Mysterious photographer Martin Kollar on his new book, 'Provisional Arrangement'

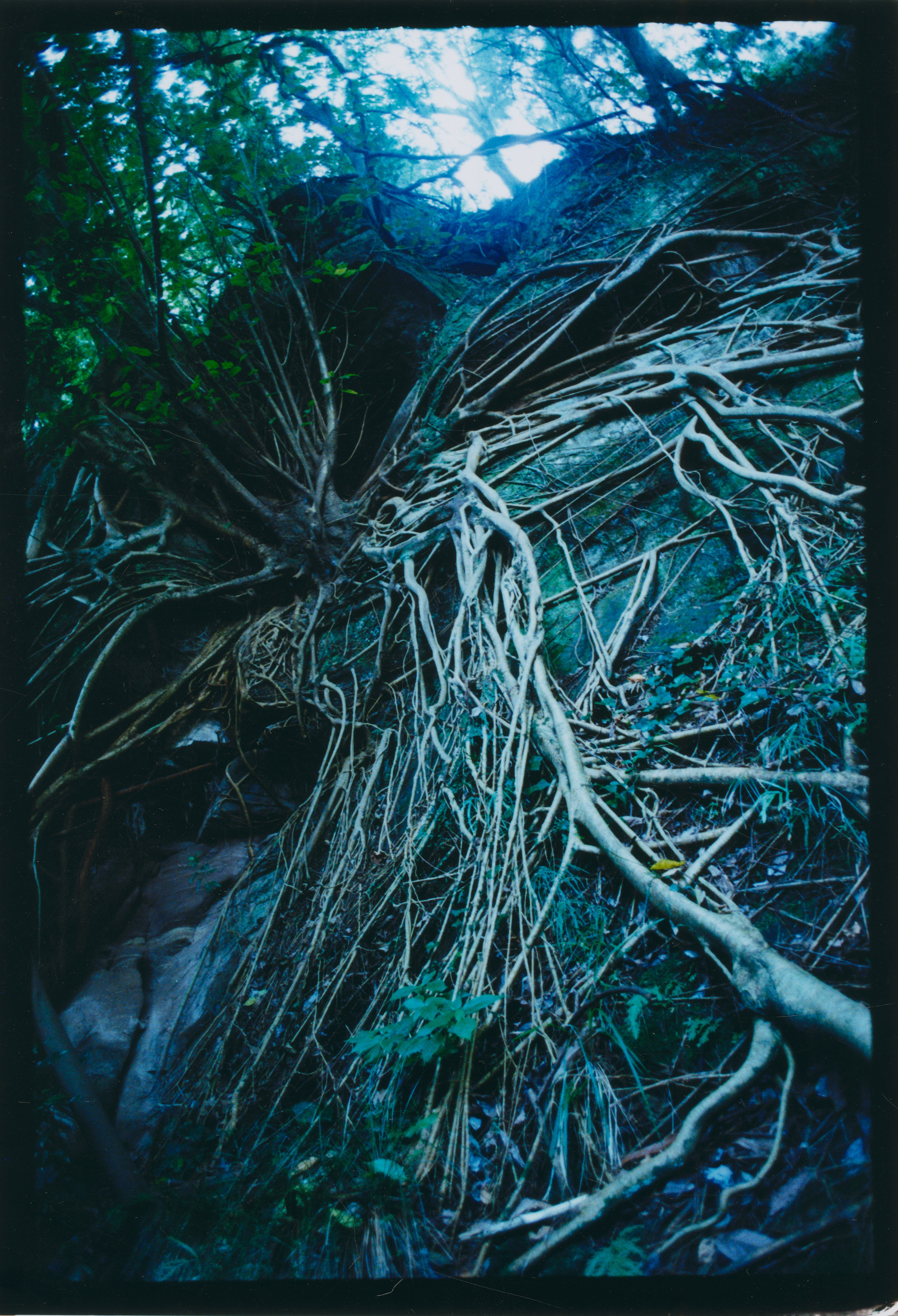

Czech photographer Martin Kollar's pictures can evoke a similar indescribable sensation. They often capture nondescript locations that feel at once familiar and alien. The haunting and surreal images instill a longing to know more, an itching urge to know the backstory, get the insider’s perspective. Like kaukokaipuu, the bizarre feeling that Kollar’s photographs elicit falls somewhere between wanderlust and a sense of lingering déjà vu.

