Wish You Were Here

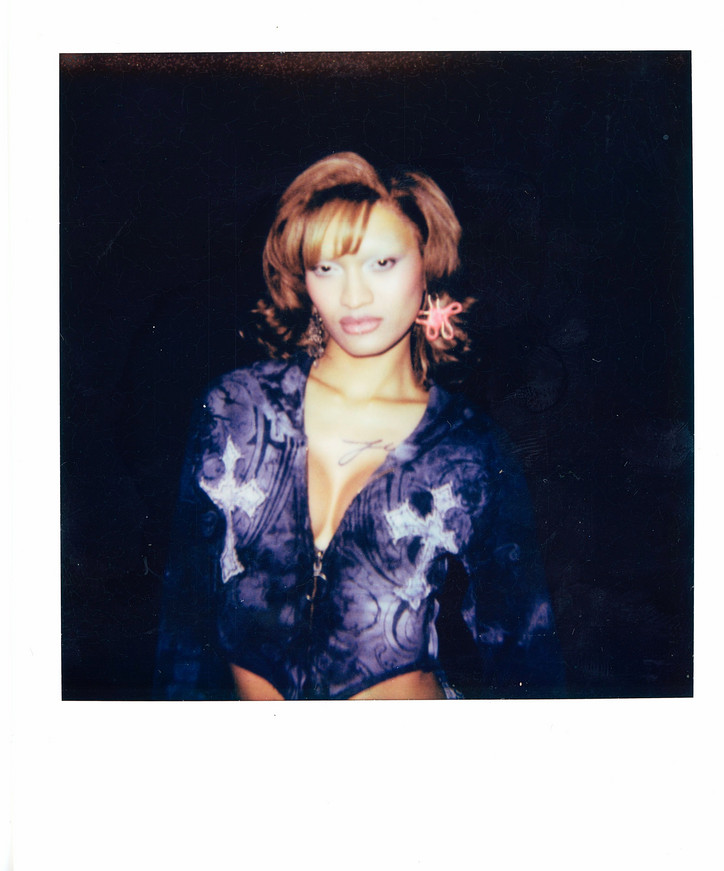

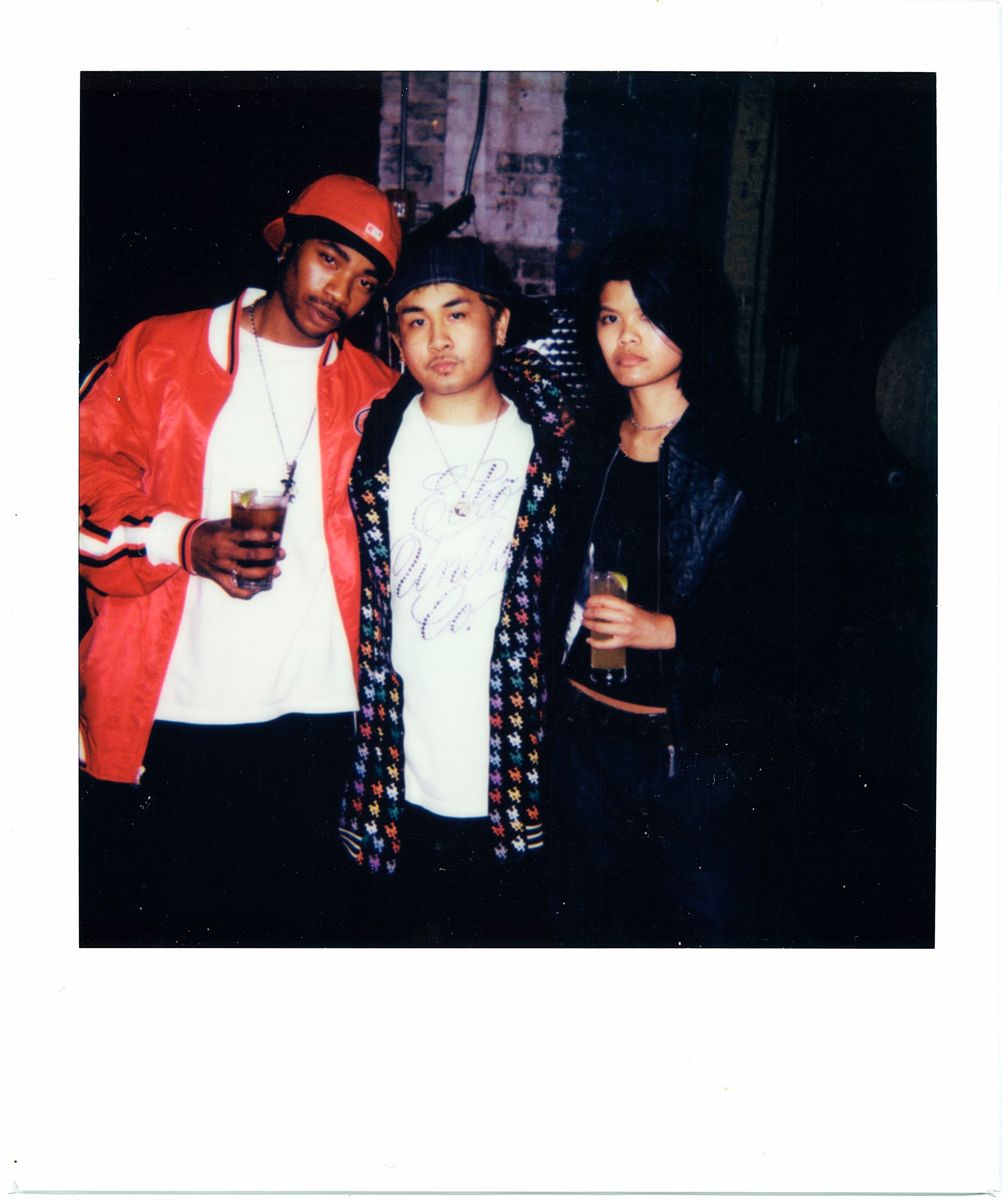

I have many friends and loved ones in or from Miami, and part of my pitch to office was that I wanted to write about my experience hanging out with the filmmakers, going to their parties and riding with 18 young people while smoking weed and dancing in the stretch pink Hummer that transported us to the main screening. I’m doing it now. When we poured out of the hotboxed outrageousness of our ride, instead of impressing the people we thought would be standing outside, we instead bewildered some security cards. Everyone was already in the theater. I brought in a box of calamari from Garcia’s, and some fried chicken.

