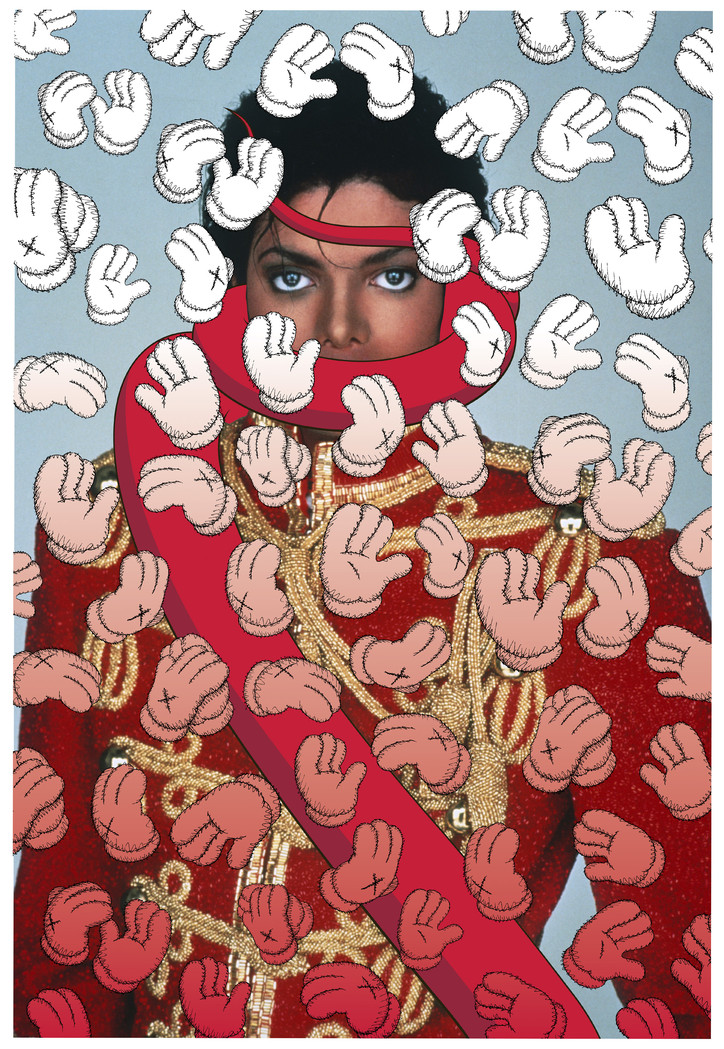

How Do You Solve a Problem Like Michael Jackson?

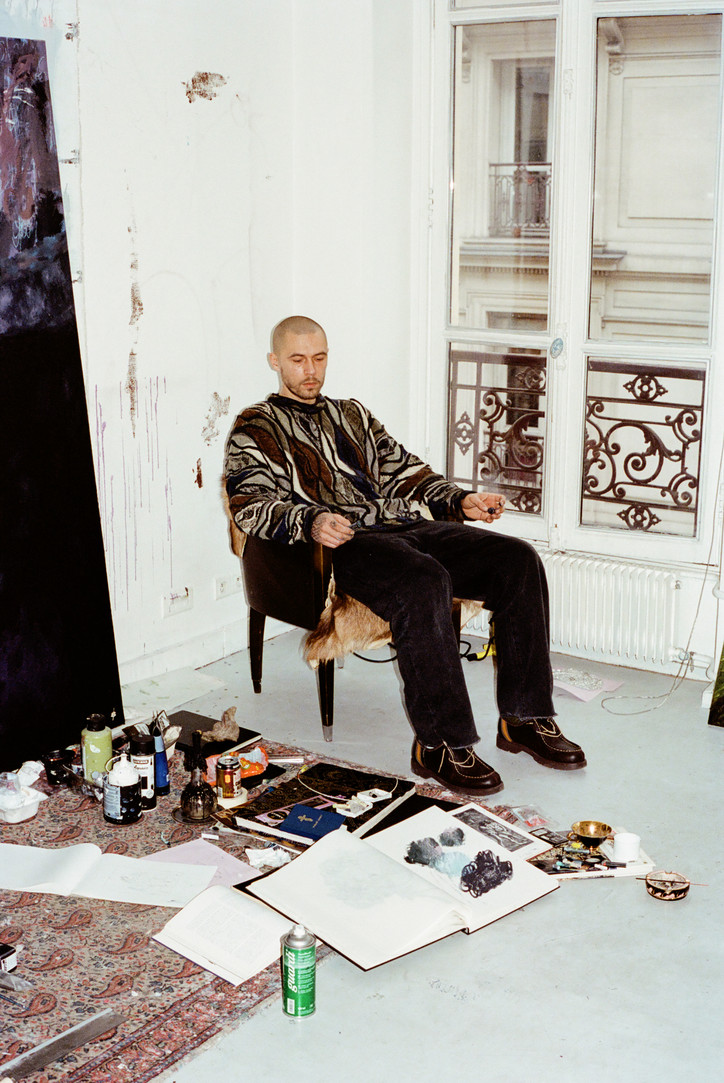

Last week, office had the enlightening privilege of chatting with MJ’s personal photographer, Todd Gray, who has an entire room of work in the show.

You were Michael Jackson’s personal photographer. What did that entail?

