Wipe Your Eyes

Where are you from?

I’m originally from Tunisia, but I was born and raised in France, so I’m French-Tunisian, Tunisian-French.

Do you want to talk about the project at MoMa?

Perception is a project I did two years ago, in 2016, and actually was an artwork located inside the Cairo garbage-collector neighborhood, and the first idea when I decided to go there was to go and beautify this ugly, dirty neighborhood—but I had no idea what it was, actually. I heard about them in 2009, because Mubarak slaughtered 300,000 pigs using the H1-N1 virus and the garbage collectors used their pigs to recycle organic human waste. So, this was in the front of my mind and in 2015, I just decided to go—and I had no idea, I thought these people were kind of dirty, I thought they were living in the garbage, but they were actually living from the garbage. After a few days, my perception had changed already. You realize that the people who are bringing the garbage to the neighborhood, they come with trash, so the garbage comes from another place—and speaking with people, you realize that it’s the garbage of all of Cairo. In Cairo, they call them ‘the garbage people,’ and I kept calling them that for almost a year until we did the project, and I realized that was not their real name. The real garbage people are the ones in Cairo who produce the garbage.

It was a kind of organic project—we went, we didn’t know anyone but we connected with one guy. It’s a Christian Coptic neighborhood, so the first place that I went was the church, and it’s this crazy church that they carved into the mountain. It’s a 20,000-seat church that they built in the seventies, so when you see it you think, 'This is impossible in this place'—it’s inside Garbage City. It’s amazing, when you see it, it blows you away.

So, the people live off the garbage?

Right, so people bring glass, paper, plastic, and each family specializes in one thing. Some people, they collect everything, some people they just collect plastic, some people take care of another specific area. So, each one is allocated one area.

What do they do with it all?

They resell it and recycle it. They recycle more than 80% of what they collect—it’s the most powerful recycling system in the world.

And they just did it because they’re poor?

That’s what it was in the beginning, yes—it started like 60 years ago. There’s 70,000 people living in this neighborhood working together now.

So, you went in and painted the roofs?

No, it’s an anamorphic piece on the sides of the buildings that you have to go on top of the mountain to see, so it goes over 52 facades and covers 258 meters, something like that. But they’re not poor people, that’s the thing. They’re not poor. Some of them are super rich, that’s your perception—because they work with garbage you already think that they’re poor. There’s a disgust.

So, they do well?

Some of them, they do super well. Some guys have a jacuzzi in the house, huge American kitchen, a flatscreen tv—they’re living the life! And they tell you, 'This is our income, we work from this, we make our money off of this.'

It’s business.

It is business, and you know, when they’re done with work and change, they’re like regular people. And they’re working from something that no one really wants. And some of them have contracts with big brands—some families have contracts with L’Oreal, brands like that—because they collect their shampoo bottles and then sell them back to them.

Above: 'Perception' and the artist surveying his work.

So, what drew you to this?

I don’t know—the first idea was to challenge myself. The first thing was an artistic challenge. Then I said, 'I’m going to go there, I’m going to beautify this place.' Then I realized, I don’t need to beautify anything—the place is beautiful by itself. For me, it was one of the most beautiful places I’ve seen. It smells bad, and it’s kind of dirty from the garbage, but there’s beauty despite that.

It’s kind of a beautiful concept, as well.

It’s the idea—the way people welcomed us. It’s kind of a segregated place, nobody will go there. The cops won’t go there, the government won’t go there. So, we spent a year going back and forth, and we spent one month to make the project, and then when you leave you have a kind of family there—when you leave you’re a part of the neighborhood. We’re going back on the tenth of November for a wedding there. It was a really powerful experience—beyond the artistic challenge, and everything that surrounds that, it’s what we lived through with them, and that, for me, is the most important thing. That’s why I took the time to write this book. It’s not just pictures of poor people—I made an artistic choice with the guy filming. I told him not to take pictures of people working in the garbage, because instantly you will have the wrong image. When you see someone with their hands in garbage, you think, 'This guy is looking for his food in there,' when actually he’s just working—the same way you’re working as a journalist, or a guy works in a bank.

So, the book is all about this project?

The book is about this whole journey, how I started this whole adventure from an idea. These people are a pretext to talk about the subject of perception, there are so many people who misjudge because of a stereotype, and for me, this is a way to push people to think about their perceptions of others. As an artist, it was important for me to question that—what is it to be a minority? To be misjudged? Marginalized? Segregated? Because of nothing, actually. They’re doing something really useful.

