Hell is the A Train Platform at 3AM

Talk to me about what was being addressed at your Armory performance.

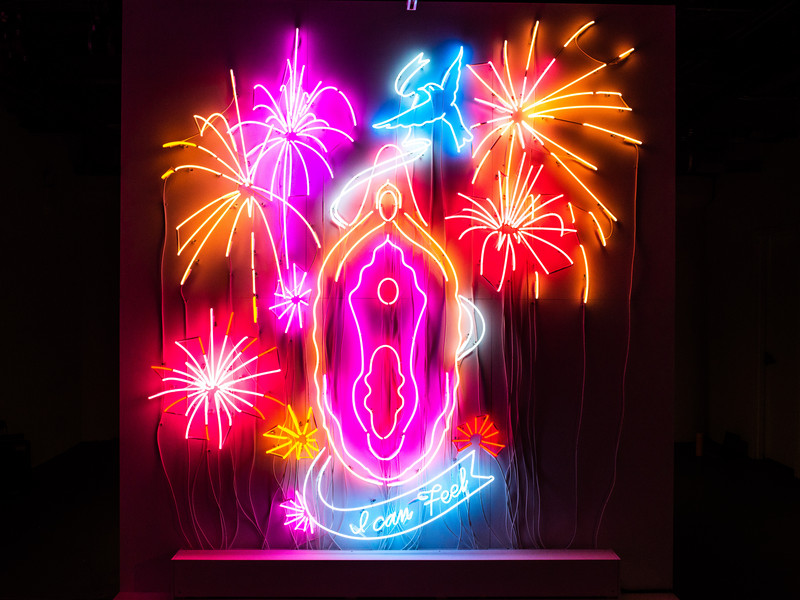

Well, It’s basically [the result of] an evolution. So, I started this piece—well one part of it, the performance, has totally changed since its original form—but basically, I started writing and thinking because I was invited to a festival that I really love in Glasgow at the very end of 2016. I really love the people who throw the festival and they had proposed an interesting idea to me—the loose idea around the conference was how to challenge or undermine ideas of power, but thinking critically about conventional ways in which people formulate those ideas. And specifically, thinking of the idea of a body—that was one of the subtexts of the conference. Like, what does a body mean? Does a body actually exist? When we say we have a body, does that involve a distinction with the outside world? There’s mind-body division. There’s also the idea that our body represents our relation to the state, and that there are an inherent set of rights attached to a body as a static and cohesive thing. So, the counter proposal was to find other ways of thinking of a body and thinking of ways that are actually a line in which that sort of fantasy is fabricated—whether its fabricated in law or literally, the way we talk about rights.

Fred Moten is a thinker who has written at length about this. If you’re thinking about something like blackness, how do you conceive of the notion of a rights bearing subject with a rights bearing body when you clearly have a long history of entire populations of people who have had that very notion completely unmasked in the sense that people were living as chattel? Not to say that rejects some inherent humanity of people, but in terms of the law, people were totally erased and that body meant nothing. That body signified a refusal of a coherent idea of rights. So, that was the loose theoretical starting point for the performance. I wanted to think about ways that plays out.

So, you originally created this piece for the Glasgow performance?

There’s one section in that festival performance, which is the one piece of the original performance that carries through to the Armory, about the train. And it talks about being on the train and it’s this experience of—I don’t know if everyone has experienced this but I know I have—whether it's sexual harassment, a rapey vibe, a homophobic vibe, or a transphobic vibe, a racist vibe—whatever. And being on the train is the example I use because it’s so specific to the past. In my adult life, since I was 18 years old, the train has played a central part in how I relate to the world around me. There’s that feeling when you sense a imminent threat or imminent violence and you realize there is only so much your so called ‘body’ will be able to do for you. Like, the idea of a right ceases to exist at the moment you realize that you have no defense mechanism; when someone takes your life a right ceases to exist; when someone threatens you, even in your head, a right as something real ceases to exist. And in the same way, a body really ceases to exist as a limit point, too. So, I wanted to think about flesh and fleshliness as an alternative [to the term ‘body’]. That's partially taken from some of the reading I did in preparation for that conference—the idea of flesh, and wanting to escape your body, or the body as a trap, as an allusion to this statement that ultimately you're a sack of flesh, which you could think of as negative, but that was kind of the starting point. So, basically I was thinking about fleshliness.