That's correct. I photographed him in ’76—maybe ’75. Up until Thriller, I worked for him. Back then, big celebrities—even Muhammad Ali—had their own photographer. But photography was more complex—it wasn’t like you had a disposable camera in your pocket. So, if you wanted anything recorded, and you wanted to have control of what was taken, then you’d have a personal photographer. Basically, he’d call me to come to his house and photograph him doing some leisure activity, or going to an award show, or benefit. One thing was going to Disneyland with him because he wanted shots of him going on the rollercoasters. And then, of course, touring and recording sessions. So, for the Thriller sessions, I was present for that.

What's your take on the show at the National Portrait Gallery?

Well I was there for the opening, and Mark Ronson was the DJ, which was pretty impressive. Hugo Boss underwrote the opening, so there were a lot of fashionistas and so forth—a lot of people skinnier than me. But to answer your question directly, the show was really balanced. There were some excellent critical works and conceptual pieces, like Lorraine O’Grady's piece, which compared Michael Jackson and Baudelaire. Of course, Andy Warhol, who was friends with Michael—he had a great room, and Kehinde Wiley had a massive portrait in the show. He actually took several pictures of my pieces and put them on his Instagram feed, which my son saw. Finally, I get respect from my son because he’s like, 'Dad! Kehinde Wiley knows your work! You really must be something!'

