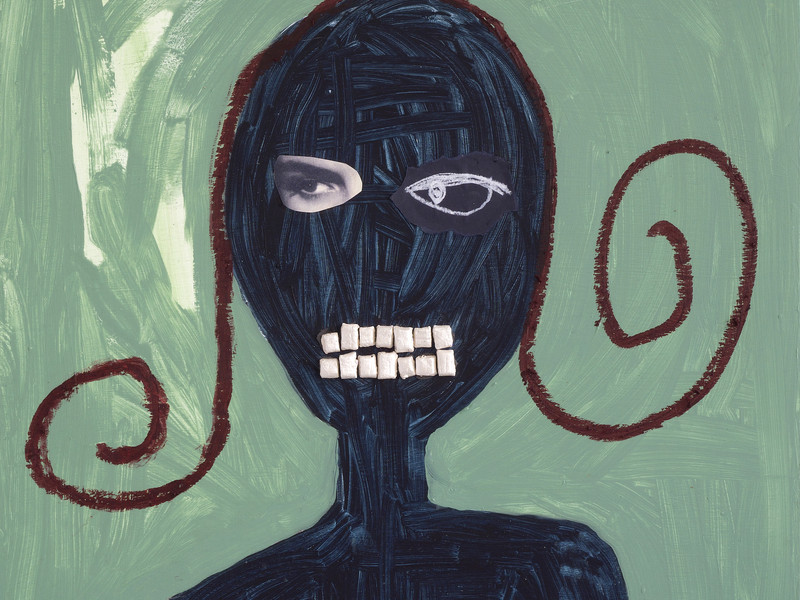

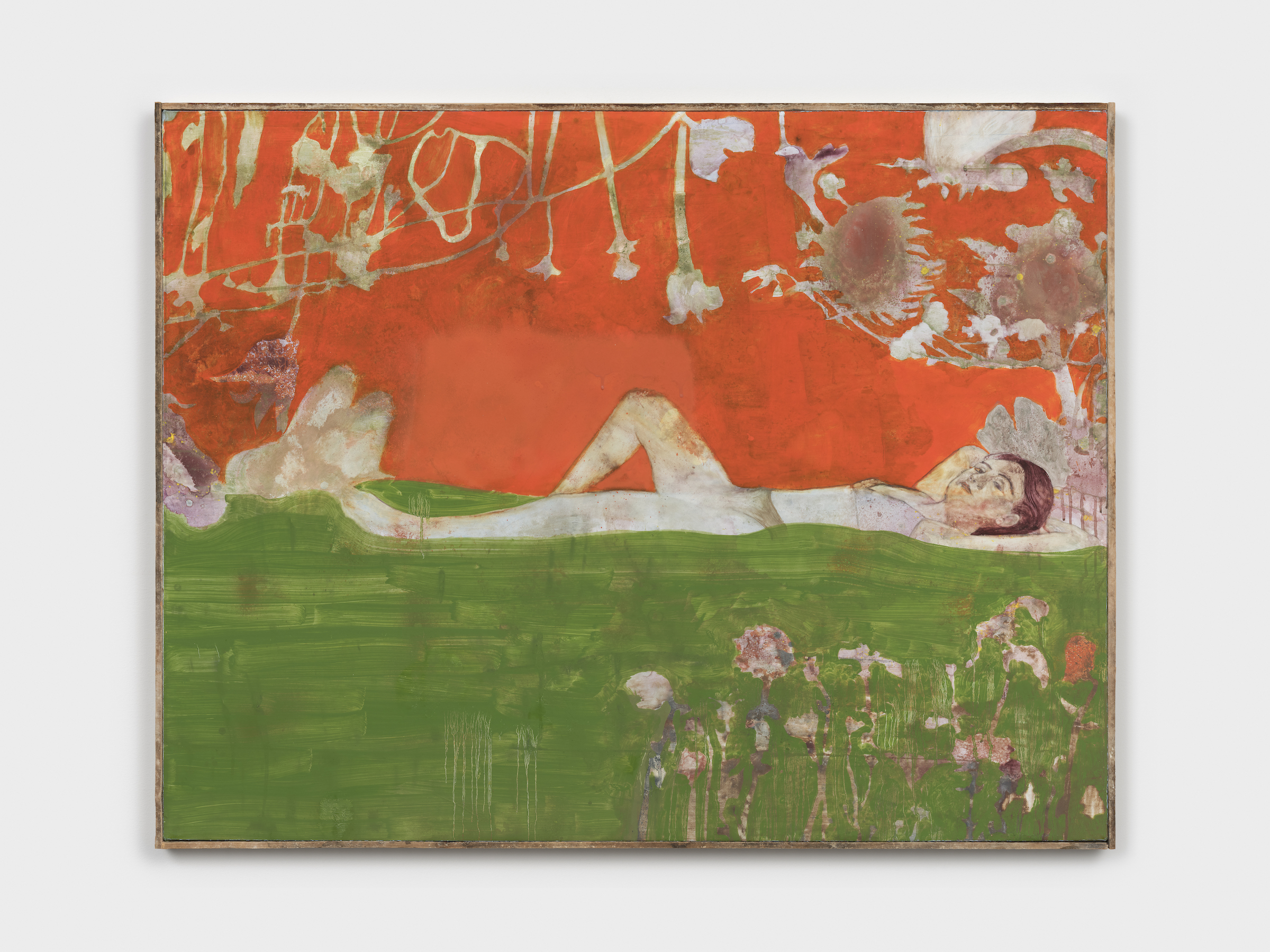

Bolding’s attraction to gestures of chance and accident can be attributed to his close studies of the highest arena of 20th century German cultural wars, where deskilled conceptual painters like Jutta Koether and Charline von Heyl, closely associated with the underground art scenes of Cologne and Dusseldorf, vigorously attacked conservative representational regimes within the established art world and quickly ascended into stardom. The lyricism and collaborative impulse found in Casey’s paintings could be traced back to Milton Avery, whose fondness for unrestrained use of colors and expressionist figuration lifted the American tradition of abstraction out of obscurity and into European museums. But perhaps the most fascinating of all of Casey’s influences is the most lowbrow: his time spent working for his uncle’s faux finishing company that covers the plain walls of middle-class households in Colorado with Tuscan style decorative patterns.

