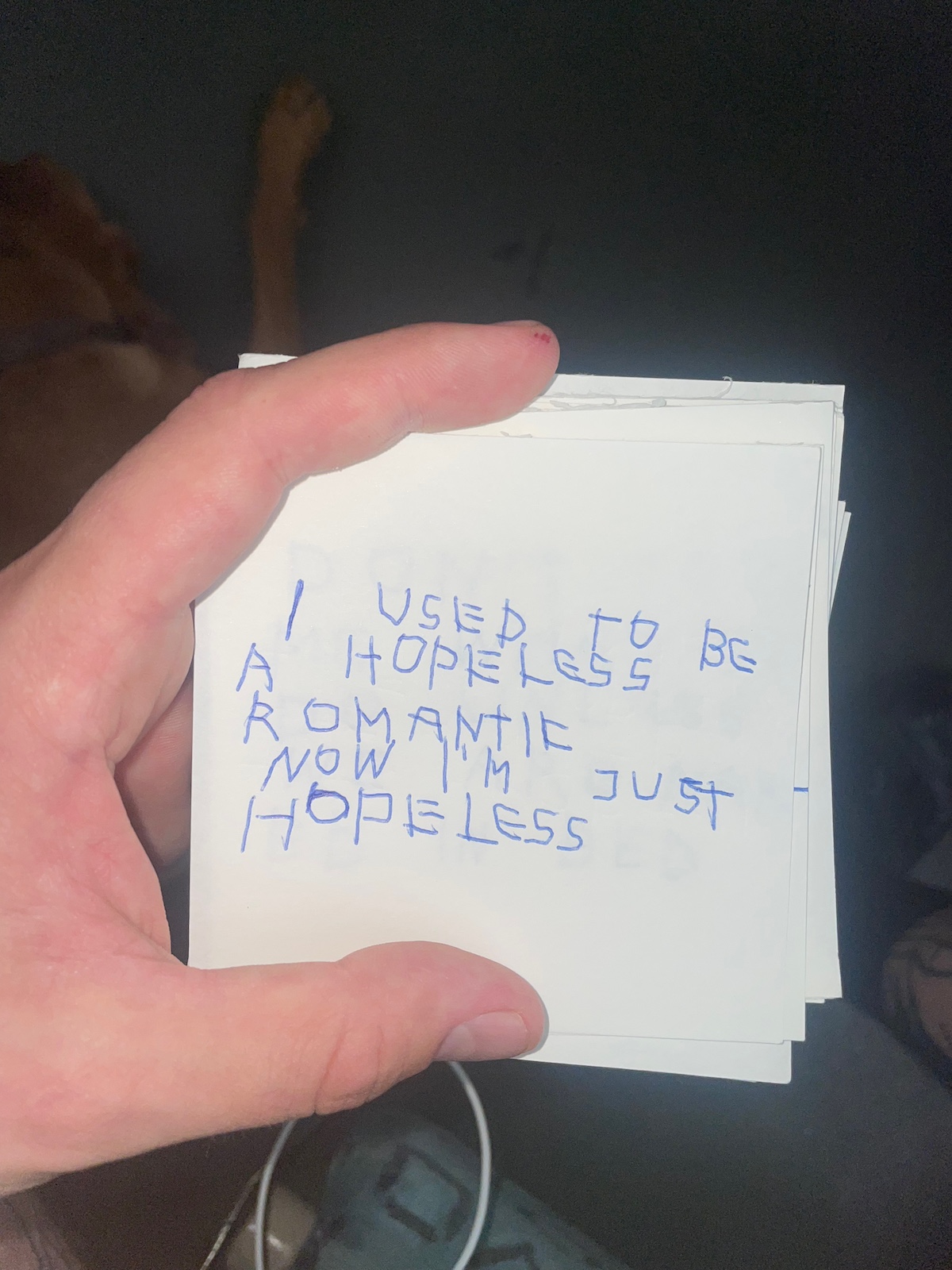

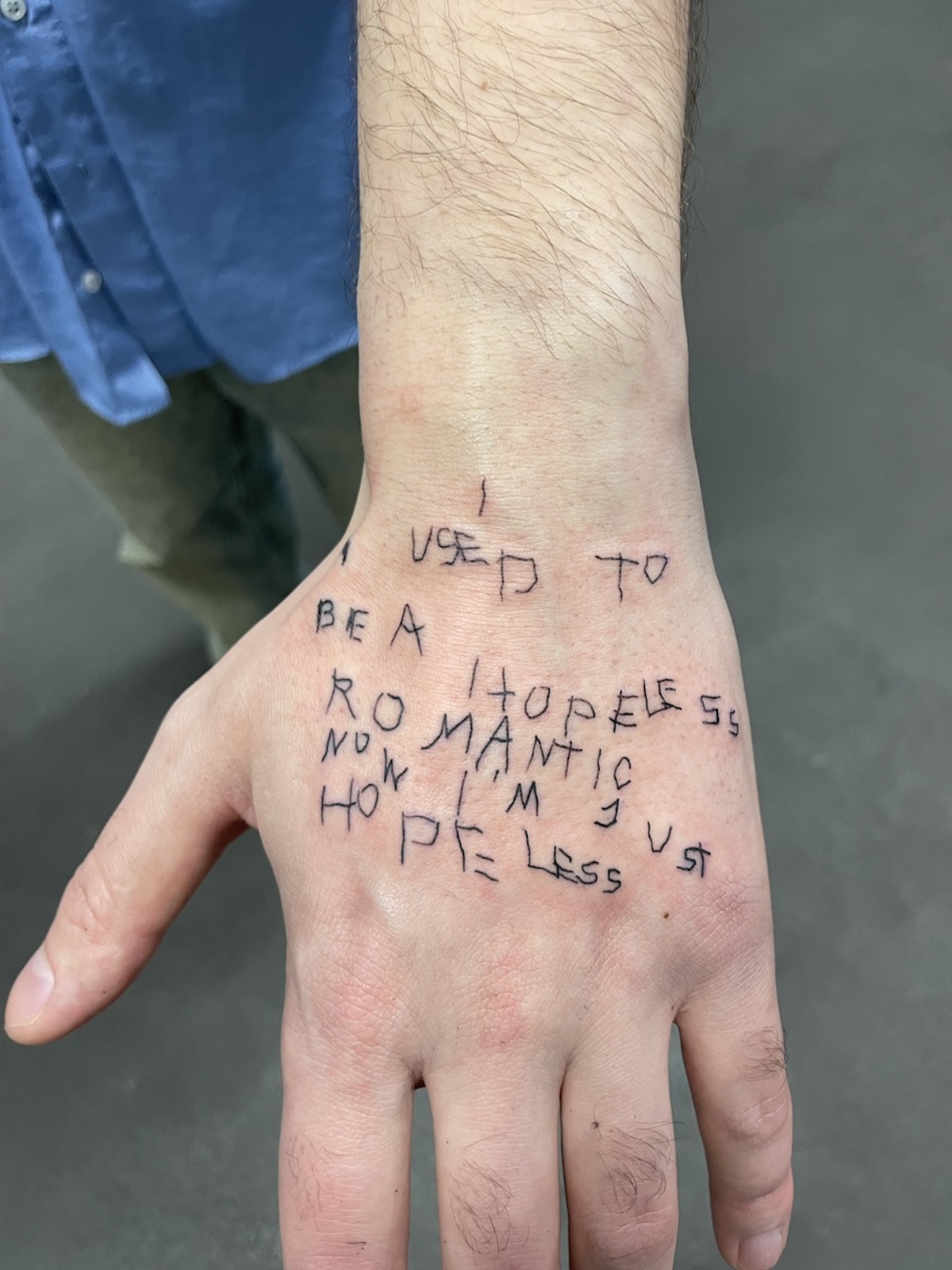

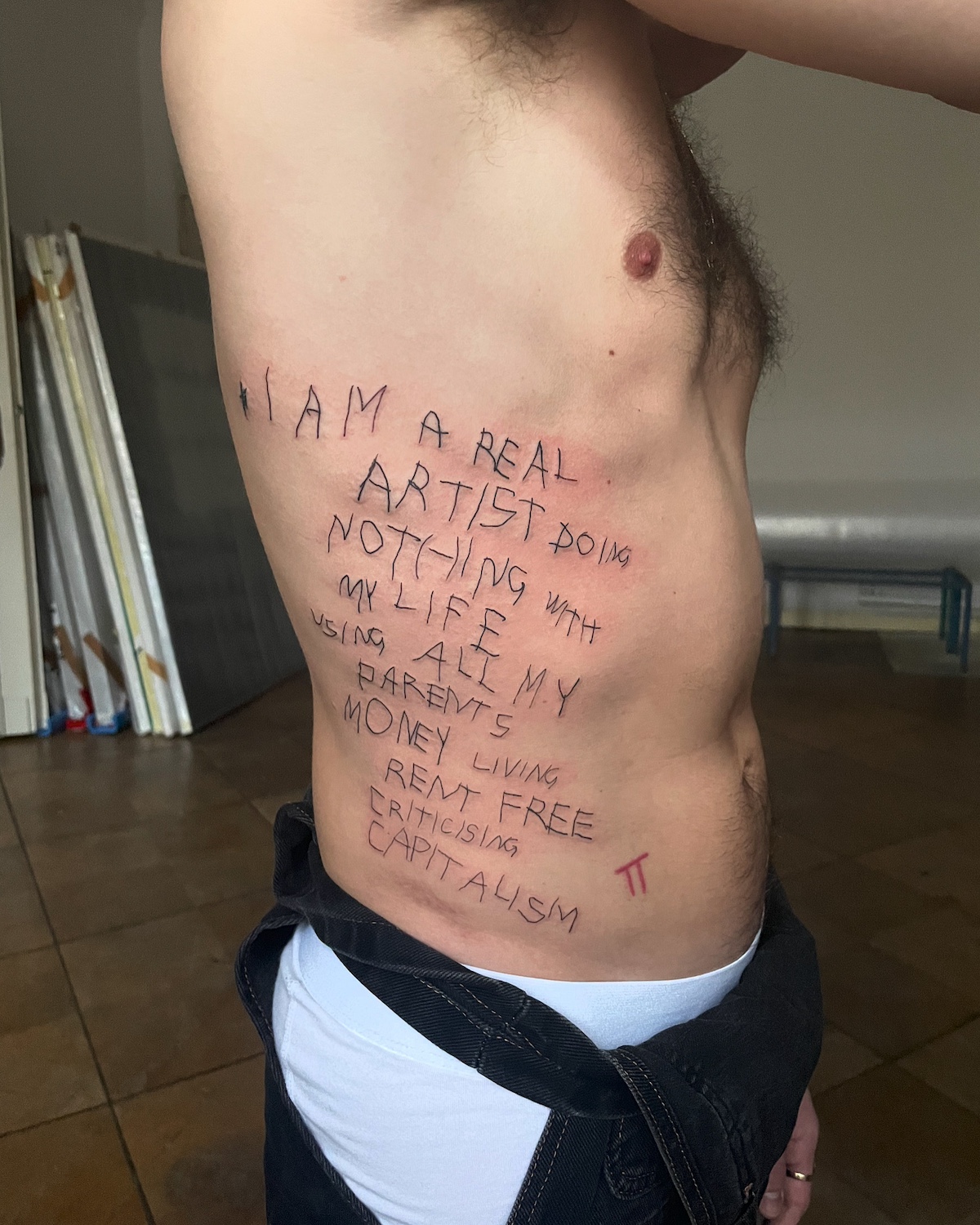

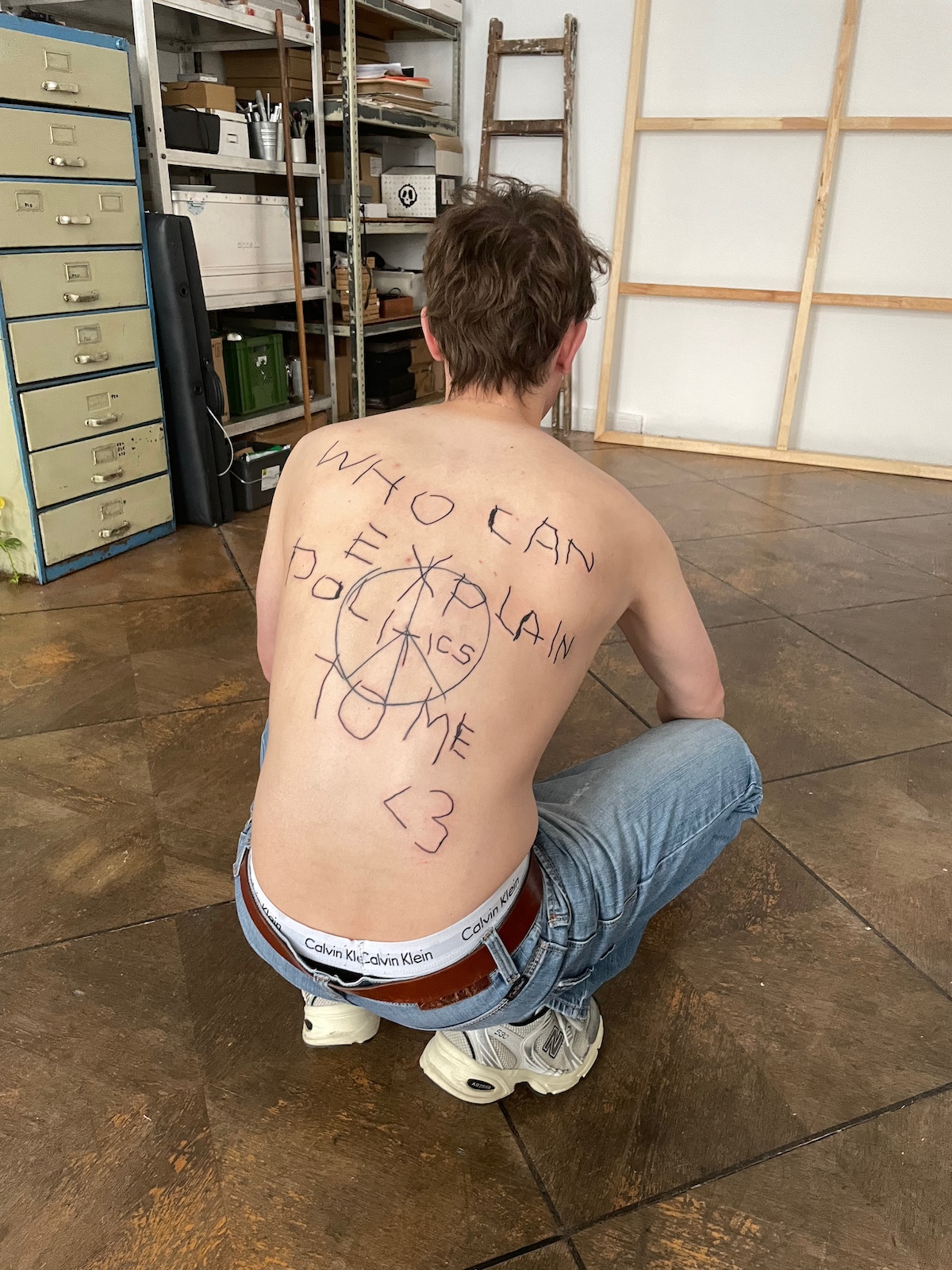

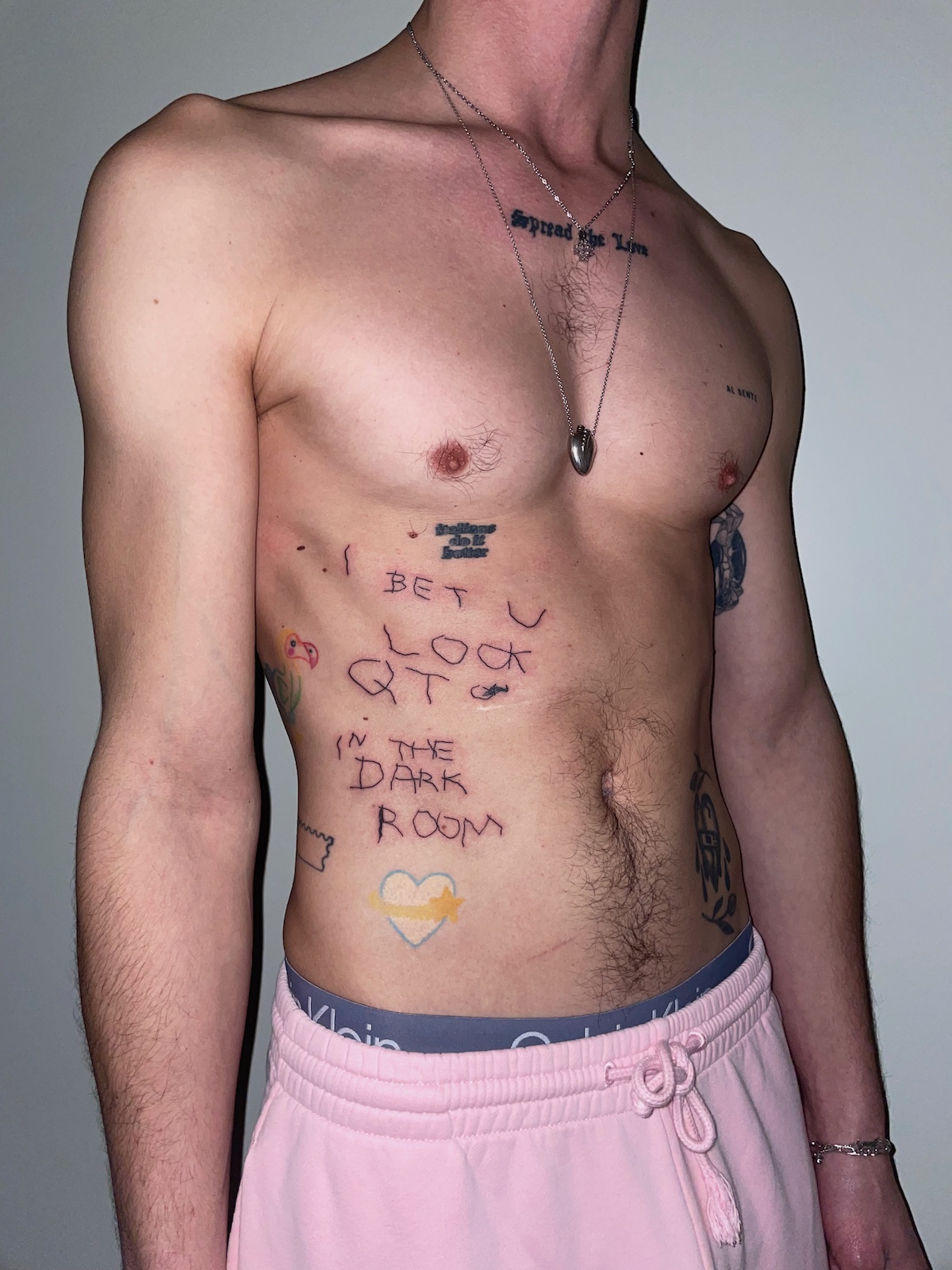

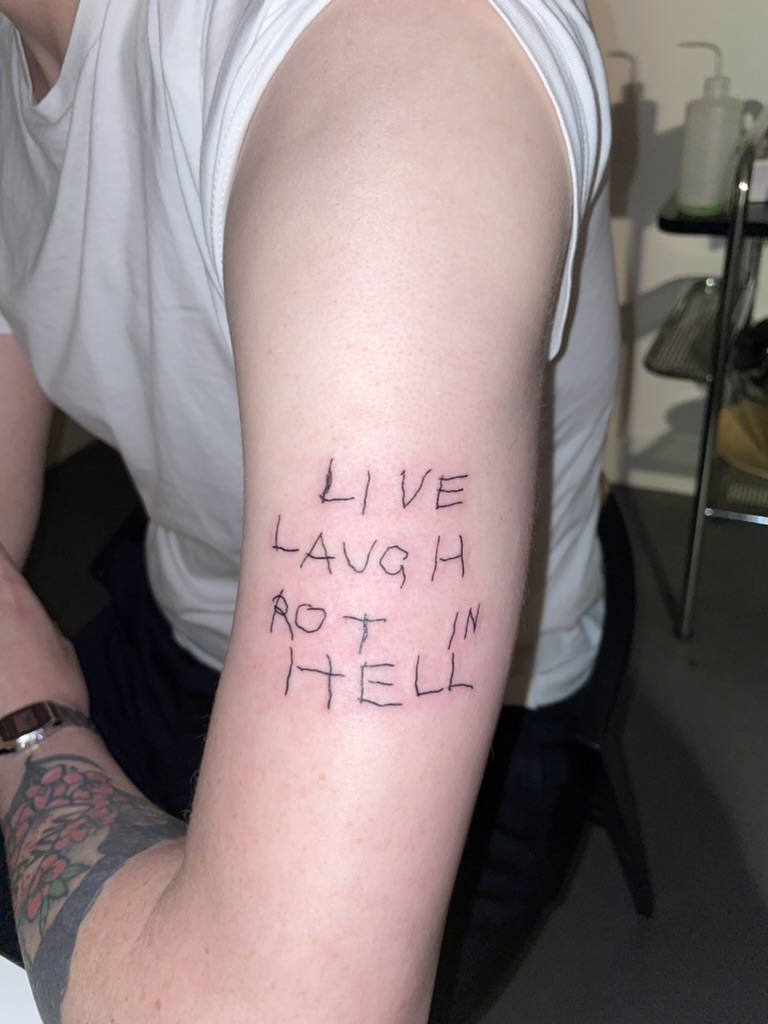

Where do the statements that you’re known for come from?

My texts are like snapshots, similar to photos. They’re memories or notes from certain moments in my life: observations from things that happened to me, things that I thought of, dreams, etc. I basically just write whenever I have time and I write until my head is empty. I have a lot of input and I need to let all of it spill out. It’s how I process things. I take out the trash.

