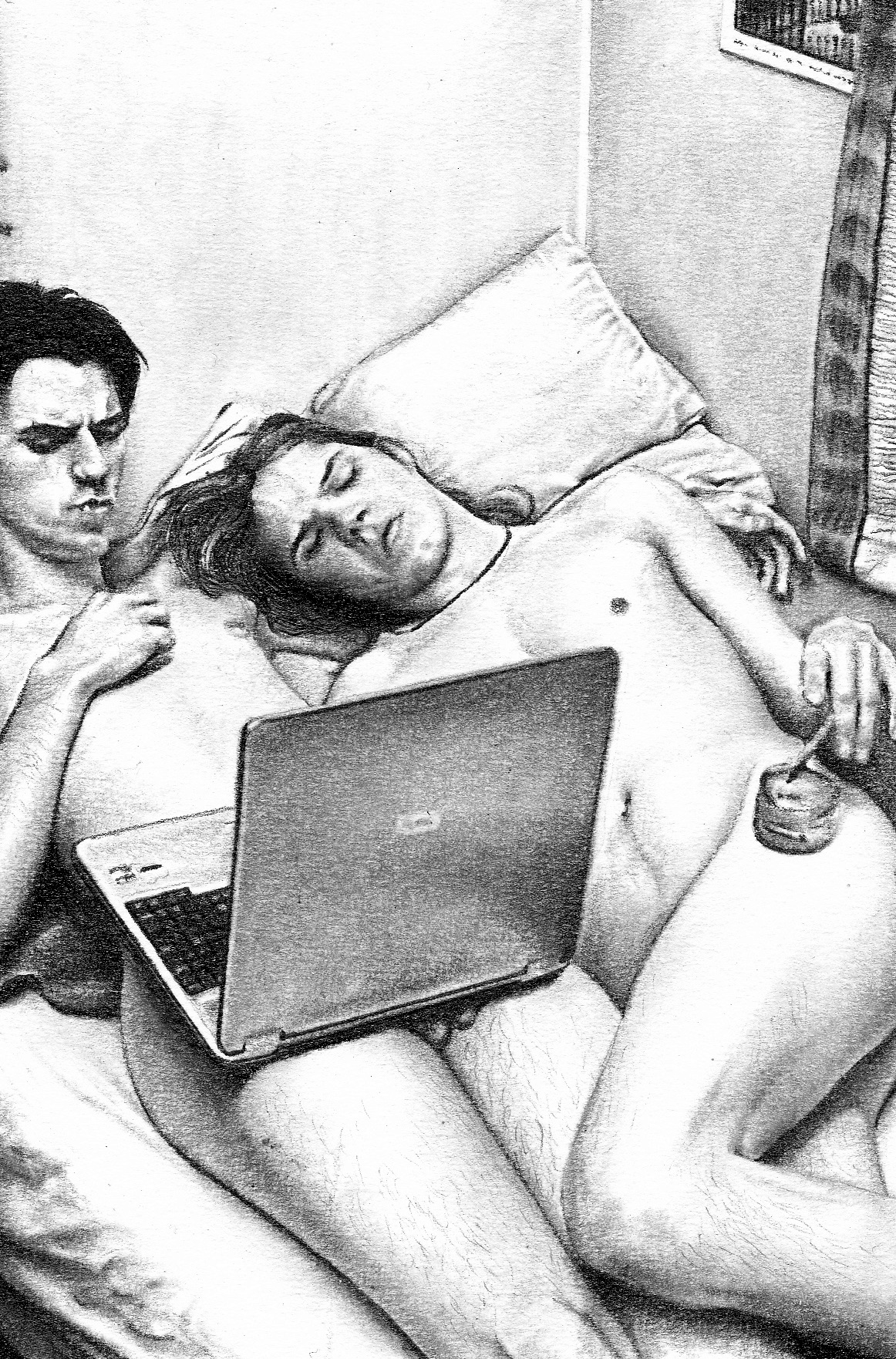

Samuel Ross in White Cube London

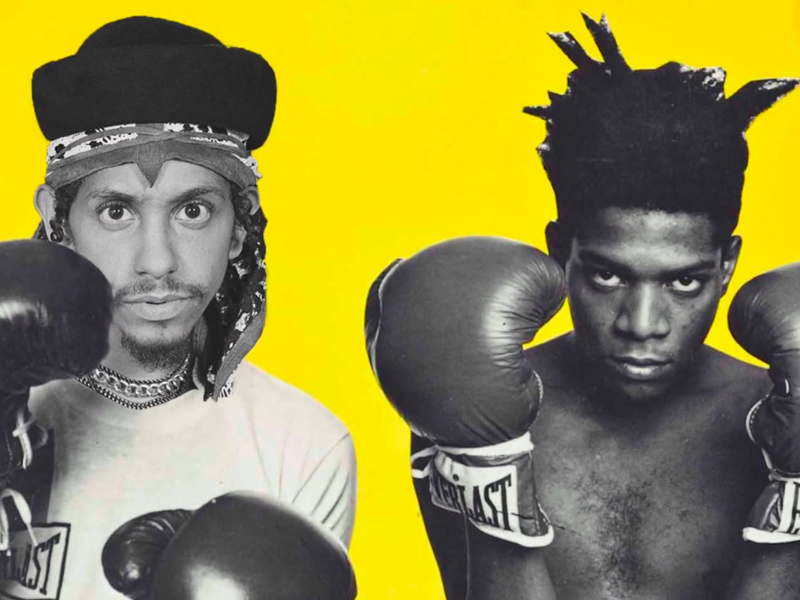

Samuel Ross has had a multi-disciplinary approach since his time studying graphic design and illustration at De Montfort University, Leicester. His accolades—and there are a lot—are one thing, but he does more than receive prizes. His self-funded label A-COLD-WALL* was established in 2015 (and a womenswear line in 2018), but he began in fashion with 2wnt4 (a streetwear brand made in collaboration with Ace Harper), and this led to his discovery by the late Virgil Abloh in 2013. Ross also formed Concrete Objects (in 2017) with Joe Burns and SR_A (in 2019), which focused on furniture design and industrial design, and scattered some watch design within that. His brands have thrived, but his artistic vision has been the translator across his trades. A-COLD-WALL* was inspired by Ross’ upbringing (and the British class system) and comments on societal inequality. At the same time, SR_A (as his design studio) has architectural takes on furniture that signify something more significant than their material—they send messages through mediums.

On Tuesday, ‘LAND’ extended that message.

