Dirty Nerd

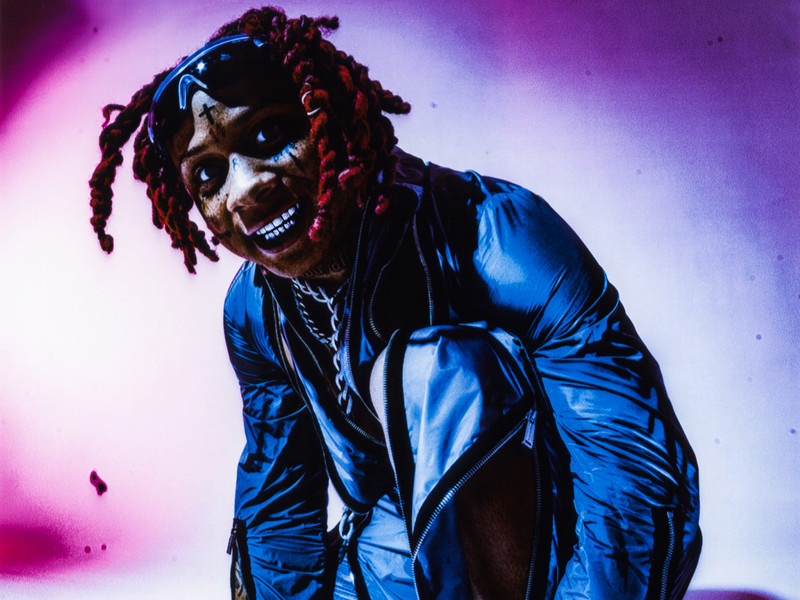

At the intersection of Broadway and Lispenard, he says that the music is what makes it all worth it. It seems so. He spends the photoshoot with a pair of overhead studio headphones draped around his neck, and whether talking through his distrust for wireless earbuds in the elevator, analyzing the structural makeup of my tape recorder in the office, or bemoaning the hordes of sound equipment littering his apartment in the lobby, every time it’s slightly applicable for him to geek out about something sonic, there’s a riveting mini-monologue that follows. In a recent piece he wrote for Medium — his first after being banned from the site for a militant essay its editors didn’t take well to a few years back — Dirty Bird asserted, in parentheses, as side-commentary to a larger story about a hypothetical man who forges a license plate, that “(being a nerd really comes in handy).” With the looming shockwave of a push his career is foreseeably bound to undergo in the coming months, being the nerd he is about his job certainly wouldn’t hurt. “It’s been hard to disengage and just be a regular n***a,” he says, leaning back on a couch inside. “I used to have those moments where I would come home from my tour and go to my friend’s house, and we would smoke on his grandma’s porch. And I’d be like, Yes. Now I’m just me. I can just chill. I’m not a fucking superstar, I’m not a DJ, I’m just a regular n***a who’s smoking weed on his friend’s grandma’s porch. Those were the moments that I really cherished last year. This year I haven’t really had those.”

And with the way things are going, he likely won’t have them again for a long time. The past few months have been fast. In May, he played two shows in Montreal, then came home for a week or so before packing up for Portugal in early June to perform in Lisbon, after which he trekked to California for a pair of concerts in Los Angeles and Oakland with fellow tech-savvy ravers Swami Sound and Daze, only recently venturing back across the US in time for the East Coast leg of his high-energy international antics. (Did you have trouble reading the previous sentence? Now try living it out.) The premise for his being in New York was last night’s aforementioned 4 AM bash — an event dubbed “Shrek Rave,” the tagline of which was “It’s dumb, just have fun!” — and as soon as he finally gets to leave here and spend a few weeks at home, he’ll find himself right back in the Big Apple for a pop-up event, after which he’s slated to begin putting the pieces together for his upcoming tour. A lyric that comes up in conversation is one from Earl Sweatshirt’s “Burgundy,” where the young phenom, then grappling with the trappings of newfound stature, spits: “My grandma’s passing, but I’m too busy getting this fucking album cracking to see her.” Dirty Bird relates to this on two fronts: (1) his grandmother recently passed away, and (2) things are about to start moving so quickly — if they haven’t already — that extremely personal priorities like, say, mourning the death of a family member, might just wind up taking a forced backseat… one where the crazed driver, who may as well be blindfolded, is an industry drooling for more of what Dirty Bird calls "cultural product." The only time to figure it out is while it's happening. Whichever way you cut it, he's going to have to walk a thin tightrope covered in fog — and much sooner than later.

Something he's working on is the ability to ask for help. “I’m glad I’m able to make relationships like that — I’ve been chopping it up with KeiyaA lately, I’m trying to link up with her today, hopefully — and I think what will have to happen is that I will have to become more comfortable asking them how to deal with stuff like that,” he says, after running through a list of idols, including Earl Sweatshirt and Black Noi$e, that have become his friends in “full-circle” moments spanning over the past several months. “Or just learning to be more vocal about how I’m feeling. Maybe just with my friends. Like, Yo, this is how I’m feeling. I think talking about it more would make it easier. I’ve been definitely working on that lately, working on telling my friends how I feel about stuff. I was very private for a long time — which was healthy for me, growing up — but now I think I need to re-evaluate.”

