24 Candles

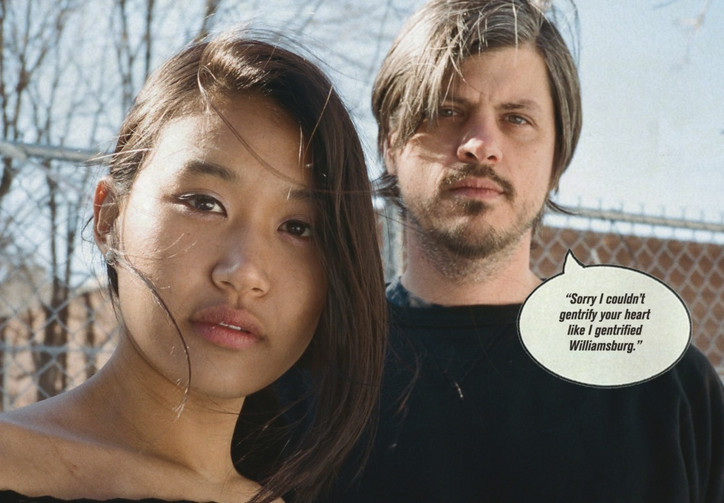

As a gift for Leila Spilman's birthday, Torbjørn Rødland photographed her and her friends wearing clothing Spilman made under her own unestablished label LSCO. Also included are a Thom Browne jacket and Saint Laurent dress.

Stay informed on our latest news!

As a gift for Leila Spilman's birthday, Torbjørn Rødland photographed her and her friends wearing clothing Spilman made under her own unestablished label LSCO. Also included are a Thom Browne jacket and Saint Laurent dress.