Love that.

And I keep them all in shoe boxes, like time capsules.

That reminds me of when I go home and get to flip through the box my mom keeps all of my stuff from growing up in. I give her a hard time for it sometimes but I’m actually so glad she’s kept it all for me.

It's 100 percent like that. There's no order whatsoever. I can only roughly guess what time things are from based on the style of my handwriting or the content.

It’s interesting seeing how my handwriting has developed over the last decade. I have multiple different styles of handwriting depending on what I’m writing or how I’m feeling.

How important are these statements to your work?

Text is always the foundation of my work, but not always the visible end product. It is the basis for my ideas but from there my thoughts develop. I think of it the same as writing a script. You might start with black words on white paper but it eventually becomes a vivid moving image.

To be honest, because of Maison Hefner, I mostly know you for your tattoos. What has your art journey looked like though outside of that?

Although I went to an art school I didn’t learn to paint until after. I taught myself. And I started doing small shows with my friends, which is how I met my gallerist, André Schlechtriem. He gave me the opportunity to have my first big gallery show at Dittrich & Schlechtriem. I developed the idea for an installation called “If This Is You Who Am I”. It combined poetry and painting with sound and light and was brought to life in collaboration with Yasmina Dexter and Elias Asisi.

Do you want to talk more about the show you just finished at NAK Neuer Aachener Kunstverein, THANK GOD GOD IS DEAD?

My father died when I was only 18 years old and I felt alone trying to confront my thoughts and questions about it. Writing was a way of processing this grief through a creative channel. It helped me understand myself better as a human — a human that will also die at some point. Sooner or later. I feel like death is a subject people do not necessarily feel comfortable talking about so I wanted to create a space where one can engage with it as part of a collective experience.

The main piece incorporates three coffin-like beds and a sound piece, made again in collaboration with Yasmina Dexter. It repeats a long list of aphorisms: “THANK GOD CAPITALISM IS DEAD,” “THANK GOD SOCIAL MEDIA IS DEAD” and “THANK GOD NOTHING IS DEAD.” The audience is invited to lay in the coffins and I personally found it interesting looking at the people and just wondering what they were going through as they listened.

So are you done doing tattoos… forever?

Maybe not forever. I don’t like the word “forever,” for obvious reasons. But I think for now, I’ve done everything that I wanted to do with tattooing.

Do you have a favorite quote? One that’s not yours.

I have a cap by the artist Jenny Holzer that states, “PROTECT ME FROM WHAT I WANT.” I stole it. It doesn’t always work.