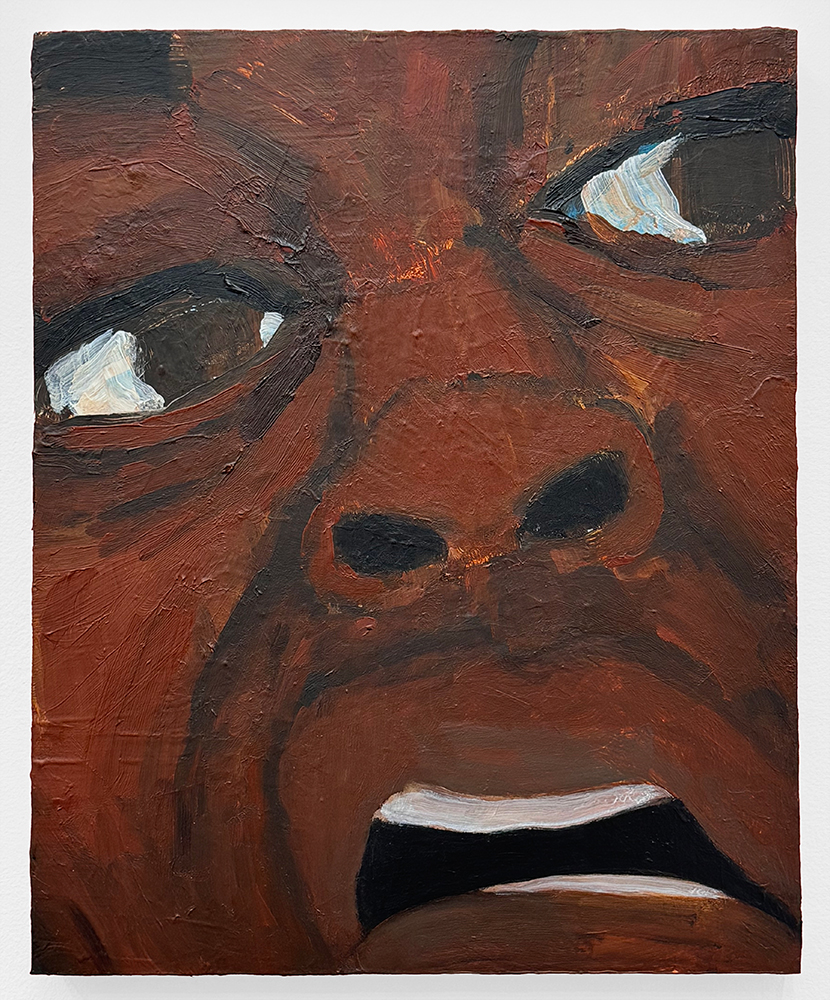

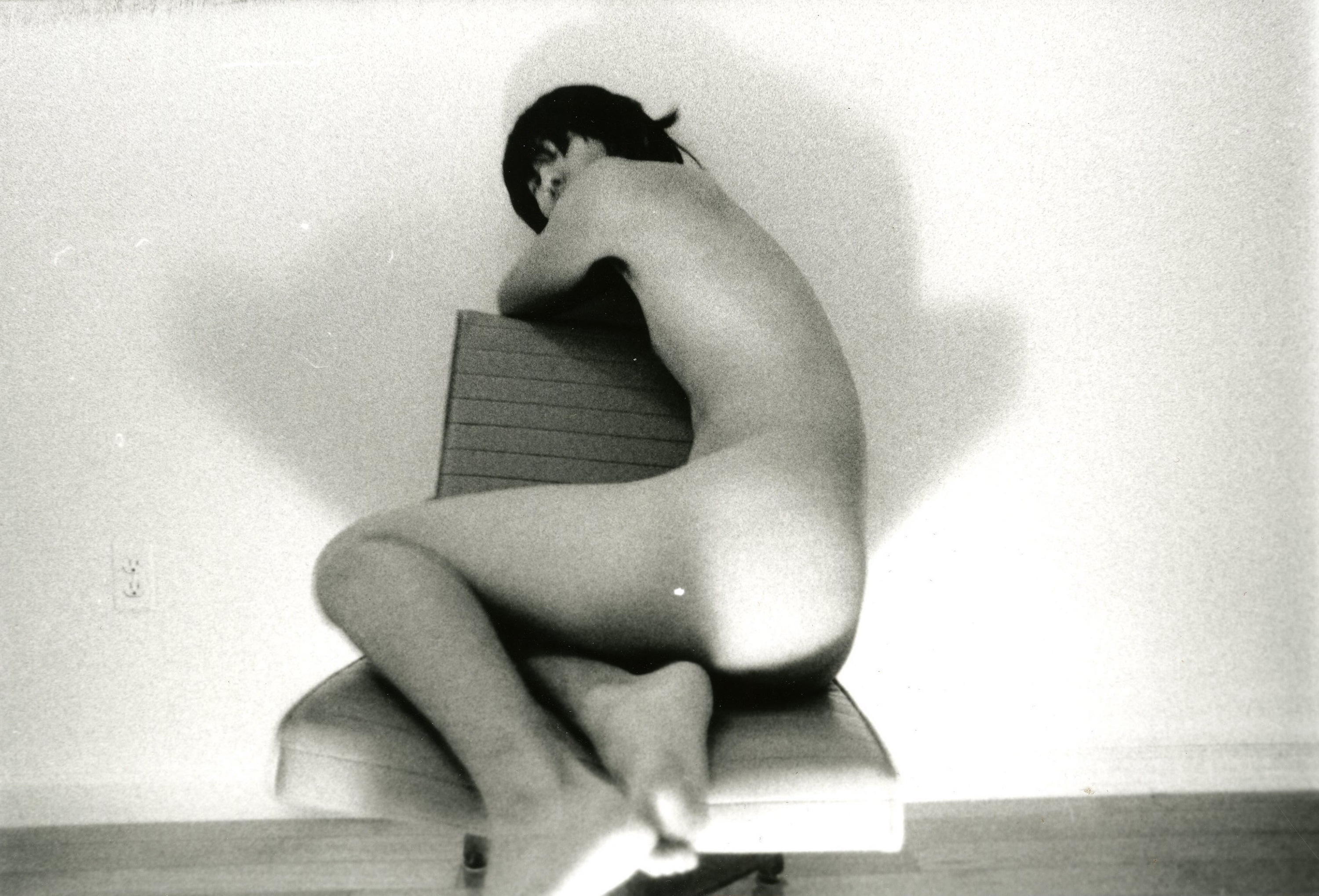

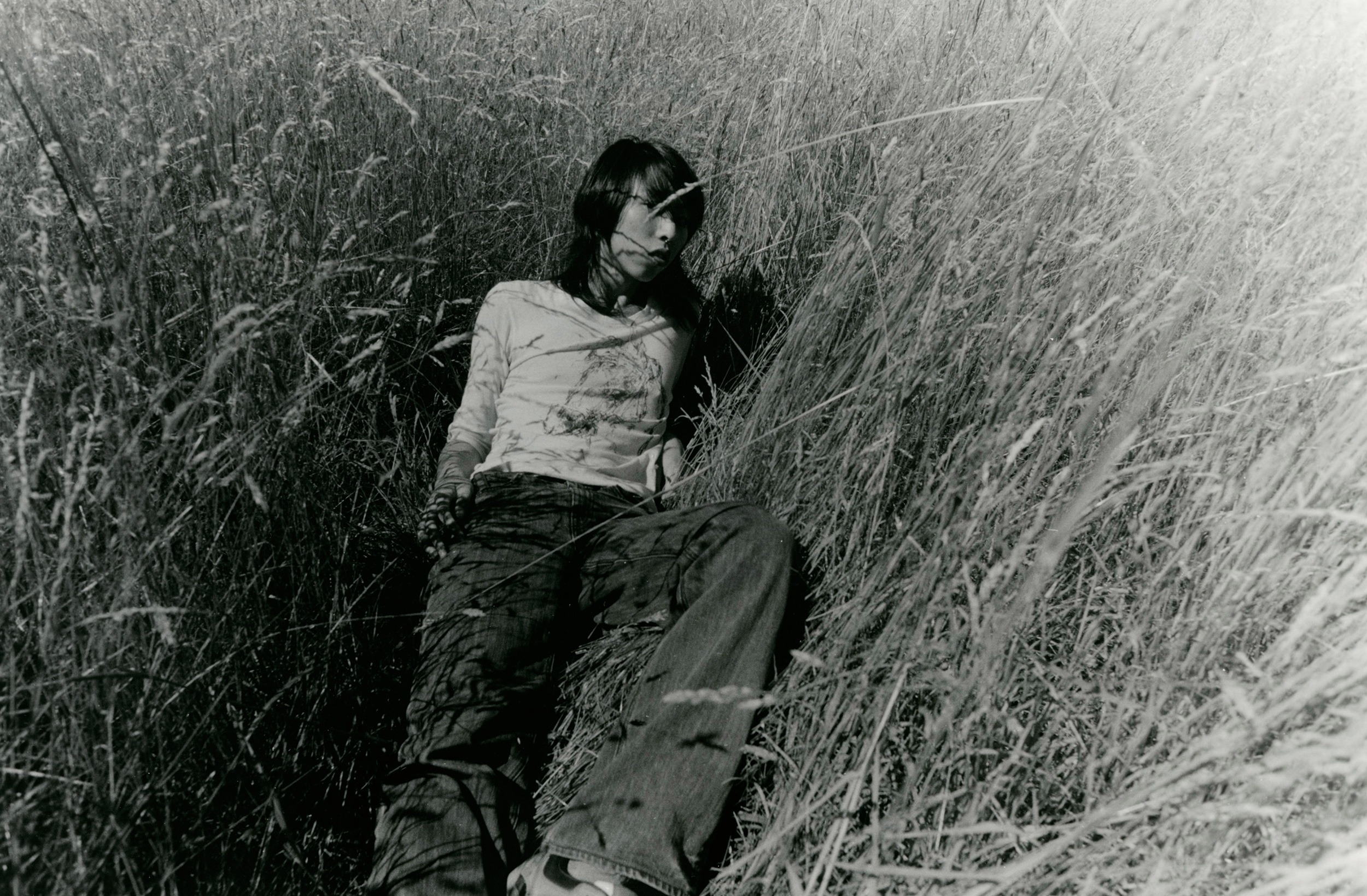

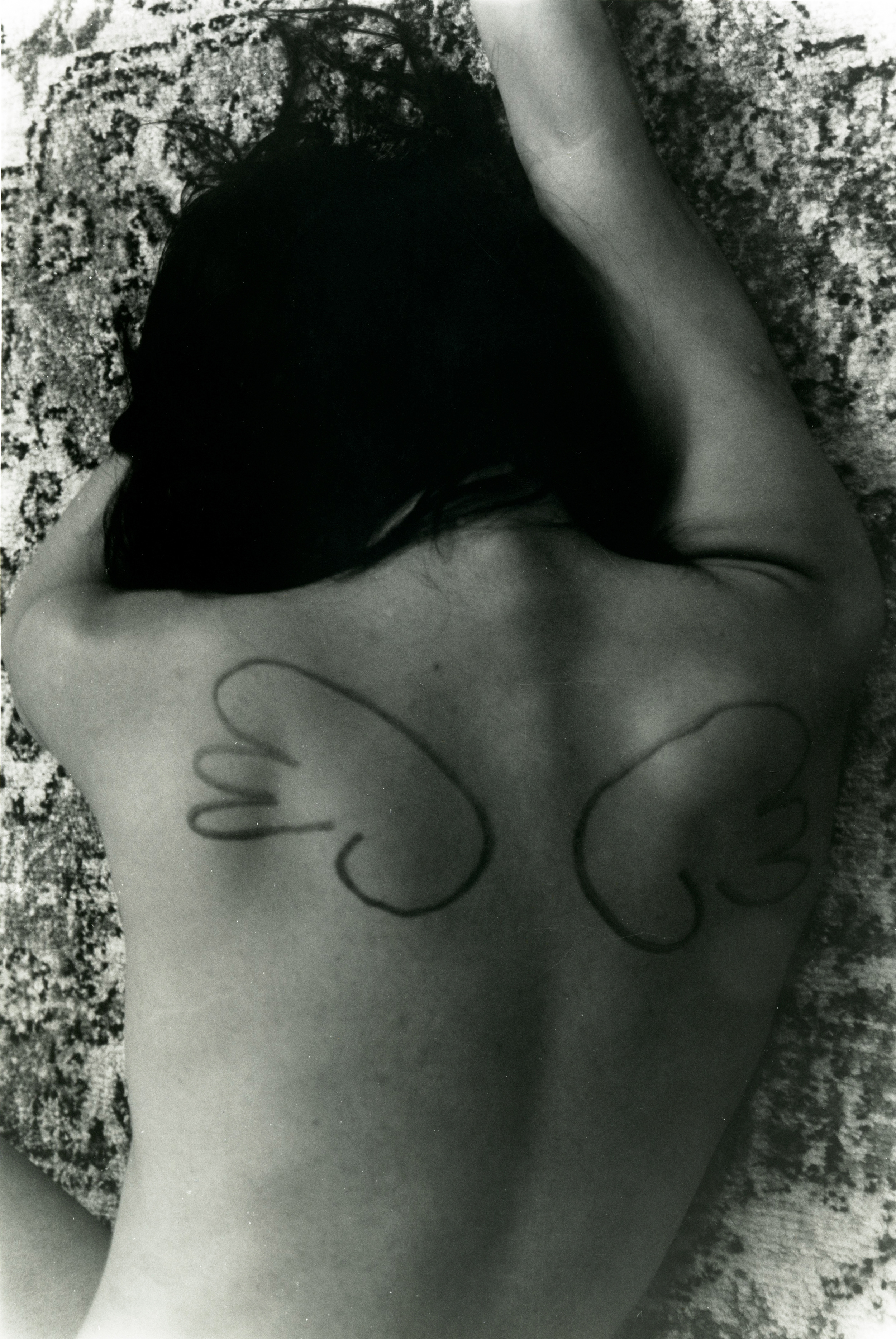

Ambiguous as they often are—a man who appears to be sleeping (or dead?) alone in a car in a vague location and era, for example, or an abandoned room that seems equally plausible as a movie set or grisly crime scene—the images in Kollar's most recent book, Provisional Arrangement, can feel like a fleeting single frame of a complex film. The title represents images that collectively tell an