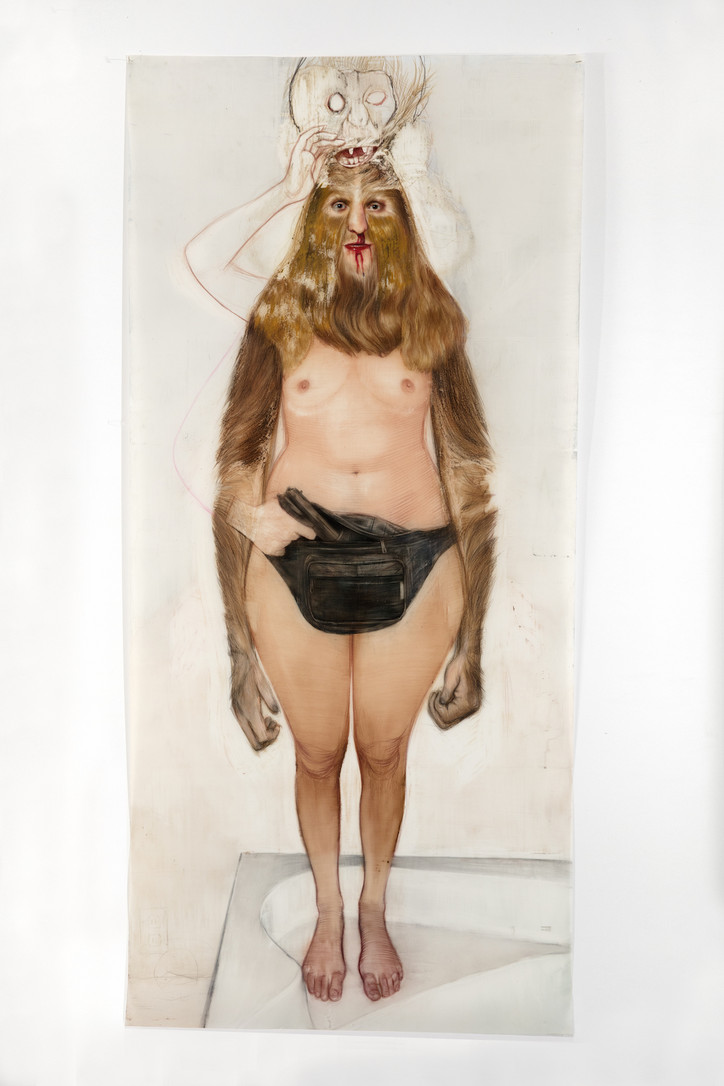

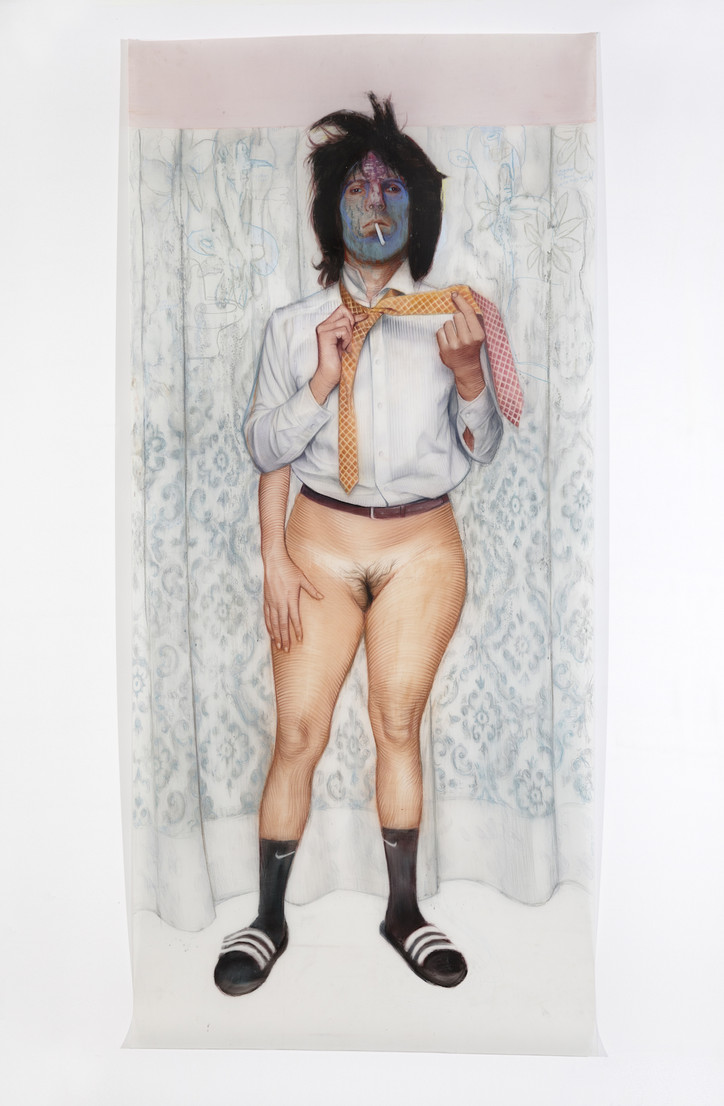

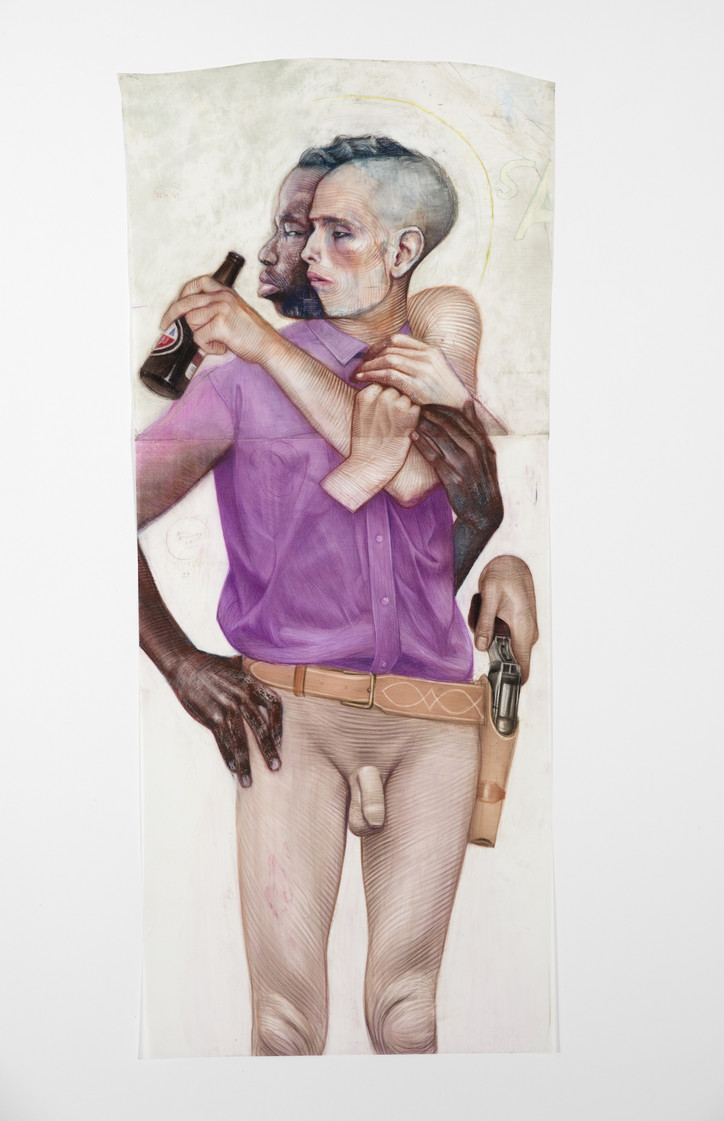

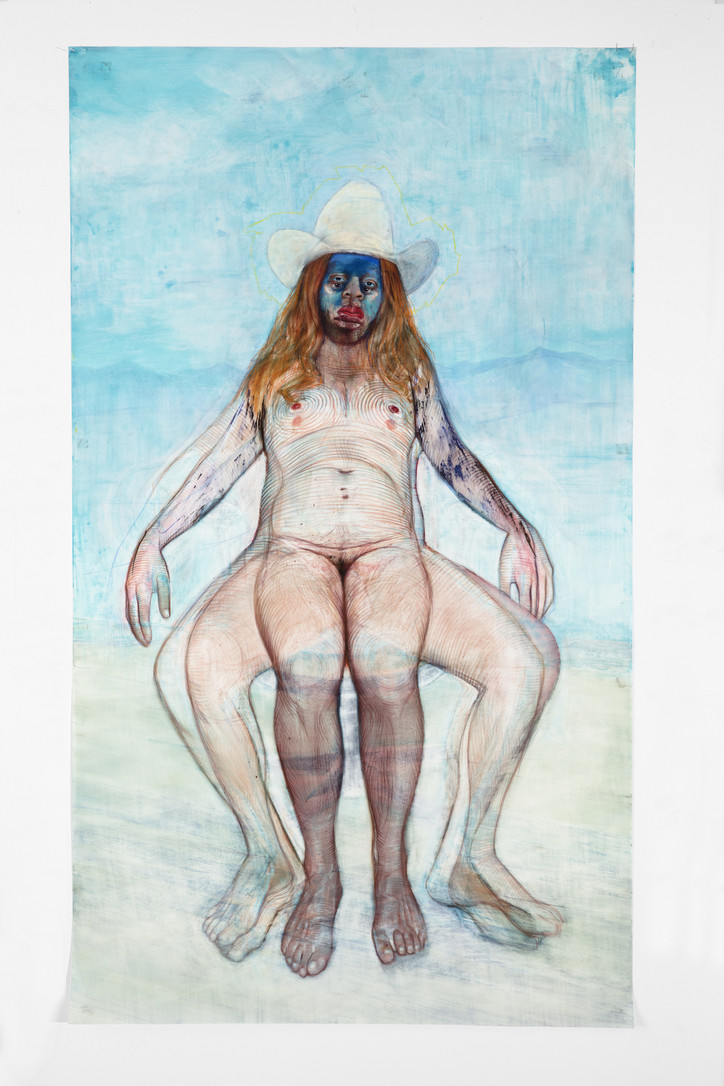

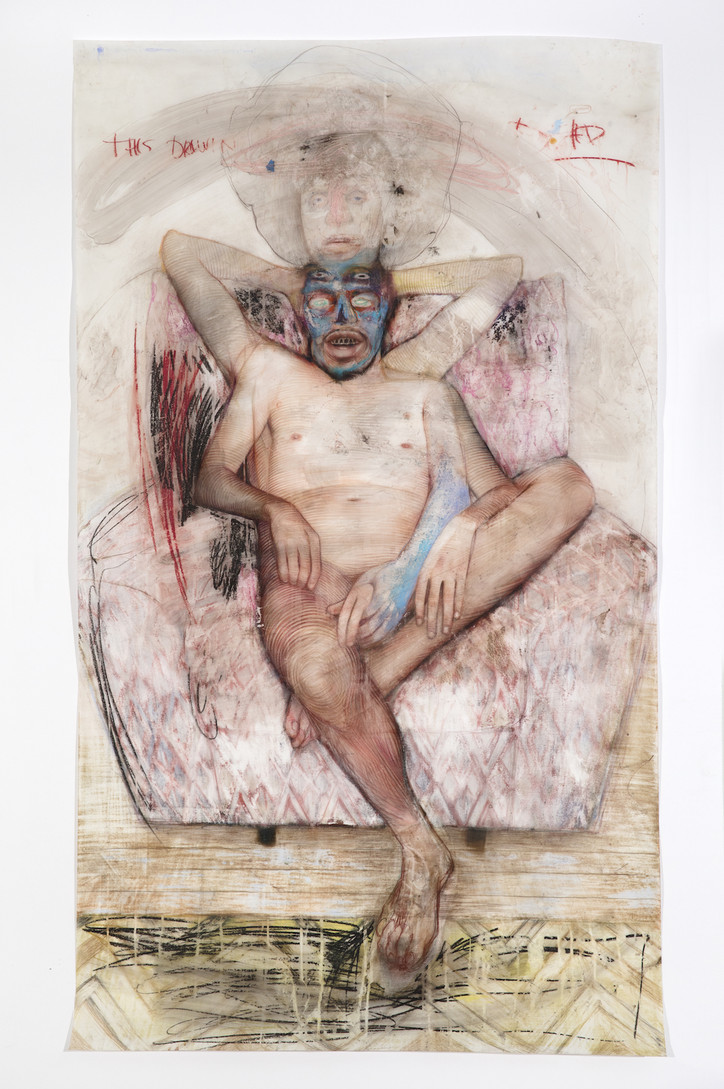

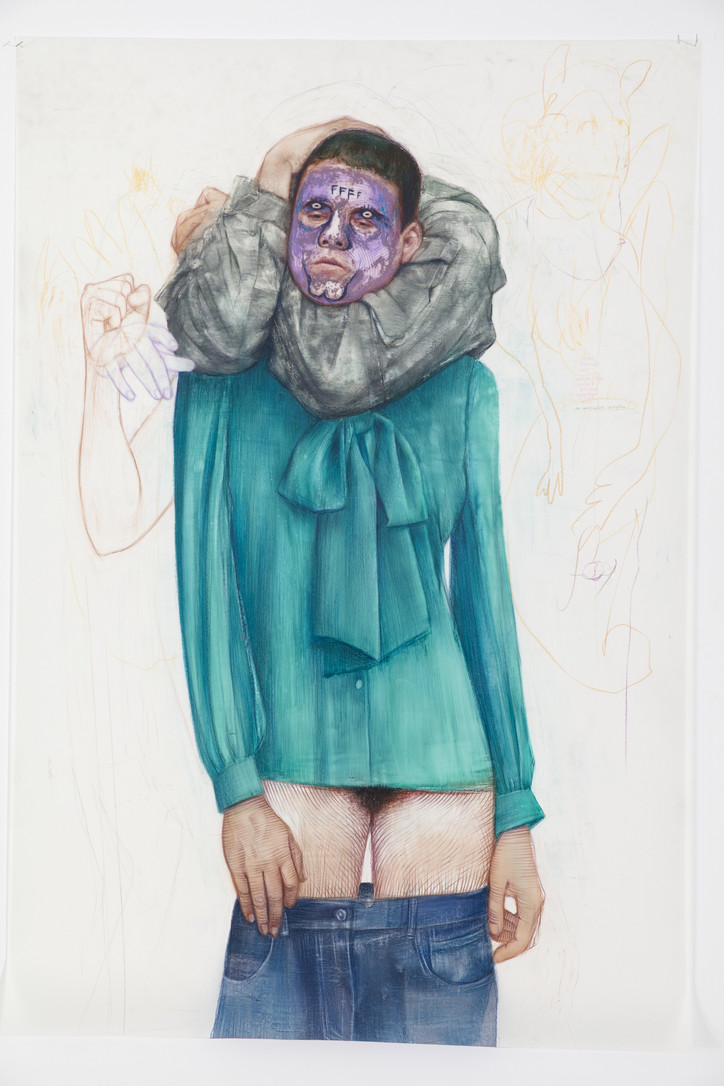

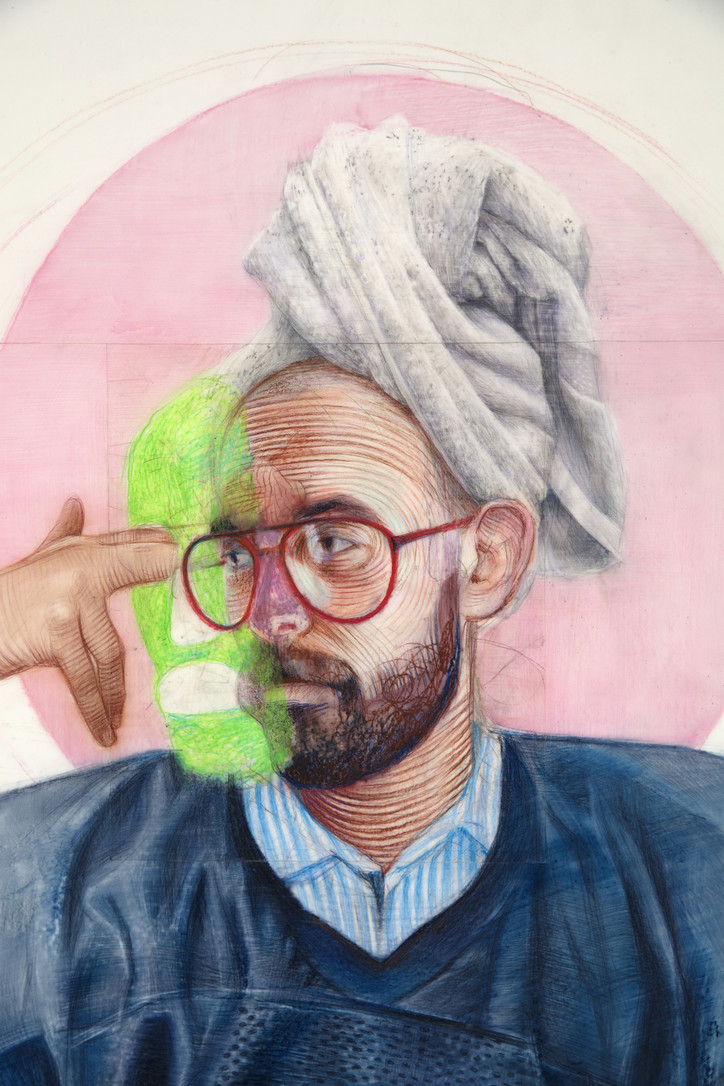

These are creatures that visit us at the moment a dream shifts towards nightmare (or, perhaps, vice versa), guiding us into a post-gender, post-identity, post-anthropocene, post-techno dimension where everyone is absorbent of everything — the only limit being the limits of our own parasitic imaginations.

Like modern-day iterations of the famed magical picture of Dorian Gray, these figures have absorbed some of our strangest anxieties in a brave new world saturated with technology, developed and pupated in the studio as if of their own accord, and have been retrieved, as if from Wilde’s attic, to blossom or wilt as they choose in the cold light of day.