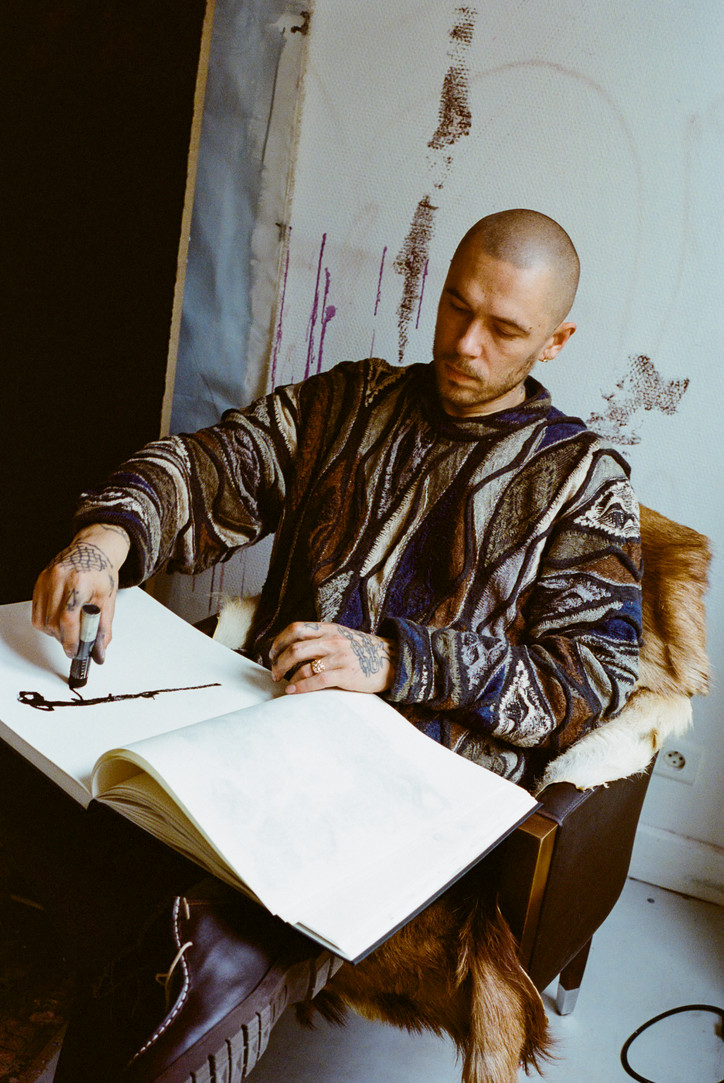

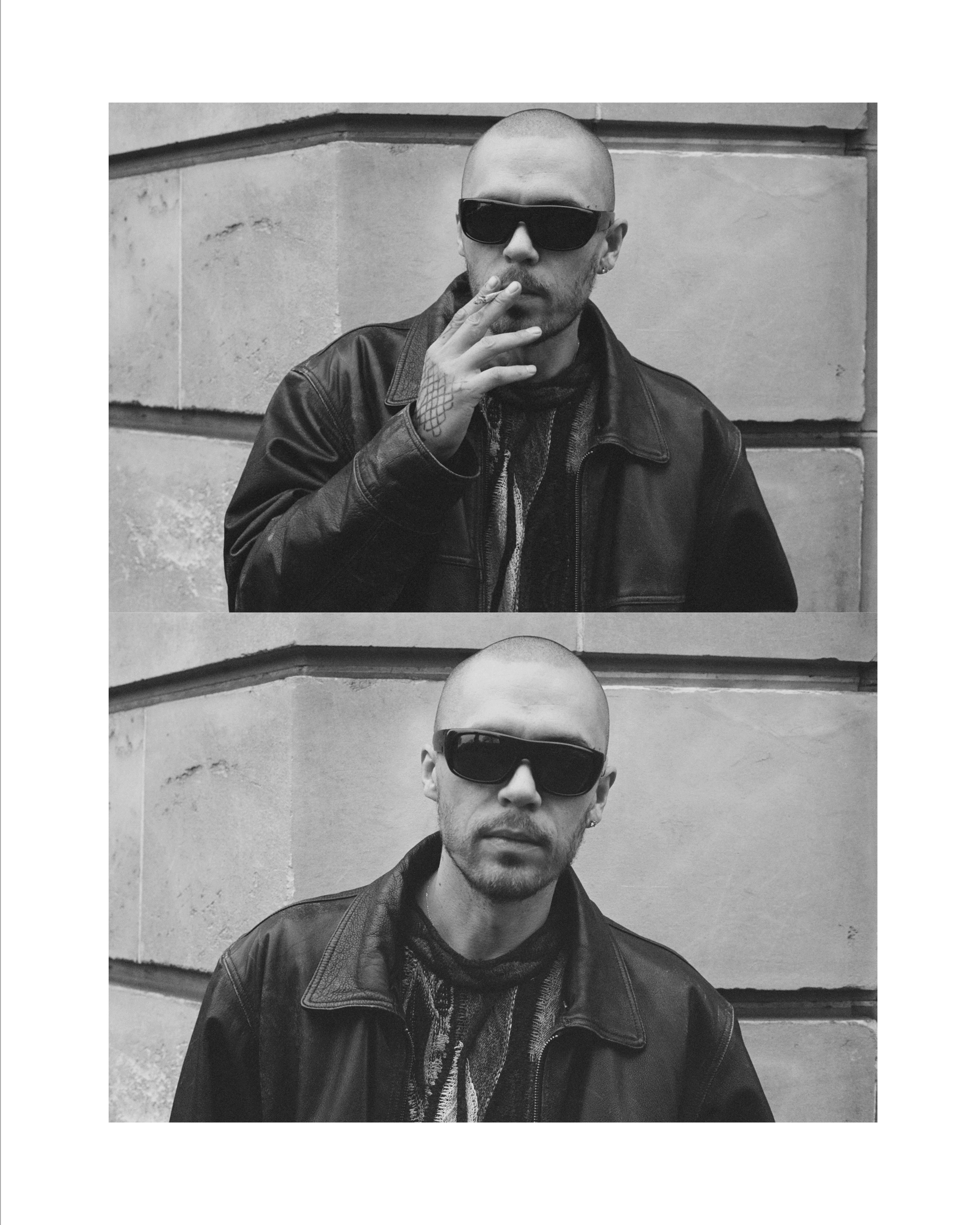

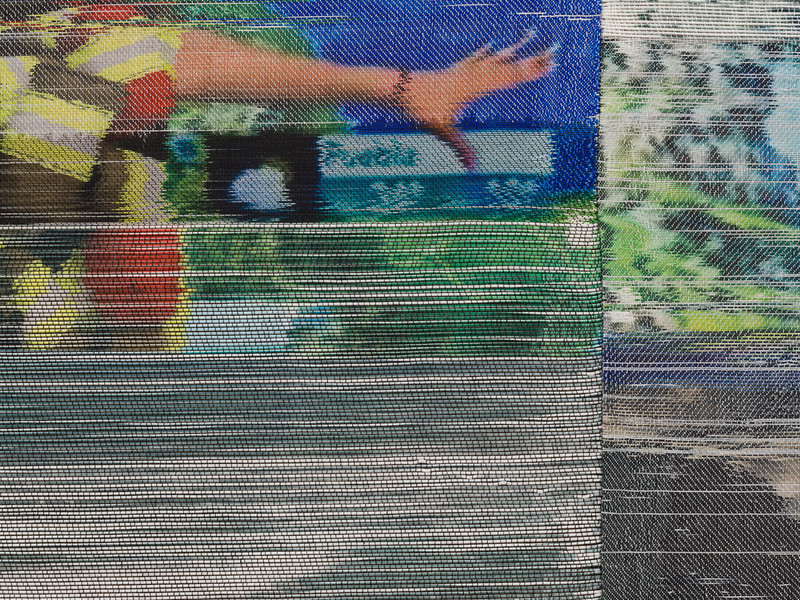

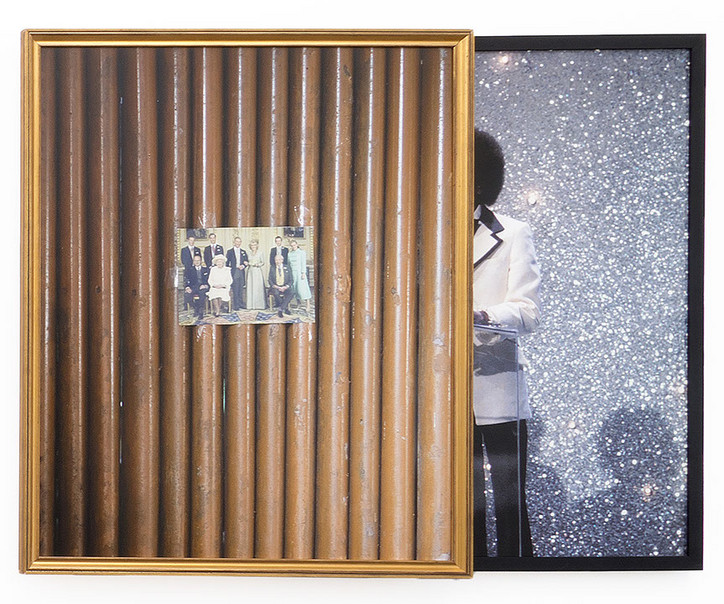

Above: 'Cape Coast and Nickel,' 2014, 'Bamboo Royals,' 2014, both by Todd Gray.

