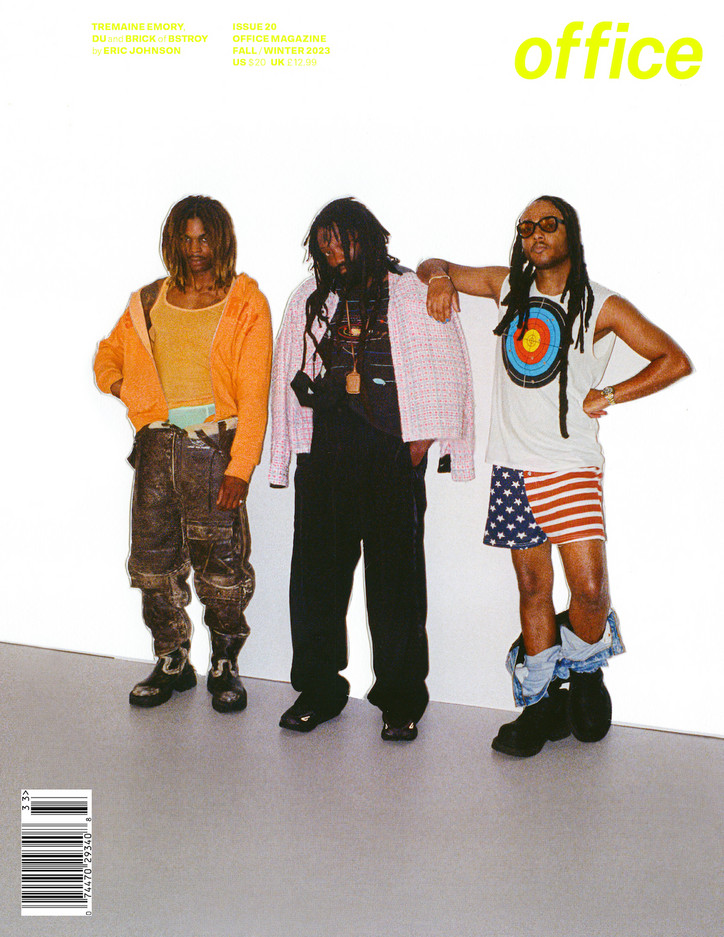

Keeping It In The Family: Tremaine Emory x Bstroy

Du tells me a story about one of the earliest launch events for the first collaboration between Nike and Off-White, when Tremaine was asked a question onstage: “He had the opportunity to highlight somebody that's already in the light, or somebody that's clouted, to sound like he's ‘in the know,’” Du says, putting up air quotes. “But he chose to be honest, and shout out somebody less spoken-for, from our community, our tribe … when I saw that, I was like, he's a real warrior.”