office sat down with Geoffrey Chadsey in his studio in DUMBO to talk about these odd pictures, as well as werewolves, Big Foot and, of course, tits.

I’m curious about your process.

I’m a draw-er, I have a master’s in photography and a day job as a photo editor — I can’t take a picture to save my life, so I steal a lot of photographs. The rhetoric about this stuff in the 90s and the 2000s was all about appropriation, you could call it a queer strategy, this pilfering of the archives to build up something new or refurbished. So I have this huge archive of photos I’ve stolen from every fucking site out there, and I did a show — I used to these scenes I would build up and there’d be these art history references in them, but then it became this Where’s Waldo, like people going and trying to find the Degas reference or where’s that movie reference, which is fun, it gives you something to talk about, but I felt like, no one’s talking about the fact that there’s naked dudes staring at you, I just felt like it became like this kind of decoy, almost.

So then I did a show with Jack where I stripped all the allegory out of it and they became very surreal images of naked guys staring at you. And then suddenly it became awkward to talk about those at all, so then I thought maybe I should get less…. literal, less labored. So I removed backgrounds and started focusing on the body, and then as I was drawing them I kept changing my mind. This show has work that is five or six years old that I dug up, it becomes this thing that I revisit again and again. So I’ve been erasing into them, drawing over them, sticking drawings on top of one another, sometimes I start taping sheets of paper on top and keep extending the body. So they’re these little Frankenstein’s that keep moving around.