On the day of a different screening, my Hummer companions—now joined by what felt like a gaggle of foreign correspondents—were driven in a deluxe black minibus to Bayside Marketplace, to be loaded onto three boats operated by Thriller Miami Speedboat Adventures. Each boat was brightly painted with the words “Thriller Miami”. These murderously fast cigarette boats chased each other around the ocean, jumped over wakes, and delivered on their promise, which was to thrill. Our driver was named Brian and looked exactly how someone who did his job should. Brian was bursting with charisma, ravenous for speed, and told us he enjoyed woodworking. Music played very loudly, most of it in Spanish and terribly danceable. Despite the intense wind people managed to use lighters, and as we disembarked, Brian thanked us for leaving behind that "sweet smell".

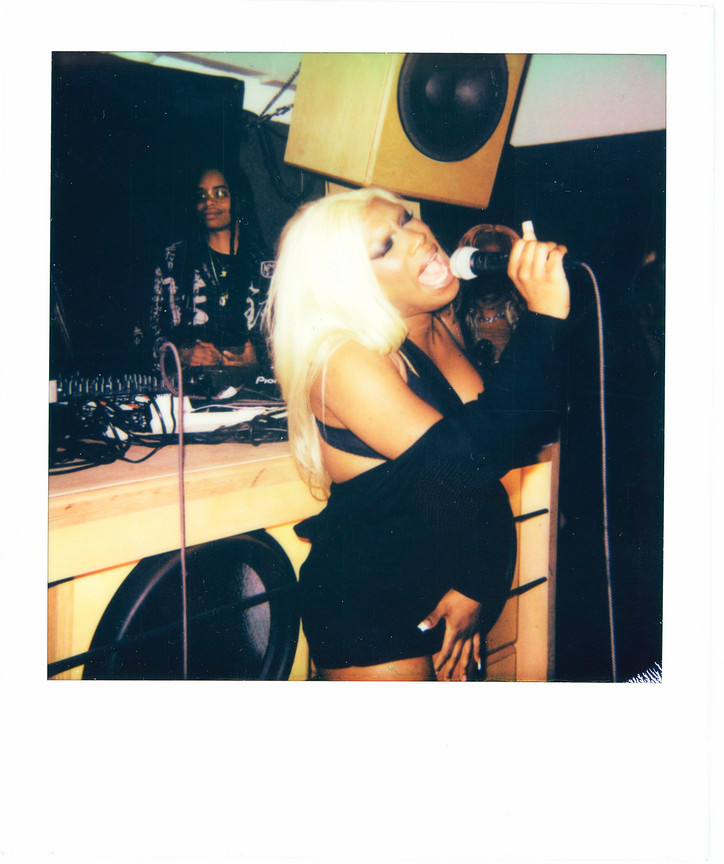

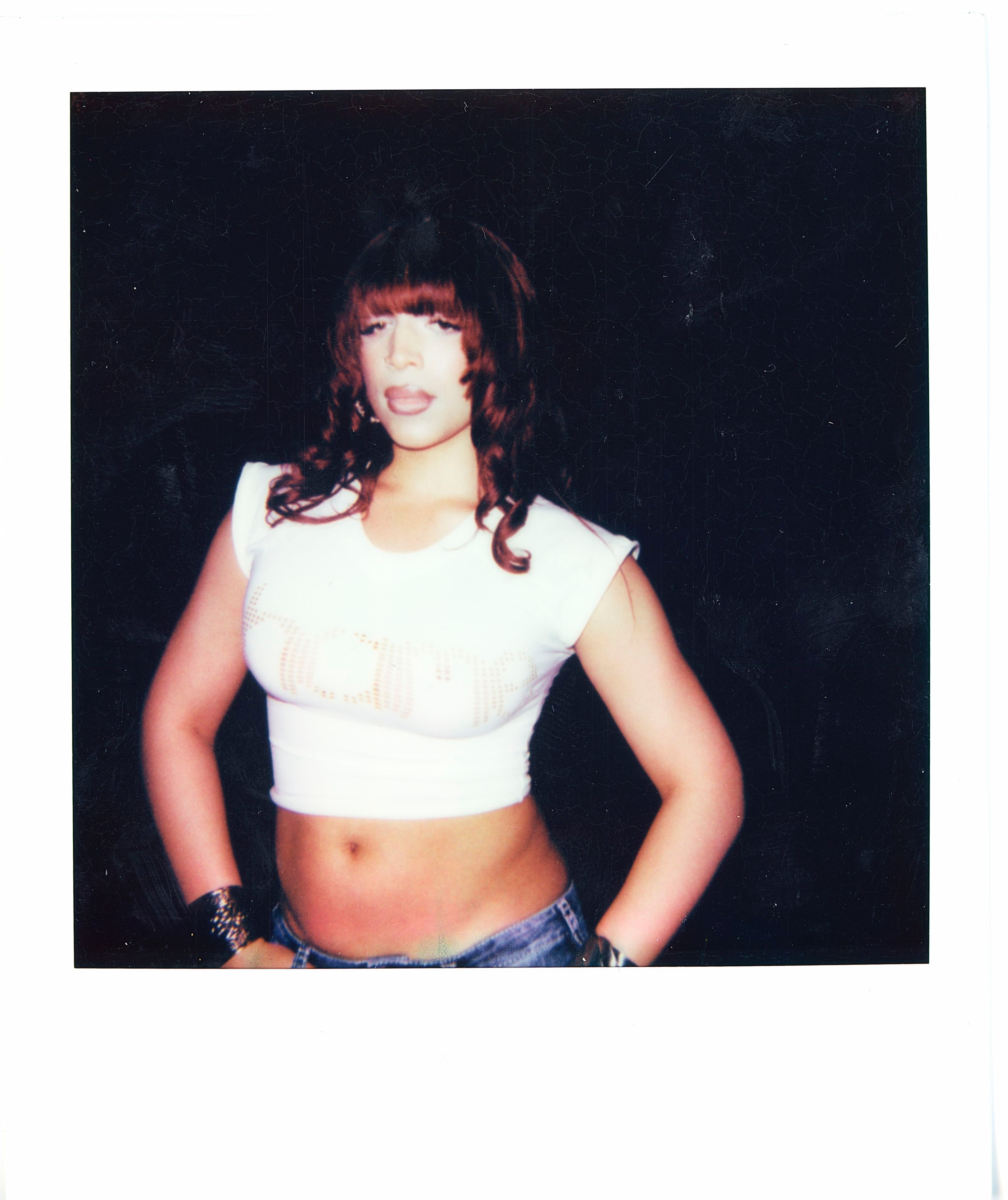

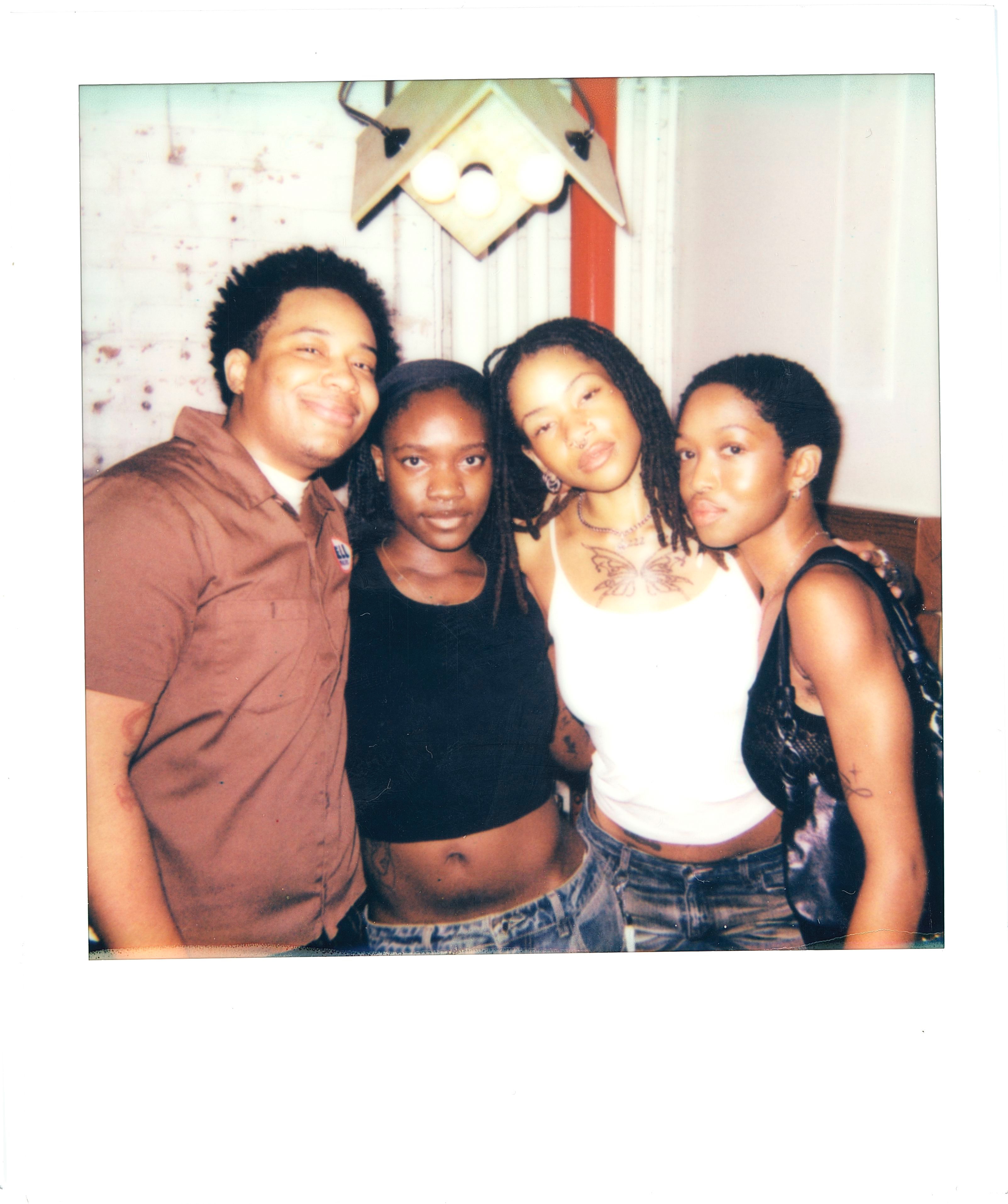

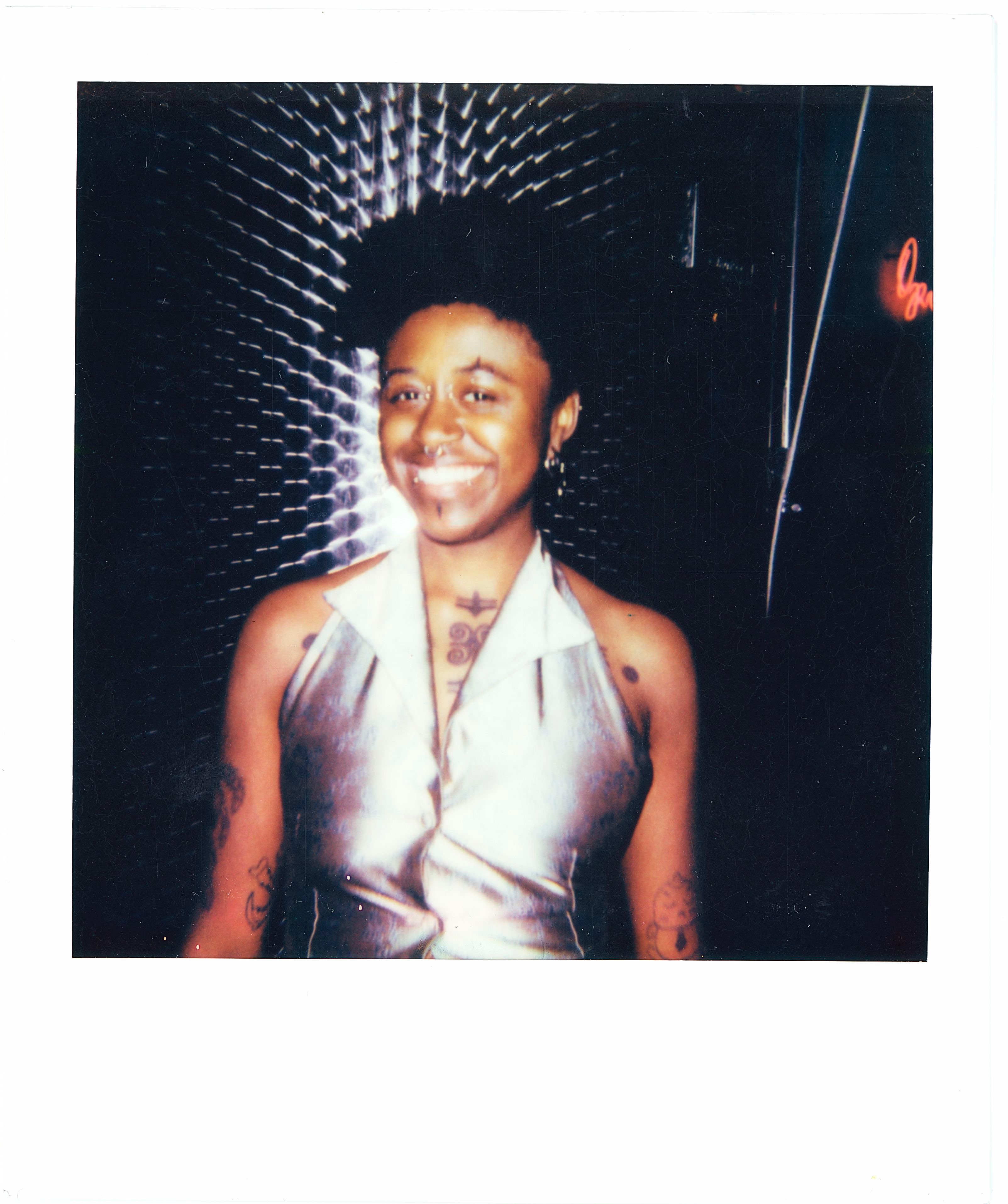

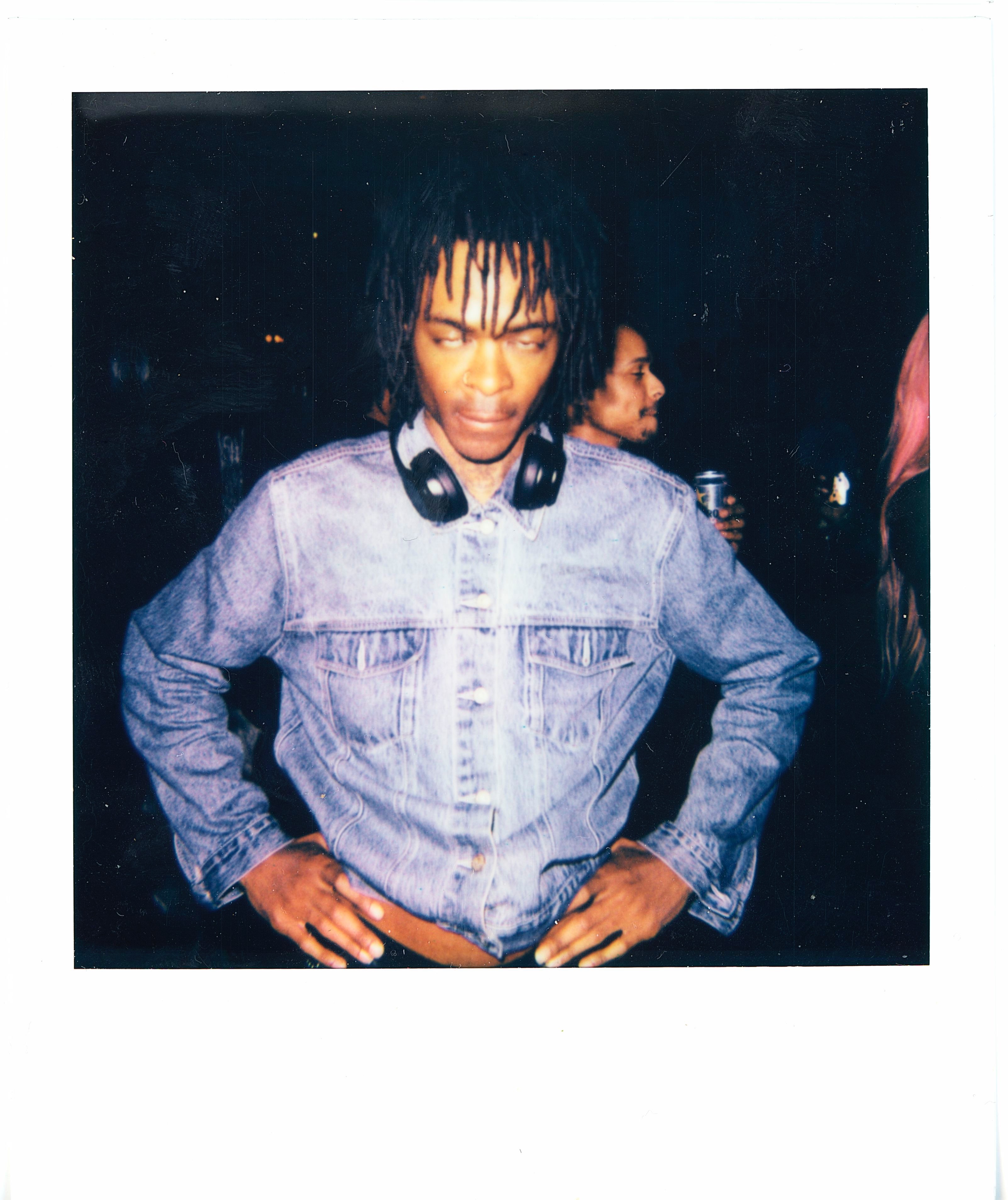

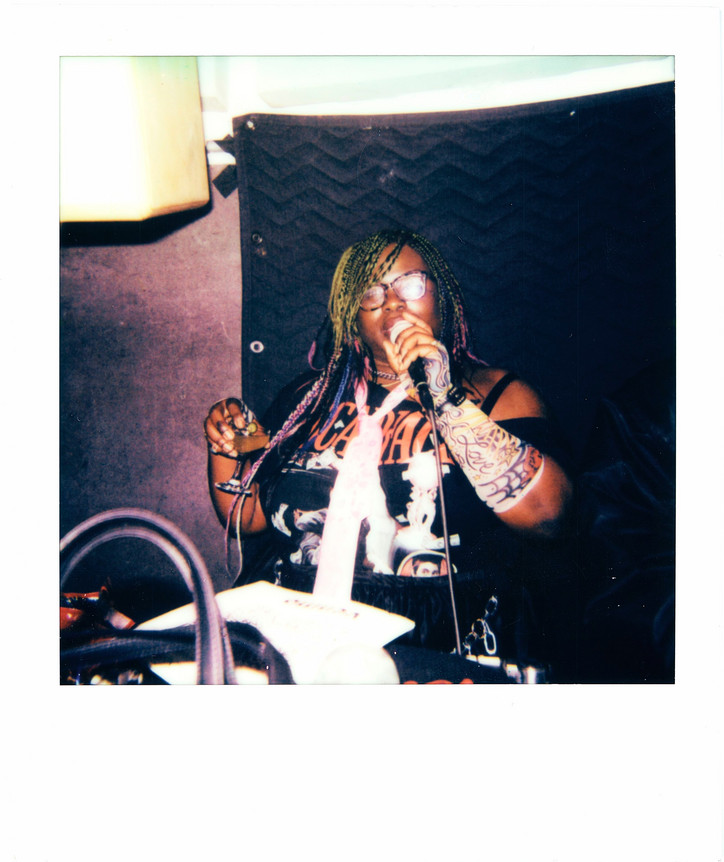