Even for someone as comfortable with switching things up musically as Dirty Bird is, it’s an awkward development to suddenly have to translate a similar structural malleability to real life. In explaining to me the “mission statement” of his sonic footprint up to now, he thinks a bit for the right analogy, then settles on the “Polymerization” card from Yu-Gi-Oh!, which fuses two monsters together to make a bigger and more powerful one — a comparison Justain pauses his Nintendo Switch to express emphatic agreement with. The track that introduced most to Dirty Bird is “Expensive Taste,” a bouncy number featuring benchday that oozes with the ebbs of fleeting nights spent in rented Cadillacs, carried by a slap-bass sample as buoyant as the high-heeled legs it's hypnotized into gyration on countless (and counting) underground dance floors across the globe. Dig deeper through his geekily-expansive catalog, though, and “Expensive Taste” looks less like a microcosm of his sound and more like one of its several limbs — the Roy Ayers-sampling “2000,” from his 2021 project Time Traveler, hits like something a Moodyman-mentored Gil Scott-Heron would release in 2050; 2020’s “E-Dating” sounds like music your old-school hip-hop loving, Higdon-hat wearing Black grandfather would have sex with your grandma to after you put him onto lo-fi; early deep cut “Bushwick” sounds like the stuff of a hornier Les Sins toting a Daft Punk-informed penchant for underwater-sounding bass notes — which, in the grand scheme of things, comprises a body hellbent on reckoning, or “polymerizing,” the past with the future. He isn’t satisfied until he’s made as many cultural lines intersect as possible, and whether you understand the end product or not doesn’t concern him nearly as much as whether he did what he set out to do.

Wagenmuzik, the danceable EP Dirty Bird’s slated to put out this week, is a notable step away from the experiment-based approach he’s taken to music in the past, and into a mode of intentional palatability. “It’s a little bit more accessible — when people say ah, this music’s accessible, what it really means is that it’s easy to listen to, and it doesn’t challenge your listening palette,” he says. “...Which is not usually something I try to achieve with my music. Sometimes, I want to have the most esoteric thing possible. I want to be a little challenging. I’m okay if people don’t like it on the first listen. But this– it’s easily likable, it’s fun on the first listen, it’s fucking poppy dance music. And usually, I don’t like making poppy dance music, but this is fun, it’s cool, it’s summer. It’s a cool project and a cool point in my life.”

The record is something you can get away with playing front-to-back at a DJing gig without anyone batting an eye, and, both sonically and thematically, it feels like a newer, more self-assured lurch forward for an artist formerly revered for his scatterbrained sonic habits. In a sense, Dirty Bird seems to have put in the time — four years to be exact — to do his artistic homework, and on the tail end of an extended period of trial-and-error, experimentation, and self-scrutiny at every misstep, is finally getting things in place to brace for the hyper-commercial turning point his studious approach has earned him. For now, in the calm before he takes on the trappings of blowing up, he has material things to hold close: “I got the BMW!” He exegetes Wagenmuzik’s namesake with a lofty laugh. “So it’s kind of, like, commemorating this summer of my life on a high note. I have the material happiness and the existential happiness.”

Dirty Bird has always been happier than most, but for him, this is a new kind of joy. Born in North Carolina, he lived in poverty for most-to-all of his adolescence, although he doesn’t remember ever feeling particularly sad about it — a detail he credits to the hard work of his parents to ensure that his childhood was a positive one. He grew up with a passion for technology, and planned for years to go to school for computer science, only to change his mind at the last minute and study studio art at New York University. As much as it upset mom and dad, it grew to be a crucial turning point in what had been, up to then, an existentially-challenging journey to find out what he wanted to do with his passions, and, especially in the South, how to make it happen. “My parents didn’t get it for a while,” he explains, “until,” much like Black moms and pops nationwide, “I started making money.” He continues: “I would literally rather be a broke-ass n***a trying to be an artist than to be in spiritual pain trying to do some shit that I don’t want to do.”

So, he went the route with less spiritual anguish. For the first two years of his career, he sought to prove to himself that he had “made it” via material objects, a habit he links to a long Black lineage of motions to ventriloquize one’s actually-fictitious social mobility through the acquisition of physical markers. It would be wrong to call his next move an “odd job” — a term music journalism loves to slap onto whatever it is artists do before they make it big — though, because it was another calling of his, and one all of his art somewhat serves as a living testament to: education. He taught at a local middle school that, especially because it was a sister institution to the one he attended growing up, placed him in the strange position of looking into an existential mirror every day. Everywhere he turned, he saw himself. He quickly became a favorite of his students, partly because of the chill older cousin-esque power dynamic created by his young age (22, when he first started). But that only made the dread of not being able to help them worse. “They’re reflecting my traumas, and I’m reflecting their traumas, on a daily basis,” he says. “It wasn’t healthy. It’s not healthy for any Black person to be in that kind of situation, I would say. Especially when neither party has had the time to have the therapy necessary. The kids needed therapy, I needed therapy. It’s rough. Because everybody needs help.”

