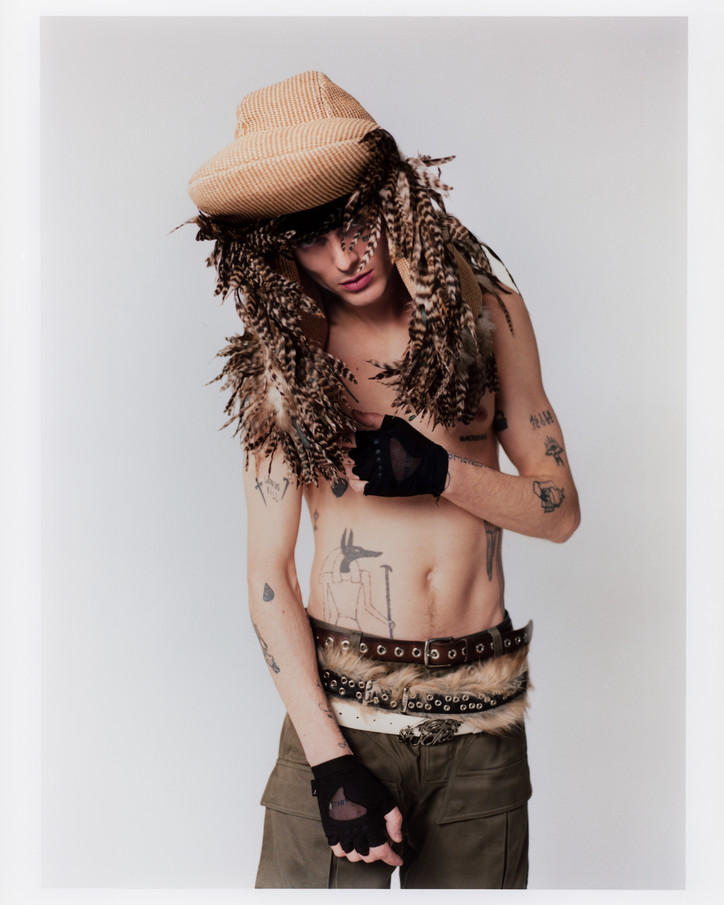

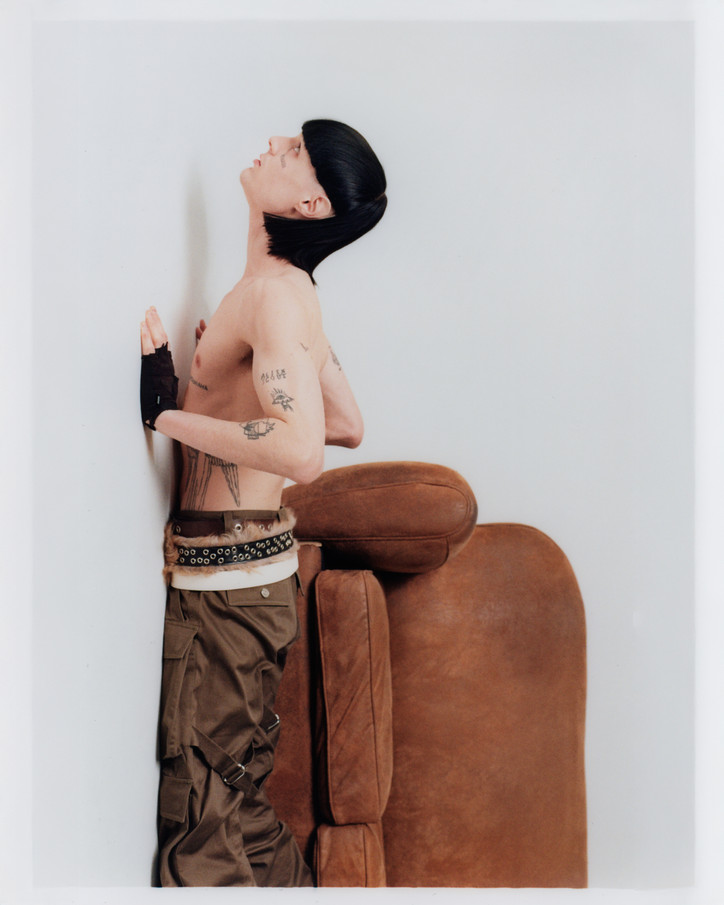

(RIGHT: TOP & SHORTS, Loewe LONG SLEEVE, ROA SCARF & SHOES, Ann Demeulemeester GLOVES, Puma JEANS, Egon Lab) (LEFT: TOP, PANTS, SCARF & BOOTS, Kiko Kostadinov COAT, Ariuna GLOVES, Sf 1 OG)

What was it like when you first arrived in Los Angeles?

It was surreal. It felt like everything was a movie set. The context was so luxurious, it was very strange. I was in West Hollywood, Fairfax. That’s where Hedi had his Saint Laurent studio. I was deep in my problems, really struggling. I was trying to make music. I was smoking a lot of weed, driving around, eating tacos… living in a kind of glamorous, nightmarish loop. I was feeling really terrible. But I still had some kind of fantasy about LA.

