So tell me about this pilgrimage you’re going on.

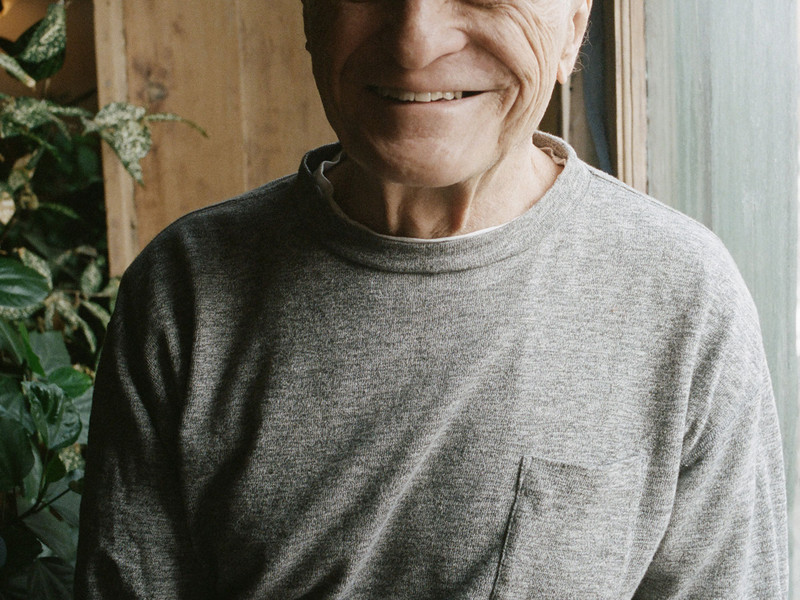

Ten years ago, I first read Anne Carson's essay “Kinds of Water,” which is her account of walking the Camino de Santiago. I’d say that this piece of writing has most influenced my own, as well as the ways I think about research and citation. So the pilgrimage to Compostela is something that I’ve held in my mind for years as a poetic abstract, and this year took on as a tangible act. My life felt aligned for it. Anne Carson did her pilgrimage with a man she loved who did not love her back, while she was dealing with the slow loss of her father to dementia. I am doing my pilgrimage with my best friend of ten years, while trying to take stock of my triumphs and losses as an artist, lover, friend, offspring, and addict.

A pilgrimage is a spiritual thing, but it is also just a thing to do. The undertaking is formidable but straightforward. I like this as an expression of faith. I grew up in a secular home; my parents did not grow up with organized religion because they were in Communist China. So my limited exposure to religious practice was more social and textural. For instance, in China where I spent summers as a child, as our weekend activity we went up the mountain to the temples where we lit incense and prayed for wealth, abundance, and good health. Beyond that, I was not familiar with any kind of devotional or spiritual practice. Growing up in the US, going to public school in the suburbs, I vaguely understood that some people went to church or synagogue on the weekends. It was not until I was in second grade that I learned that Christmas — which I understood only to signal time off from school and a conifer in the foyer — was a religious holiday that had to do with something called Jesus.