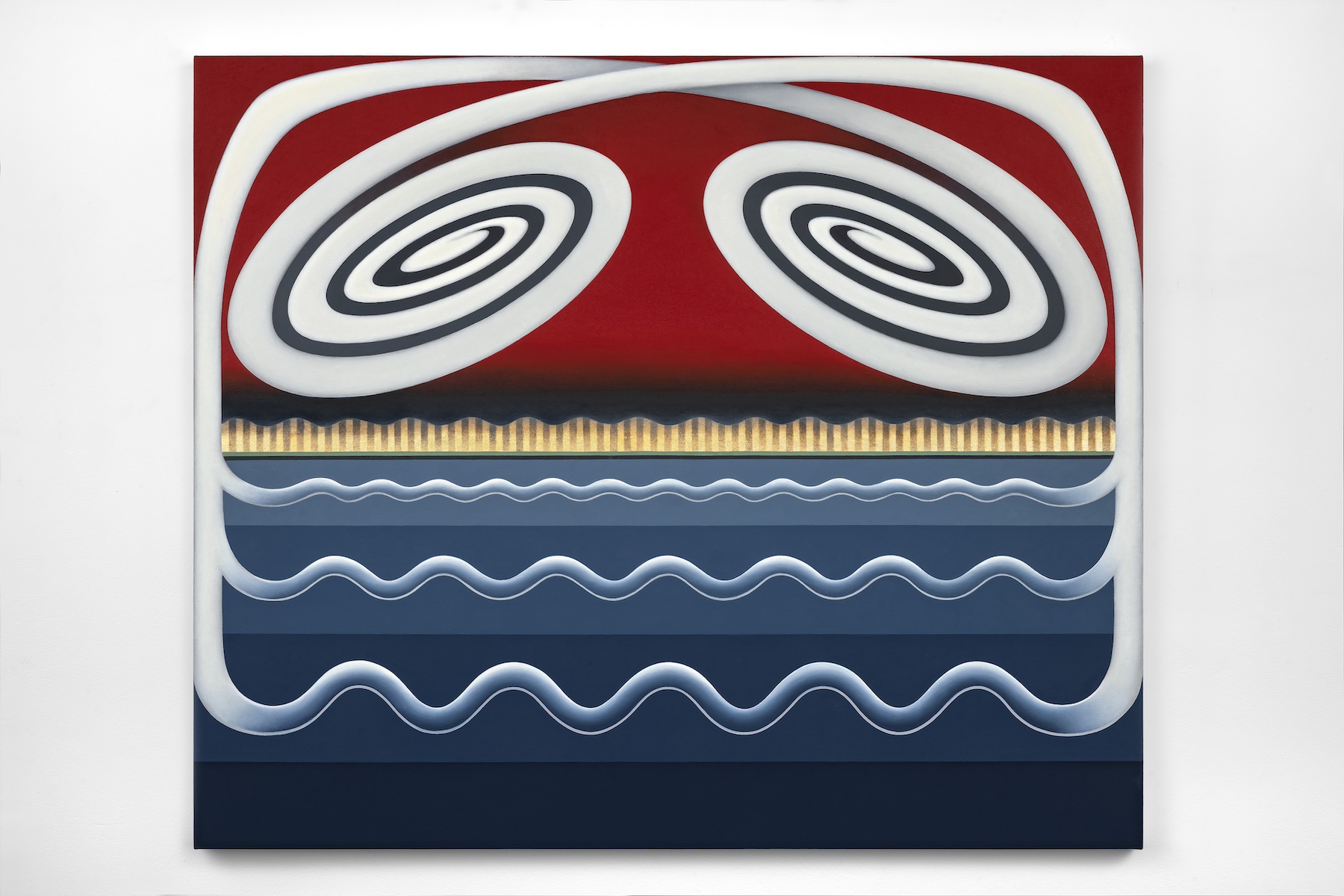

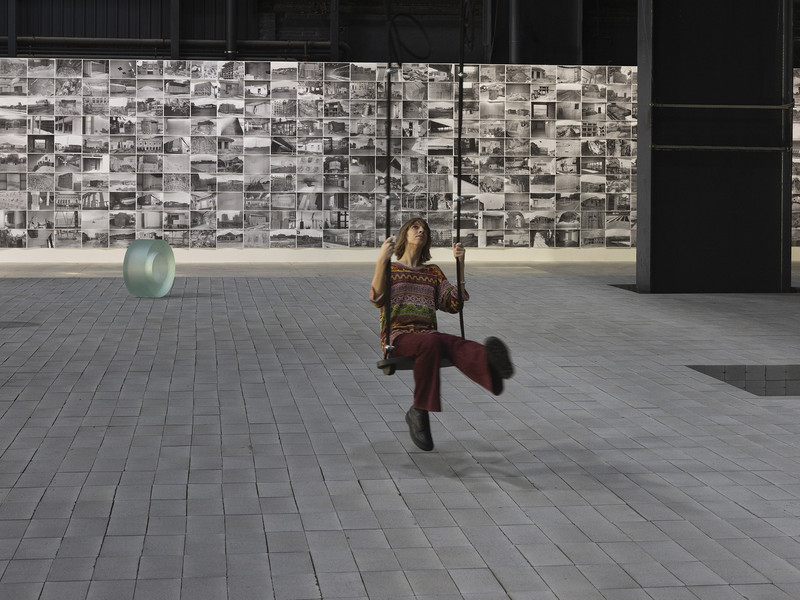

An industrial sentimentality hung from the walls and sat over the polished concrete floors of White Cube’s Bermondsey gallery. The message was open to interpretation, unconstricted, informative and discursive. Very Ross. Unlike the fast-paced and gruelling world of fashion, where the need to produce seasonal collections takes priority, these paintings were made over a year. Reminiscent of Richard Serra’s ‘let the work speak for itself’ mentality, the pieces were crafted over time—some of the larger works took up to 11 months—with industrial materials layered, scraped, swathed, and scratched.