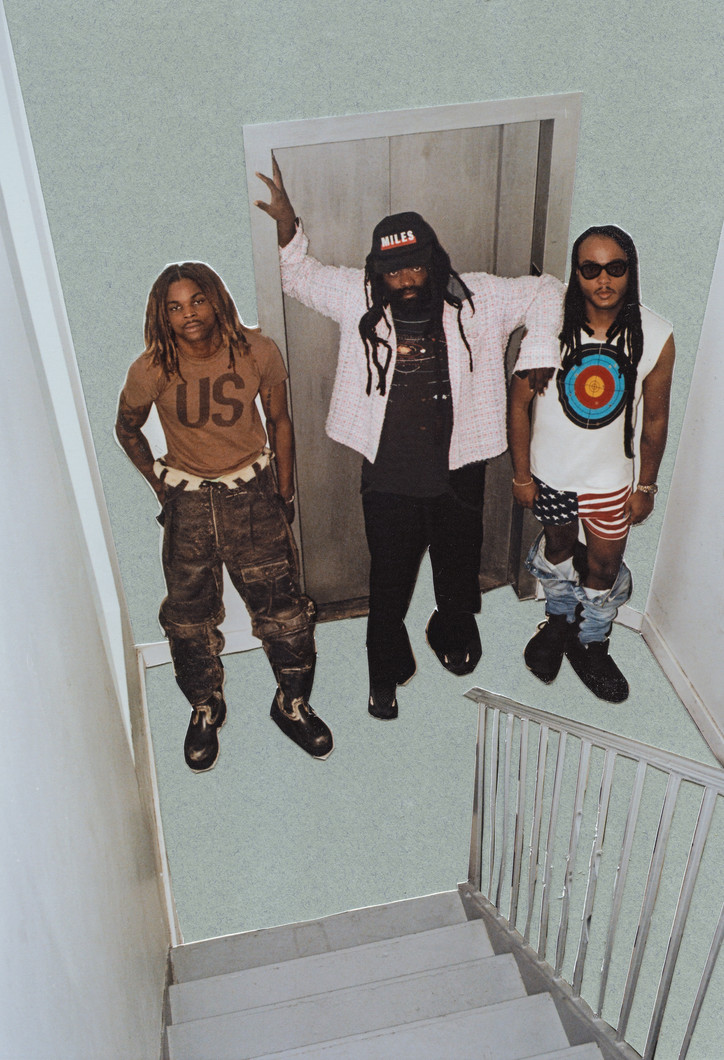

Born in Georgia and raised in Jamaica, Queens, Tremaine Emory’s career began with a retail job at Marc Jacobs in 2006, which eventually took him to London to manage a store location. It was there he would meet Ade “Acyde” Odunlami, with whom he founded the creative incubator and nightlife series No Vacancy Inn. He went on to art direct for Stüssy and consult for artists like Frank Ocean and Ye (formerly Kanye West). In 2019, he founded his own label called Denim Tears (a double entendre for shedding tears and ripping fabric) and in 2022, he was appointed the creative director of Supreme. His designs often reflect on the history of the African diaspora and the enduring legacy of slavery, frequently featuring hand-printed textiles and patchwork garments. Tremaine operates the same way in his speech as he does in his designs, weaving together comparisons, references, and connections between visual art, music, fashion, race, politics, and academia — and always, always seeking to reveal the bigger picture.

Atlanta, Georgia natives Brick Owens and Dieter “Du” Grams founded their label Bstroy in 2013, after befriending one another on MySpace. They held their first fashion show, called “Boys Don’t Cry,” at the Buckhead MARTA train station, without authorization from city officials. “There’s no fashion press in Atlanta,” Du explains. “So if you want anybody to talk about it, you have to do something that breaks the law. The first show we did made the local news.”

It was one of what Brick calls “eureka moments.” “Like oh, shit. It’s possible. If this works, we can do anything.” That combination of improbable self-assuredness and willingness to break the rules caught the attention of Givenchy men’s artistic director Matthew Williams, who invited them to Italy to work on his own brand Alyx, and Ye, who invited them to consult on his brand Yeezy. They’ve continued to design under Bstroy, unveiling often politically charged collections like their Justice capsule, which chronicles the list of departments that have personally antagonized the duo through garments with defaced police department logos. In fall of 2022, they released a capsule collection in collaboration with Givenchy.