I had done other performances that weren't really related to that but when I had the opportunity to do something new, I thought of it as an opportunity to update that. So, for this performance there was a lot of new music. New text, because the original performance was focused more on danger, or perceived violence—i was all under the pretense of things that are related to some sort of violence. So, for this performance I was thinking of other ways that fleshliness could exist. I've been in a romantic mood lately, so I was also thinking about the dissolution of a body as the limit point, as a self-contained unit, that then contains a brain. Another way of projecting that is to encounter experiences with love and identification, whether that be with friends, whether that be racial identification, whether that be the dissolution of identity into a group, whether that be taking LSD. There are a lot of ways where the idea of a body as a limit and a self-contained entity that demands things like rights or—even thinking of things medically—that you would understand what you're touching is the only way to address an ailment. So, I was thinking a lot about those things and the performance kind of expanded. Also, I’ve been making music because I’m releasing music next year. So, performances are a really nice opportunity for me to practice. I haven't performed in New York in three years—I did one show at the Rubin Museum, but aside from that I haven't performed in New York at all since my Performa piece, which is strange.

And that was 2015, right?

That was 2015. Also included in the Armory performance was a section on WorldstarHipHop. I was thinking of Worldstar and the denial and invisibility and the refusal to recognize the constant erasure of black women’s bodies. And I think—specifically when thinking about black women—the notion of flesh and opposition to a body as some sort of rights bearing cohesive thing becomes really clear. Because so many videos on WorldStar are of black women.

Right. Videos of women being harassed or disrespected.

Or getting the shit beat out of them. Like 80 guys are just basically like—some might say ‘running a train’ and some might say raping. Real mental breaks, women having real mental breaks, and a lot of the times its voluntary and I relate to that—being in that moment of desiring your own extermination in one sense, because extermination is at least a moment where you feel real. And I think part of that feeling is related, as well, because that's when you are just flesh. So, to be in a moment when you are reduced to just flesh might feel exhilarating and free in the sense that it feels like something true. You know what I mean? In the way that walking around in a body that is constantly denied of all of the privileges and entitlements that are supposed to come with the body, it might feel more real, like more truth, to videotape that experience and put it on WorldStar. And honestly, I think the culture of WorldStar is disgusting but it really makes sense. That was a primary place—a sight of encounter—where I was thinking about the difference between fleshliness and bodies, and rights and violence, and the moment where all of these things come crashing into each other. And then at the end of the last part, which is the Worldstar part, it's about the basic question of wanting to be intelligible, wanting to be rendered. The desire for other people to engage you and have the cognitive ability to see and understand and treat you as a fully present, sentient being—it doesn't need to be human specifically. So, these are the pieces of the questions that the performance dealt with—different ways of thinking and through that.

With the WorldStar section of the performance there was a line that you deliver: “It’s violence you crave from a scene struggling to escape your own snuff film.” People’s rights are ignored and their bodies prevent those rights from being extended to actually being real. So, in these moments where you’re being degraded or brutalized that's when you might feel like your most ‘real’ as a person, because its authentic.

A sense of truth.

What about the space that your work is presented in—how does that affect its impact or how it’s perceived?

Generally, I'm down to perform anywhere as long as I feel like I don't have to compromise what I’m doing. I think there are advantages and disadvantages of being in different spaces. Part of the reason why I haven't done the type of performance that I did last night, why that hasn't happened in New York, is because there aren’t really resources. Like, if I want to just do a little thing and play a backing track and have Joe drum with me, I can do that in New York, but the resources here are much more stratified in the sense that it’s either the basement at the Spectrum or the Guggenheim or Park Avenue Armory. I haven't seen a model of making it work differently here versus spaces that exist in other places. So, I find in New York specifically for performing, if I want to do something of a certain scale or a level of production, it just has to be in an institution. The same cost of renting lights in New York is like half that in other cities—like renting a disco ball and having LED. It’s so expensive.

It’s hard to find middle ground between a space like Spectrum and the New Museum. In New York there's aren’t really a lot of options for that. Do you have a preference for what kind of space your work is shown in?