unfamiliar but cohesive narrative—one that, like kaukokaiipuu, seems somewhat contradictory at first (are they temporary and spontaneous, or static and arranged?) but ultimately reflects a natural impulse to connect to a greater human story.

Kollar prefers to keep the circumstances surrounding his images a mystery. The viewer’s desire to fill in the blanks animates the pictures and in doing so tells more of a story than he ever could through accompanying text or captions. From his home in Bratislava, Slovenia, Kollar spoke with me about his process and intentions with Provisional Arrangement, perfectly candid while remaining faithful to his notion that the audience will appreciate and understand the images more profoundly when they examine them long enough to imagine three steps before the frame. For Kollar, each photograph is a collaboration between himself, the subject, and the active viewer.

When did you get your first camera, and what were the circumstances surrounding your beginnings in photography?

A long time ago. From an early teenage age, I somehow knew that I was going to be a photographer. Even though at that time I hadn’t taken pictures, I knew it would [eventually] happen. When I was 17 I bought a camera. At the time it was Communist Czechoslovakia, so probably around 1988. I started to take pictures and then I applied for film school. While I was studying, we worked quite a lot with still images for our training. I was shooting a lot of movies as training and when I finished school I decided to come back to what I wanted and get focused on photography.

So, from the beginning would you say you had a cinematic approach to photography?