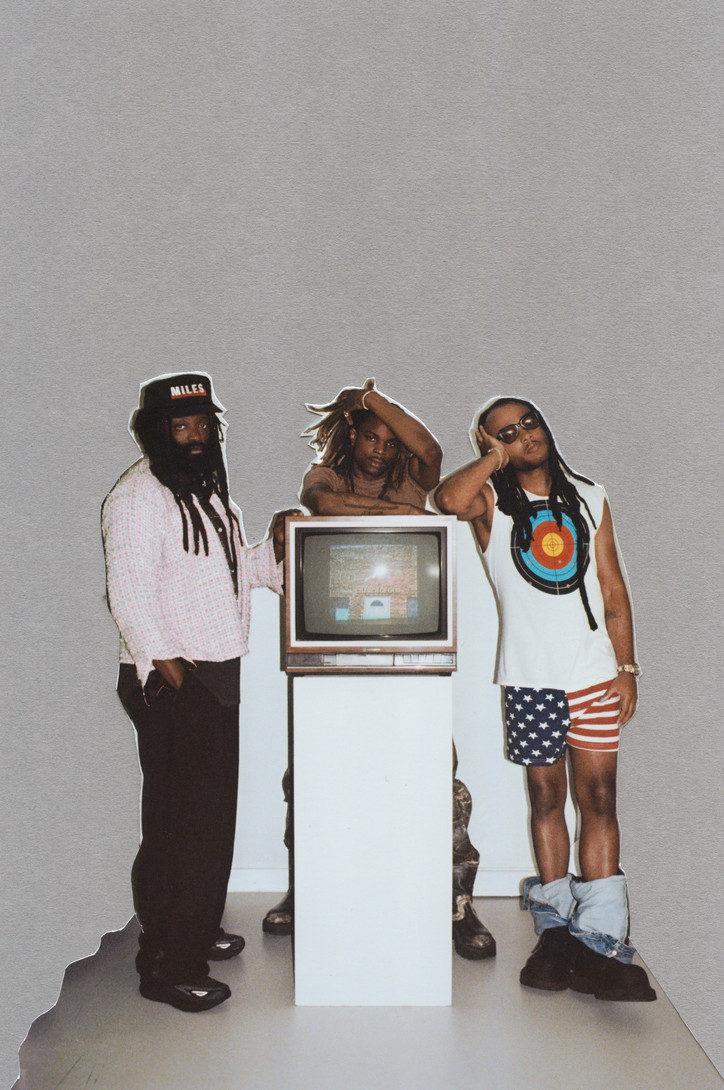

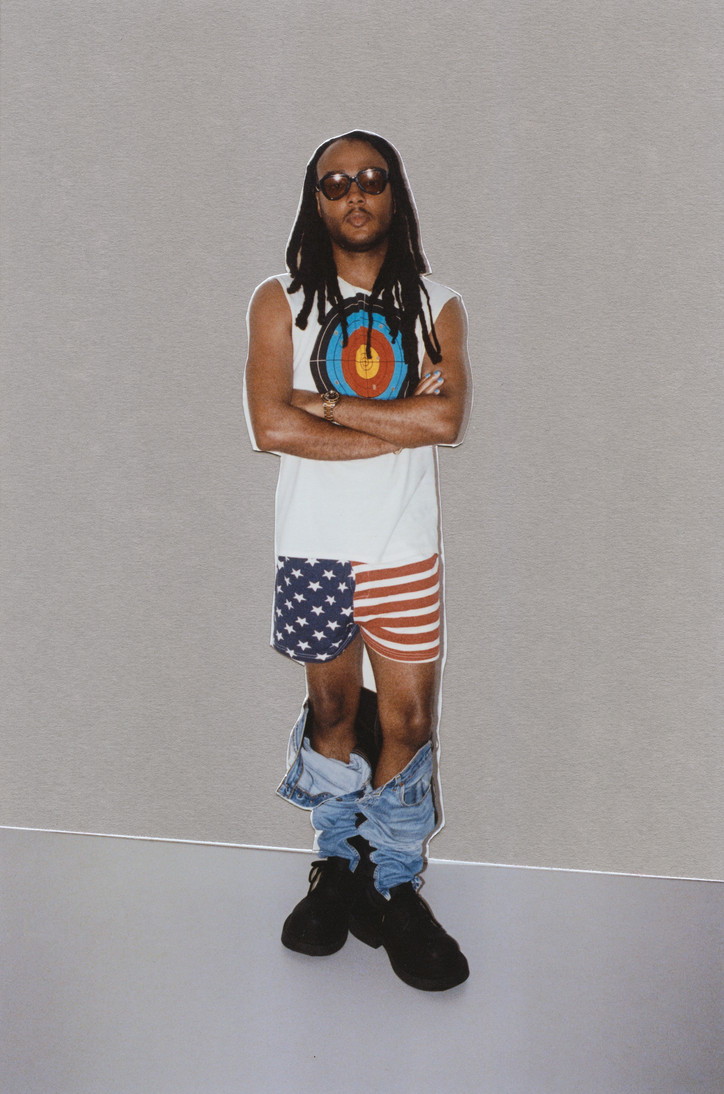

Brick and Du moved to New York in 2015 and eventually met Tremaine through mutual friends at the Mercer Hotel, the genesis of a bond that transcends the labels of friendship, mentorship, or collaboration. Throughout our conversation, the three lovingly challenge one another’s ideas as often as they finish one another’s sentences. They share a reverential, sometimes grave devotion to their work that defies the frivolity and self-indulgence typically attributed to the fashion world; words like “battle,” “mission,” “war,” and “superhero” are used liberally and unflinchingly.

Their access to fashion’s most coveted circles and collaborative opportunities at this stage of their careers does not come without its fair share of discordances. “It’s a fight,” says Du. “At every meeting, at every conversation, it’s a fight to contextualize yourself properly, because people want to trick you out of what's actually going on.”