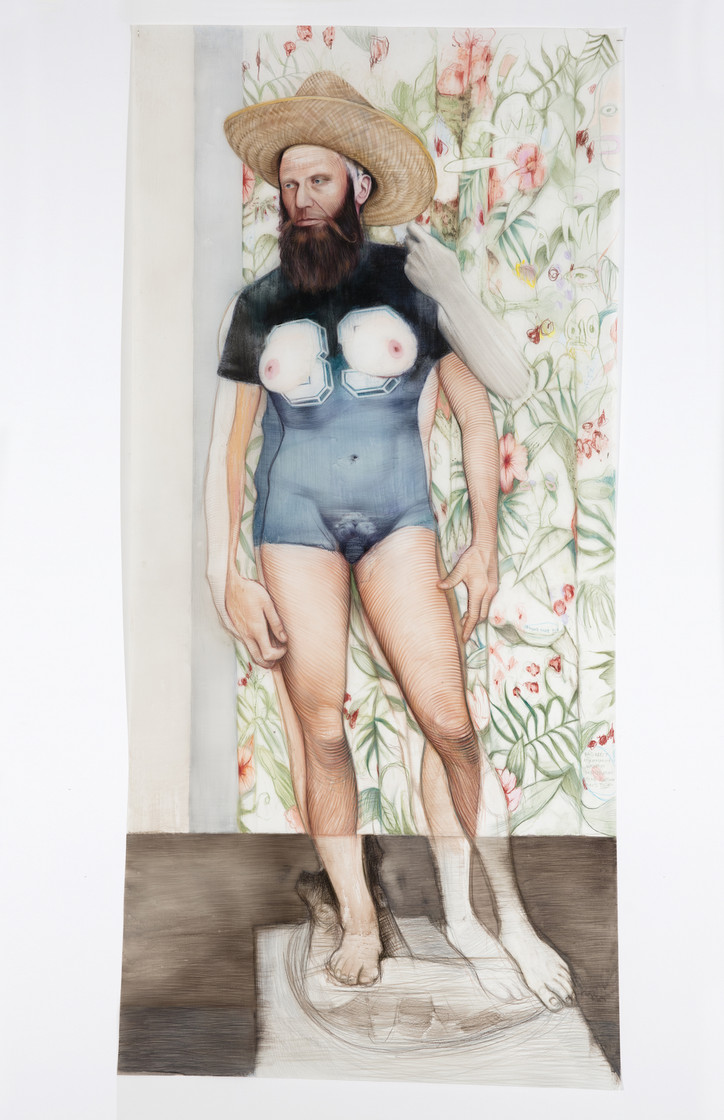

When I was drawing on them, honestly I can’t remember why but I just started putting tits on things. I guess it was kind of a play on the joke of “what’s a gay man’s worst nightmare” to somehow be seen next as a woman, so I was like, alright, I’m going to smack some tits on here. And then with this show, I kept erasing all the penises in the drawings, I was like, “it’s time to go back in the closet, penises!” I just felt like I was occupying that stereotypical gay male artist of, “I draw naked men,” and it’s just like the most boring, tired, thing.

I don’t know if you know Leslie Lowman, which has become an entire archive of gay male nudes, they have this crazy huge archive, I don’t even think they know the extent of it — in the 80s and 90s in particular, people were just dropping dead, it was like, “get this artist archived,” but you walk into the back room and it’s like, whoa!, naked men everywhere.

We were talking before about the definition of “queer” — what does “queer” even mean, do you think?

There was this girl I just met who said she was ‘queer,’ and it made me laugh a little — she was saying ‘queer’ a bunch of times and I was just laughing, I was like, “Oh my god, I can’t believe these straight girls are using this word so handily.” I’ve been thinking about how that word is just so branded now, it’s just being applied to everything, this whole gender spectrum, sexuality hoo-ha, it’s become this like go-to term now for gay lesbian whatever — whatever that big melting pot is now.

The whole point is that the word ‘queer’ is supposed to be unidentifiable, it’s like this moving target, there are symposiums on how you can’t define the term, meanwhile you open up a magazine and they’re like, “this CW show explores queer identity blah blah,” and you’re like, “wait, what? that’s not supposed to be in print!”

There are lots of cowboy and country references — what does the cowboy represent for you and how are you toying with that?

That is kind of new. Like, I hate cowboy hats. This show came about pretty quickly and I was joking about how to make some of these new and I was like, I’ll just stick a hat on it. So that was an old drawing, I started to build up on it and there were so many iterations to it. Of course the cowboy hat alludes to the stereotypical straight masculinity, and now Trumpism, so it just seems like this demonic object that I wanted to play with. Obviously it’s a huge prop in gay male porn fantasies, but at the same time in person when you see a cowboy hat you might think twice about, you know, engaging in conversation. I have this drawing that I finished in 2007, but if a drawing doesn’t leave my studio it’s fair game — it’s like, fuck it, if you’re around, I’m going to work on you again. So I came back in 2014 and added a bunch of limbs to it, and then it was again sitting here, and I guess it just needed a cowboy hat.

The tits are so good.

