Stay informed on our latest news!

Sign up for our newsletter

A Curator's Perspective: Alexander May Speaks With Spencer Daly

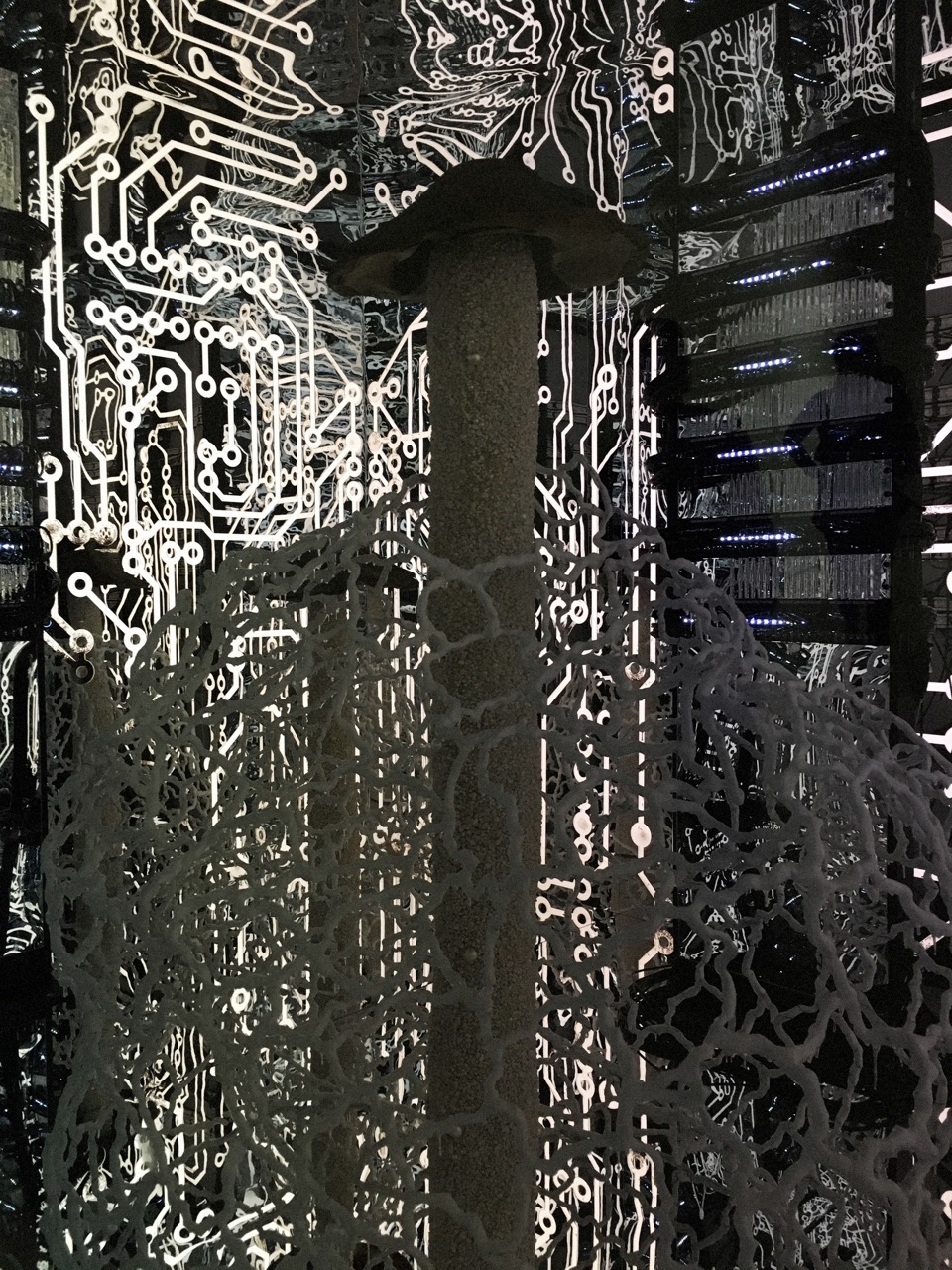

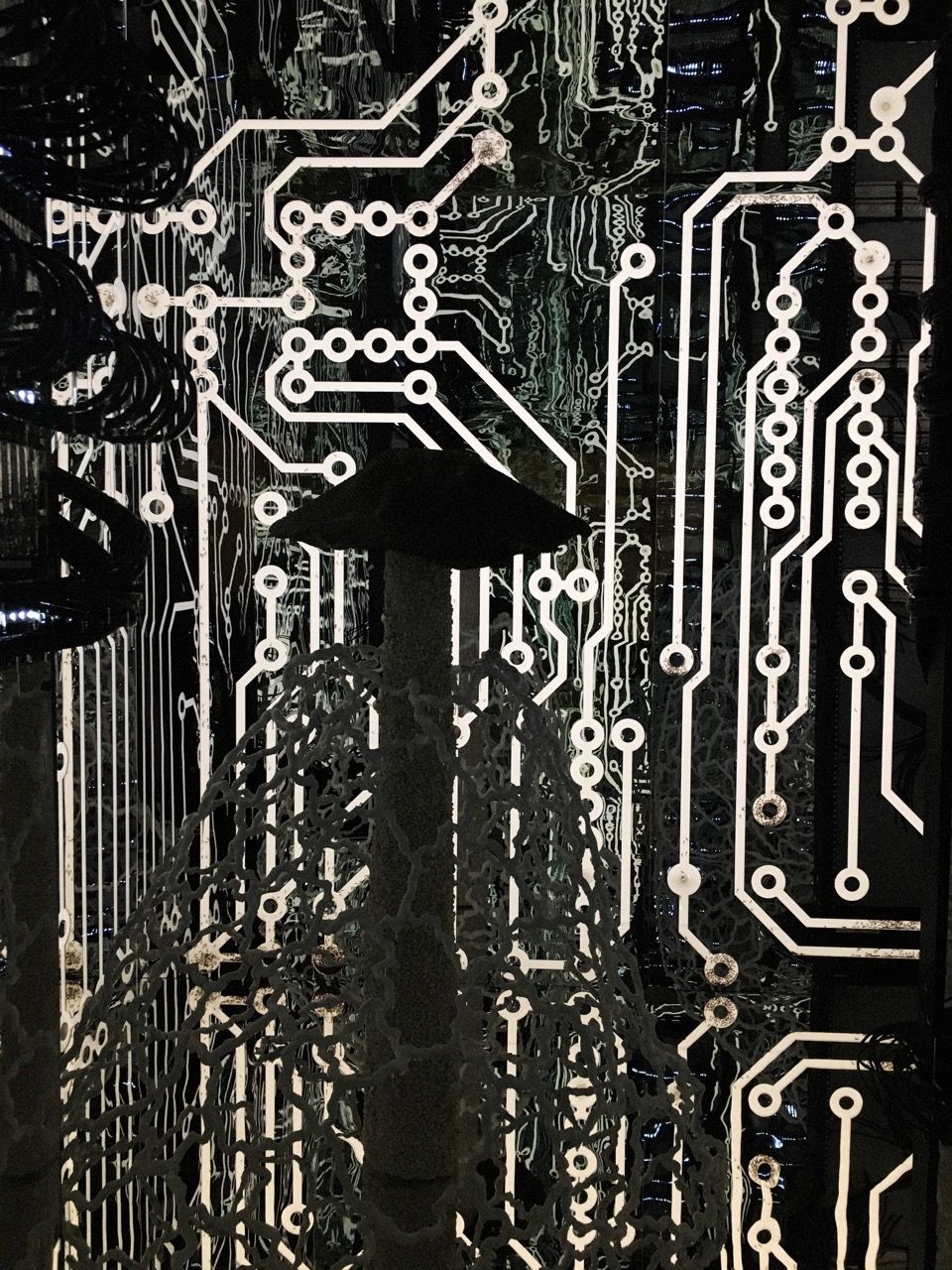

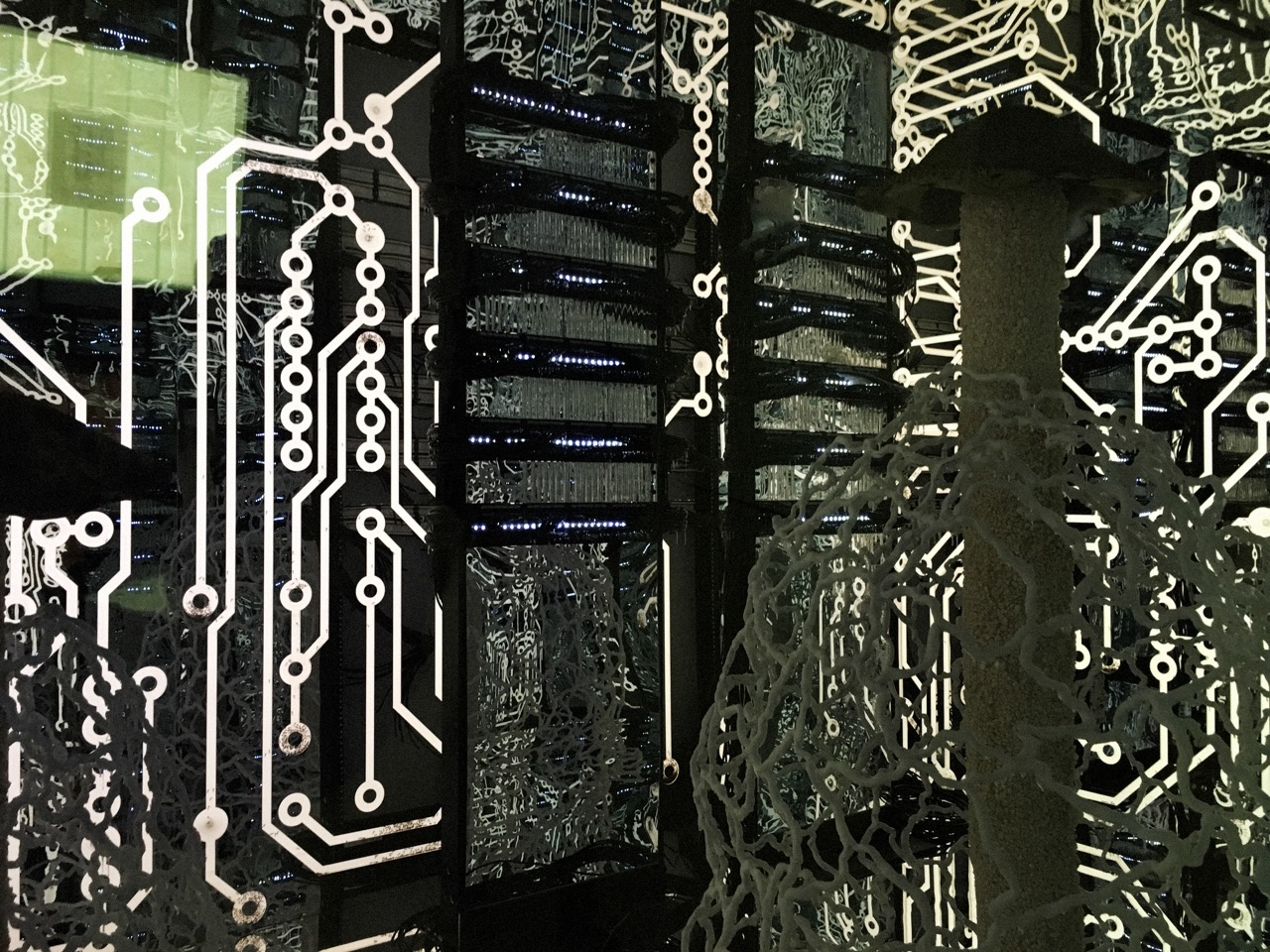

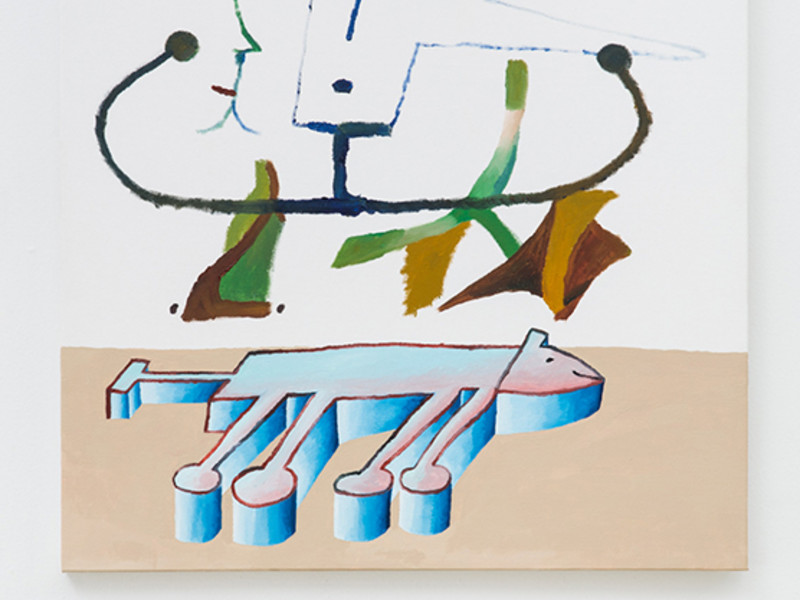