So, the work itself is Arabic script, is that correct?

Yes.

What does it say?

I work with Arabic calligraphy, so all my work uses words. I write messages, so every time I go to a place, I try to write something that is relevant to the place where I’m creating the artwork. So, in Egypt I used a quote from a Coptic bishop from the 4th century, St. Athanasius of Alexandria. And using this Coptic bishop was a way of convincing the neighborhood—and to convince the neighborhood I needed to convince one guy, and that was the priest. So, when the priest said, 'Okay, you can do it,' it opened the door to the entire neighborhood. People said, 'If the priest said ok, then go ahead, paint on our houses.' So, St. Athanasius said, 'Whoever wants to see the sunlight clearly needs to wipe his eyes first.' That’s the quote.

So, the cover of the book mimics the piece?

Yes, I handpainted over 500 book covers to recreate the piece from Egypt. We used recycled paper from the neighborhood to make the book that we bought from them. The paint that we used was blacklight-reactive, so at the end of the project we lit up the whole neighborhood with a blacklight—all the garbage kind of disappeared, and it was just the message coming out. And we have a similar piece in the book that will glow under a blacklight, as well.

Was it difficult to get the priest in the neighborhood to agree?

The priest is a kind of celebrity, he’s like the Justin Beiber of Christianity. He’s a super star. When I saw him the first time, I thought it was a fight—people were jumping to get closer, it was crazy. He accepted to meet me because I’m an artist, and I met him twice. He was actually super open. It’s interesting to see how one guy can have so much influence over 70,000 people. And they welcomed us—we’re not Christian—but they welcomed me like I was their brother. It was amazing.

For me, this whole thing was breaking this kind of propaganda we see right now, that there’s always a conflict between Christians and Muslims, conflict between Muslims and Jews—and here, there was none of that, not at all. The funny thing was there was this one Christian guy who asked us to repaint a mosque—5% of the neighborhood was Muslim and there’s this tiny little mosque—so, the guy was like, 'When you finish, I want to you to repaint the mosque,' because his house was touching the mosque, and because his door was blue, he asked us to paint the mosque in blue to match. So, now when you’re in that part of the neighborhood, you see this blue mosque, and it was asked by a Christian guy. We did it with leftover paint from the project.

What shade of blue?

Like a royal blue.

And he was just being neighborly?

He just wanted the mosque to match his door. But it was interesting to interact with these people and see how they treated things like education, too: one guy, he couldn’t read, but his son was getting a degree in business management. So, now they can take their business to another level. And that’s what's interesting. And there was Wifi everywhere in the neighborhood—it was better than New York in that way. It’s an incredible place.

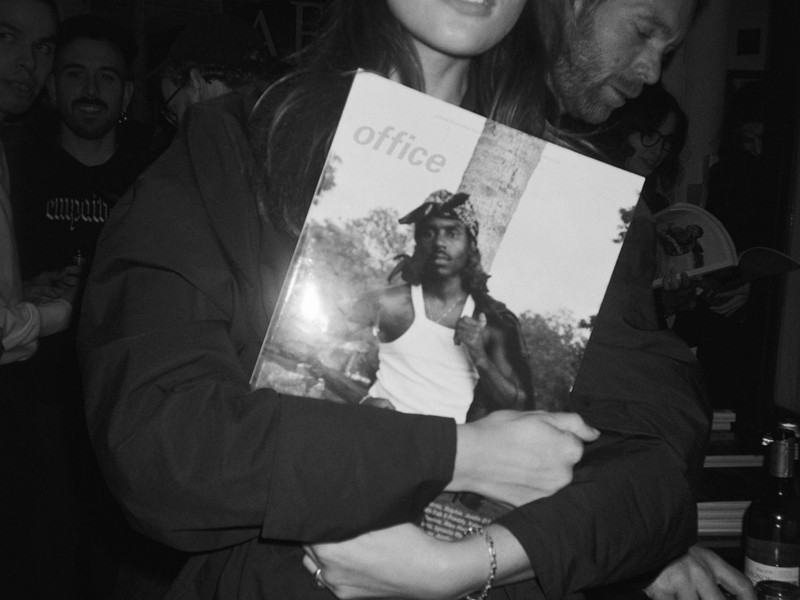

Above: The artist recreating the work across the covers of his book, and a local boy viewing 'Perception.'

Interested in a book? Visit the launch page here.