Just as with the Hummer, the Thriller was a first for me. It was extraordinarily fun. It felt like artists helping each other relax during what could potentially be a nerve-wracking time. These photographs of my Hummer and Thriller experiences show what I cannot tell. “Show don’t tell” is a maxim in filmmaking.

A major part of Borscht’s mission is the documentation of a "real Miami". Funding is almost entirely allocated for local filmmakers, specifically people of color, members of the LGBTQ community and first generation Americans (children of immigrants). Miami is one of the most overly depicted cities in film and television yet has some the highest disparities in wealth per capita in the United States. The Miami of Scarface and CSI is not the Miami I've seen. It’s a city in perpetual flux, forever craning its head above the water of hyper-gentrification. But it’s also a city with chill beaches and local spots and dead malls, leant to the arts community by MANA real estate properties as artist studios that serve as dance clubs. It’s a city that supports local artists and the arts generally in a way that seems rare. The films made by these Miamians (which I will discuss soon), are not stories about running drugs, gunfights and pastel eroto-topias. They are personal, geographically realist, funny and poignant.

Part of what made many of these films so beautiful was the sincere motivation to tell a true story about a mostly fictionalized city and it’s often miscast citizens. The morning after my late arrival, I ate breakfast and showed up late to the first screening at, bizarrely to me, a Scottish FreeMason temple. When we arrived all the seats were taken, so I sat on the floor and pulled out a small notebook and pen I’d bought to take notes. Scribbling on the paper in the dark, I felt like a sort of "performative journalist". The highlight of the night was a film called JOKER GANG, by Billy Linker and Ben Carey. This film is about a man who tattooed his face to look like the Joker from Batman. Although he claims (inexplicably) to have undergone this mutilation to ameliorate the intense sadness he felt when his ex-girlfriend aborted their baby, it quickly becomes clear that Joker305 is just another person trapped in the obsessive delusion that Instagram fame equals money.

The Joker is obviously unwell. He remains steadfast in the wake of unrelenting harassment during his live Instagram videos, which are prominently featured in the film. An Instagram Batman is shown arriving at the Joker’s home to fight him, only to be sucker-punched before he’s able to exit his Acura. The Joker meets a stripper who also wants to be famous on Instagram. They do a photo shoot. He stalks her. He posts a video toting an AK-47 while wearing only diapers. The narrative slow dives into the Joker’s broken heart. Towards the end, he appears to try taking his life using antibiotics. His live video ‘haters’ goad him on. He stops recording.

The films screened on the following day were all done by members of Bisque Corp, a younger iteration of Borscht that sprung from their fellowship program, coordinated by Trevor Bazile, a filmmaker and saxophonist whose own short film, Art Blakey Self Portrait, was good, eliciting laughs in tears in just a minute. Before the films were screened, Lucas Leyvas, one of Borscht’s founders, explained that when the non-profit was established in 2010, they vowed to never work with anyone over thirty. Since most of the original gang are now in their thirties, Bisque Corp was created to prevent the scene from becoming geriatric.