Du’s words prove prescient; six weeks after our conversation, Tremaine is to announce his departure from Supreme on Instagram, citing his concerns with systemic racism within the company. Graphic images from an upcoming collaboration with artist Arthur Jafa reportedly caused internal disagreement within the company and were removed without directly informing Tremaine, who was dissatisfied with the results of his follow-up conversations with Supreme founder and owner James Jebbia.

“It’s a white, hetero-male dominated company and C-suite,” Tremaine says when I speak to him on the phone about a week after his resignation. “And so that permeates through all the decisions… and the perfect example of that is the lack of diversity in the design core, especially for a brand that is heavily influenced by Black culture.”

The images in question — one an infamous 1860s photo of the scarred back of a former slave, and the other depicting a lynching — sparked a controversial response from the fashion community and evoked a broader debate about the contextual suitability of using a brand like Supreme as the medium for sensitive messages about race. But Tremaine’s grievances are with the way the issue was handled, not with the removal of the specific photos.

Initially, Tremaine says he was told that the collaboration had been delayed so that he could appear in the promotional interview video with Arthur Jafa. “Even that is some white shit,” he says. “I interviewed Andre 3000 last year, and I'm not on the screen. You don't hear my voice, just like any other Supreme interviews… in my head, I'm like, ‘Y'all want me to be in front of the camera now?’ Oh, I get it.” Eventually, he was told the photos from the collaboration had been removed altogether.

“My issue with James is that he said to my face that we need to put this out, ‘because this is still happening to Black people,’” Tremaine recounts. “So if you change your mind, you damn sure need to talk to me about it. Just like you looked me in the eyes the first time, you gotta look me in the eyes and say, ‘We actually can't do this.’ I would have had questions, I would have had objections, but I would have accepted it and moved on. What I can't accept is that I'm the one Black person in the C-suite, and there’s five white people in the C-suite having these conversations about this project without me.”

According to Tremaine, the images were flagged by another Black employee who has also since resigned partially due to their own issues with their treatment within the company. He reads me some of the texts of support he has received from the few former and current Black employees at Supreme thanking him for speaking up. “I’m a Black person of a certain notoriety and degree of financial security,” Tremaine tells me. “Whereas [other employees] don’t have James Jebbia pulling up to their crib to talk for four hours after they resign.”

In our first conversation with Brick and Du, Tremaine is already sober to any illusions about the significance of his role. “Me becoming creative director of Supreme, I don't see that as progress at all,” he says. “When I go back to my hood and one out of four motherfuckers aren't in prison, then something's changed. I'm not a symbol of progress for Black people. I'm a symbol of progress for the Emorys. And even that — if I look at what I've achieved, and even within my family, what some of my family members are struggling with, I'm a one-off and I'm not better. I'm not smarter than nobody in my family.”

"‘How many Black people work at Denim Tears?’ Or, ‘How many Black people work at Supreme?’ I'm not saying those aren't valid questions,” he continues. “But how many Black people can get a loan? How many fucking Black doctors are there? How many Black people have …”

“... -the luxury to experiment?” Brick finishes his sentence.

“The Black life is still so much about survival,” says Du. “Most haven't had the opportunity to specialize and live off art in a professional way. I will say, V did an excellent job of employing people of color, and equating their experience to an artistic education, making sure they’re valued even if they don’t have a certificate from a school.”

He is, of course, referring to the late Virgil Abloh, founder of the label Off-White and the first Black creative director of Louis Vuitton. An early supporter of Denim Tears, No Vacancy Inn, and Bstroy, Virgil was a beacon of professional and personal guidance and inspiration. The three men bring up “V” affectionately and often — citing his work ethic, his compassion, his humility, and his strategic wisdom.

Tremaine learned of Abloh’s passing from a New York Times push notification the same week he received the offer to become creative director at Supreme. “I landed in Miami and had 200 messages, everyone saying ‘sorry for your loss.’ The only pop-up I have on my phone is the Times, and then it popped up, that Virgil passed,” he describes.

Brick recalls how he delivered the news to Du, who was visiting his family in Atlanta: “I remember you pulled the car over on FaceTime, the way you just said, no.”

“I almost crashed the car,” Du says. “You don’t ever think your superhero is gonna die. From that day I left Atlanta and I was like, ‘I'm not taking no breaks.’ Because V was somebody that, you call him at any moment, he’s picking up the phone for you, but he's knee-deep in five things, and he'll show you. We only get 24 hours in a day, but it seemed like he had more.”