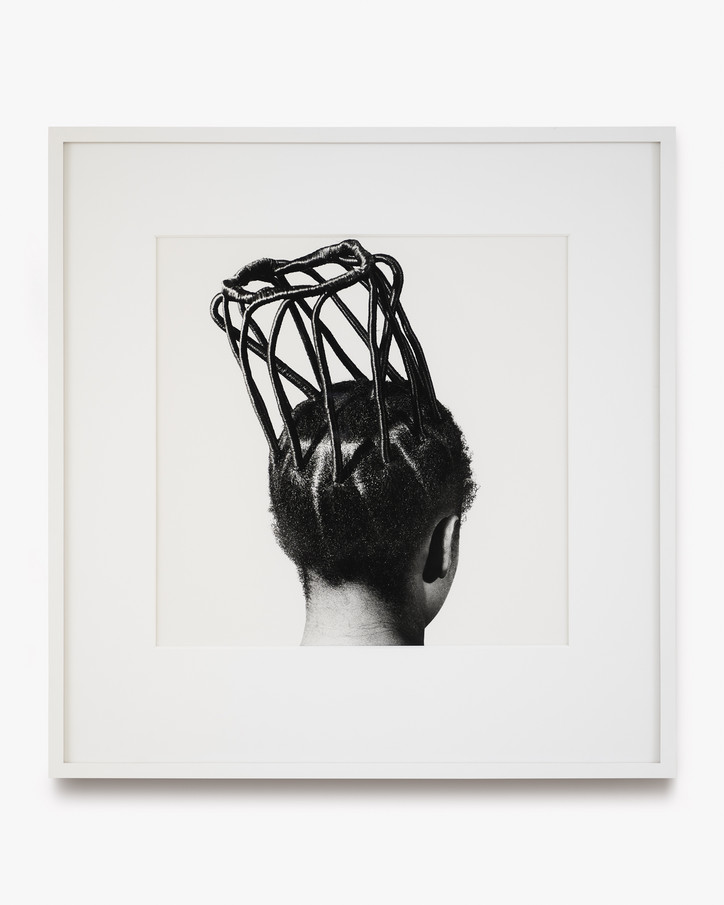

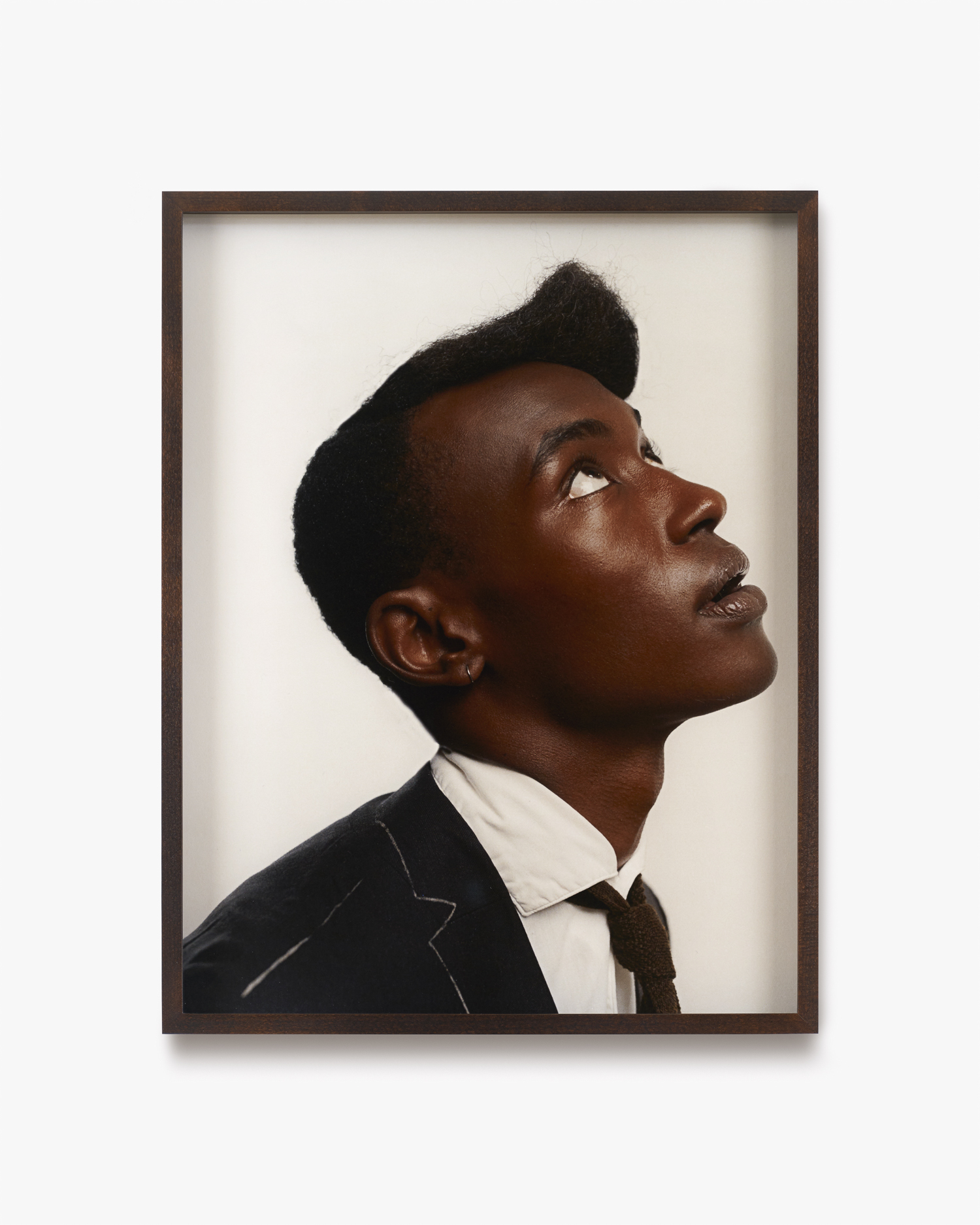

In my young adulthood, studying Western art history, I learned about the Bible and the Church. Those stories about saints and the material manifestations of Catholic belief — the sensual, erotic ritual of them — interested me. I think that arose from both my interest in Anne Carson, who is a very spiritual writer, but also the period of my early twenties where I was working a lot with Chinese mythology and thinking about the impulses behind the creation of these belief systems. They were ways of lending structure to overwhelming longing and fear. While I could not necessarily understand a literal belief in God or the cruelties of organized religion, I could understand intense, transportive desire, and the ecstasies of self-flagellation and martyrdom. So now, perhaps in an attempt to apprehend something I am not yet aware is within me, I choose to walk the Camino.