Most of Bisque’s members are fellows or interns. They in some way help Borscht, who in return helps them back. There were a few noticeable differences in the films made by those in their twenties and those in their thirties. Besides the preponderance of social media images and techniques seen in the Bisque Corp films—things like emojis, memes, and entire shorts that depict only what transpires on a laptop screen—there was an unusual number of films shot using GoPro cameras.

I wondered what this meant ontologically for those born in the nineties who’ve never known a world undocumented, clicked, liked and shared. The GoPro as a camera technique seemed to imply one of two things. It could either be solipsistic, in that nothing exists for these filmmakers unless it can be verified by their field of vision, or it could be wholly self-negating as if these same people can only qualify their existence by verifying they live in the landscape they capture.

Here are some working cuts from the Bisque screening that stood out.

The Five-Year-Old Teacher (Kiki's Class) by Luis Fernando Medellin. This very short film simply depicts a young girl teaching stuffed animals "sight words", or prepositions. The girl is adorable as are the dolls are seen absorbing knowledge in close-ups. Out of context, it could look like an excerpt from Sesame Street. There is no subtextual irony, or really anything out of the ordinary, except its own unordinariness. I enjoyed the confusion.

In A Lesson About Love, Harley Shaw documents seven minutes inside of a spy store, which she films wearing hidden cameras on her body. It’s a good one-liner of a film, and one-liners are important. The protagonist is never seen, only seen being seen. On her first visit, she asks the salesperson mundane questions while capturing him unawares on tape. On her second visit, she gets busted by a different guy at the counter who threatens to press charges against her. The rest of the film takes place on iMessage, where Shaw tries to talk her way out of being charged.

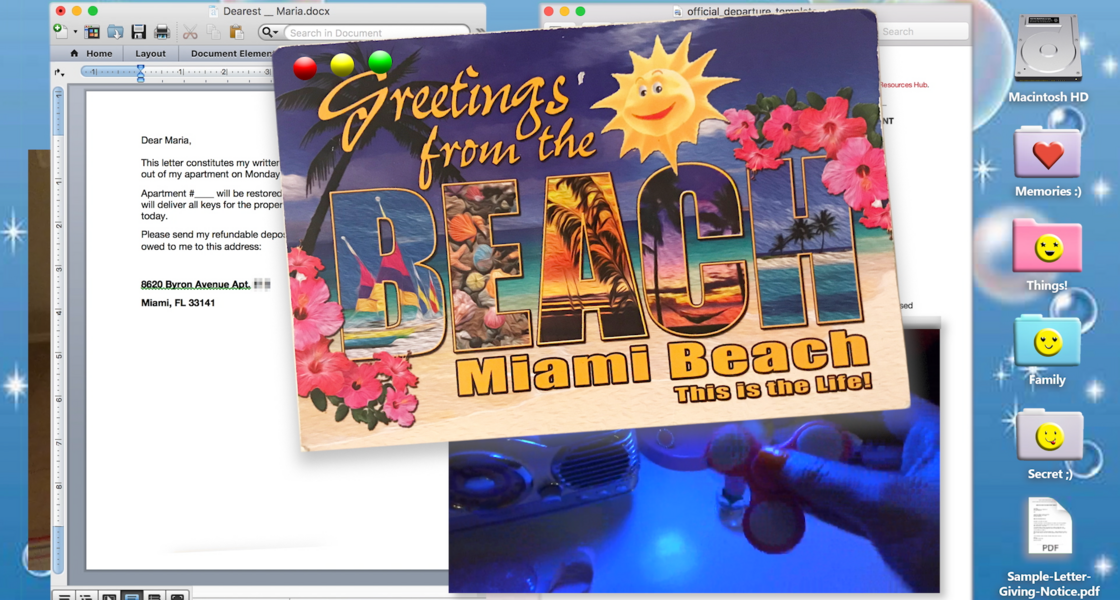

Dear Maria, Lena Redford, 2019

In Dear Maria, Lena Redford manages to successfully convey sadness, comedy, appealing visuals and some heartbreak in under four minutes. Tragedy and comedy are best friends in good art, and Redford is at home with both. Almost the entire film shows what’s transpiring on Redford’s laptop screen. There are other shots of her lazily preparing to move out of her apartment recorded with either an iPhone or GoPro. Redford is writing a letter to her landlady, Maria, using a template, to inform her that she’ll be decamping from Los Angeles for Miami. She is giving notice. While she talks aloud, she modifies the text, until she’s writing Maria a personal letter describing what’s been going on with her, and why she’s moving to Florida. Redford speaks in a satisfyingly blase voice about her life. Redford tells Maria out loud that she’ll be “moving out tomorrow, which is cool, cause that is soon.”

Her one-sided conversation with Maria is sweet, and also reads like Redford is trying to encourage herself about how easily she can clean up the apartment and move out. She tells Maria she’s moving to Miami because that’s where her brother lives, and not Scottsdale, where her father lives, apparently so he can receive treatment for what seems to be a serious illness that’s never revealed.

Redford is very funny, her voice is funny, what she documents and how she does it is funny. The offhand remarks about her father add a nice undertone of sadness that doesn’t feel sappy, just real. In one brief shot, she’s shown putting a fidget spinner into her pocket, and this somehow feels important.

Hoy!, Pedro Bello, 2019

Hoy! is a very confusing film in a way that feels positive. Bello, playing himself, appears at the beginning as a man who keeps falling up and getting down. The style of the film is obscure videogamesque. Bello is harassed and encouraged by a strange purple man who looks like a genie and calls him both a jerk and a friend. At some point, Bello is ordered by a second-rate X-men/Transformers type character to take part in a production of King Arthur, where he’s meant to play a tree. As in Redford’s film, a lot of things are described as ‘cool’, even when they aren’t. Bello’s character is cute, has Band-Aids on his face, and seems both chill and confused. I can’t say I understood the story I watched, or that there even was one, but Bello has a great slapstick style, and many times while watching his film I laughed, which is positive.