That refrain — I’m not taking no breaks — gives me pause. When I ask about work-life balance, the three exchange sly smiles. “When I talk about this tribe and this mission that we’re on,” Du says, “It’s really our whole life. I think that’s the only reason why we see anything back from it.”

Tremaine references Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks, in which the French psychoanalyst and philosopher expands on the “double consciousness” Black people experience as a result of viewing themselves through the eyes of a racist white society. “That shit is ingrained in everything, and you have to work against it,” Tremaine explains. He tells me about his uncle, who was never once late to work in 40 years at the same job. “He knew he couldn’t be late because he’s Black. We can’t take six weeks off in the summer holidays like they do in Europe and turn off our emails for August. That shit doesn’t work for us, man.”

“It’s funny, people say to me, ‘Do you think you got the aneurysm because you work so hard?’” Tremaine continues. “And for one, no I didn’t — they’re hereditary. But even if it was the cause, I wouldn’t change a fucking thing because I wouldn’t have been able to make it this far if I didn’t work how I worked. Being mediocre isn’t allowed for Black people, and part of that is working all the time. It’s unfortunate, but that’s the truth.”

The lower aorta aneurysm Tremaine is referring to occurred in October 2022, just 8 months after he took the helm at Supreme. It left him hospitalized until the end of the year and forced him to slow his pace for perhaps the first time since his career began, but Tremaine’s idea of deceleration looks a little different. Even as he was still hospitalized and engaged in physical therapy to regain his ability to walk, his “Dior Tears'' capsule in collaboration with Dior Mens was unveiled in early December. He credits his survival to the support of his friends and loved ones. “What saved me was the love of my fiancée Andee, of Acyde, Anthony [Specter], Cactus [Plant Flea Market founder Cynthia Lu] flying in from Hawaii twice, Brick and Du bringing me books.”

“I remember one time I had to stand up for five minutes without a walker, which was really hard,” Tremaine tells me. “And then Brick took the time to make me do like eight minutes, or 10 minutes instead of five minutes. All those things in my life where someone has pushed me and seen what I can do — I didn't know I could stand for eight minutes, but Brick felt that. That’s the best kind of help, when people believe in you and push you to do what you don't know you can do.”

Brick looks almost surprised. “Me pushing Tremaine — at that moment when I did that, I just saw something that he didn't see for himself,” he says. “At many times, Du was that person to me. The inner workings of those relationships are so interesting.”

“But also, if you're friends with a superhero and you are present during their recovery, you're gonna push them a little bit because the world still needs to be saved,” Du adds. “I feel like the job is that serious for us.”

The hyperbole may be extreme, but its extremity seems more warranted when you consider the dearth of the three men’s comparable living contemporaries. According to a 2020 report from Women’s Wear Daily, Black members only make up 4% of the Council of Fashion Designers of America. Tremaine tells me about how he was recently mistaken for a homeless person in his TriBeCa neighborhood, and still gets racially profiled in public spaces—including at a bakery the day his position at Supreme was announced. The dissonance between the discrimination and the highly visible success these designers have experienced is only exacerbated by the isolation they experience in their field.

