Sour Girl: Jenny Zhang

I have a friend who says that writing a first book is for yourself, whereas writing a second book is for your mother. How do you think of your parents when you publish work?

That's really nice! I guess I count Sour Heart as my first book, because I started it before everything else. I did write it for myself, but I also wrote it for my family. It feels like I wrote it in a different universe than the one my family lives in. I feel liberated as if I were writing it for myself, but I actually wrote it for my people. Which probably I shouldn't say, because I'm sure my people will be like don't write this shit for us, this isn't representative of us, don't impute our name. I wrote it for my people, as limited or as large as that means.

It’s been five years since your last book, your poetry collection Dear Jenny, We Are All Find, which poet Elizabeth Robinson called amongst other praise scatological. Sour Heart opens with the scatological as a commentary about class. Do you see writing about the body as a way to make these discussions immediate?

I end up writing about the body a lot, because I'm literally in one as I write. I know everyone has various capacities to feel embodied and comfortable in the body that they're in. In some ways, I've been really lucky, because the body I'm in has felt right and I haven't struggled with it. In another world, I'd be some vapid girly-girl who doesn't really give a second thought to my body except how to adorn it. Because I shuttled between worlds, and specifically because I immigrated to the United States when I was a young kid, there's been ways in which my body has become a site of critique; a site of conflict; a site of spectacle; a site to gawk at; a site to mock and to discuss without my consent. I find it impossible to not talk about the body.

These stories are very much about class and socio-economics, and the body is very affected by all of that. What happens to your body when the supermarket in your neighborhood only has expired food? What happens to your body when you go from eating food from one culture to suddenly another culture? It's such an ingrained part of these stories that it felt impossible not to write about it.

You write as one of your characters, “That was the secret to being me back then: if you never say a word, people will think you don’t know anything, and when people think you don’t know anything, they say everything in front of you and you end up containing everything.” How does containing everything feel as a writer, and also as someone who has to then speak about their work?

With double consciousness you also get to be a double agent. In these stories, I write a lot about being able to exist at the boundaries. I feel really lucky to be able to exist in several different worlds. I do wonder if other people who have marginal identities feel the same like why do I have to live in this body, or identity, that is so misunderstood and so little is known about it? I have to constantly translate, explain, announce myself. There's that element of pity.

In return, you get an imagination that's really vast. You are able to care about something that doesn't involve you. You are able to imagine a protagonist that might hate you, and actually wish violence upon you. You're able to have insight into those stories in a way that I don't think you can if you live in the world completely comfortably, without ever being required to accommodate others. I did want to celebrate that, and be really decadent about, that aspect of my imagination.

So much of Sour Heart is written from the point of view of a child, who is “old enough to understand how one of trauma’s many possible effects was to make the traumatized person insufferable.” What are some ways writing from the vantage of childhood allows for these observations?

Childhood is seen as not a very serious subject. It's very easy to dismiss and make fun of. For me, it's really fertile territory because it's one of the only periods of your life where you're supposed to be powerless. Adults are legally allowed to punish you as they see fit. You are supposed to be dependent, but also supposed to learn not to be while having none of the resources to be independent. If you're lucky enough, you can spend a couple of years developing who you are without the limits that start hitting you when you're [an] adult.

These girls are holding on to the last shred of delusion, which is that they can truly be anything they want to be. I say that and it sounds so dark and cynical. Of course you can be whoever you want to be, but you can't control what the world does to you. These girls have almost hit their limit of being discouraged. There's a specter of who these girls grow up to be, and that specter is narrating these stories.

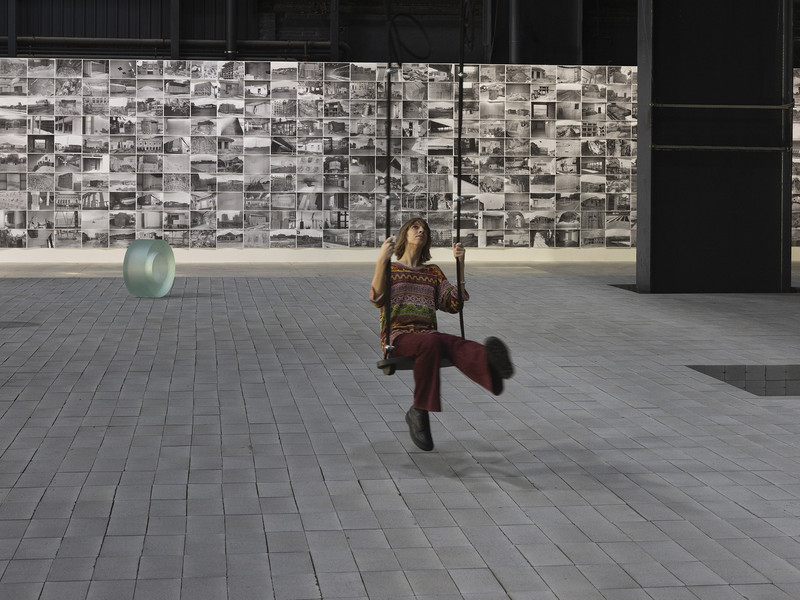

During our photoshoot you mentioned Fashion For Writers, the fashion blog started by Esmé Wang in 2007, which you ran together before she handed it over completely. What is your relationship to fashion like lately?

Esmé Wang is an amazing fashionista and writer, and I've known her since I was 19 in college. She kind of looked like a 1960's air stewardess at the time. We were both in grad school in the midwest when we were doing Fashion For Writers. We were the kind of writers where the pleasures of imagination were truly alive in writing, but also in picking out an outfit. It's creating a character. Who is the person who wears this outfit? It's very dramatic, narcissistic, and self-narrativizing, which I feel is the province of writing and also fashion. When we were both in school in the Midwest, you're very far from haute couture fashion, but you're very close to this other kind of creativity and styling. We just started documenting our outfits. For me, it was more a way to experiment with writing to an audience.

This is a thing that's becoming more and more clear, as I guess we're the Instagram generation. Things that look good in photos don't necessarily look good in real life. I realized that I was dressing for the photo and not for real life. I like hanging out with people in my clothes. I didn't like hanging out alone in my clothes taking photos. Lately, I've been really into clothes that don't necessarily photograph beautifully, but feel good and don't feel aspirational for the body that I'm going to have in a year or ten years. They feel actually fitting for the body I have now.

I want to talk to you about something I really relate to, particularly about girlhood, about being someone who “thinks about themselves with the kind of intensity that is only acceptable between the ages of thirteen and nineteen” (from the essay How It Feels). How does wielding this intensity feel when writing fiction?

There's a unique kind of mythmaking with narratives. Girlhood is a story of desire; innocence; fall from innocence; being desired; being not desired; being desired by the wrong people; by dangerous people; by the right people; by excitingly dangerous people. There's so much storytelling in girlhood. There's so much revision in telling it. There will always be something special about fiction. So much of my girlhood was fictive. I lived in my mind. I made up the girl I thought I was. Whether that's delusional or not, I really felt the happiest and safest in my fictional girlhood. I think the girls in these stories are the same way. There's the story of their lives, and there's the story that they're telling.

- Sour Heart is available August 1st, 2017 from your local independent bookstore & also available for pre-order online.