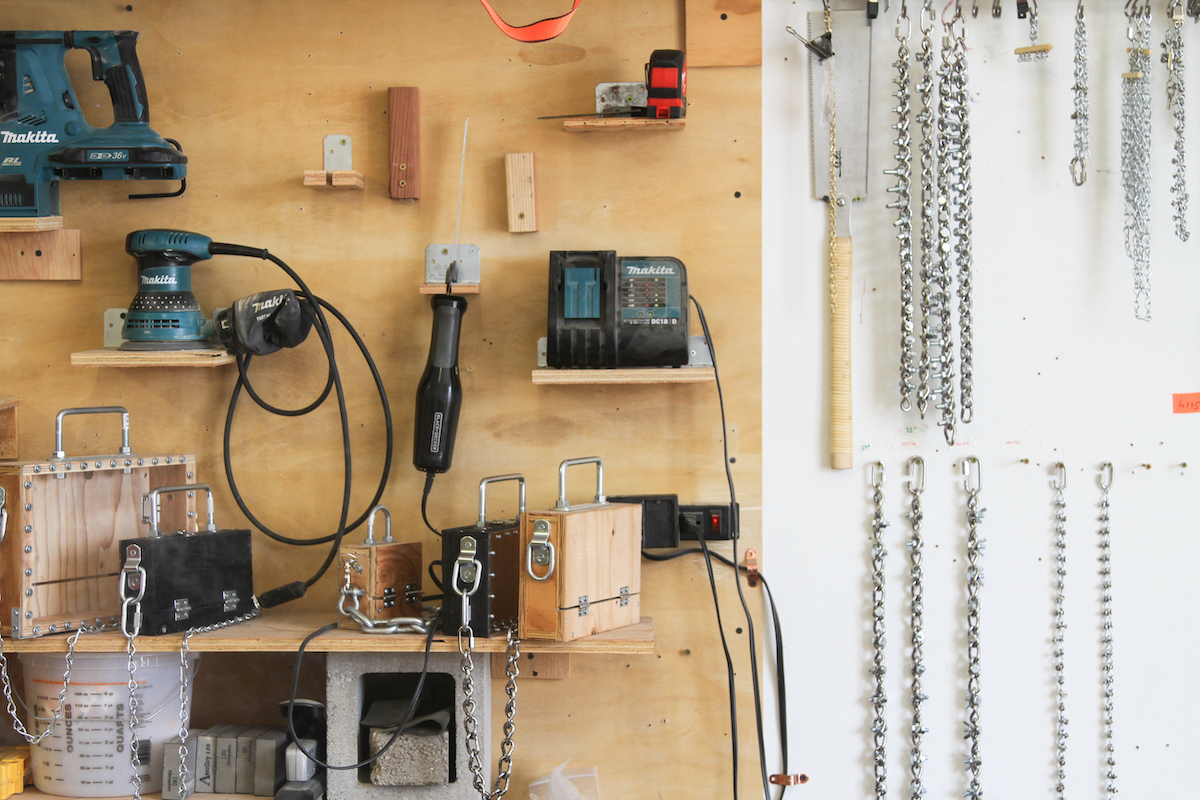

Among those on display, artist Spencer Daly makes everything with his hands. Repetition is central to his practice, screw after screw, like rosary bead after bead. Every movement sets the tone for the next, prolonging the initial intention until the moment of completion. After a while, the repetition becomes distorted, obsessive, almost disruptive, cultivating a sort of meditation around the work. Should he stop in the midst of this ritual, what he imagines may never exist. In light of the opening, May sat down with Daly to give us an exclusive look at a curator’s perspective and a glimpse into the mind of the artist.

Alexander May– So, is that all the pizza that you've ever eaten?

Spencer Daly– That’s some of the pizza I’ve eaten.

AM– There's like 40 boxes, right?

SD– The stack actually goes around and over my desk as well. I think there's closer to 100. I can't fit anymore so I have to throw them out now.

