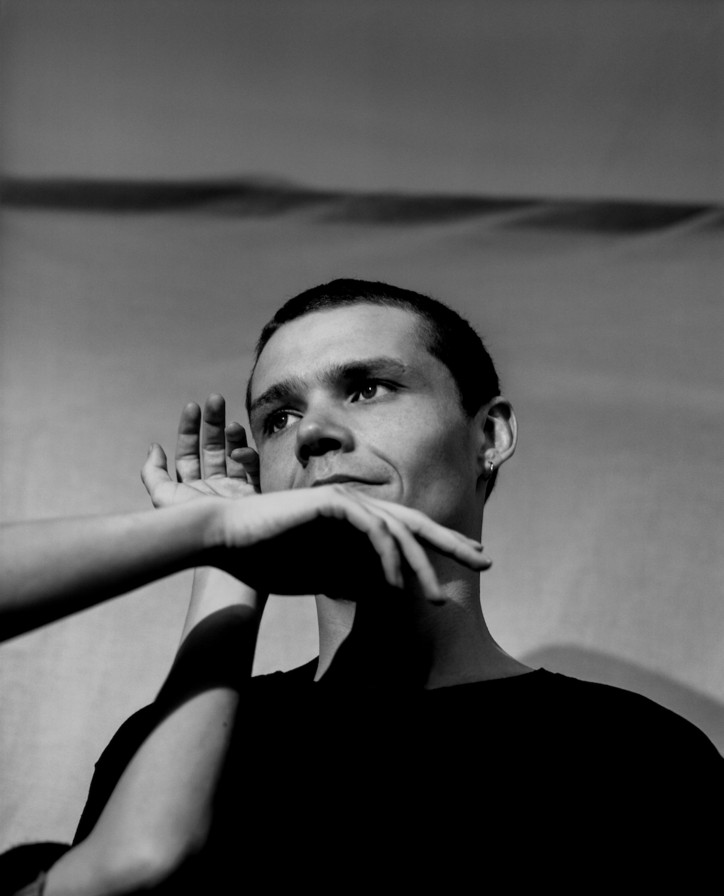

Westerman, Your Hero is Not Dead

Making a slight departure from his previous work which largely looked inward, he’s giving attention to the external on this album. “Blue Comanche,” for example, is nostalgically mournful and resigned about the effects of climate change, while the titular track, “Your Hero is Not Dead,” reassures that what hope was thought to be dead and gone “is only sleeping.”

Two years after his last interview with office, Westerman calls from quarantine in West London to talk about the questions his music poses and what he hopes to conjure out of his new album.

What have you been doing to pass the time in quarantine?

I've been watching a lot of films recently, which has been nice.

What kind of films have you been watching?

I've been watching old, classic films. My family is in all different places, but we've been doing these video calls, and we each pick a movie for everyone to watch then talk about in the evening. It's a nice thing. It's important to have routine at the moment. I struggle with routine, and it's even more difficult at the moment than normal.

What else have you been doing to establish a routine?

The last week I've gotten better about getting up in the morning and going for a walk, because we're still allowed to do that here, which is nice. Just going on quite a long walk, like a two-hour walk. It's really easy to just sit around doing nothing, but I find if I get out of the house, it clears my head a bit, and it's easier to come back and put my mind to things. I've been finding it really difficult to concentrate, as I'm sure a lot of people have been.

It can be very hard to sit down and be productive right now, even though we have all this free time.

It's unprecedented what's going on, so I've been trying this past week to just be kinder to myself. I spent the first two weeks not really doing much and being annoyed with myself about not doing anything. It's a very anxious time, and everyone is worried about their loved-ones. Nobody knows really what's going on. So it's important to cut yourself a bit of slack. I have a housemate, which I'm pretty thankful for.

You've said before that what's interesting to you about story-telling isn't necessarily the stories themselves but the mutual connection that comes from people's understanding of what's being conjured by the story. So what are you hoping to conjure on this album?

