Amnesia Scanner Mourns for Mother Earth

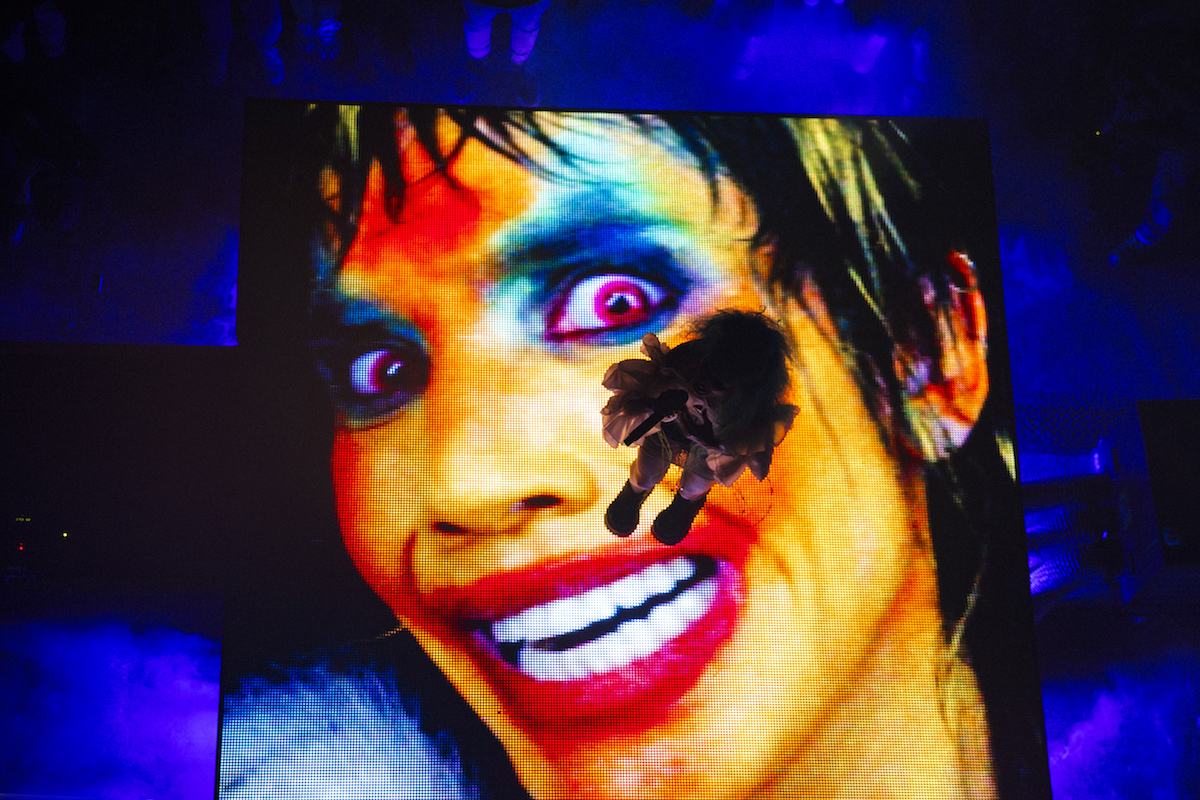

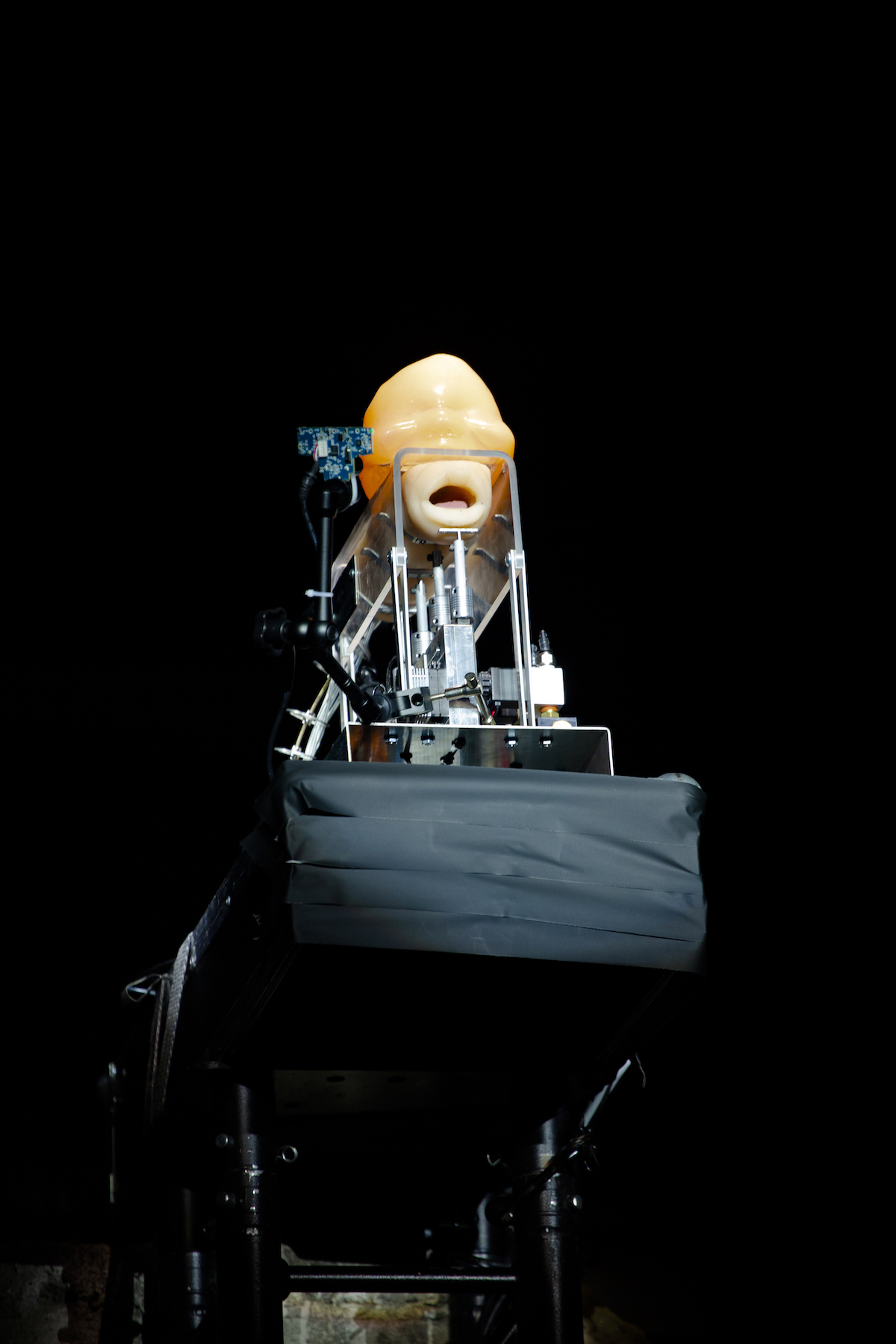

In addition to loving a strong concept, Amnesia Scanner seeks to weave their avant-garde sound into more popular structures that could be consumed more easily. Their performances have been described as ‘sensory overload,' with profuse usage of strobes, smoke, and noise.

Tearless is a step further in their transition from making abstraction-heavy “conceptronica” into creating more song-based, pop-ier music. Featuring artists such as the Peruvian model, artist, and musician Lalita and the Brazillian DJ and producer LYZZA, this genre bending LP will most definitely widen AS’s audience.

Congratulations on your second LP, Tearless!

Ville—Thank you!

Martti—Thanks!

Where are you two riding out quarantine?

V—It’s my first quarantine so I have no other reference point, but it’s been okay. It hasn’t been as extreme as it clearly was in other places, like I wouldn’t need to report to the police if I wanted to go to the grocery store.

M—I was actually in Finland for three months, I just came back to Berlin like a week ago, but it’s like an interesting experiment in location and independence I guess.

In the press release, Tearless is referred to as a ‘break-up letter with the planet’. What does this mean to you?

V—It’s more like a break-up album, and I guess it was more to play with the break-up album as a musical form… Everyone knows what a break-up album is. It was actually Martti’s colleague, Emily, who coined that term. It wasn’t written with that thought in mind, but that’s how it came out. The collection of songs sort of goes through very similar phases of emotions to the state of the world that you could go through when you’re going through a break-up.

M—Yeah, and an important distinction is we’re not the one leaving the planet. It’s maybe like the other way around. We’re kind of, like, mourning. It’s definitely not some nihilist statement that we’re transcending or leaving to Planet B.