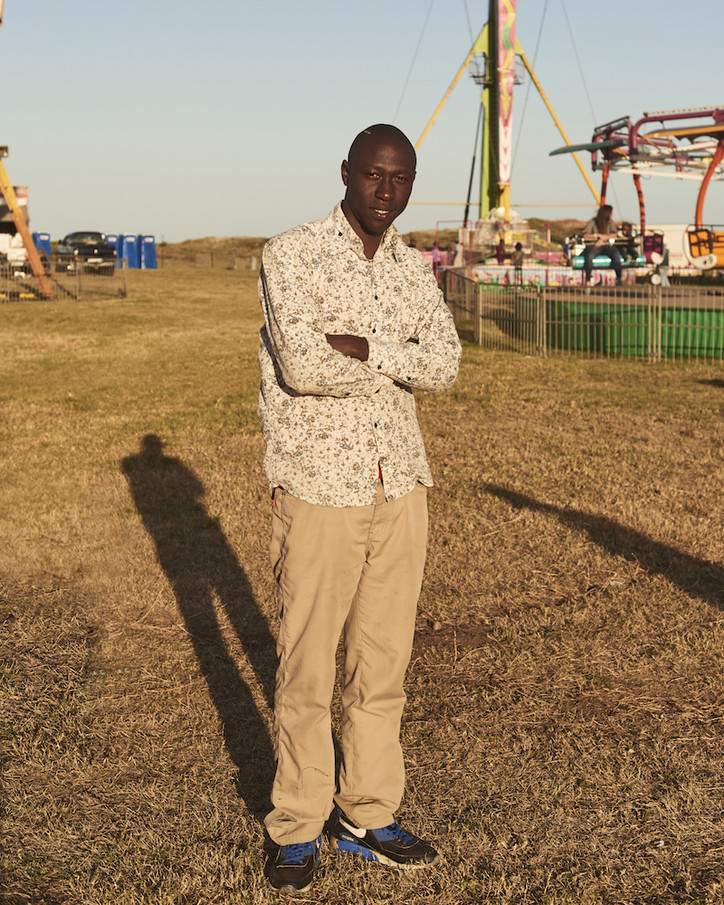

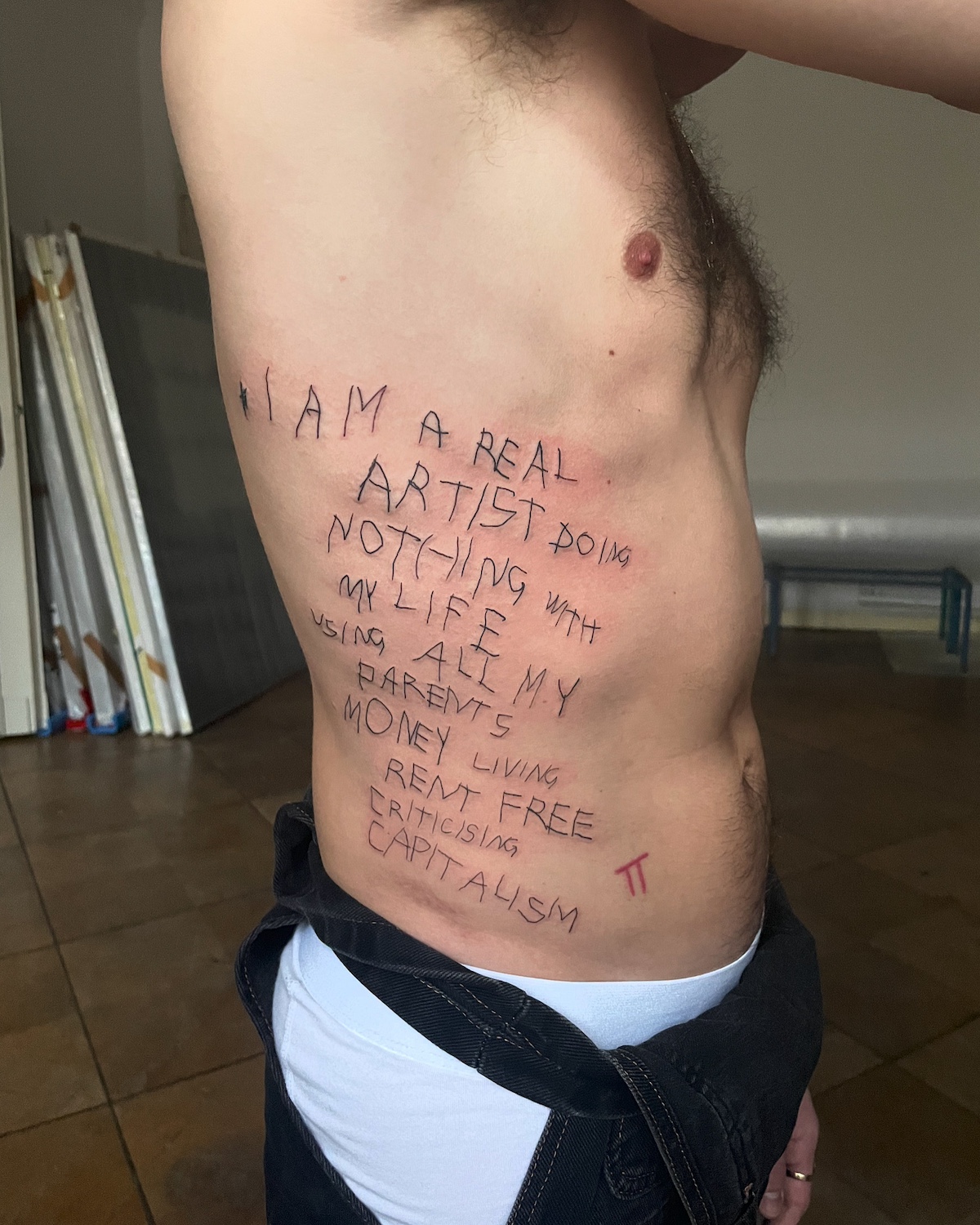

When Bolding invited me to his solo exhibition, I went in with a reluctant curiosity, as I have been a fan of his practice for a while but remained wary of how art history tends to monumentalize white male painters and mercifully allows for their self-mythologization. After an hour, I came out of the meeting with a completely different understanding of Bolding’s position within the art world. He is candid without being contrarian and sincere without being pretentious, seemingly propelled by a tender attention to social relations and concerns that often fall outside the priorities of the New York gallery circuit.