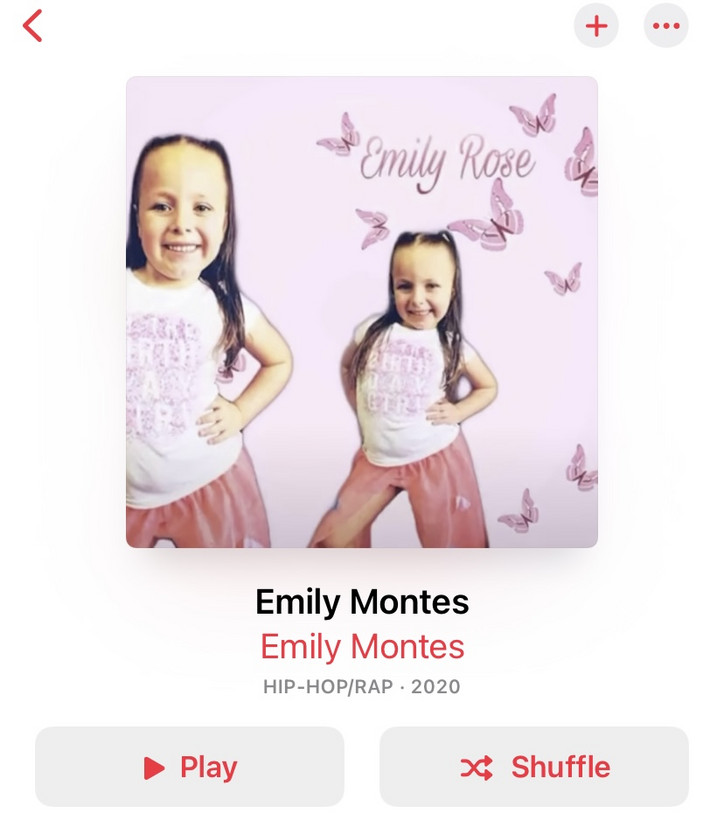

Why're People Stanning a 6-Year old?: A pseudo-analysis of Emily Rose-Montes' Music career

Her latest release “Emily Rose (Deluxe)” is an amalgam of the anxieties, anger, and overwhelming angst of the past two years under a global pandemic. It is sometimes complicated and problematic, and other times shockingly poignant and direct. The album creates a capsule through which to view our moment in time, pushing the excess of internet fandom to a boiling point.

“My name is Emily and I’m five/I like playing Roblox and going outside/I like going to school, but I’m stuck inside/this virus has me losing my mind”

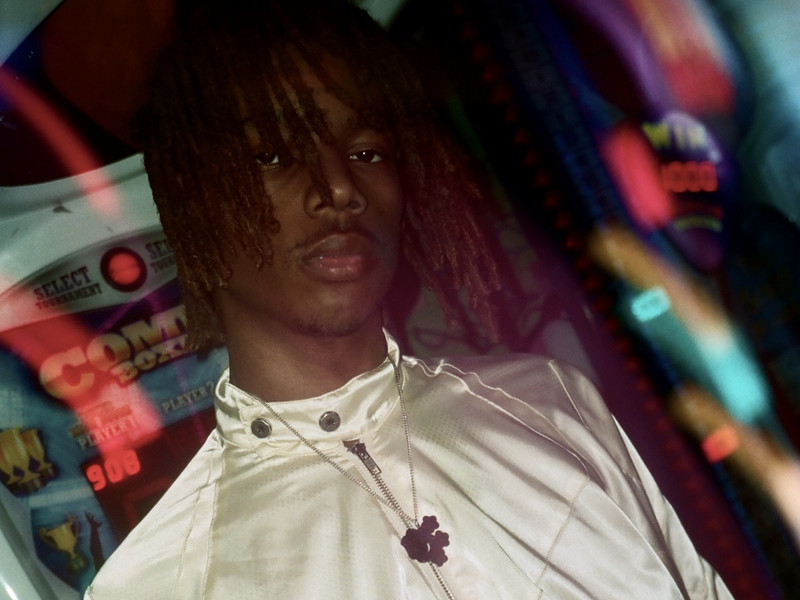

Instrumental in understanding the origins of the six-year-old sensation, is Montes’s first masterpiece. In July of 2020 Montes released her eponymous album after her first song “Emily” went viral on Tiktok, garnering 29,000 followers. The sixteen-second song (lyrics in full above) launched the then five-year-old into fame, and, subsequently, the unrelenting arms of stan culture.

As fun as it may be to jump on the stan-wagon (coming from someone who wanted to coin the Emily Rose Montes fanbase, “Thornies”), granting a six-year-old starlet celebrity status should give pause. Montes’ monumental emergence in the music scene offers a moment of reflection in how much media we make available to young people on the internet, and how quick we are to place them, in the limelight. While decreasing barriers to entry in the music industry is a worthwhile endeavor, it does not dismantle the cult of celebrity the industry is built on.

Montes’ rise to stardom is as elusive as the artist herself. The virality of Tiktok, with a surplus of new users under the pandemic, gave Montes a fanbase rife with ironic appreciation. At the same time as auto-tune, and hyper-pop glamorized adults with child-like voices, the hyper-salience of doom under a global pandemic dramatically altered our reality as we understood it. Struggling, in our personal and (suddenly increasingly more) virtual lives, to put language to ineffable feelings, fleeting thoughts, and ever-changing facts, our own neurological systems became much like that of a toddler just starting to process and interpret the world around them.