It’s interesting hearing you speak about Catholicism from this perspective — removed enough to recognize its aesthetic and symbolic meanings and its relation to desire. It reminds me of this one line in Carson’s “The Truth About God”: "My religion makes no sense and does not help me. Therefore, I pursue it. When we see how simple it would have been, we will trash ourselves." Are desire and suffering all that different if one can lead to the other? Is it the pursuit of a thing that gives meaning? There’s the line in the press release about your show: "I have never felt guilt, but I have felt the suffering of others."

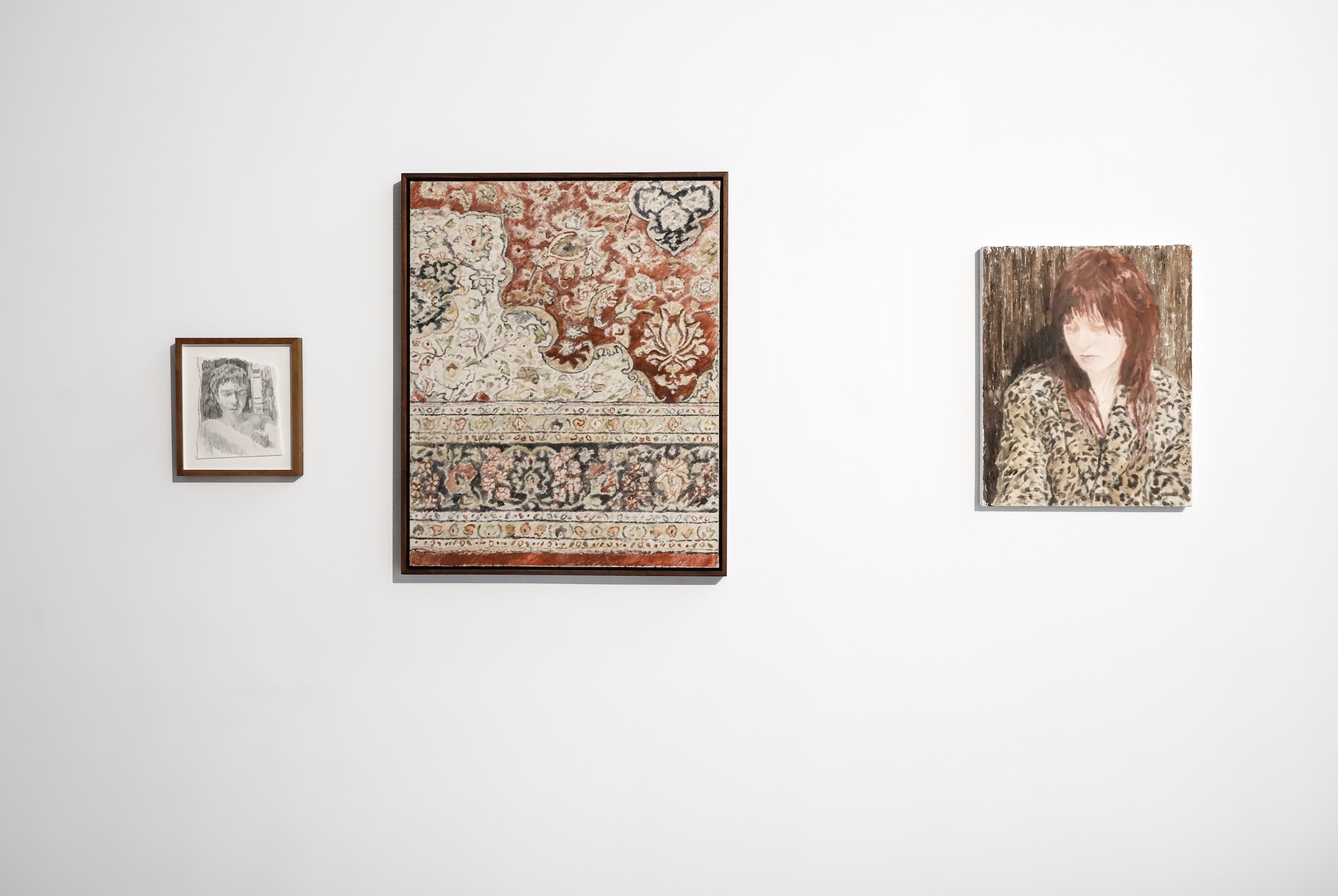

Is suffering a central tenet of Trick and what does that mean in your practice more generally?