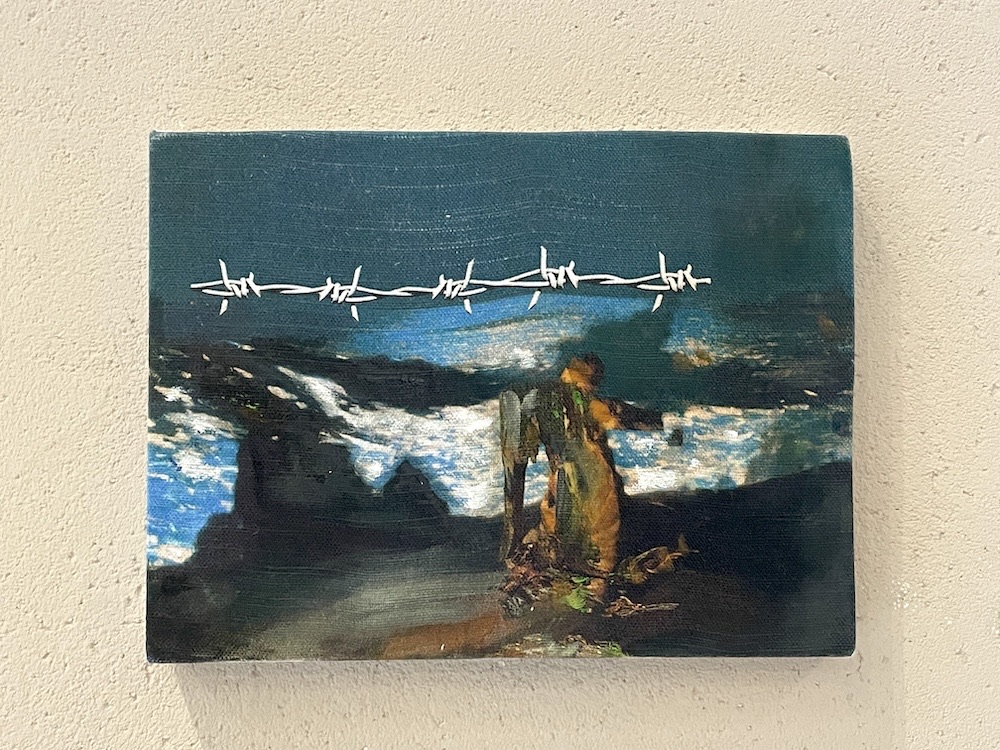

Held in floating steel frames, the paintings reflect an emotive Samuel Ross, one held on a wall rather than worn with a tick or tucked into pants. These paintings are emotional. In contrasting blocked-out spaces (similar to Nicolas de Staël and his use of a composition as a perspectival device), Ross expands upon the ‘Black experience’ by exploring industrial materials and dislocated landscapes seen from above. Somewhat derived from old blueprints, their content echoes information, and the geographical references are implicit. Here, pigment is political. It communicates images: rust colours the mind into a picture of a factory, and a black-wreathed painting is as heavy as a welding desk. There is something to be seen behind the laborious work and meaty textures depicted.

OTHERS SEE IT (2022) is the darkest of the dozen. Painted over OSB board (made from compressed layers of wood strands), dollops of cracked, opaque emulsion and acrylic protrude alongside blackened aluminium tape and soaked card, their folds pressed like a pocketed origami. The refracting sheen of the acrylic and the light spray of metallic aerosol balanced the overwhelmingly dark painting that could easily dampen a room. Etched-over emulsions are mixed with masonry paint to form an intense craquelure rivalled only by the feeling of dry skin. They look ashy, and the paint appears to have dried like tar or igneous obsidian lava.

CLOSER TO DISSONANCE (2022) is a packed image. It absorbs a collection of mediums over soaked duck canvas. The colours of sand and honey mingle with speckled rust, parakeet green, and brushed eggshell and slate. A thin filament of light spreads across the boards like a Morandi backdrop with no bottles. The composition is less considered than, for instance, Robert Rymans’ To Gertrud Mellon (1958), which has a similar palette and a more restrained application of paint. The work hangs beside two other paintings. It appears sensitive, timid and unwilling to depart from its siblings. The expressive application of paint makes the works sit at ease in the apparent series, creating a wholeness that can only be felt when stepping back and observing all three works at once.

However, ANEW (2022) is heavily worked. It has implications of a topography seen from above. The honey-soaked card plays across the wood panels like glue on a draftsman’s table. The materials spread across bordered boards, displacing the panels in an allusion to broken geographical boundaries and overlapped space. The vincular cracked paint, and its similarities to shino-yu (allowing the surface glaze of ceramic to break), is potent, referential and intentional. Conservators have struggled with artworks by Willem de Kooning, Francis Bacon and Jackson Pollock thanks to decomposing and cracking house paints. Ross places this industrial material in its barebones reality. As damaged. As imperfect.

