Compendium of Longing

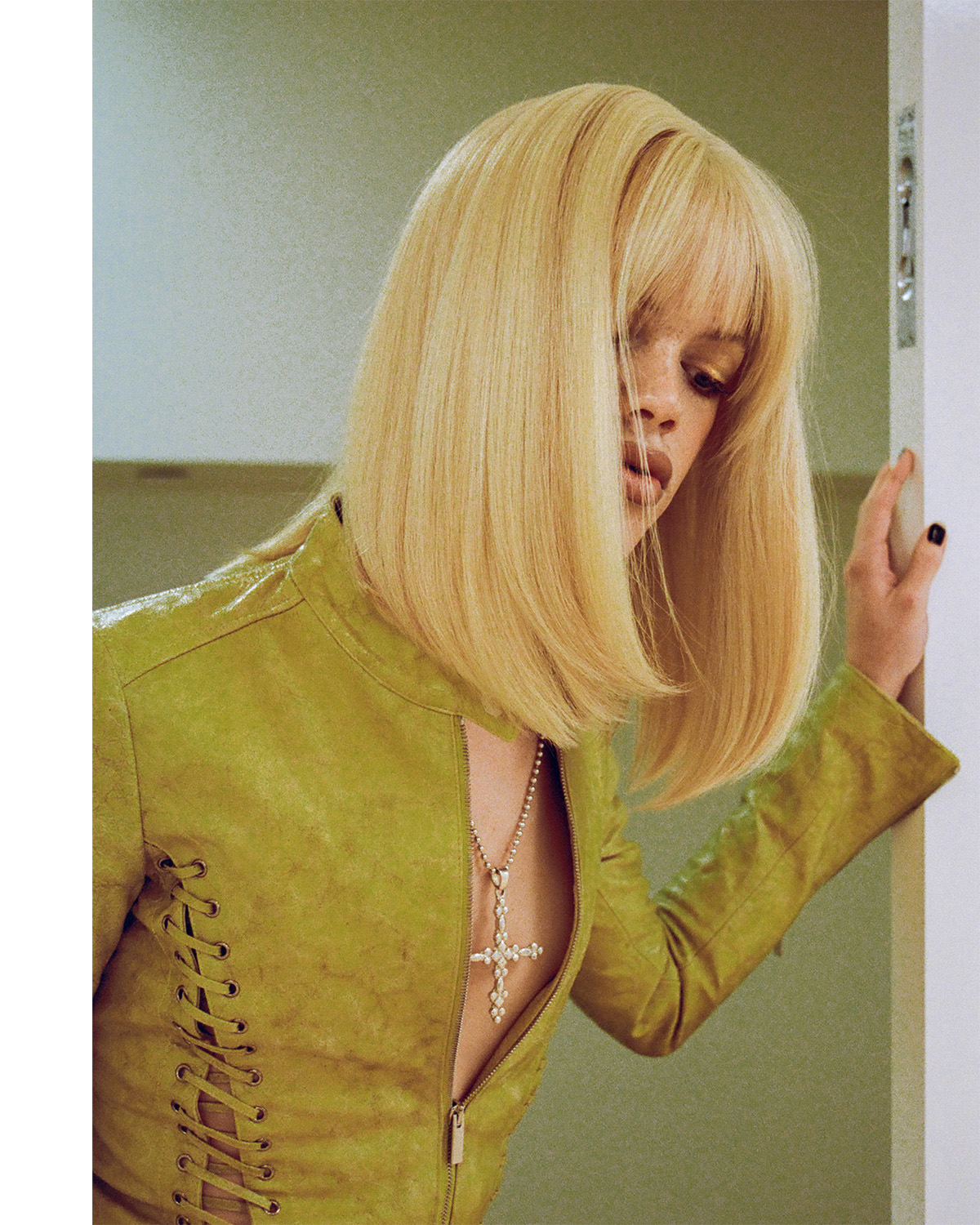

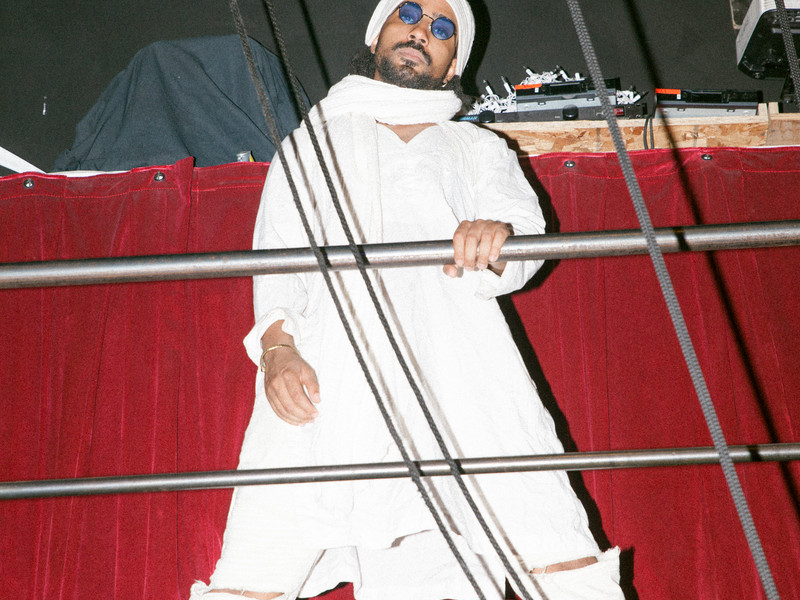

That much is immediately clear, at least musically. Tehran has never been easy to categorize, and the production on Dozakh weaves in and out of genres, tapping into punk, rap, indie pop, and R&B along the way. The album opens with Tehran singing in Farsi on the airy 'Dozakh', before transitioning to her heart-ache induced crooning on the synth-laden 'Down'. “I came up with Persian music from my parents,” she recalls, “then I went through the whole Spice Girls era, the Britney spears era, and then I went into punk music, The Smiths and Joy Division, and then I went into hip-hop, and so all of those styles will always affect the way that I work.”