“I’m going in circles, crazy, insane/I’m losing my mind/What are the words/That I’m trying to find”

The opening of Emily Rose (Deluxe), “Intro/ Ig Ig Ig/ If Today Was The Last Day” draws on key themes in the Montes oeuvre: going outside, haters, and existentialism. But, perhaps most interestingly, is the reference to Instagram (Ig Ig Ig).

Since her rise to fame, the darlin’ diva has been banned on TikTok, and Instagram, likely to keep haters, and even fans, at bay from inflicting any harm on Montes at an impressionable age (or the violation of age requirements on social media). Moving her online presence instead to Twitter, the last bastion of the banned, Montes has beef with the platforms over her banning.

With her TikTok account garnering 29k followers following her first release and her Instagram fan account alive and well in her own account’s absence, the quickness with which we grant notoriety. The issue of celebrity has a longstanding hold on fans building mythos around and assigning meaning to people whose immediate lives are intangible. In the internet age, celebrity has become conflated with virality and made way for stan culture. The question becomes how we came to put a six-year-old in the limelight. It’s not unheard of for such young talents to find their way into show business, with stars like Michael Jackson starting as early as eight. But, as we saw with Jackson’s troubled (though extremely successful) career, to those who know nothing but the limelight, the life they are able to live is stunted, and their experiences are isolated and foreign from the everyday.

In the wake of social media’s purported “interconnectedness,” we’ve seen an opposite effect, with young people and teenagers reporting higher levels of mental illness. As a star made famous by these same platforms, can we expect Montes’ experience of fame to only be exacerbated by the cacophony of "connection" on the internet?

In the streaming era, as more artists stay independent and in control of their craft, and public image, there may be less external pressure on Montes than the supernovas of child stars burned by the music industry in the past. Can Montes achieve her desired level of success without also losing pieces of her childhood? Or are some of those pieces already lost as life in the “post-pandemic” digital age inflicts progeria on us all?

“But there is no peace/So I speak”

Though all of Montes’ songs run the gambit of everyday six-year-old gripes like playing Roblox and snacktime, to mature subject matter like love and betrayal, “Haters/BLM/Dark” is perhaps her most confounding piece.

With cognitive development starting in children at age six, we can’t expect Montes to navigate the cut-throat intricacies of internet politics. We become accountable for her. So how can we examine the culture we’ve created wherein a white six-year-old feels compelled to weigh in on police brutality? A stark reminder of the young ages at which black and brown children are first confronted with racism; how does Montes’s voice in the conversation around George Floyd’s death speak to the way children are socialized differently along racial lines?

Montes’ lyrics feel like (and likely are) a child who’s overheard a phrase among adults, and in repeating it, nearly captures its meaning, but falls just short. Leaving us, the proverbial adults, to think about the messaging we’ve made available to a six-year-old, and the platform granted her as a result. Montes’ sense of justice can only be as thoroughly articulated as it has been taught to her.

As a white six-year-old claiming the crown within a historically black genre, Montes serves as a reminder of the longstanding history of black culture as a commodity, available (and therefore disposable) to the sticky fingertips of an industry built on the visibility and notoriety of whiteness.

“Do whatever you want me to/Just remember I love you/Nicki are you mad that I dissed you? Are you mad that I rap better than you?”

In embedding herself within hip-hop, Montes’ “D.T.W/#Diss/O.T.R” calls upon the timeless tradition of industry beef. The succession of each micro-song calls first on love, and artistic devotion, before challenging Nicki Minaj, and fading into a disaffected rendition of “Old Town Road.” This progression could be intentional, aimed at conveying Montes’s appreciation of the culture of hip-hop (through the vantage point of a six-year-old, “Old Town Road” can be interpreted as hip-hop history), or entirely (and most likely) at random. The track becomes satire, forcing listeners to think critically and fill in the gaps for themselves.

Montes’s world straddles uncertainty and curiosity; optimism and near-nihilism; and an all-encompassing hunger (both for success and snacks.) Her lyrics are simple and accessible. Her sound is contemporary and catchy. As we pull apart the pieces which make Ms. Montes’ music feel whole, we project our own humanity onto her art. We search tirelessly for meaning, and in its absence, create an icon—something larger than and detached from our own experiences to fill in the gaps in our own lives.

Rather than putting the six-year-old on a pedestal (when she still needs a step stool), we ought to extend that same humanity as she explores her creativity. When sharing in her craft (by way of bumping “Be Happy/I Wanna Be Famous”— a personal favorite) we are reminded that the rules are, and should be, different for young creatives. To help Montes be happy (and famous), we can appreciate what she is doing, with constructive grace and not blind, and obsessive devotion.

By Montes’ own claim, she wants to be famous. She has learned at a young age, as many of us have, that fame is success and subsequently, is happiness. The age of social media has pushed the narrative of fame, a once intangible concept, into quantifiable followers, listeners, or likes, and we can’t blame Montes’ in her pursuit of it. Most of us find ways to maximize and leverage our own relative fame within siloes and niches to achieve individual notions of success.

So how can we alter the industry of fame to make it both less desirable to future generations, and less dangerous to those who attain and consume it? Without dismantling the power system at play in the singular idea of celebrity, we instead shift power from the hands of executives and industry giants into the not-yet-fully formed palm of a child and fail to recognize that same power we surrendered. Fame is capital, and in creating celebrities we deplete our own resources, detaching the superstars we create from theirs. We build a toxic and vicious cycle of isolation and disparity, stunting the innate human creativity Montes is demonstrative of.

In one sense, Montes builds a complex allegory for life in a post-modern, hyper-digital world, pushing listeners on a quest to make meaning from chaos, in another, she’s hungry and it’s snacktime.

“I’m hungry/I’m hungry/I’m hungry/Should I eat this?/Or should I eat that?/I’m in the house hungry/Snack time”