What was it like to return to Paris after living in these different cities and things changing in your life along the way?

Not comforting. It was time for me to return and to come to terms with where I come from. It was a challenge, I had to find my place there, a city that had never felt very supportive. It took a few years but now I feel like I have my role here, this is where I’m supposed to be right now.

What is the music scene like in Paris? I'm fairly involved in fashion, art, design, but music lesser so.

I don’t think there is much of a music scene in Paris like there used to be. 10 years ago there was a big scene of live bands, an indie rock revival. Today artists are more isolated. But recently there have been a lot of artists moving to Paris. I do feel like there is something developing here right now.

Live music seems to have fallen off in New York for sure in the last maybe 10–15 years. Would you agree? Do you see that in other cities as well?

Yeah, I think that’s because of social media and also the cost and complexity of producing live shows. People are entertained on the phone so there is less need to go out, so there is less support for live artists, but long term I think that will change. It’s depressing to be too connected to the internet for too many years. I think people need real life experiences, real connection. And music is one of the most powerful ways to bring people together. It’s a ritual.

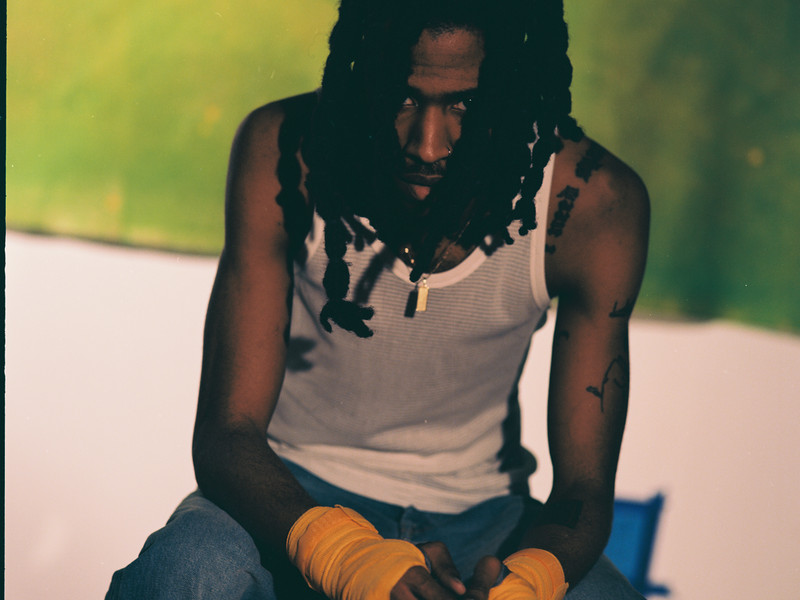

How do you want to be perceived visually? Your persona, how would you describe it?

I don’t want to be perceived in any particular way. I just want to live my lifestyle in a way that feels inspiring. My aesthetic is one thing, I think a lot of people assume things about me that aren’t true because of it. But I’m not gonna change to make it easier for people to understand me. I’m not one dimensional, I got a complex story, my life hasn’t been simple. So that shows in how I present myself, and that’s real. Evil for good. I let people figure out what that means.

Your upcoming album REV carries themes of revolution, revenge, and revelation. How do these relate to your personal life?

Revolution has always been relevant in my life. I never fit in to what society expected me to be, I’ve always gone against the rules because I had no other choice, I wasn’t meant to follow them. Sometimes I wish I could have, it would have been easier. But it just didn’t work like that for me, it’s like I was put on this earth to disrupt. I can’t avoid being who I am. Revenge is an energy, a powerful source of drive. I do want revenge, I want revenge for all the years I spent suffering, for the time I lost caught into endless cycles of mental and physical pain. I can’t accept that. I want revenge on the people that let me down. I want them to see that I made it, that their lack of belief or animosity didn’t stop me. I know revenge is dangerous, it can turn against me. That is one of the main narratives of REV. Revelation, because there is something bigger, something spiritual, that I can’t deny. It comes through sometimes to remind me, to give the keys, to make it all make sense. Those moments are rare and precious. Sometimes they come to me in dreams, sometimes it’s more conscious.

There’s a strong sense of mythology and world-building in REV. How did you craft this world, and what does it represent to you?

It represents my life. It’s an allegory for everything, from the city I live in to the industry I am part of, the relationships I have experienced. It’s a way to tell my story. I found that using fiction and allegory allowed me to be more truthful in a way. The world of REV is something that imposed itself, it was impossible to make it anything else. I think artists often have the experience that what they create is coming through them, channeled from somewhere. The world of this album was created like that.

The album’s sonic palette is more aggressive than previous works, blending post-punk, electronic, rap, and even witch house influences. What drew you toward this more intense, cinematic sound?

REV is an energy, a mindset. You can be rev, and that means that you don’t let anything stop you. The sound of the album needed to reflect that energy, needed to create an immersive world where the listener can enter into the story, become their own protagonist. The sound is intense and cinematic, but it has a range of opposite extremes that create a lot of depth and allow for the softer, soulful moments to shine through even brighter. I think that the aggression in the sound is something that takes getting used to, but once you get accustomed to it, you have learned the language of this world, you will understand what it means to be rev.