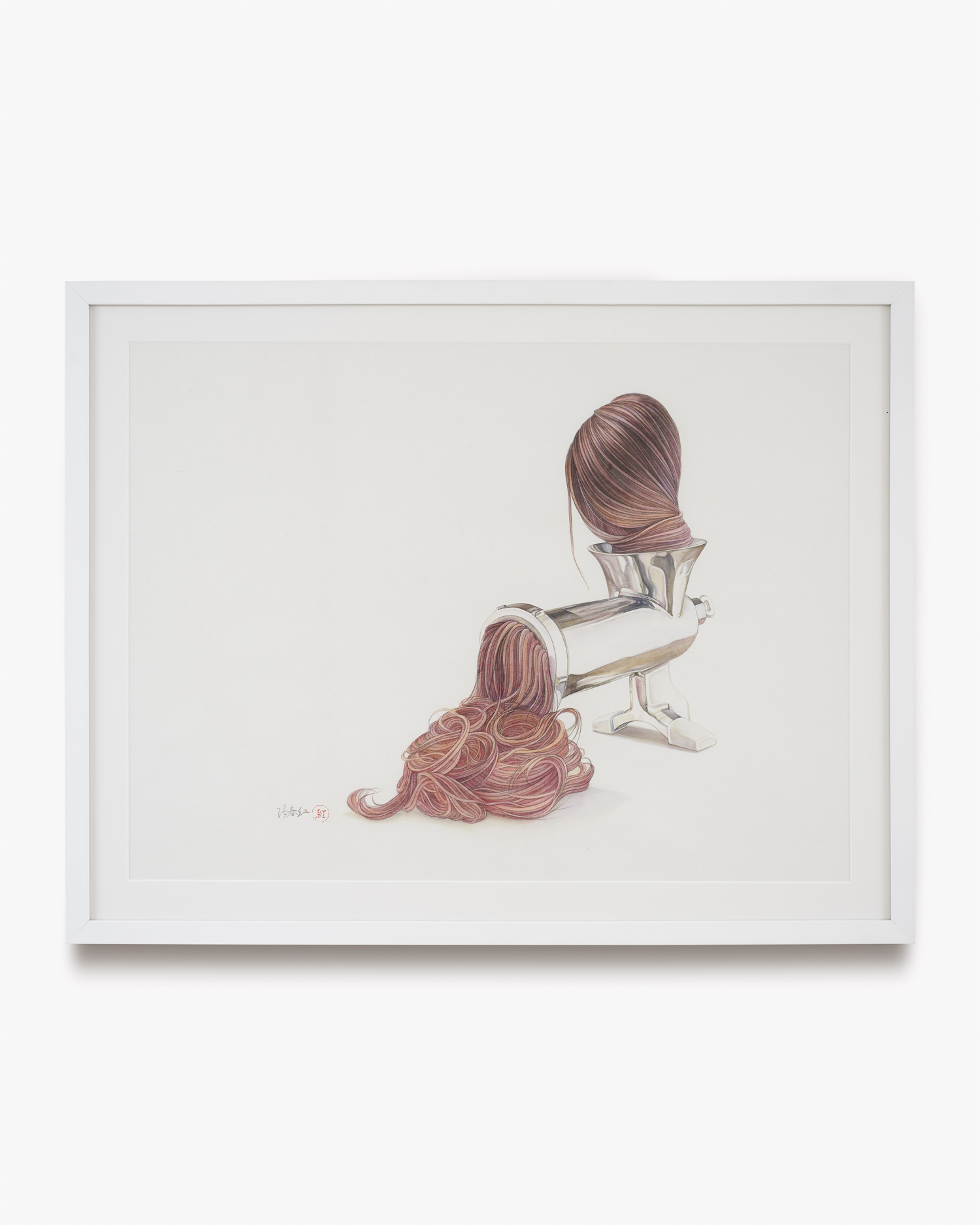

Maybe not so much suffering in itself, but equivocation and simultaneity. Rapture and pleasure are inextricable from suffering and horror; it's about extremity, it's about intensity.