AM– And you were saying that they're connected to your first show right?

SD– When I did what I call my first show, a rogue trip to Paris during Men’s fashion week, I spent two months trying to figure out how to build and ship four chairs to a tiny Paris showroom in the Marais. I ended up taking each piece apart and flying with four suitcases. During this time, I was so focused on working that every day I ate the same lunch – a slice of Sicilian pepperoni pizza from Pizzanista down the street. But yes, this pizza is now forever linked with the taking apart, packing, and traveling with my work.

AM– It was really kind of like modularity.

SD– I hate modularity, the word, because I went to architecture school and that was a kind of architectural masturbation. Modular is a little too clean for me. It makes too much sense. I see my work more as singular – objects that can’t be split.

AM– So you wanted your work to be able to travel essentially. That's how you’re connecting these different materials and utilizing that as a structural basis to make form in a way.

Do you think about ornamentation? Like with the abundance of detail in the new cabinet piece? There's not one or two locks, but fifteen. There is a lot of that in your work – you polarize something and then expand it until it becomes almost like a texture.

SD– That's a symptom of obsession for me. When I find something that feels really good, I do it alot – like pizza. When I drill a screw 1000 times, the act of labor becomes a sort of ritual that turns into meditation.

AM– That sense of repetition gives you the support or structure that you're looking for to figure yourself out along with the piece. It's like completing a rosary, the repetition with the beads creates faith in something.

SD– A certain amount of screwing and bolting creates a sort of religion around the work. Construction is a primitive act. For me I’m trying to return to the hand and mind and soul relationship through the act of labor.

AM– What do you think repetition does for you? It seems like you aestheticize repetition? That's something that's really interesting to me about your work. You're compounding on the baseline of what an object needs. What are some of your influences in that way?

SD– Construction sites are where I mostly find influence.

I also think repetition, at least to the degree that I do it, starts to prove a point. To repeat an act, even a very simple act like screwing a nail, when done 1000 times, gets challenging mentally. Repetition in my pieces helps me understand my limits mentally, physically, and spiritually.

AM– I think the essence of your work very much implies the body, there’s this use factor – where the body comes in or is activated. Aside from preparing and imagining any of the pieces, you’re also involved with screwing all these pieces together, locking all the locks, etc. I find it a subversive way of pushing the figure into the design.

SD– When I was younger I spent some time with Larry Bell who told me that he never made a piece that he couldn’t build alone – meaning that one single piece of material could never be too large for him to carry alone and one single piece could never be too ambitious for him to build.

My work follows a version of this. My body, my ability, my stamina determines the scale and the detail of the work. If I can’t screw in 1000 screws, then the piece won't get done. I have to be ready and willing and capable of constructing each piece I imagine. So my work, right now, represents the strength of my body.

Repetition in my pieces helps me understand my limits mentally, physically, and spiritually.

AM– That’s a nice way to think because you’re more brutalist in a sense of the way you are working with your hands, which is what I’m much more interested in nowadays.

There’s been a movement towards handmade and handicraft, but what’s really subversive and interesting about your work, and what drew me in initially, is that I found it polarizing. I didn’t quite know where to place it. Your work actually requires a lot of the hand because so much of it requires these manual movements.

SD– My work wants to be touched, and I think if something is going to be touched, I want an act of reflection to go along with it. For example, some of my pieces appear uninviting to a sitter, but inviting enough to be curious. This betweenness might make someone hesitate and consider sitting in a way that they haven’t before.

AM– You basically insert an intention and you become aware of the intention by doing the most basic form of action, like opening a cabinet, but once that position is repeated, that’s when things get a little strange, and kind of exciting.

SD– I just want the user to get the same feeling in opening that cabinet that I had while constructing it. It is my way of sharing my ritual.

Recommended articles

An Inside Look at Manifesto

Paige Silveria— Tell me about Manifesto: this iteration and past.

Alessio Ascari— This is the third year, third edition. The first, back in 2019, took place at Lafayette Anticipation—an OMA-designed building in the heart of Marais. It was a great success, and I hold it very dear because the centerpiece was an incredible sound sculpture by Virgil [Abloh]. But then Covid happened and the project was postponed and then canceled in 2020 and 2021. Last year, we partnered with online platform GOAT to bring it back. We chose this incredible building, the headquarters of the French Communist Party designed by legendary Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer, which is just a dream. In Paris, it feels a bit disconnected from the architectural context—in a cool way. And Manifesto similarly, is like a UFO landing at Paris Fashion Week once a year. We see the festival as a live manifestation of the print magazine in the physical space. The way we curate the event is akin to how we build editorial content, and the programming is a similar combination of music, fashion, and art.