Yes, well, I think the visual training came more to me through moving images, because even at that time it was easy to see many films. [Imagery] wasn’t linked to magazines really. It was very much observation-based photography. At school we worked on movies that were on the edge between fiction and documentary. All these approaches came to me very naturally and I was very lucky to work with talented filmmakers. Definitely half of me is dedicated to the cinematic approach.

How do you usually work when you’re on location? For Provisional Arrangement, for example, would you plan a whole day around a single shot? Do you usually spend a lot of time on pre-production or are they more spontaneous?

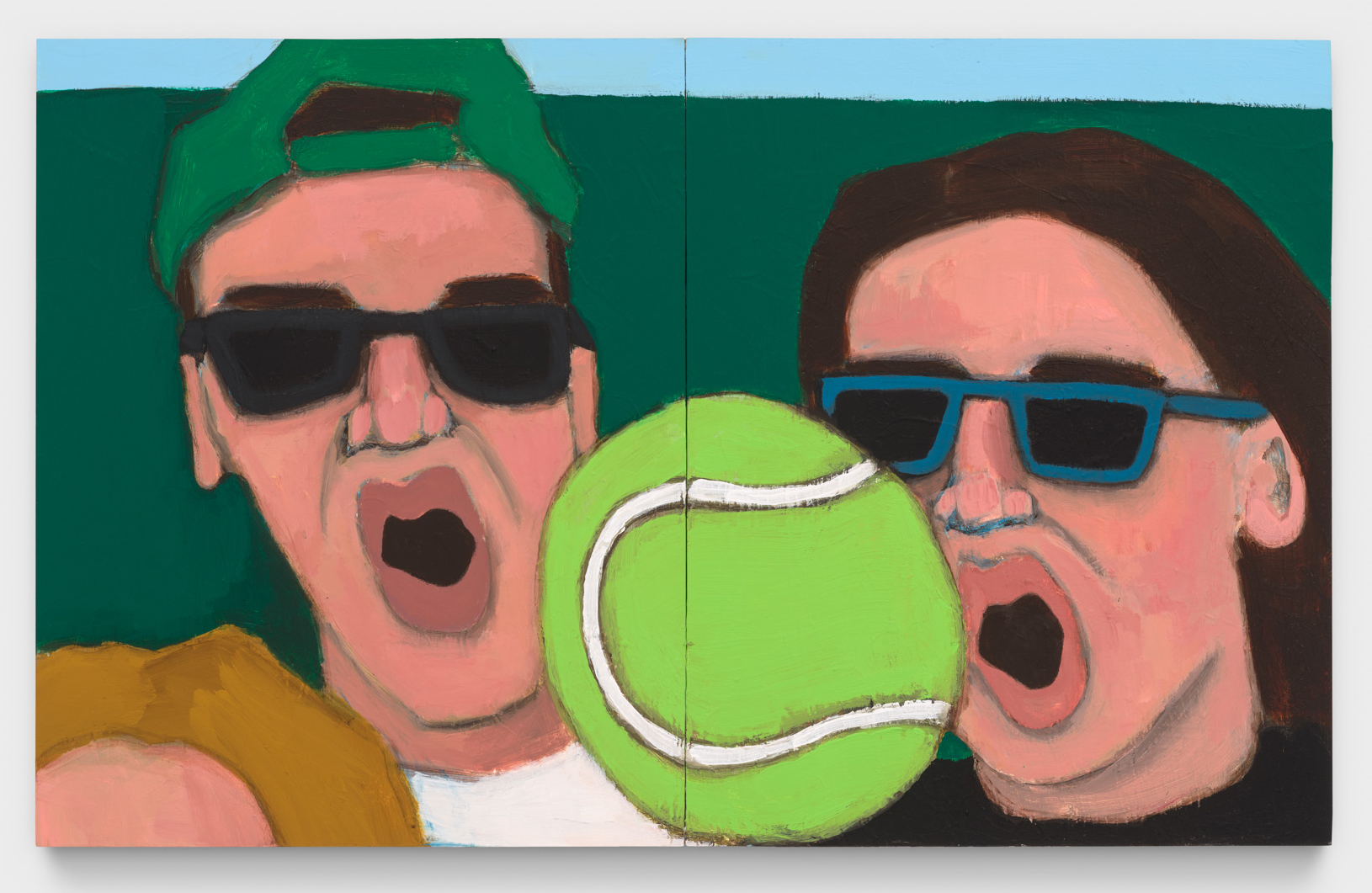

A little bit of everything. [Laughs] For this book, I was putting together two images which seemingly had nothing in common, but had a strong link between them, as a diptych. I wanted the audience, when they look at the precise images individually, [to see] a connection between them that you have to create a third image in your head. Flipping through the pages, you can create a link, or narrative in between those pictures that leads from one point to another. It does not necessarily have a beginning or end. In this case, I wanted to create work that was not linked too much to a particular location or mental space. That was a big challenge for me, not to get lost, because anything could fit in [this particular] book. An enormous amount of possibilities, so it took a long time to figure out how to put it together

I’d love to go through some of the images from Provisional Arrangement and hear the background story if you’re willing to talk about them a little bit in detail, I don’t know if you’re comfortable with that.

There is nothing secretive about the images, but when you look at the book, you realize you have no idea where the pictures are coming from. You understand it could be from anywhere, and the reason for that is when you have a picture, there is always a missing bit, which I call a collaborative part of the picture. Also, with these pictures—I mean I hope so at least—you want to understand what’s going on. I understand your question for that [reason] but on the other hand it’s up to you how to fill this gap, how to fill this missing bit of the picture. I am always afraid to talk about it more precisely, because I am afraid that the whole point of the image is gone. There is a fascination which I like to share and part of it is a question mark or something that you don’t fully understand. The pictures are totally illustrative, so that you get question and answer in one image. When you look at the pictures, most of the time there is enough information to understand what is going on. If I describe it, I think it’s much more boring than something you can create out of it.

When you photograph people, do you prefer to capture moments when they are unaware of your presence or do you like to have an interaction with them?