I wanted to make a record that felt optimistic. I've been asked before who I'm writing the music for, and I think ultimately I'm writing it for myself as a sort of therapeutic tool. But I hope that from that process once it's finished, it's something that can help soothe other people. It comes from a place of isolation really. There's an element of loneliness. And I would like people to feel comforted and to feel less alone when they listen to music.

You've mentioned that you hope there is a kind of empathy that can be found in your music.

I think it's just trying to be human really. It's trying to get away from bravado or artifice and trying to show some positive—and some negative—of humanity. And I'm trying to do that in as unfiltered a way as possible, because I think that's helpful for people. It's helpful for me, anyway.

Why did you choose to title the album Your Hero is Not Dead?

The title is just something that was said in conversation. I can't remember if it was me or someone else who said it, but it just kept popping back into my head. I had this idea of how I wanted the arc of the record to be and what I wanted it to contain, and the title really encapsulates what I was trying to do.

How would you describe the arc of the album, and what did you want it to contain?

I wanted to make something that was ultimately hopeful, but I'm not someone who's impervious to things that are happening—difficult things, bad things that are happening externally. So there's struggle there. It's not a happy-clappy record. And that title is, well, concerned with morbidity. But ultimately, the inflection of it is optimistic.

It seems like you have a really philosophical approach to music. I'm guessing that's in part because you studied philosophy.

Yeah, I guess so. I don't really know what came first. There're a lot of questions in the music. I've always had that sort of mind, which is probably why I studied philosophy.

What kind of philosophy did you study?

Quite a broad range, but when I got specific, I really enjoyed studying Greek philosophy. Ethics are really what I'm interested in. I enjoyed very much studying systems of ethics that are applicable without the necessity for a deity.

Well, since you studied it, let's get a little philosophical. Do you feel that there is a role for ethics or other philosophical teachings in music?

Yeah, I think as much as there is in anything anyone is doing. I don't think there's anything intrinsic about music which has to be ethical. But I think you can definitely make music for the right or wrong reasons. So there's that, I suppose.

What would be the wrong reasons for making music?

That's a really difficult question; it's gonna trip me up. From my personal perspective, I think the wrong reasons to make music would be because you expect or think you're going to get something else from it. Obviously you can hope that won't happen. I'm not someone who would pretend to not care at all about how people receive my music, but that shouldn't be the motivator for making it. I don't think you should make music thinking about if people are going to like it or potentially buy it.

Why do you think music has value then?

I think art—true expression—is a communication tool, and it's how people sustain each other in a way that's sort of beyond the personal. It's an amazing thing that I haven't met you, but you've listened to my record, and you have an opinion of that now—that in some way, shape, or form you feel like you know who I am. And that's amazing, I think.

Like you said, your album isn’t a “happy-clappy” one. Why do you think we choose to listen to music that elicits negative responses from us, like sadness, grief, or anger?

‘Cause I think there's a cathartic element to it. I don't really listen to angry music, but I definitely used to… when I was younger and angrier. Whatever the tone of the music is, people connect with it, because it manages, in a sort of non-verbal way, to articulate a particular feeling which we all share. With good music or any sort of art really—if it's good—it gives a voice to something you wouldn't think to articulate yourself.

Alright, one more quasi-philosophical question for you. Do you think that a piece of music's expressiveness comes from the emotions of the composer or performer, or does it come from the felt emotions of the listener?

I think it comes from the person who has made it. I'm thinking of the philosophical problem of a tree falling in the woods. Ultimately, you don't know—I mean you suspect—but you don't really know that anyone's going to hear what you've made. I mean I hope this doesn't happen, but if everybody was to disappear, and I was the only person in the world, if I made music, it would still be the same music. For me, this is a very interesting question. You've got me thinking about it in all sorts of different ways. But ultimately, I think the emotion comes from those who made the music, and that can be reciprocated—or not—by the listener.

You've described composing as a process of elimination, a whittling-down. That implies that you start with an excess. So, I'm curious about what the beginning part of your composition process is like.