I was originally going to interview the curator and ask him this question, but I think it still aplies: what do you think Michael Jackson represents and why have so many artists used him as a subject?

Well that is more of a curatorial question.

Well, you can answer it—you knew the guy.

He had such a huge influence. I mean, a lot of the works in the show were not made specifically for it, and these are serious artists: Faith Ringgold, Andy Warhol, David LaChapelle, Catherine Opie. They were moved by him one way or another—emotionally, because the effect his music had on them, or from a critical perspective, because this man was such an individual, and he maintained his individuality up against a hellstorm of criticism. So many people, especially entertainers, would bend, and Michael never did. He was going to be him. So, I just see him as a signifier of a person who did not bend to any kind of normativity. And he brought joy, man—he just brought a lot of joy into people’s lives.

But to me, it was his work ethic. I would see him doing scales in his hotel room before shows, turning off the air conditioning in the South during 95-degree weather, opening up the window to let in the humid air, because it was much better for his throat than the dry air from the AC. His brothers weren’t doing that—they were going off, doing stuff, while he was in his room, doing scales and practicing. I honestly don’t think I'd be as successful as I am had I not witnessed his work ethic. It really influenced me to buckle down and take my art seriously, like I saw him do.

That’s so interesting, especially because you don't really think about that when you think of Michael Jackson. Like, it's weird to picture him in his hotel room, doing scales.

He had an immense amount of talent, but that talent was nurtured and cultivated to a very high degree—to an obsessive degree—because he wanted to be the best in the world, period. He took that as his mission, so he took all the pains and sacrifices that came with that. I have photos of him—here he is, Off the Wall is huge, and we’re on the road, and I have this photo of him, right before he went on stage where he’s biting his lip. You can just see the fear in his eyes. Sometimes, he was almost ready to vomit. I mean, here's this person who'd been doing this since he was 6-years-old, yet in his 20s he's still experiencing this anxiety. But as soon as he'd step on stage—boom—he'd become this huge superhero. He'd become MJ. And as soon as he was off that stage again, he was meek and mild Michael. His brothers—they were always just ready to go on stage. But for every performance, the stakes were high for Michaell, and it took a huge toll.

That’s actually something I was feeling from the show—that it taps into this idea of sort of splitting of identities. Like, there’s the icon, and there’s the man himself, and how those ideas become absorbed into our own perceptions of him.

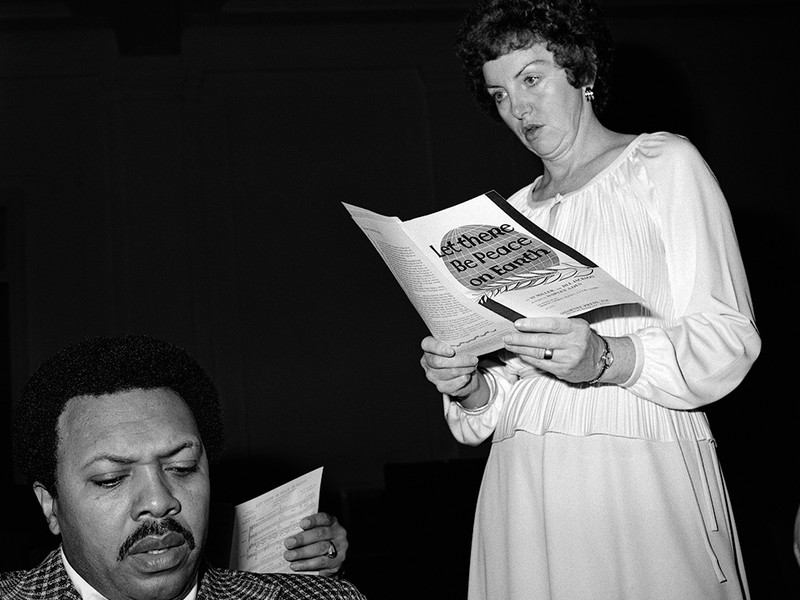

Oh, totally. I’m going to even take it one step further, because I’ve thought about this quite a bit. At rock events, where a whole bunch of people come together and put their attention on a person or a group on the stage, is very similar to ancient cultures and the shaman. The shaman would go into a trance and the whole village would circle around and look at him, or at the campfire, when the most profound storyteller tells a story. Since the '60s, when we really dislocated more, and people really stopped believing in any god—what's that word?

Agnostic. That's when you acknowledge there’s a God, but you aren’t dogmatic.

Correct, agnostic. I see these gatherings as a way to tap into something ancient, because there’s thousands of us and we experience this ecstaty together. Then we rely on Mick Jagger to release that feeling inside of us—it's like a church revival, where you look at the priest up on the pulpit, and you touch the ecstaty. Just look at The Doors and Morrison—you think it’s him, but it’s really inside of you. You're just giving that performer the agency to release what's in yourself. So, for me, when I see those crowds of people, when I see Michael, he becomes that shaman—he takes on the weight of being the changeling, the shapeshifter, that iconic thing, or that force that allows people to experience extreme happiness. I mean, it’s crazy.

I often think that art taps into religion and belief, especially because most art from history is religious. But then, when you think about today, what do we have? We don’t have saints—we have celebrities.

Exactly. So you have these gatherings where there are thousands of people there for one single purpose—for the rock show. I’m sure you’ve seen the DVDs of his performances in Bucharest, and Eastern Europe, and all those places, but the camera goes to the audience and girls are just crying and fainting, like Beatlemania. I mean, that’s religion. And you know, if it were The Stones, you'd know half the audience was fucked up on drugs. But at a Jackson concert, things were pretty innocent. That's just what he causes in people. It reminds me of those ancient religious pagan festivals. He is Dionysus.