The pendulous tits — I spent on Google — some of the search terms, that’s the best thing about Google is you can type in the most specific thing you’re looking for like “pendulous tits,” — and for some reason I just wanted these huge fucking tits on this creature. And then the sock puppet came up at the end. Sometimes it’s like — I work on them so long that I honestly don’t know how people look at them. I get that they’re disconcerting, but I want them to be kind of funny too, so I have to remind myself to give these little nods to make people giggle.

What is the world like that these figures occupy, do you imagine?

I think that they first started coming out of this question that was asked of me in grad school 25 years ago, when this photographer, Larry Sultan, he’s dead but was the most amazing teacher, asked me why I wasn’t doing work about effeminacy and I was kind of taken aback, and was just like — it’s one thing to be like, “are you gay,” it’s another to just say, “you’re effeminate.” It’s just this instant recoil. My defense at the time was that that’s not a thing, that’s something that straight people, dudes point out, like a void or lack. But then as I grew older I realized, no, it is a thing, and maybe it should be embraced, and maybe it should be terrifying. So I felt like while I was drawing these it was constantly in my head — what is this ‘effeminacy,’ which I equated with a failure of masculinity, which again was the joke with the tits, but I wanted it to be this thing that you could not look away from. So not being stereotypically clownish or fabulous but being… terrifying.

Well that’s a perfect lead in to my next question: I find these pictures kind of frightening, do you intentionally cultivate a sense of horror?

I think it’s that whole idea of the uncanny — honestly, I’m scared of these being scary. I just feel like there’s that whole kind of goth aesthetic especially artists licking their wounds from their break and belonging, especially with figurative work it just gets kind of… gross to look at. And I don’t want to be in that space, so right now I’m riding that edge a little.

Do you mean pornographic?

No, I guess I what I’m thinking of is this trend of what I like to call the ‘hyperfigurative,’ where you’re kind of equating really good drawing with artistic talent — it’s just over-articulated, the figure is over-articulated in that every fucking spot of the drawing is drawn but also the feelings are over-articulated. There’s just no ambiguity, like I don’t want these drawing to be about anything really, I’m trying to have them… it makes it hard to talk about, really, but I want them in this kind of wordless space — these aren’t about, you know, ‘what’s it’s like to be a… whatever, a gay white man in America.’

There’s something about this feeling about displacement that I’m clearly aestheticizing that I want people to look at it and feel and get kind of excited about it. I don’t want to be repulsive — but that’s that whole thing of pushing and pulling. It’s like, alright, this drawing is fucked up so some people are like, ugh, why the fuck am I looking at this — at the same time I’m thinking about, maybe not the bodies themselves but how they’re made erotic, I want it to pull them in, like ‘oh my god this is really beautifully made,’ but not shut them out either, being like, ‘you can’t do this.’ So that’s that whole precarious feel that I’m trying to operate in, if that makes sense.

What was a horror movie that really terrified you as a kid?

I was terrified, like batshit crazy, flat-out horrified by Big Foot — this was the 70s. There was something about that footage, which now is so clearly fake, but it’s done so beautifully. In some ways it seemed like it had these pendulous breasts or whatever as it’s walking in the woods, and then it just turns and looks at the camera — it was that weird engagement. I’m telling you, it scared the bejesus out of me. Why were people obsessed about it? I have no idea. So Big Foot and then… werewolves — I just could not abide by werewolves, there was something about them. Of course now it seems so corny, right, because the werewolf is the ultimate gay figure, this like, this beastly other is constantly erupting and he or she can’t control it and then they kind of go out and reek havoc at night and then reconcile themselves with this demonic, other thing, and then piece it all back together again. I wasn’t terrified of being a werewolf, I was terrified of being eaten by one, I don’t know what it was about it, I mean the transformation always scared me in those movies, I don’t know if you saw American Werewolf in London, but there’s that scene, I guess there’s The Howling, there’s a lot of great werewolf movies where someone is being stalked by a werewolf, and then they really draw out the stalking.

And then, to top it all off, is Alien, which is still one of my favorite movies, but my dad took me to see it, he saw it first, I was like eleven when it came out, and then I read the book, I was so dead set on seeing it, Star Wars had just been out, every boy was like, ‘space! spaceships!’ and I remember my dad coming back and being like, ‘it’s really fucking scary,’ and I said ‘I don’t care I still have to see it,’ so we went and saw it and I was like — it’ s a genius film, they were doing like a Casavetti film but as a horror film, so everyone just seems like pissed off, blue collar, everyone’s talking over each other, they’re all terrible actors — but when the thing burst out of his chest, I just lost my mind, and in the theatre I was hysterical, and my dad was like, ‘oh my god, I broke my son.’ He didn’t know what to do, he was like, ‘am I supposed to take you out of the theatre?’ and I looked up and then started laughing, I was literally hysterical. But I’m a New Yorker, I’ll go to therapy — actually my therapist said, ‘you shared this cathartic moment,’ my parents got divorced, so he said, ‘you figured out a way to to share this catharsis from real life without actually addressing it.’ So now Alien has become this beautiful father-son moment even though it was so fucking horrifying.

Would you fuck, marry or kill your art, would your art fuck, marry or kill you?

Oh my god. Actually, the joke is that my drawings are relationships that go on way too long, so I would say kill them because I work on them way too long — so I’ve already married them, and then they’ve stuck around way too long so it’s like the tail end of the relationship, so I’m like, ‘you need to fucking get out, go get a job, go be something in the world — don’t disappoint me!’