This sonic palette lends itself to the breadth of feelings beneath the surface. Her confrontational attitude is still present on songs like the punk anthem 'Something New', or the acerbic percussive-rap track 'Jet', but most of the album opts for a more introspective approach—a plea to be understood. “I wasn't arguing with anyone in these songs, I wasn't telling anyone what they should think or what they should think of me, this was just a place where I can just deal with things from an emotional perspective.” Like 'Refugee' and 'Cash Flow', Tehran’s politics are still on full display here; there’s even a song called 'Nazi Killer' which succinctly captures her view toward the rise of the right wing in countries across the globe, including Sweden: “I think it's this idea that we have about ourselves that Sweden is such a neutral country, we're not racist, so the self-image doesn't go with what's actually happening. The winds are really blowing here, and people aren't taking it seriously." But more often she allows the underlying political framework to carry her message, without the need to define it explicitly. “I'm a political person, so I put [the songs] in a political context, but a lot of them are love songs, or songs about drinking too much, or dealing with mental health, or all these things that are a product of a political and structural problem and oppression.”

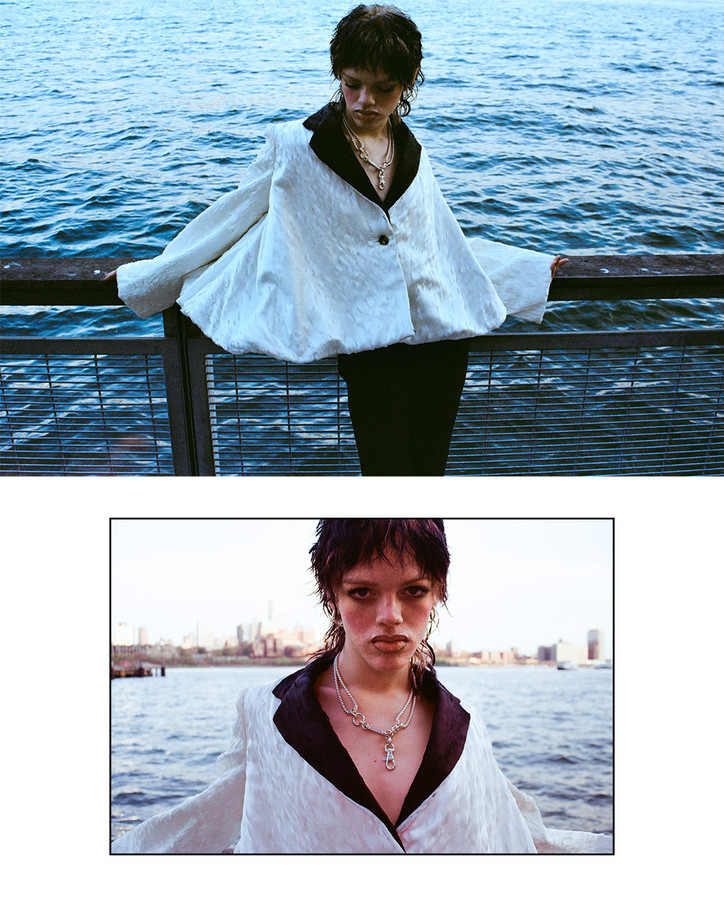

That’s the heart of Dozakh, and whether it’s prompted by political instability, heartbreak, or interpreting your place in society, displaced identity is the running theme. The word dozakh, which means hell, conveys a sense of longing, which has tugged at Tehran for the better part of her life. “It’s an emotional state that you're in when you're separated from your lover, so it's a very specific place that you are in,” she explains. “It's like a metaphorical place when you're burning in this longing for someone or something, so you're just there, you're in dozakh.” Tehran sees it as a universal idea, applicable regardless of a person’s relationships or background or cultural environment. “It’s a sense that something is missing and you don't know what it is, and the quest of finding it becomes a state of mind. I think I've always felt like I've existed in some kind of gap or a void or in a distance to something, and that's my interpretation of what dozakh meant to me.”

Though Tehran still feels that longing for something, she’s still largely optimistic in the midst of uncertainty, and Dozakh lays all of that out for her in a cathartic way. “I've had this heavy weight that I've been carrying and now that I can tell it to you, you can relate to it, and then it just becomes lighter for both of us, because we can find a unity if we start taking about it and sharing the emotions and sharing the experiences, we can grow stronger together and be there for each other.”

As she surrenders to her feelings on album closer 'In Tune With the Moon', there’s a sense that she’s ready to move forward, and with ten years of her life bottled in a bold, eclectic, and all-encompassing work, it begins to reveal the thing she’s yearned for all along: “That really is the core of why I make music, because it connects me to other people that share the same feeling. It gives me hope, and it gives me energy to try and make a change.”