The programming you create at your space in Milan, Spazio Maiocchi, it’s at the nexus of culture in Italy. And here with Manifesto, you’re similarly creating something pivotal. How would you compare activating in each city?

Milan is a smaller city; it’s exciting and dynamic for such a small city. Paris is much bigger and the community is more global and diverse. Initially we were a little ambivalent about organizing the festival during Fashion Week as the calendar is so packed and people are so busy. But the reaction has been enthusiastic, and because it’s a public event we bring together a really unique mix of fashion industry leaders and local creative kids.

You’ve been working in magazines for some time now. You left art school early to pursue this?

I studied philosophy and visual arts. I wasn’t a good student, and during the first year in university I started working on my first editorial project; it took off in the art world in Italy and then Europe, and became a job for me very quickly. So I dropped out of school and started doing that full time. That was over 17 years ago.

How did Kaleidoscope come about?

We started as a hardcore contemporary art magazine. That’s our background, and my background personally. Then after the first few years, we started feeling that the art world was more and more isolated, and not entirely in touch with where visual culture was going. We felt the urgency to open up to different creative fields, different scenes, different areas of culture. It’s also a personal journey that we followed organically. Now the magazine is more and more hybrid, but even if we do a lot of fashion—and with our sibling publication, Capsule, we cover design, architecture and interiors—we still look at things from the angle of contemporary art. Coming from that foundation, we have an experimental take on things that is still our signature. For me, the most inspiring thing is collaborating with artists. That’s the thing I enjoy the most. Artists—and by that I mean musicians, creatives of all kinds—are the truth-tellers. They’re ahead of their time. You look at art, and if it’s good art, you can feel a vision about the future. That’s what keeps me inspired.

That’s the thing I enjoy the most. Artists — and by that I mean musicians, creatives of all kinds — are the truth-tellers.

Your projects are continually expanding. Can you delve into this a bit?

Kaleidoscope is almost 15 years old now, so more like a teenager. I used to be very closely involved on a daily basis, but now we have a bigger team and I let it go a little. Capsule is the newborn, only two years old, and it’s a new vibe. Like it often happens with siblings, they have very different personalities: Kaleidoscope is more experimental, weird, dark. Capsule is more minimal, pop, positive. It reflects a different industry and has a small dedicated team. Similar to Manifesto for KALEIDOSCOPE, in Milan during Design Week we initiated an event called Capsule Plaza—in between a fair and a group exhibition, bringing design, fashion, tech, beauty, together under one roof. The way we work is that around each magazine, we create an ecosystem.

But the magazine is still paramount?

The magazine is the laboratory. Once or twice a year—Capsule is annual, Kaleidoscope is biannual—you regroup with your team, cook all the ideas that you collected, engage with a variety of creators and contributors. For me, every time that one of my magazines drops, it’s like updating my operating system. Boom, refresh. New ideas, new outfits. I started doing this before Instagram, when magazines were the social network. You used to read them to learn what’s going on in London, Tokyo, New York. They reflected the scenes and the subcultures. Now we’re all connected, and the landscape is global. It’s a totally different scenario. Still, it can be hard to stay in touch and not get lost. Magazines stay relevant because they’re still a great way to present ideas and build a community.

Recommended articles

Nick Thomm: Endless Aurora

Inspired by the vibrant energy in Las Vegas, Endless Aurora captures the eclectic energy of the city in one hypnotic piece. His hallucinatory style is reminiscent of a psychedelic trip gone right, the sort of thing you could just sit and look at for hours.

Through trial and error, and with the right ambient music to set the tone, Thomm experiments with new techniques and mediums for each piece. For the Louis Vuitton commission, Thomm worked with acrylic, ink, and resin, layering vibrant hues against darker colors, inviting viewers into a portal of color and emotion.

Thomm’s work has previously been exhibited internationally, including the New Museum in New York, the Moco Museum in Barcelona, and the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne. He also commissioned works across the UK “Live” sites during the Olympics as well as a three story video wall on Oxford Street, London with W1 Curates. Even Miley Cyrus tapped the Australian artist to commission a large scale mural for her LA home.