I don't necessarily have a preference. I like having the option of doing different things. I mean, that's what I’m working on making the performance become—or at least a certain type of performance has to become more and more about the music and the way that I write the texts are more lyrical. That’s one of the reasons I’m so excited to release this new music—because music can be less about performance and it can just be a show or a concert. I think I realized that a lot of what was happening was, sometimes I'm in a museum or institutional construct and they're like, ‘Oh it’s performance art,’ and I’m like, ‘Actually it's just a concert, but whatever you want to call it.’ So, I think releasing music will be nice because it will allow the musicality of it to be how it circulates instead of just everything I do—even if it's basically a concert—being under the guise of performance art. Although I like that because I do think it is performance too, but you know what I mean.

Of course. Performance is always an aspect, but sometimes you want the music to be at the forefront.

I think it will be interesting to release music and see how what I do mutates and travels because it will be a little less of a stratified experience. Because performance and things that I have done before have been in art context, and in an art context, questions of circulation can be a difficult thing.

Absolutely. And if your music is available on the go or wherever listeners are then that sort of alleviates any stratification and they can experience it wherever they might be. Also in terms of your music, you’ve been shaping the New York City nightlife scene for a number of years now. I used to see you spin at 11:11 a lot and I would get my whole life to your sets. What do you think is in store for the future of nightlife in the city?

I feel right now—and I dont think it’s a bad thing, because this is how I felt around 2010 when I graduated from school—but I sort of feel it's much better than it was then. Generally speaking, it’s much, much better. I have a feeling that things are just being figured out. There was a long time when I first got started that you had the ‘impresario’ model for who really threw parties. There was 285 Kent, there was Glasslands, and I loved them, but at that time, I would say between 2008 through 2010, there was cute stuff happening but it was really hard to get things off the ground, and I just felt like, ‘Yeah I’m hanging out at bars and going to parties but nothing is really hitting the spot.’ I had this feeling that in terms of real estate, venues and musical identities, there were a lot of questions that felt unresolved. And I’m really glad that I came up during that, when you had people just doing more stuff. You had [parties like] GHE20G0TH1K and there was a real sense of identity. I started throwing my party—

Shock Value.

Yeah, and it was like, ‘Oh we do shows during the day,’ and then, ‘We throw parties at night’—at least the type of parties that were my favorite. And then, if you were looking at something like Shade—technically there's Red Bull money behind it, but essentially it's an illegal party. I felt that the chokehold that police culture placed on New York—people were really responding to it. It was fun and I think that was the period when I was like, ‘I’m really in my New York identity.’ I loved throwing Shock Value, I loved throwing other parties. It was also annoying—dealing with illegal venues obviously has its downsides. I remember after the Ghost Ship fire happened in Oakland, all of the DIY venues got shut down, except for maybe Spectrum, which had just moved, but literally I would find a new venue, throw a party there and it would get shut down. Everything would get shut down. And even the place where I was throwing Shock Value, until the last one I did a few months ago, got shut down by the police. Right now, there's a lot of on-the-books venues—like, there’s Nowhere and Elsewhere and Mood Ring and Bossa—and a lot of these places are really great and have really strong programming; they hire interesting people. But I do feel like to move all this culture that was essentially off-the-books to an on-the-books model—there's something that feels unresolved to me right now.

There's always something that’s lost when parties move away from the DIY.

I’m interested to see what happens. I don't think that’s a bad thing, it just feels unresolved. I think it would be amazing if clubs really started going in and giving artists budgets. Like, if you're going to do the on-the-books club culture thing, go all the way. That's my fantasy. I’m not saying that's what anyone has to do, but that's what I think would be an interesting outcome. A space that has a lot of money, instead of having a really big venue that is nice enough to do the thing and hire cute people, why not also do like video installations and change the stage once a month? I feel like there's just a lot of spaces that come off as a bit sterile. So, I have a hard time.

I’m glad that there's a Nightlife Mayor, though. I’m interested to see what she does. I mean, she—Ariel Palitz—she's the woman who gave me my first space, the first space I threw Shock Value, at Sutra Lounge on 1st and 1st. She owned it. So, that is encouraging to me. Just the fact that she let me, at 23-years-old, take over her venue every Thursday and trusted me—I think that’s a good sign.

Definitely.

I would like to see things get more after-hours. It’s happening more, but I’m over 4AM, or 5AM, as the cutoff time.

Me too.

That’s what sucks about the place I was throwing Shock Value, which was great. I mean, The Gateway was technically on-the-books—

But only a little bit.