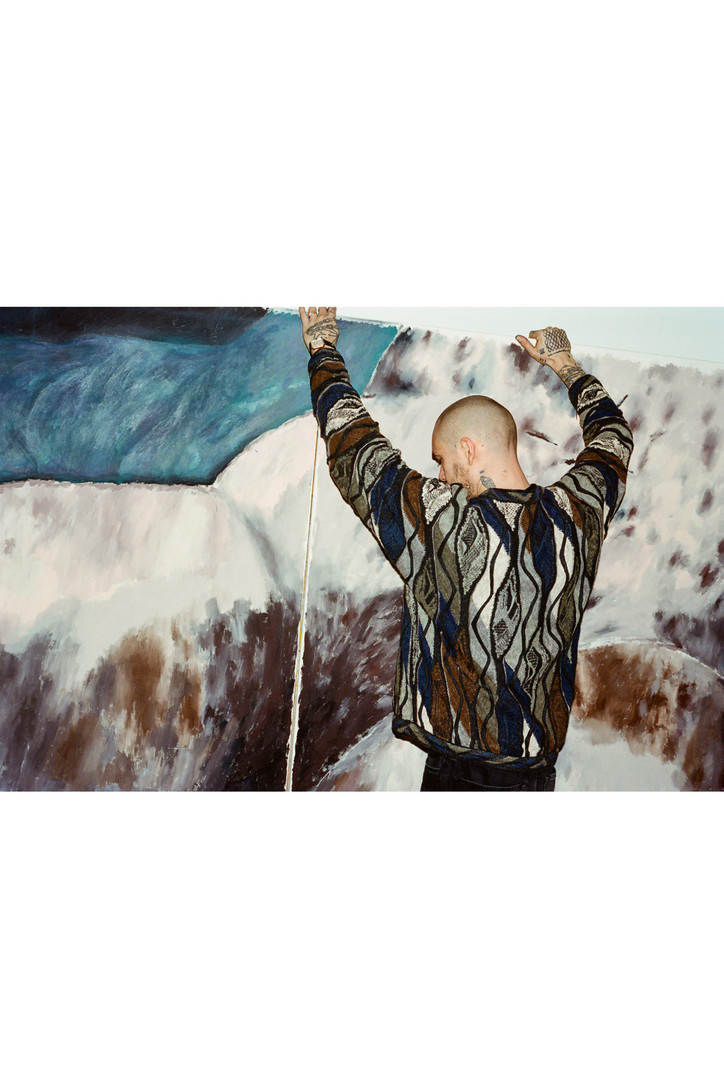

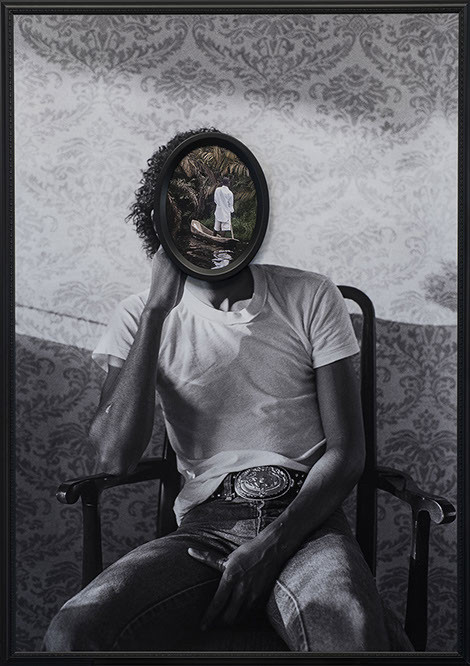

Above: 'Exquisite Terribleness in the Mangrove,' 2014, 'Atlanta by Boat,' 2015, both by Todd Gray.

Let's talk a bit about the work in the show. Can you describe it to me?

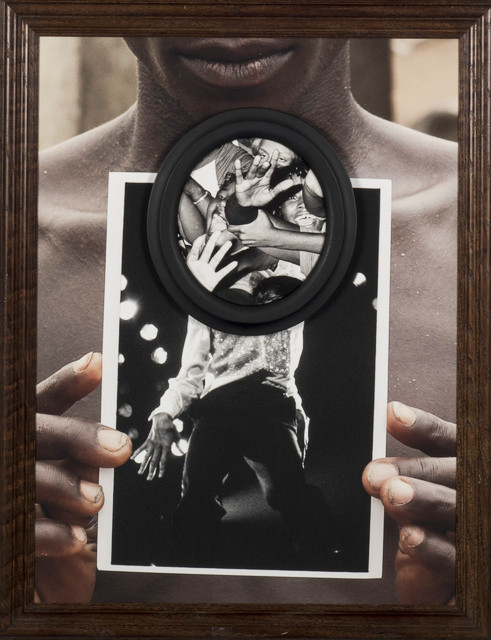

They’re framed photographs of Africa, and photos of Michael, and they’re stacked on top of each other. I did my graduate thesis at CalArts by critiquing and re-examining all of my MJ stuff that I’d taken ten years before as a part of pop culture. Now, ten years later, I’m analyzing it and recontextualizing it as contemporary art. I’m also referencing the African diaspora, so I’m really questioning Michael’s place globally. So, I’m not positioning him as an African-American—I’m positioning him as an African in America. I have a studio in Ghana, so for the last ten years, I’d take MJ’s pictures around and ask people in the bush if they knew who he was, and photograp their responses, and record it.