V—Yeah, it’s more like, “Tell me what did I do wrong, take me back!”

What is it like to release music when you can’t perform it at one of your ‘sensory overload’ live shows?

V—I mean, it sucks. It’s always been a very significant part of what we do. A lot of things we do are kind of planned to be experienced in. So it feels a bit lame in a way, but it is what it is, I suppose. And then of course, still we could at least, in some limited form, offer these experiences, but no one really knows.

M—Amnesia Scanner started as a very net-native, or, like, internet-first project. But pretty quickly, the live part became kind of the most important aspect of it. It’s kind of sad; it is music to be experienced with other people. Fingers crossed that we can tour in the future.

What is the sensory excess and overload in your music and shows meant to accomplish?

M—The physical effects of stage technology, whether strobes or smoke, or being enveloped in smoke, it’s like being overwhelmed with sound and video.

V—Also composition wise, this sort of, like, the maximum emotion of EDM and genres like that, which are very exaggerated, and kind of bringing that from maybe a different angle.

M—We wanted for it to have a very accessible and physical aspect. They’re aspects you can appreciate intellectually or conceptually, but it’s not necessary to be that deep ‘in the know’ of Amnesia Scanner. We wanted it to be immediately…

V—Direct!

M—Yeah, exactly, direct. There’s this kind of crude, hallucinogenic aspect to smoke and strobes, and we’re definitely into playing with the actual physiological affects of that, too.

So, you want your music to have a physiological effect as well as being a listening experience.

M—Yeah, for sure.

V—It’s never been a very performer-led project, since we’ve always tried to draw ourselves more out of the picture and more, like, manipulate the room. So, then, to bring the energy into the room, you kind of need to charge the audience with all tools available, to boost that. And that’s super interesting, and I think that’s been very successful, as well. Even though the music can sometimes be more heavy, in sort of experimental circles, when we played in L.A., there was a mosh pit. That’s why we’re more interested that there’s an actual event when we play. It’s more like the togetherness of the audiences and us. It’s this kind of fugazi cliche that the audience is more important to the show than the music… the combo of provoking them to do something and that becomes the event.

I think it’s really interesting to have music that’s meant for performance. There’s music that you mostly want to listen to by yourself, and then there’s music that’s supported and improved by the atmosphere. In what ways do you think the nature of consuming music and live performance is changing?

V—It’s definitely much more through these things. *holds up iPhone* And that’s okay, but it’s funny how it’s definitely the main way of having a takeaway from the show is to have an Instagram story or whatever.

M—There are many aspects that are, like, wrong with streaming and the economics of it and, of course, one of the most important ones, the economics of artists and labels. But I think from a cultural point of view, this kind of removal or collapse of context is one of the most insidious… For instance, when you stream, things just appear without a context. They’re removed from their themes or geographic locations, or whatever the world is from which they came. Of course, music can be appreciated in itself, in isolation, but from the point of view of a healthy independent music culture, that’s super destructive. I hope that this is somehow becoming more visible, or that people understand it more. But I’m pretty pissed, I think music is going to become worse before it gets better.

So, just to clarify, you’re saying you think when things are consumed without any context it's detrimental to the art?

M—I think it’s detrimental to the art and to the artist. Their work just becomes content, and content is like mined for data. Often, like, things like albums don’t matter. When you release something from a label, the label is meaningful, it represents a scene… Things like Spotify want to completely remove the label from the plate. I think there’s just a lot of cultural knowledge and information that’s being lost, essentially. Live music… I’m pretty sure Covid isn’t helping. What we’ll have left is like LiveNation and a few other energy drink brands.

V—Maybe there’s a Spotify live that you can stream…

I’m actually going to a drive-in concert tomorrow, so that might be the future of live music.

M—Yeah, I think it’s like, cute and great that there’s all these, like, alternatives, but I also think it’s made it so clear that there are no alternatives to the real thing. You know, like, I haven’t heard of anyone going to a streaming rave recently… It was fun for like a week in March, but I think we all realized that that shit doesn’t work.

V—Also, the nonstop DJ live streams have faded out.

You’re well known in fashion circles. How did this come to be and what role does fashion play for you in your creative processes, if any?

V—I think it's quite natural. I mean we both kind of more or less also work in other fields. We aren’t only working in music. We also work with artists and in collaboration with friends who work in fashion and design. At least partly, I would just blame that fact. At least from my side, these natural connections have just been that I know people in these circles.