Yeah, only a little bit. But that’s what I liked about it. I don’t wanna throw a party—I mean, if I have to, whatever—but I don’t want to throw a party at a super legit place, like, in the sense of ‘the walls are all clean, and the tiles are all new.’ That’s cool that all the bathrooms are already gender-neutral, but maybe it might also be cool if you have to put a sign on them saying so. I really loved The Gateway, and they got shut down by the police for some arbitrary fine and the owner couldn’t afford to pay it. And the two parties that were coming up next there were my party and Unter, which would’ve given them the money they needed. But it was in that short window that the fees spiraled and the owner was like, ‘I have to give up my lease.’

We were all really disappointed to lose that space off the J train, it was really unique.

I loved that space and I haven’t thrown a party since then. I am throwing Club Glow, my big party that I throw with Chris and DeSe, but that’s not Shock Value. That’s when I like doing an on-the-books venue. Like, if we’re gonna do the legit venue then let's do it, but I don't want, like, 200 person capacity and leave at 3AM. Why am I filling out a W-9 for a 200 person venue? I’m not doing that.

We’re living in a very turbulent time on an overall scale. What measures have you been taking to keep yourself in a strong emotional space?

I mean I do a lot of psychedelics. And I dance. That’s what I do—I dance. Specifically, one of the things I like about going to other places [outside of the U.S.], is that I don’t have to stop dancing. Dancing, to me, is really, really important. I don’t like going to the gym—I’m not a gym person. I’m not obsessively planned, and no crazy diets or whatever. I just wanna dance. I’m happy when I dance, my body looks good when I dance, I feel good when I dance—it’s just what I want. Think what you will or won’t about Berlin, I just like that I can dance for hours. I can dance for hours on a Tuesday night somewhere. If I wanna start at 4PM, if I wanna start at 5AM, it doesn’t matter. I wanna lose myself, I wanna take some mushrooms, I wanna dance for a set, then I wanna go to sleep. It’s good for my metal health, it’s good for my physical health and I’m finding that to be really difficult in New York. I’m leaving the house at 2AM. I’m not going to a party at 11PM, 12AM, and I only get four hours of dancing? What kind of culture is that? It just sucks. I always say to people like, ‘This is not the city that doesn’t sleep.’ I don’t know where people got that from. It’s more 24-hours in small-town America—at least Walmart is always open.

Do you have a selection of dance floors that are your favorite when you’re not behind the decks?

I’ll keep it New York specific: I love Unter—that’s a party where I know I can get some marathon dancing in. What else—really any place where I can get topless and no one's gonna be up in my face. I also love Bossa. It’s always there. They’ve been doing what they’ve been doing for a long time and I’ve had so many good nights on that dancefloor.

That’s a perfect top two. Like you said, our city is sort of in a place of creative growth and there’s a lot of room for new spots.

There’s lots of venues that I love playing at but when I go I don’t really dance, you know? Like there’s a big dance floor and I’m technically moving, but I’m not really going off. I’m going to parties and feeling like, ‘This is cute to chat but I’m not actually going off, no one is going off, no one is dancing.’ But I do really like Dreamhouse—Dreamhouse is cute, too.

I’m into it.

When I’m away in places where I dance a lot and come back people are like, ‘Oh you look so cute, you look so fit,’ and I’m like, ‘Yeah, it’s ‘cause I’ve actually, literally, just been dancing. Nothing else. Just dancing.’

But I also wish there were more festivals, a festival culture here. Sustain-Release was great. That would be cute.

Let’s talk about representation. Right now, the intersex, non-binary and trans communities are seeing an increased media representation with the premiere of shows like Pose and characters like Bex in Assassination Nation and Raven on MTV’s Faking It. While we obviously still have a long way to go in terms of constructive/beneficial narratives, have there been any strides in representation that you’re happy to see?

For me, it’s music. I don’t think visibility is an end goal—I don’t think visibility in and of itself is progress. In some ways, maybe, but I think music is probably the place where the most progress is present. My friend Ziúr—she makes amazing music. I love that there’s so many people who are making brilliant music, whether or not that kind of music directly vocalizes their experiences as trans or gender nonconforming people. I think that’s where I see the most people where I’m like, ‘Thank you for doing what you’re doing, I relate to this, this does something for me.’ And that includes the production side—the side of music that’s generally super super cis-male dominated. That’s where I see a lot of really exciting stuff happening.

I really like that you specified visibility as not being the end goal.