Dirty Bird eventually left his teaching job to pursue music full-time. (He remains in touch with former students, one of which he helped with an early-college homework assignment two weeks ago.) As much as he’s escaped the version of it that existed within that school’s walls, though, he still hasn’t entirely cleared the mantle of being the helper who also happens to need help. The clean-cut, newly-palatable sonic approach he’s taking with both Wagenmuzik and the full-length LP slated to follow it will serve as a “helper” to ears ill-trained for his archivist machinations at full strength — which, at the same time that it creates a wider audience, also creates the burden of dealing with it. For the moment, the assistance he’s getting is on the management side of things. “I think I definitely will be in a different stage in my career,” he says of this next stretch of releases, “at least PR-wise. And I think that is going to feel weird to me. Just because up until now, I’ve been kind of freestyling. I just got my first real manager a couple of months ago. I’m about to get a booking agent after this month. Shit is about to get a little more serious.”

It’s not like he doesn’t already take his work quite seriously. A spiel he’s heard, and grown to increasingly bemoan, over the past several years — from casual web interactions to meetings with record labels — is one that goes something like You’re so funny on Twitter and to our surprise it turns out you actually make music too and we’re big fans and you get the idea. Dirty Bird has had thousands of followers on Twitter since high school, and has been living almost exclusively on the internet since he was about 4 years old, but as the spotlight ever-so-gradually grows brighter and hotter, he’s begun to reckon with what it means for his artistic and human identities writ large. “It actually freaked me out and I had a panic attack for, like, a week, and I drove to the beach and slept in my car for two days,” he says of prior struggles with his online presence. “Because I was just so freaked out by the fact that I was so hyper-visible and not knowing it… How the fuck was I supposed to know that n***as and all these record labels in Beverly Hills and shit knew me because of some bullshit stupid shit I tweeted high at 3 in the morning?” As things get more serious, and the pairs of eyes on him multiply, Dirty Bird is looking to take every opportunity he can to slow things down. A day after our interview, he’s set to go on a fishing trip with his closest friends — and no business talk will be allowed.

Although it is, incidentally, a great marker for where Dirty Bird is in his career — when business talk is allowed, it’s usually two things at once: (1) laudatory, and (2) coming from other people. Something he’s intent on is the idea that you must have a level of ego to be an artist in any capacity. “If you don’t have ego, you can’t make artwork,” he explains, because “making artwork is a very selfish endeavor. You’re wasting resources to make something that nobody asked you to make. And then you’re going to ask people who never asked you to make that thing to give you money for it.” Ego certainly shouldn’t be an issue by the numbers — whether you’re looking at his Twitter following, or the monthly listeners on his Spotify page — but rather than actively do business by giving himself certain titles, he’s grown to simply pick out whichever of the various anointings constantly being thrown at him fit best, and embrace those callings as his own. When publications began dubbing him “Afro-futurist” early on, for instance, he assessed the mantle for a bit, made a decision as to whether it applied, then began to proudly don the inscription. He resolves that “Now I’m in the embracing stage of my career. I’m embracing all the things that are true about me.”

Something he’s also embracing is that, sometime soon, to some extent, he’s going to have to give up complete control over his artistry and the management of it — a process he’s already started. Dirty Bird vehemently admits that he prefers to manage most things on his own, and one of the most telling testaments to this nature is the website he’s put together, gum.studio, as a means to give fans a single place to buy his tickets, cop his crafts, and get timely updates. His display name on Twitter is a golden minidisc, something that doubles as yet another indicator of his nerdiness for sonic paraphernalia, and also a bit of an unlikely trademark. A trademark, because he prides himself on what’s become a signature custom to purchase, prepare, and package his own CDs for sale directly from his home — a pursuit just as nerdy as it is profitable. “I am absolutely a control freak,” he says, laughing. “And it started because I was using a bunch of really– I’m a nerd, obviously, right? There are these CDs called Taiyo Yuden, Japanese-based CDs with blue dyed ink on the side that you print data on. They’re extremely high quality, and they were the industry standard for a couple of years, but not anymore, so they’re kind of hard to find. I was very intent on using those CDs specifically. And that’s why I was making the CDs myself. It’s just some fucking stupid nerd shit.”

Nerd shit and material objects are two vital factors to Dirty Bird’s growing lore, and the only element that was missing beforehand — money — is soon to come rolling in more than it ever has. “Until my order numbers get too high for me to keep doing it on my own, I’m going to keep doing it myself,” he says. Production of Wagenmuzik physicals has already been outsourced.