Did they know who he was?

This was before smartphones, and I was in a place with no paved roads, no utilities—it’s just living like people used to live, and everyone 8-years-old and up knew who he was. I was actually kind of shocked. I mean, everybody. He's the most famous black man in the world—if not just the most famous man in the world, period.

You mentioned connecting Michael to the disapora. Can you talk about that?

Yeah. I’m sure you remember this, but in the early '90s, after Bad, and his complexion started changing, in the black community, the narrative was that Michael was distancing himself from his blackness—that he was embracing whiteness, as evidenced by these modifications to his face and hair. I was of that notion also, and during my graduate years, I was doing this photo text piece where I was showing all these examples of Michael—the term is called ‘mental colonialism,’ and it's the idea is that the colonizers, they ban your language, they tell you your culture is worthless, and basically stir up racial self-hatred, and a desire to be white. Like, first they colonize your body, then they colonize your mind. So, in my master's thesis, I was saying that Michael is evidence of mental colonialism. The idea was actually first discovered by Jean-Paul Sartre, who was a contemporary of Joseph Campbell. After reading him and coming across this concept, I’m writing this thesis and thinking, ‘Oh my God, it’s not just Michael, it’s me too,’ because I realized elements in my own personality—how I would change my pattern of speech so you couldn’t tell I was black, how on my resume I would black out that I had exhibited at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Back in the '90s, believe me, it would be restricted if there were any signifiers of your blackness on your CV or resume. So, once I saw those things I thought, ‘Oh my God, I was distancing myself from my own culture,' and 'I was harboring racial self-hatred.' That’s when I realized, Michael Jackson isn’t an eccentric—he’s a product of white supremacist thinking and American systemic racism. That’s when my whole thought, and my whole relationship with Michael changed, and when I decided to use his photographs to criticize whiteness, to criticize systemic racism.

He’s such a—I don’t want to say obvious—but the connection is really a cool idea.

I just want people to consider it. That’s all I want people to do—just pause and consider it. I don’t want people to keep thinking that he’s crazy, he’s an eccentric genius—yes, he is an eccentric genius, but he’s also a victim of systemic racism, and it got in his head as it does to most people, and any Other—queer Other, woman Other. Any non-white patriarch. And contextualizing Michael, like this exhibition does, really speaks to how important he is outside of just music culture. I mean, he’s very significant. I can’t give it enough weight. Look how many serious artists have actually used his work in a variety of contexts to reflect back on our culture.

'Michael Jackson: On the Wall' will be on view through October 21, 2018, at the National Portrait Gallery in London.