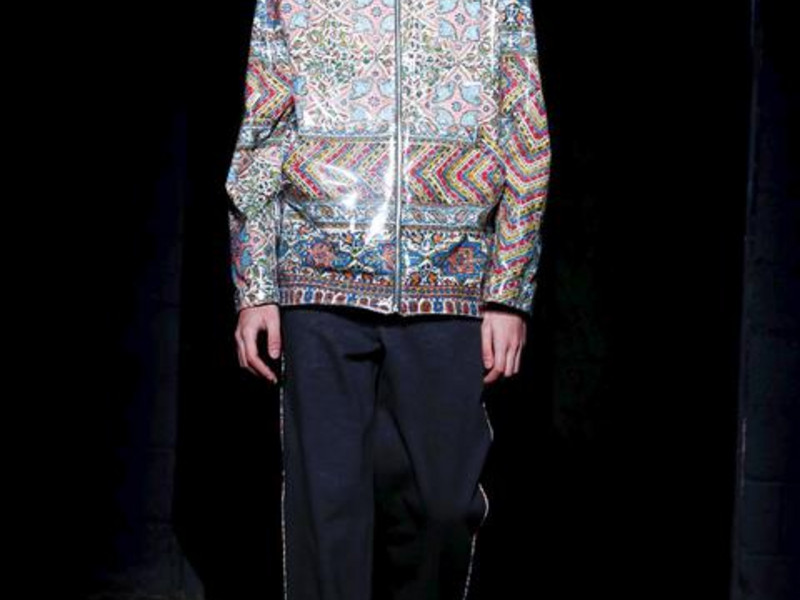

“When you break through as a Black person, you're usually alone,” Tremaine says. That’s precisely why the inclusion of his designs among a collection of established legacy designers in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, alongside those of Bstroy, Hood By Air (Shayne Oliver), Fear of God (Jerry Lorenzo), Pyer Moss (Kerby Jean Raymond), Virgil Abloh, and Heron Preston, was so meaningful. The exhibition In America: A Lexicon of Fashion was curated by Andrew Bolton for the Met’s Anna Wintour Costume Center in September 2021 and added over 70 new ensembles in March 2022.

Tremaine confesses that he became emotional when the collection was unveiled. “I was literally waterworks crying when I seen it, and it wasn’t the validation of the Met solely. It was the fact that I was in there with my contemporaries,” he explains. “Even the designs included that I don’t fuck with, I still respected it. And it didn't say shit about ‘streetwear,’ it said exactly what the cotton wreath means, exactly what that double-headed hoodie means, and what that pan-African flag means.”

The diversity of that collection came as a surprise to some, considering the Met’s costume holdings are overwhelmingly white. As New York Times fashion critic Vanessa Friedman pointed out, the Met has “a pointed, fairly chunky political agenda of its own that has to do with redressing historical racism.” But irrespective of motive, the institutional canonization of Black designers as part of American fashion history is politically significant and in many ways unprecedented, especially for those who were previously relegated to the often dismissive label of “streetwear.”

Streetwear is largely thought to have originated in the New York City hip hop scene of the 1970s and 1980s, describing a style of dress that features comfortable, casual, and often looser garments like t-shirts, hoodies, workwear, sportswear, and sneakers with influences from Japanese street fashion, punk and skater subcultures, and status-symbol designer brands. The style was proliferated by rappers and musicians in the 1990s and early 2000s, and experienced a massive boom in popularity in the 2010s, heralded by many of the designers Tremaine mentions who were featured in the Met alongside him.

The 2010s revival brought about the cultural phenomenon of the “hypebeast.” The term, dripping with mockery, refers to an archetype of consumer that obsesses over the latest, most hyped streetwear products and seeks to flaunt rare and expensive garments and sneakers as status symbols. The hypebeast has become increasingly unpopular over time, drawing the derision of both the more pretentious and purportedly chic fashion class — to whom hypebeast culture is gauche, unsophisticated, firmly adolescent, and implicitly, too Black — and the normie crowd, to whom the hypebeast is materialistic, shallow, and tacky.

With streetwear’s spike in popularity came a conundrum of classification. Fashion gatekeepers were and often still are adamant on its distinction from high fashion, but designers like Virgil – who began his career screen printing t-shirts – increasingly blurred that distinction, designing haute couture at the time of his death. I am reminded of the history of another rule-breaking genre pioneered by Black people within a larger medium: jazz, which was coincidentally also one of the inspirations behind the Dior Tears capsule. Despite being one of the earliest original American art forms, jazz was punished for its amorphousness and condemned as a “primitive” and “immoral” form of music for decades before its eventual acceptance. But unlike jazz, streetwear’s title has yet to transcend its scarlet letter, and still carries a host of connotations. The insistent use of the term to describe designers that have long expanded beyond it often feels like a pointedly enforced division.

“I feel when someone says I'm a streetwear designer, you might as well be calling me a n*****,” Tremaine says. “Hard r.” Brick and Du nod in agreement. “I’m not knocking anyone who appreciates the term. But for me, anything that’s separation is derogatory. I'm not into the separation of anything when it comes to the arts.”

“Like, don't play with me. It's a matter of respect,” Brick adds. “For me personally, until we can get a textbook definition of what ‘streetwear’ is, I would prefer that we not be labeled as that. We're not sold in DTLR where we bought a lot of our shoes as a kid in the middle of the mall.”

“The thing is like, what makes it ‘street’?” Du asks. “Because ready-to-wear clothes are literally worn on the street. So what makes those streets different than the streets where people wear ‘streetwear?’”