There are many locations that you cannot enter without a certain kind of approval. In that moment you have to tell them something satisfying so they know the pictures won’t be totally misused. When you approach people, when they can trust you, usually they let you do even crazier things than you would expect. It’s also a communication between you and them, and there’s a certain way they accept being photographed, they become somehow frozen in the different contexts. I’m not usually chasing people down the street, [though] from time to time that happens. [Laughs] I kind of like it when you put things together from different approaches and then those create bigger tensions between the images.

Like 95% of the pictures in the book are observation-based so they are not really created or re-created. This approach that the pictures and situations and people are real, it becomes almost like a record of the present, in a way. It’s important that all this work can become archived for the future.

Do you have any rituals involved in your practice? When you’re traveling do you have an approach to getting a feel for the place?

When I’m working on something, I close my eyes and try to see the non-existent book in total, and somehow you know what you’re doing in a way. It doesn’t mean that [in the end] it’s exactly the same thing as what you had in your mind. I prepare a list of the scenes, which comes from my cinema training. You know your subject and you know the places you can get it, so you are exposing yourself to be facing those situations, to have a higher probability to bump into that kind of situations.

There is a mix in your work between what feels like documentation and a fictitious narrative. I’m thinking in particular of your series TV Anchors. Is there a lot of waiting involved to get that moment that captures this blurred line?

The idea is that you spot something in real life. The TV anchors series started when I was in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. I found it interesting that when we look at the TV screen, [with] which we are so familiar, that if you see a slightly different perspective, and if you take three steps backwards you’ll see a totally different reality. I really like this, something that you are extremely familiar with but an unknown bit, because this is something you don’t see even though you see it every day. I like that you don’t really know where the pictures are coming from.

In a lot of your work, you address the human condition. You talked a little bit about the 20th century and capturing the zeitgeist. Is there something you hope to show about humanity in your work?

That’s such a difficult question. [Laughs] We could talk about it for a really long time. I think all of us like to share stories or something that we [go] through and how we deal with it. Each of us are getting tools that fit us the best. I think the best answer is, we all like to share and we have different channels and ways to share and reflect. I found it comfortable and easy to take pictures. It comes very naturally. With photography, when you look at a picture you can find something again and again and again, whatever your experiences are. I really like that quality of photography.

See more from Provisional Arrangement here.