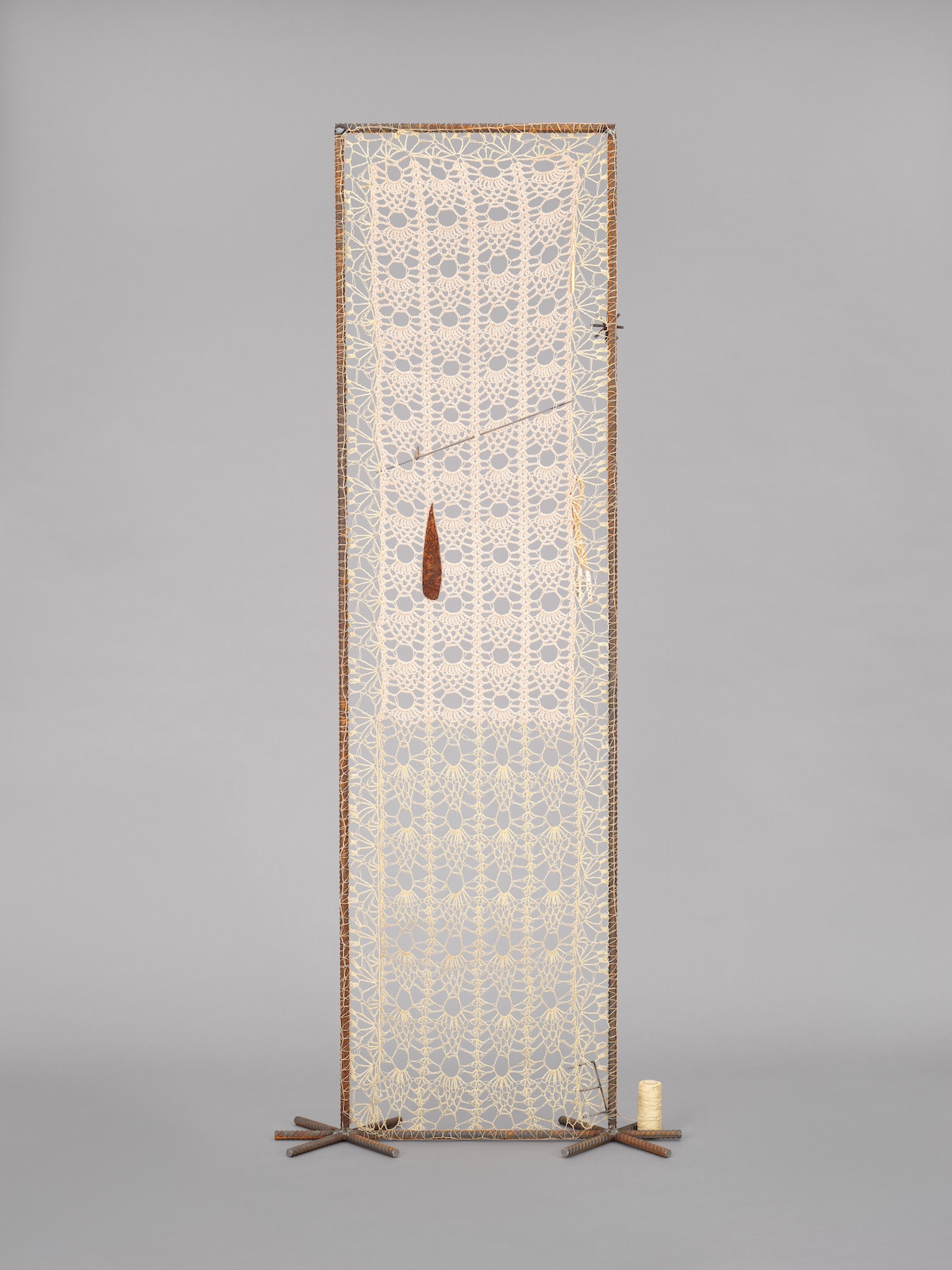

The exhibition featured not only paintings but sculptures: three of them. Made from powder-coated steel and aluminium, their presence crowded the space in the middle of the room, separating the painted works into oblique sections. Rather than muting the experience, the sculptures sat humbly on the floor like cuts in the stencils of Alexander Calder’s dials. The larger steel and aluminium bodies were derived from sketches, while the smaller works, such as DISTANCE COLLAPSE IN HEARTLAND (2022), were forged from found materials. 7 HOURS (2022) had pressed pigments of Indian dye that diluted the canvas, sparking an immersive experience with the surface. However, the sculptures merely added to the sensory environment. They somewhat placate the intensity of the paintings, but not much more than the concrete block attached to the burning incense sticks and the ambient soundscape that can be heard in the room. Whereas the paintings shared frames like bread and wine, sculptures such as BODY WITH LAND (2022) added scale and shared the space, but at the cost of padding an already full room.

The paintings were self-conscious but content, and there will always be deliberation in the uneven crust of interpretation. Nonetheless, the images speak for themselves in a clothed way. Their compositional portrayal and the impasto cracks, bulges, and creased canvas all add to the feeling of a rising chest and breathing being. A being with a history and pain. The unspontaneous voulu in the sculptures is forgivable. The paintings are the purpose of the show. They are the heavy movers, the forms that assuage. They performed Ross’ expressive energy and gave a perspective with a whisper of emotion that, with breaths and a gaze, can make one think.

What about? Ross leaves that up to you. But one thing is for sure. The story of Samuel Ross is not over, and he’ll be back — in some way or another.