I think maybe that’s why I’m so attracted to music. Music has to carry a life of its own. To a certain degree I guess art does too, but I’m not really about the trans fashion moment. I’m kind of grossed out by the fashion trans thing because it doesn’t symbolize anything outside of the sheer value of what transness represents as a sign. It’s a placemark—a unit of cultural capital. In fashion, in certain ways, it’s the most arbitrary, shallow way of dealing with transness. Because there’s nothing else behind it. Music, on the other hand—your music can travel on its own. You either go ham or you don’t, you know? Like, I don’t care if someone's trans if their music sucks. Maybe there are people who are out here on that level but that’s just delusional and weird to me. I think that’s why I’m drawn to mediums and genres where, if there is visibility there, it acts as a catalyst for what’s actually coming, which is a conversation about music or a conversation about writing. I don’t get this culture of ‘I’m in a bunch of fashion campaigns therefore I’m an activist.’ I don’t really think that’s doing anything for most trans or gender-nonconforming people. And this is as someone who has done campaigns—I’ve gotten my coin but I’d really hate if that was all I was giving.

I first encountered your poem Untitled (For Stewart) on Tumblr during my undergrad years. Are there any artists who have stirred your interest through their digital presence?

I love Andrea Long Chu—@theorygurl is her Twitter handle. I’m obsessed with her and I’ve never met her in real life. I love her writing and the way she writes about gender. She’s a lit person with a focus in gender theory, which is kind of my background. That’s my academic area of obsession, so I love her work, I love her persona, I love what she’s doing.

You’re quite a young person and you’ve navigated your way to success in a number of communities that are often considered insular, like fine art, music, fashion and performance. What advice would you give to other women about finding their place in those worlds?

To me, the first step to anything is finding a way to generate an audience. Relying on other people to give you an audience, or the idea that other people will pay attention to you, or care about you, or circulate the things that you do, or whatever—assume that that’s not going to happen. You have to build all of that on your own—at least, that’s how I felt. That’s why things like Tumblr are important—because you can just generate your own audience. It didn’t matter that everyone going out thought that I was just some random person at a party because I was able to generate a space and dialogue that allowed me to feel like I had a place and a support system. Everything really grew from there. Having a group of friends also helps if you can grow things out from there. I used to do backup dancing for Adam and Antonio when they were performing as House of Ladosha. No one knew who I was or cared what I was doing, but that was a way for me to support my friends—I had their backs, they had my back, and then when I started doing stuff they supported me. I just assume that whatever audience I’m building, I’m gonna have to be responsible for building that myself. That’s a very ‘Southern Black People’ way of seeing things, but that’s how I see it.

That’s the same advice my mother gave me: be ready to build it yourself. Start that community yourself and have each others backs.

I also would say, whatever your lowest point is, think about that a lot. For me, my lowest point in my life was my childhood. So, whatever's happening, if it’s not childhood, it can’t be that bad. Some people find that kind of depressing and I’m like, ‘Well, keeping that in mind has gotten me through a lot,’ and I think it’s cute.

We’ve talked a lot about your successes. Have you ever been unsuccessful in an endeavor but learned or found growth from the experience?

All the time, yeah. I’ve done performances that everyone hated. In New York, there’s this thing where no one is going to tell you that they hate the thing that you do, they’re just not going to say anything about it. That’s what I’ve realized about New York. In some places people will be like, ‘I hate this, I think you’re an idiot’. But no one is going to say that in New York—radio silence is kind of the biggest read. And so I’ve done a ton of stuff that’s gotten total radio silence and it’s like, ‘Okay, learning my lesson from this.’

So, you take that feedback, even if it’s no feedback. You put that non-response through your filter of understanding and improve from there, right?

Yeah because I think growing from experiences like that requires you to humble yourself just a little. I know some people who are like, ‘Oh whatever, everyone’s just being a hater.’ And sometimes people are just being haters, but even within that circumstance where you feel like you’re being attacked or undervalued, or someone's not appreciating your thing, I just try to think of something that I can take something away from that.

You mentioned the release of some new music next year. Are there any other themes or new projects that you’re looking forward to exploring in the near future?

There definitely will be more. I have some things that I’m loosely working on, but this year has been a lot. I’m kind of ready to just, like, not have to think too much about what I’m going to do and just lock myself away during winter and work.

Juliana's next party, 'Doll Gang Massacre,' is at Queens' Knockdown Center on October 27. All photos courtesy of artist.