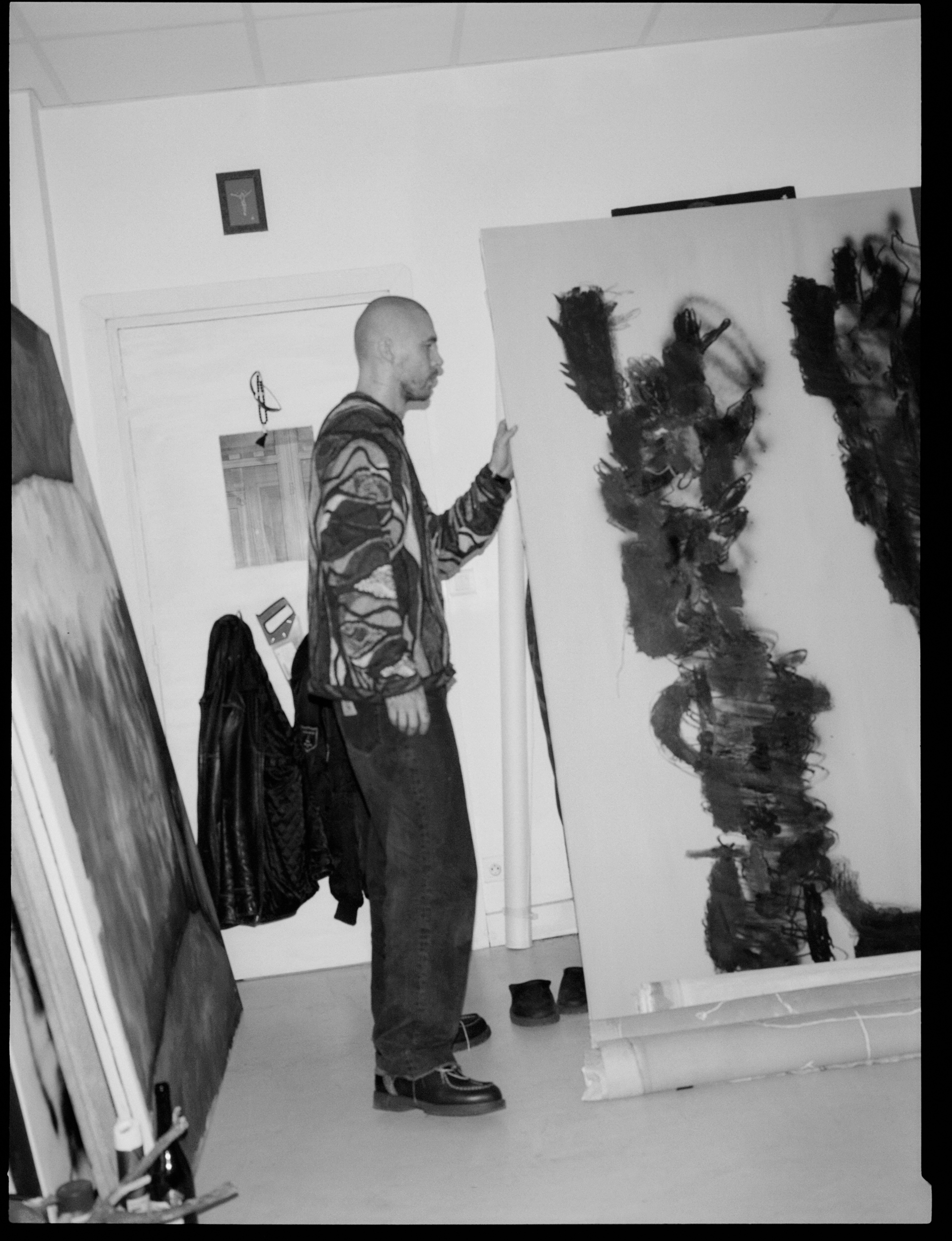

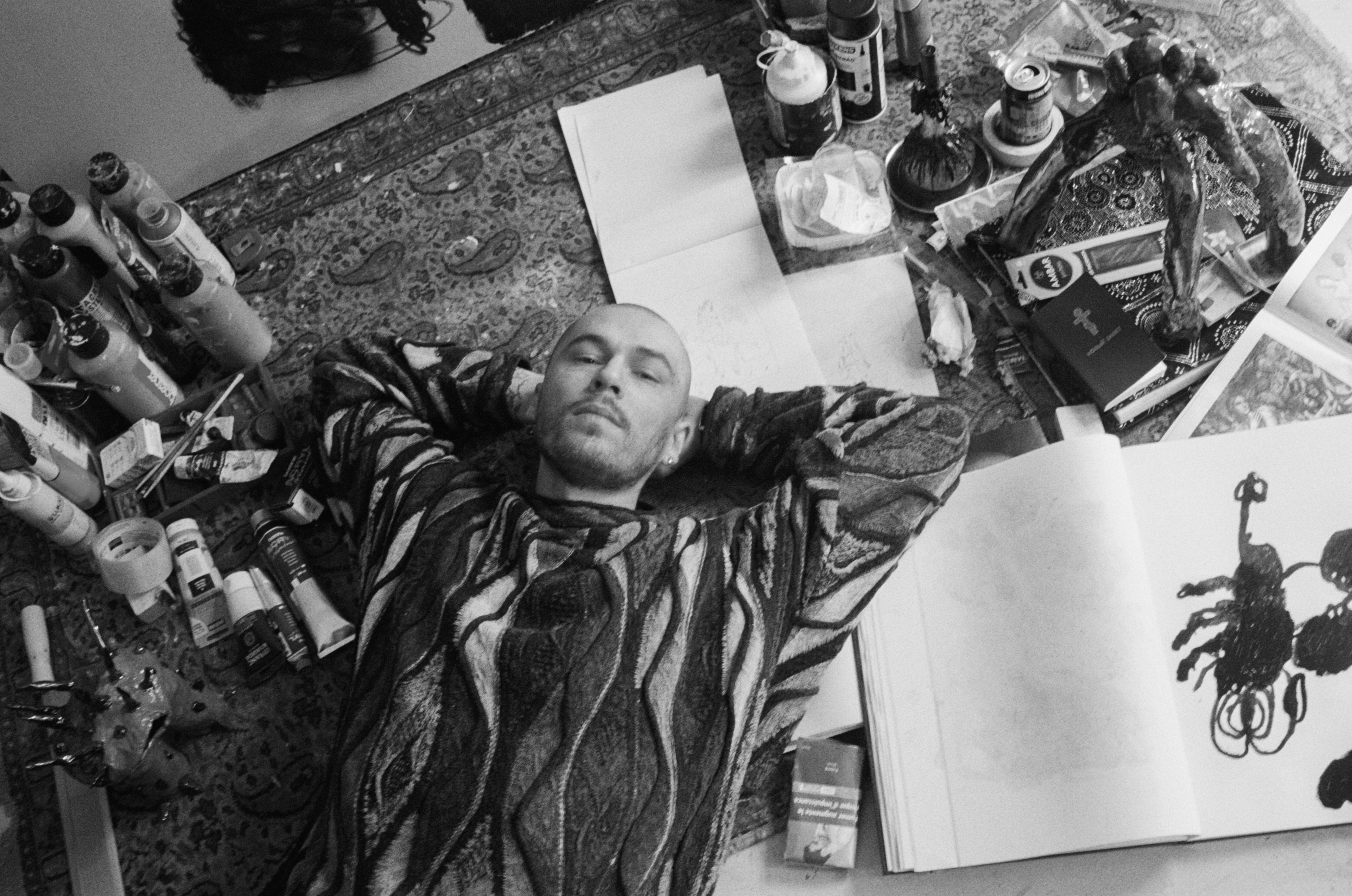

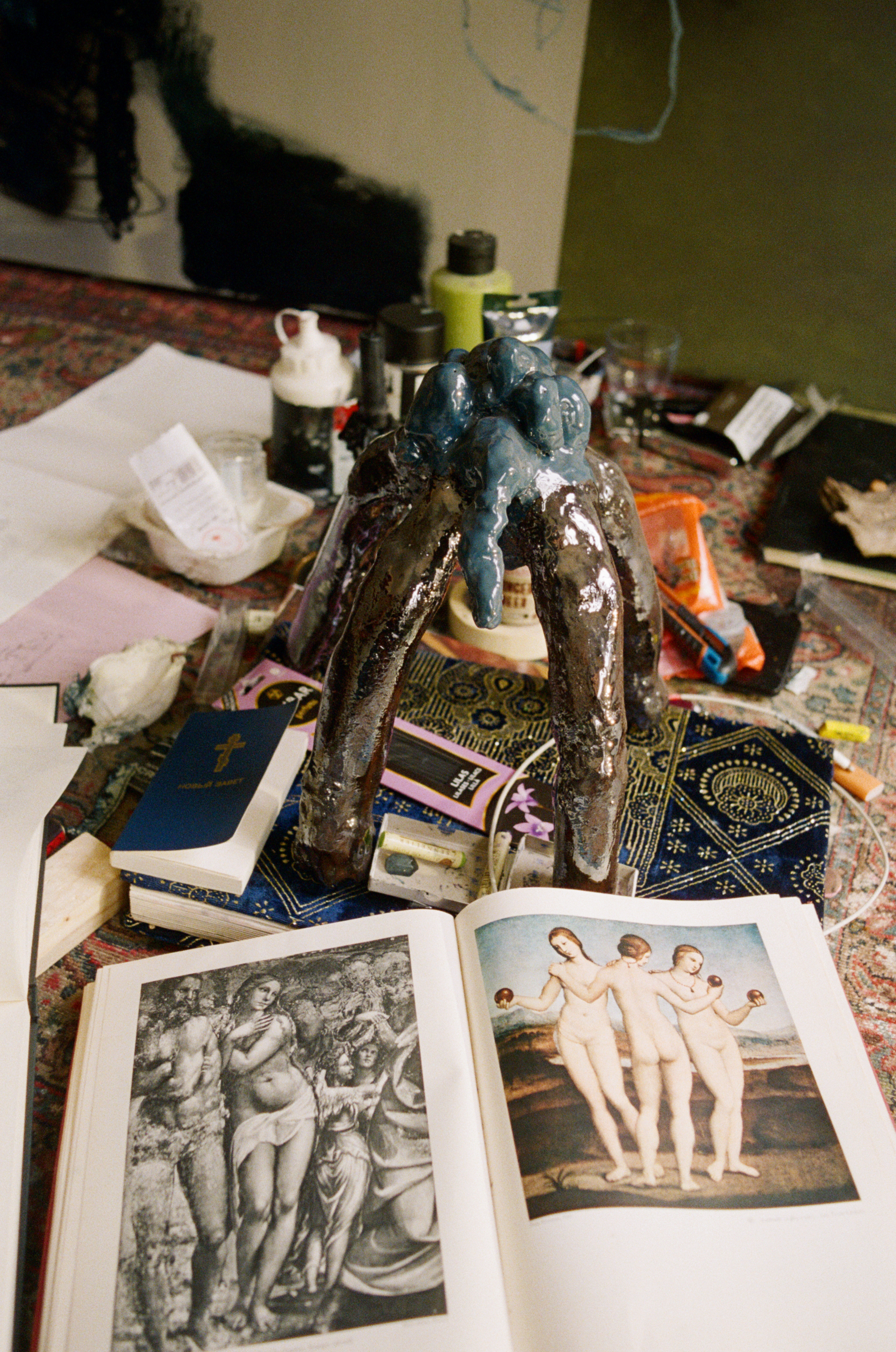