So it’s social?

M—Yeah I think for us, in particular, we’re mostly just socially connected, but in a more larger scale, there’s definitely this kind of convergence or encroachment of art and… I don’t know exactly how to describe this overlap between fashion, art, culture, content… This content industrial complex. Somehow it just fits into whatever kind of paradigm… We also make a lot of iconic t-shirts so in a sense we’re like a tiny, tiny, fashion brand ourselves.

Were you saying that there’s a convergence between fashion right now and your music?

M—I wanted to express it more without value judgement, but negatively, of course, the fashion industry is kind of mining these other adjacent cultural things for cultural capital, which has always happened. Now, contemporary art, which is also a world that we’re in, or like the fashion world, is looking at a lot of that.

V—And Instagram has technically kind of flattened all these different kinds of mediums, and you consume them right next to each other. You can just go through your stories, and it’s, like, from a fashion designer, to Amnesia Scanner, to a contemporary artist, and you can’t necessarily tell the difference anymore.

M—Yeah, that’s kind of what I meant by fashion, art, content, industrial complex, it’s like this flattening of culture into consumable bits. I mean, it does have a bit of a similar thing to streaming- not to such an extreme extent, but it’s also flattening contexts.

V—I guess why we are sort of in there is that there is a strong visual side of our project, what we’re creating together with these two designers called PWR Studio, so it’s kind of like, the project communicates a lot through image and we produce a lot of images. So, I guess that’s a big part of the reason why, then, somehow this overlap happens.

M—Just to conclude that part, I think a lot of the interest is coming from that world toward us, not the other way.

I was wondering if you could elaborate a little bit on how Tearless represents what it feels like to exist in the world right now. How did you translate that into sound?

V—In this case, maybe our process has been the most direct, so far. I think I’ve seen kind of wrong readings of that, where people are thinking of it as a kind of nihilist or even accelerationist statement, somewhat, but it's much more. I feel like the songs are written in actual fear and sorrow and confusion of our time, and also the complete bipolar, or I-don't-know-how-many-polar, way of existing in the current time. Just like a direct reaction to that. Of course our process, of how it’s written, the sound, and how it’s produced, also has a kind of corrosion to it that, I guess, keeps somehow trying to translate how it feels. But I think it’s much more direct in terms of what the songs are about. A lot of them are very sad and emotional and some songs are kind of in denial… like no, no, no, I just need to keep on going even though the walls are crumbling around me.

M—I’d say it’s more expressive than representing stuff. In a sense, it’s a more intuitive process rather than finding sounds or other things that represent ideas.

I was wondering about your moving away from abstraction? There’s more of a pop aspect to this project than your previous work.

V—This record is definitely sort of in the same continuum as the last album, which was already a step more toward structured, song-based (you could call it “pop-ier'') direction. And then this, again, is one step further. But some of the songs... ring as sort of a continuum of us. We just felt that we had come into some sort of end of what we could get excited about this more abstract collage-y work, and we both are big fans of and consume a lot of pop music and song-based music. So, it was interesting to see what happens if we take our quite out-there, sonic world and try to weave it into structures that wider audiences are more used to consuming. And it’s also a challenge. Without wanting to be too polemic, I think a lot of experimental music is very lazy, and I felt to take up the challenge that I want to write good songs. I’m not saying that I always did, but we are trying to learn that craft. I guess that’s been the process.

M—The live show has definitely been feeding this ambition because then once we start to play this stuff out, especially off the previous album, it turns out, surprise, surprise, it’s quite fun to play out and it works. That kind of positive feedback led us to work more in this pop idiom.

V—Since we wanted our live experience to be this inclusive moment of togetherness, then you kind of wanna make songs that you can sing along, or that you can have this more shared experience. I think in that way it’s definitely been successful because the touring has been super fun ever since we started doing that.

Can you talk about the closing track, "AS U Will Be Fine," and ending Tearless with the message that through all the collapse, we'll all be OK?

V—I don’t think it’s a conclusive statement. It’s more like a denial. Like, you can lose your mind, and maybe that makes you, on a personal level, feel that everything’s going to be alright. And, of course you want to believe that every individual will be fine.

M—Yeah, it’s almost like self assurance, rather than a mantra.