Normally I would have a central, melodic phrase—maybe with a lyric, but often not. And then, once you have that, you have the first piece, but all the other pieces are blank, which is exciting but also frustrating. So it's a process of elimination in that you try lots of different things until it seems to sit where it should. It's a slightly intangible thing. It basically has to be felt, I think. Obviously, you can write music incorrectly from a formal perspective, but the sort of music that I make can't really be wrong. It's just getting it to the point where it feels right. I think a lot of it is balance. I definitely write more words than you hear. I'll write without thinking too much about it. I'll look at it and try to pinpoint what it is I'm trying to articulate. Then it's just a process of doing that in the most economical way.

Where did you learn how to write music?

I did study music up until I was fifteen, but I was never really excited by formal music. I think it just seemed quite dry. It felt a bit lifeless, really. I think I mostly taught myself by listening and learning from music that I liked.

You said earlier that there are a lot of questions in your music. What are some of those questions?

Am I doing the right thing? It's all inversions and variations on that. I think the questions are a kind of expulsion and get the things out of my head. There's something that's quite soothing about that. A lot of questions in my music don't really have any clear-cut answers, which is fine. That’s just part of being a thinking human being. Maybe that's something that people associate with as well. I don't think I'm the only one sitting around wondering what's going on.

I would hope not. I would hope we're all wondering what the fuck's going on right now.

[Laughs] Yeah, exactly!

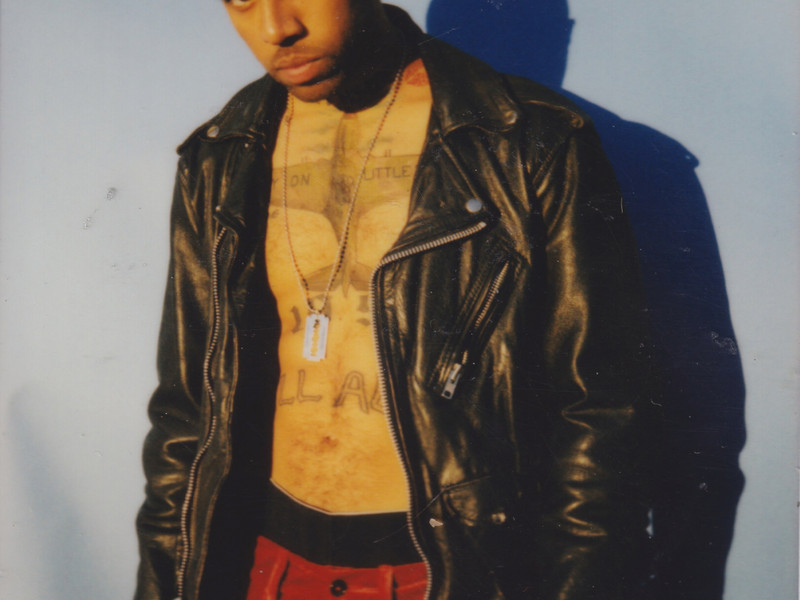

So you had quite long hair at one point. Why'd you cut it?

I cut it for two reasons. One, I was feeling that I really wasn't doing anything useful for anyone, and I raised money for charity. And the other one was that I thought I hid behind my hair a lot, and I thought it would make me have to engage more and be braver if I got rid of all of it.

Did it?

Yeah it did, I think. I'd say so. I think it worked.

It's amazing that such a seemingly insignificant change to our physical appearance can have such a big effect on how we behave.

Definitely. The way people look—it doesn't have to be a vanity thing. People do have these sorts of mental pictures of themselves, and it's just good to challenge them every once and awhile.

What do you hope for the future?

I really hope this period of time allows everyone to think about how lucky we all are, normally, to have the liberties and freedoms we have—and to think about the ways that things can work better in our society. I think a situation like this is going to have massive ramifications for years and years, and I just hope people regroup in a positive way that's fair for everybody.