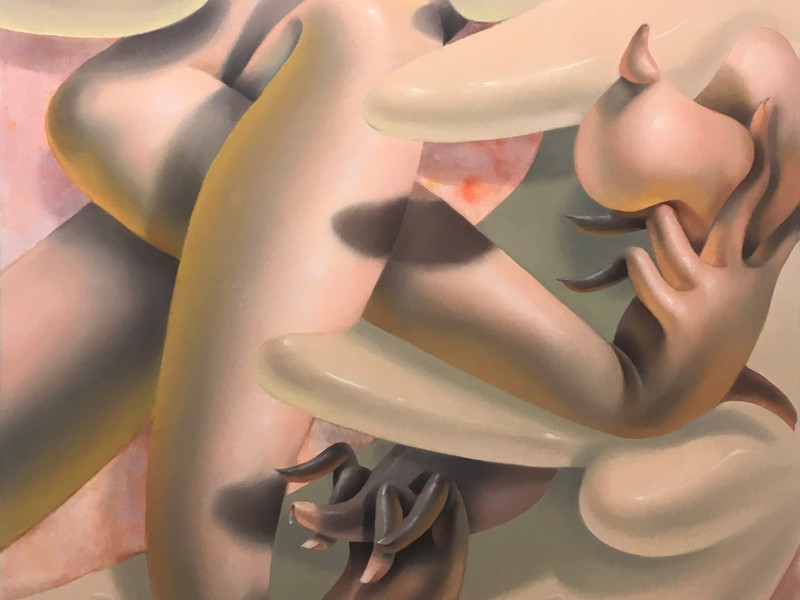

Cover image: 'Hands,' 2016, Todd Gray; All images courtesy of Todd Gray and the National Portrait Gallery in London.