It was the night we poured our pink Hummer spectacle onto the empty red carpet of the Adrienne Arsht Centre that I saw the films I liked most. Happily, to me, there is a store in Miami called Sib-Bling Jewellers. I wanted to mention this but had no reason until I saw Emergency Action Plan by Dylan Redford, brother to Lena.

Emergency Action Plan, Dylan Redford, 2019

Emergency Action Plan is bookended by two segments where Redford is being interviewed about childhood memories. In the first, he’s in Grade 5 and has been chosen to by his principal to be a victim in a school-wide earthquake drill. Redford has an unrequited crush on a girl in his class named MacKenzie. He describes how a bell goes off at 11 A.M., at which point he is taken to the library, covered in fake blood, and told that he’s been crushed to death by a fallen bookcase. He tells his interviewer that he fantasized about his death would garner MacKenzie’s attention. In the second childhood flashback, Redford describes a fantasy where, after having been killed by the bookshelf, he walks back to class to find a note on his desk from MacKenzie which reads, “I’m glad you’re alive”.

After reminiscing about MacKenzie, Redford, sitting at a table in an unremarkable shirt is asked about an email he received on September 10, 2017. He describes having gotten an email at work asking him to prepare an Emergency Action Plan for an Active Shooter scenario. The young boy killed by a bookshelf is now spurred by memory to prepare as best as he can to be shot in his office, because as says, “I have zero confidence I would survive an active shooter attack. If anything I would be the first person nailed.”

Redford is a very good actor (appearing in other films), and while watching his film, I realized I was witnessing for the first time the creative aftermath born by a generation of kids drilled daily to prepare for a bloodbath. Redford’s character is very enthusiastic about taking up his company’s directive to prepare for violence. He watches ‘hundreds’ of active shooter drill videos on YouTube. He googles “what kind of guns do active shooters use”, then purchases those guns (for self-defense). He buys striking dummies, bulletproof vests, and hidden cameras. Through his enthusiastic effort to remain safe and do what his company asks of him, Redford unwittingly becomes flagged as a potential active shooter due to his search and purchase history. In the end, Redford envisions himself shot to death by a SWAT team, who’ve now thwarted one active shooter attack by eliminating an overly enthusiastic, highly neurotic office employee. Emergency Action Plan is very funny, but is also an intelligent satirical analysis of American gun frenzy and perpetual surveillance.

I Cannot State my Position, Kayla Delacerda, 2019

I Cannot State My Position is a surgical gem of a film that autopsies mansplaining. Delacerda’s film is atypical in that it’s shot on a Sony HandyCam, and consists of an irritating young man explaining to Delacerda why she cannot and will not be able to make good art using a Sony HandyCam. Interspersed between beautiful low-fi shots of sunsets and approaching trains, an obnoxious, teenaged seeming white boy interrupts Delacerda constantly, telling her that what she’s recording just can’t be art. His unbearable admonitions are the soundtrack to mournful images of birds and sky. While being discouraged unrelentingly, Delacerda attempts to defend herself, only to be told by her friend, with a finger pointed, to "let me finish my thought". His thoughts about what Delacerda can’t do, never finish. “Ok, Kayla, it’s not like 1929—anybody can record anything, anything can be recorded, Twitter exists....” Sage words about Twitter (?).

Delacerda’s friend insists that to make art, she needs to capture the moment. She says she is. He says she’s not doing it the right way. His issue seems to be that her equipment is too ‘basic’, which she explains is all she can afford. That it’s a white boy telling her she’s ‘capturing the moment’ with the wrong equipment is telling. I felt a palpable sense of discomfort listening to and watching Delacerda be talked down to. Ironically, her ‘advisor’ asks her to turn the camera away from him, as it makes him uncomfortable. Towards the end, he says that he better not end up being in the video. In making that conversation her film, Delacerda eviscerates her mansplainer, and captures the moment perfectly, creating a beautiful piece of art that is simple (not because the camera is simple) in its exposition of what women have to put up with if they want to talk to men about their artwork.

Why Did You Look Back, Cristine Brache, 2019

Why Did You Look Back is, like many other films I saw, autobiographical. This is normal. Brache’s film felt different, in that it also felt very film-ic (in part because it was shot on film), in a way that implied the beginning of a larger story, while still managing to function perfectly as a short film. From the striking title card to the soundtrack and color and cinematography, Brache’s film felt confident from frame to frame. As you hope for with good writing, there wasn’t a shot or line that felt expendable. All of the cast are actors.

In the first shot, a sad teenage girl exits her home to the sound of dramatic Latin music that felt reminiscent of a showdown scene from a Western film. Once she gets into her aunt’s car, the high drama subsides, and melancholy sets in. The film tells the story of a young girl named Soledad, who’s appropriately bummed out, and the attempts by her maternal family members to help her feel better by way of a Santeria ritual. In the car with her aunt, Soledad, who knows she’s being taken to participate in a ritual and seems ambivalent about it, is harangued by her aunt for not wearing lipstick, is reminded that her youth is fleeting and that she needs to dress more like a woman. Her depression seems more practically local than existential, and there is a sad irony in being driven to a place meant to heal you while being actively belittled by your healer.

Arriving at her grandmother’s house to begin the ritual, Soledad is immediately asked if she’s gained weight. The actor who plays Soledad is an expert at conveying the most discouragingly withered blank face. A pigeon is the crux of the ceremony. Soledad is meant to hold it in her hands then let it go. With all three women dressed in white and heading towards the beach, Soledad’s grandmother reminds her how important it is that she doesn’t look back at the pigeon once she’s let it go.