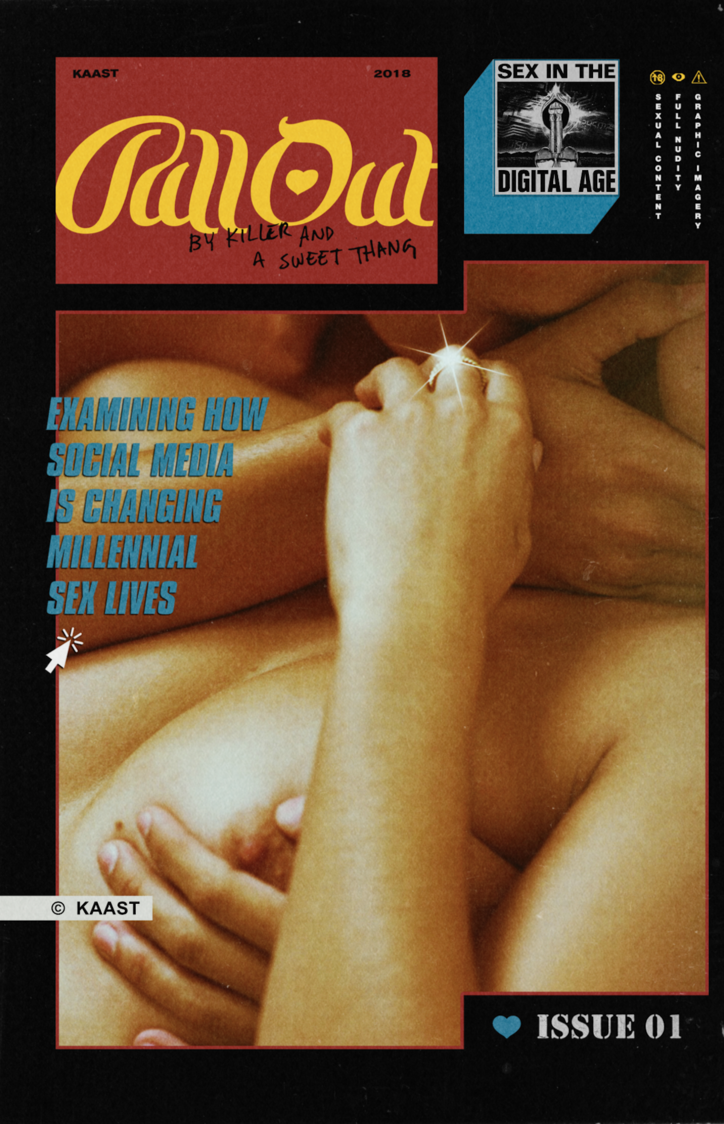

First things first, what does "Pull Out" mean in the context of technology and sex? Is there some rhetorical significance there?

In the context of sex, “pull out” refers to the contraceptive method many young people use as a replacement for condoms or birth control. In my research experience, mis/undereducation on safer sex practices is the cause of this dangerous alternative that too many from my generation turn to. Therefore, I saw “Pull Out” as a fitting title for a publication aiming to educate millennials on how to be more aware and as a result, hopefully lead safer sex lives. In the context of technology, “pulling out” is a reference to unplugging - from our devices, our phones and computers that constantly demand our attention. When you read a zine, hold a tangible object in your hands, you’re forced to set down your phone for a moment and truly engage with what’s in front of you.

This is your first print project, what prompted you to make that jump?

In this “age of the Internet”, the majority of our lives exist online. Print publications feel increasingly forgotten; there’s an element of mysticism in creating an object that functions outside of our tech-obsessed world. My career is a product of the Internet and social media, so of course I recognize it’s benefits, but I felt inclined to make something separate - a piece I could keep on a bookshelf, for example. It’s 64 pages, so it was definitely a bit ambitious for a first go...but I think it turned out great, and I’m really excited to share it with the world.

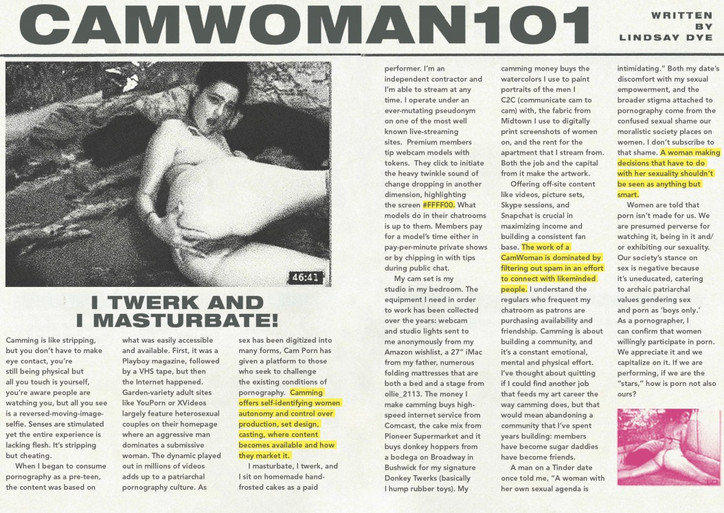

So "Pull Out" explores the dynamic of sex and technology. How the evolution of this specific dynamic relate to the larger ways we are re-learning our interactions (platonically, professionally, culturally)? Do they mirror each other? Feed off each other?