“It’s all cement,” Brick muses.

“It’s a code word,” Du continues. “And it’s so obvious to us that it’s offensive.”

Tremaine references Fendi and Dior artistic director and longtime friend and collaborator Kim Jones, who told HighSnobiety in 2018 that he felt the term “streetwear” had outlived its descriptive use. “I currently design ready-to-wear and sportswear for men, and accessories,” Tremaine says. “That’s it. So I just wanna be called a fucking fashion designer.” I suggest another parallel: the former Grammy category of “Best Urban Contemporary Album” — once declared a “politically correct way to say the n-word” by Tyler, the Creator — which was heavily criticized for its generalization of work by Black musicians until it was renamed in 2020.

“What the fuck is that!?” Brick says. “It’s like ‘streetwear’. What does that mean besides, ‘Black, but we don’t want to say that.’”

“It's called segregation, and it was outlawed,” Du says, laughing.

Later in our conversation, Tremaine cites How To See a Work of Art in Total Darkness, a book by art historian Darby English that interrogates the interpretative limitations imposed on work by Black artists by perpetually centering the cultural obligation to represent Blackness, through an analysis of the work of contemporary artists Kara Walker, Fred Wilson, Isaac Julien, William Pope.L, and Glenn Ligon. “While limiting our attention to what these artists have to say about Blackness will surely ‘keep the conversation going,’” English writes, “it will also prevent the conversation from going anywhere particularly new.” Echoing Du’s language, English refers to “Black representational space” as functionally a form of “tactical segregation.”

“You can make something totally abstract that has none of these touch points of what is deemed to be Black. White people don't have to do that!” Tremaine exclaims. “No one's like, ‘Yo, you white photographer, you only gotta shoot poor provincial white folk in the Midwest.’ They could shoot whoever the fuck they want!”

“It's disrespectful, and it's just a way of condescending and boxing you in,” Du chimes in. “Because all of the Black people from history that did great things, the kings, the mathematicians, the inventors, they had to get off the fact that they were Black to do great things. It doesn't mean that they wanted to be any less Black. But the subject at hand wasn't themselves. You have to focus on other things.”

“I think when people have that wool over their eyes about color, and they hyperfocus on it,” Du continues, “It feels inhumane sometimes … It's like turning yourself into a zoo, a circus act.” The ideological narcissism that he identifies is the catch-22 of art in the age of neoliberal identity politics; if race is the sole foundation or interpretive focus of a work, then race will preclude any rigorous or dignified engagement with the work beyond its representational value.

Or as Darby English puts it: Black art is “almost uniformly generalized, endlessly summoned to prove its representativeness (or defend its lack of same) and contracted to show-and-tell on behalf of an abstract and unchanging ‘culture of origin.’” Even as they resist it within their creative endeavors, that unsolicited mantle of representative responsibility is inextricable from the profound sense of duty to their work that the three men have expressed.

But that sense of duty hasn’t yet infected Tremaine’s self-perception. “Supreme, Denim Tears, being in the Met or on magazine covers, none of that defines me. If it does, then I’m fucked. Because that’s all shit that can be taken away,” he says. “What defines me is how much humanity and compassion I got in me, my love for myself and for people and for my family.” That groundedness is perhaps the only antidote to the emotionally distortive pressures of his career.

To close our conversation, I ask about what the designers are looking forward to next in their careers and in the world of fashion. “I’m just grateful to be in the league,” Tremaine says. “Some seasons you’re gonna win a championship. Some seasons you’re not. I just look forward to playing more games.”

“I’m excited about working with more people that are equally as curious as us,” Brick says. “My favorite moments in work are the eureka moments of stumbling across somebody that knows something you’ve been looking for, that’s willing to share.”

“We just have to make sure art is always the main focus,” Du says. “Everything that we do has to be traced back to art.”

“You know what I’m excited about?” Tremaine muses. He references the Lupe Fiasco song “All Black Everything,” which imagines an alternate universe free of anti-Blackness. “I hope I live long enough to see the day where I can see a plethora of Black people doing all kinds of things, and it’s not a big deal. Like, if you watch an NBA game and you see a Black guy dunk …”

“You’re just like, all these niggas do that,” Brick laughs.

“That’s all I want in fashion,” Tremaine says. “And then when Vince Carter came in and put his arm in the hoop, that’s when you said, ‘Wow’. He took it further. That’s what I want.”