On the beach the aunt and grandmother begin the ceremony, drinking alcohol and talking though as possessed. The conversation is about expelling bad energy, and only allowing good energy to enter. When Soledad lets go of the bird, it lands just a few feet away. As her aunt and grandmother walk ahead of her, Soledad does what she was warned against, and looks back at the bird. As soon as the three women arrive back at the house, the phone rings. It’s her grandmother’s medium calling from Puerto Rico for Soledad. She asks one question, “Why did you look back?” For a minute and a half, Soledad stares at the camera while being comforted by her grandmother’s medium. Played by a great actor, Soledad listens and stares, her face withstanding an avalanche of tears. Why Did You Look Back elicited many feelings in me, and I like feelings in art. And beauty.

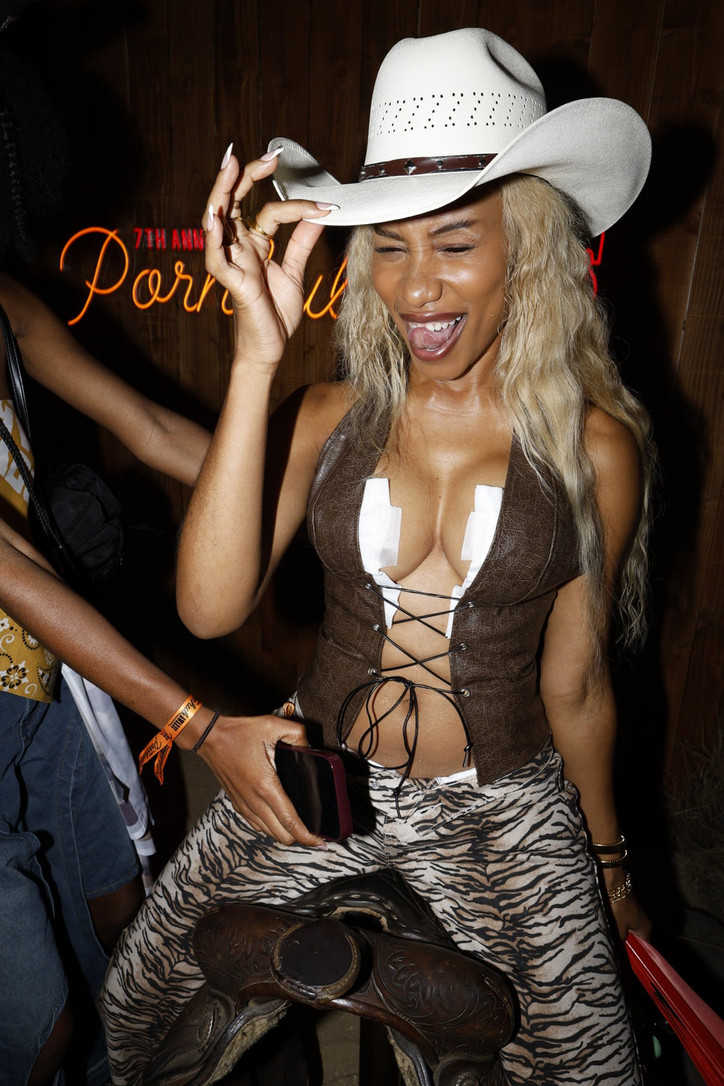

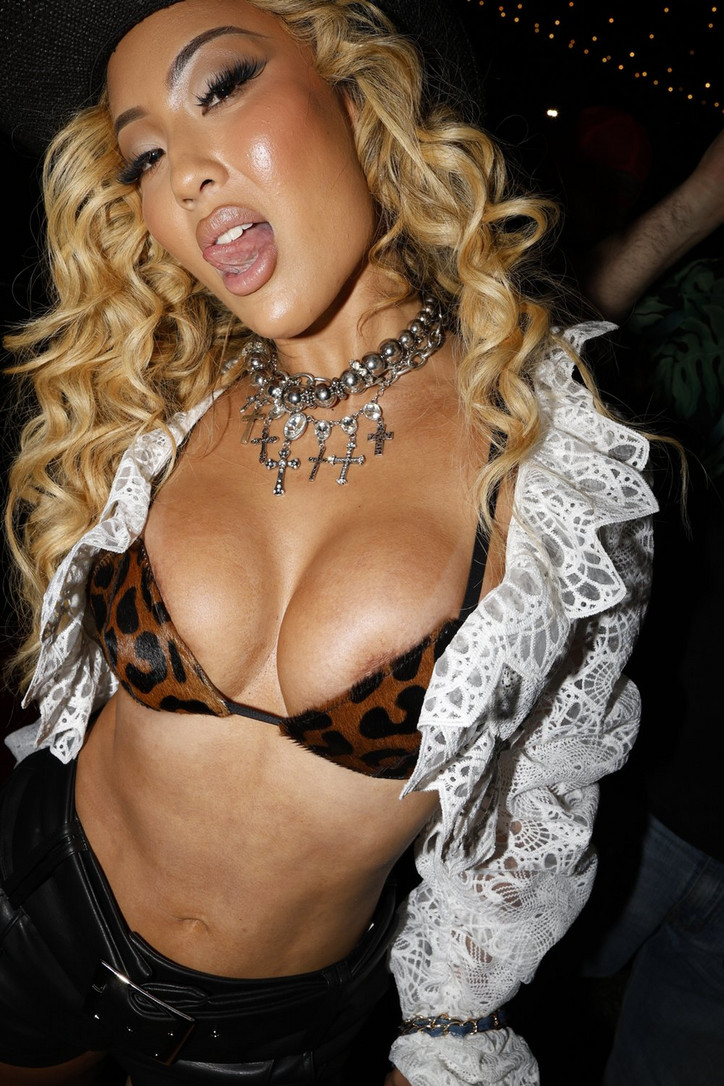

In my last night in Miami, we were all taken to Santa’s Enchanted Forest. I’d never considered what Christmas would be like in a place without snow. Everyone was relaxed and throwing money at rigged games. This last image could stand-in for what my experience in Miami felt like, and maybe looks like a still from a movie I’ll never make.