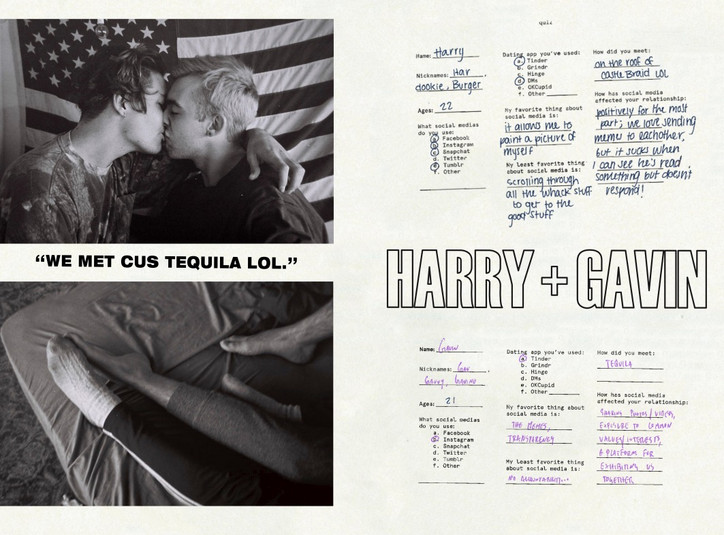

I think completely so. Technology influences how we interpret information; in the past, we were forced to interact mainly via phone calls or in person encounters, leaving less room for misinterpretation. With smartphones, we're constantly plugged in and have access to limitless people/communication; the majority of these conversations happen in written form, which forces us to read the “emotions” behind texts, emails, social media comments, et cetera. The human element can be completely lost. We don’t hear their voice, see their mannerisms, understand the emotion underneath the words. So whether romantic or professional, there’s always an ambiguity in our online interactions because of this emotional distance, yet there’s an immediacy granted to us because of technology and a constant ability to “connect” that’s lacking crucial information.

You've curated an impressive set of young talented contributors: Natalie Yang, ONDINE VIÑAO!!, Chella Man, Luke Gilford et al. What was that process like?

Thank you! It was surprisingly organic. I reached out to people I knew (both online and in real life) and asked if they were interested in contributing a piece - it was really a group effort. I think what’s special about this project is that everyone involved was able to run with the prompt in a very personal way. I wanted to see what sex and social media meant to them, to the people living this cultural shift. Everyone has a story to tell, and I am privileged to have this platform, so it was exciting to piece together all these different views/opinions and share them with the greater audience. This project took a while to finish, so big shout out to everyone involved for their patience.

Not that answering anything is the point of art, but after creating and then digesting what have you translated from this piece of work. Where has it left you in the question of sex and technology?

I’m constantly thinking about what’s next…what will social media look like in 5 years? What will our phones look like in 10 years? Who could’ve predicted that we’d be unlocking our phones by holding our face to the screen or have self-driving cars? Things are moving at a rapid pace; I’m excited and nervous to see the effects they have on the way we communicate and relate to one another. I think the porn industry is about to have some major shifts and that’s something I’ll be watching out for. And how many of us are going to tell our kids “mom and dad met on Tinder!”

Tell us about the launch party! What do you have planned?

There’s no better way to celebrate than to dance! I wanted to take the opportunity to gather all the contributors together with my friends and family. This has been such a group effort and I wanted to take a moment to thank and party with all those involved.

Could there be a "Pull Out" Part Two?

Maybe one day! But I’m definitely not rushing into creating another one anytime soon.

'Pull Out' releases today, and can be purchased here.

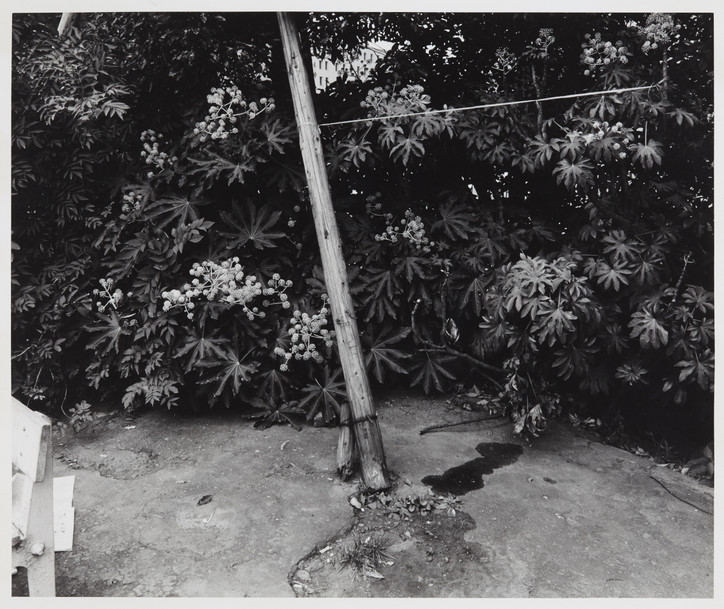

Though one might find more audacious articulation in his bondage photographs, this series remains a compelling thread in his calm-before-the-storm snapshots of Tokyo in the early 80s, where streamlined concrete casually clashes with lush greenery, the living, breathing background of an artistically observed life— one peppered with reclining nudes, (his first foray into the provocative), a wife facing a bleak diagnosis, and Araki’s most consistent muse: Chiro, his pet cat.

You will have to visit the gallery to get your uncensored Araki fix; but for a quick palate prep in the meantime, check out office's exclusive Araki feature from issue 07: Blue Period / Last Summer.