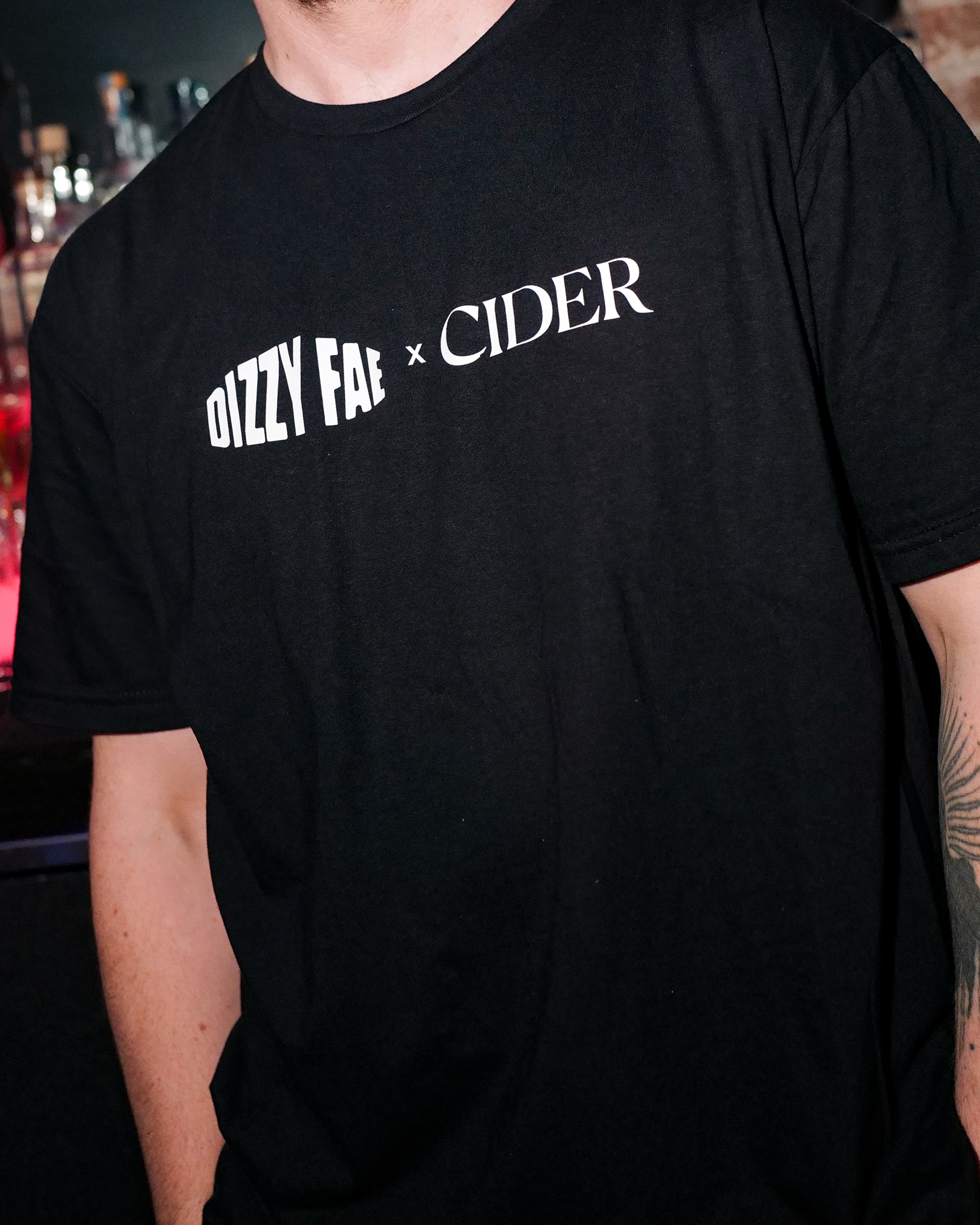

How did your collaboration with Cider come to life? What made this partnership feel like the perfect fit for you?

As an artist who weaves in and out of genres, embracing individuality is key for me. Partnering with Cider on this campaign was exciting because it celebrates the trends and aesthetics that define festival season and how we make them our own. When I was approached with the opportunity, I was ready to debut my new music and get back into performing, so the partnership felt like divine timing. Our shared value of authenticity made the collaboration even more special. Fashion is my way of expressing myself, and I love that I can base my outfits on my mood and go with what feels right.

What was your inspiration behind the Festival Capsule Collection, and how did you incorporate your personal style into it?

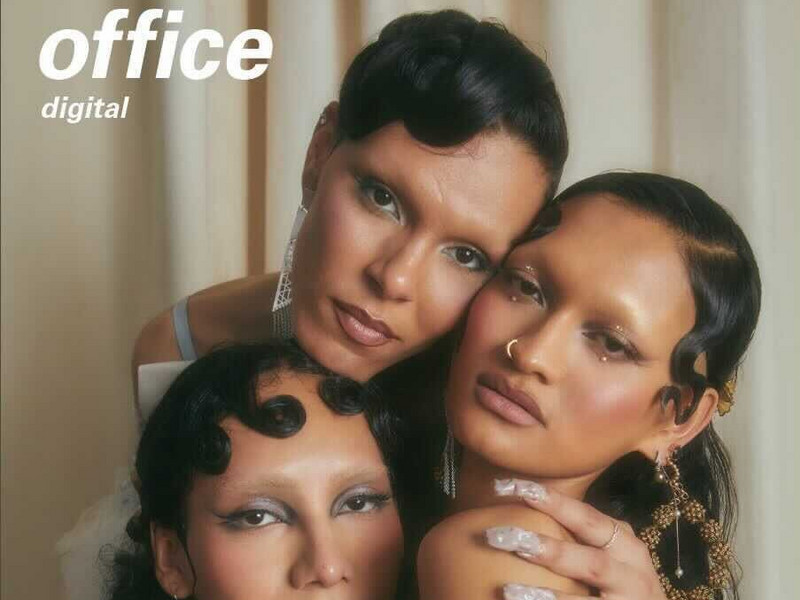

I’ve always seen my personal style as a fun, creative way to express myself — it shifts with my mood and evolves with me. I’m a mix of charming, cute, sexy, and playful, and Cider’s new Festival Capsule totally captures those vibes. The campaign highlights fresh looks for the season, with my personal flair like go-to hairstyles and, of course, my grills. It’s the perfect match for the creative energy that fuels my music!

What’s your go-to festival look?

My look needs to make me feel sexy and ready to move, no matter the weather. The capsule vibe is edgy and lets you switch up your look based on your mood, which is exactly how I love to style myself for performances.

If you could describe Cider’s new Festival Capsule Collaboration in 3 words, what would they be?

I’d describe it as cute, edgy, and fun.

What’s your favorite piece from Cider’s Festival Capsule Collaboration?

It’s difficult to choose, I honestly enjoy every piece in the capsule and how we put every look together. The Faux Leather Set might be a go-to for me this season though — super easy to dress up or down with bold accessories.