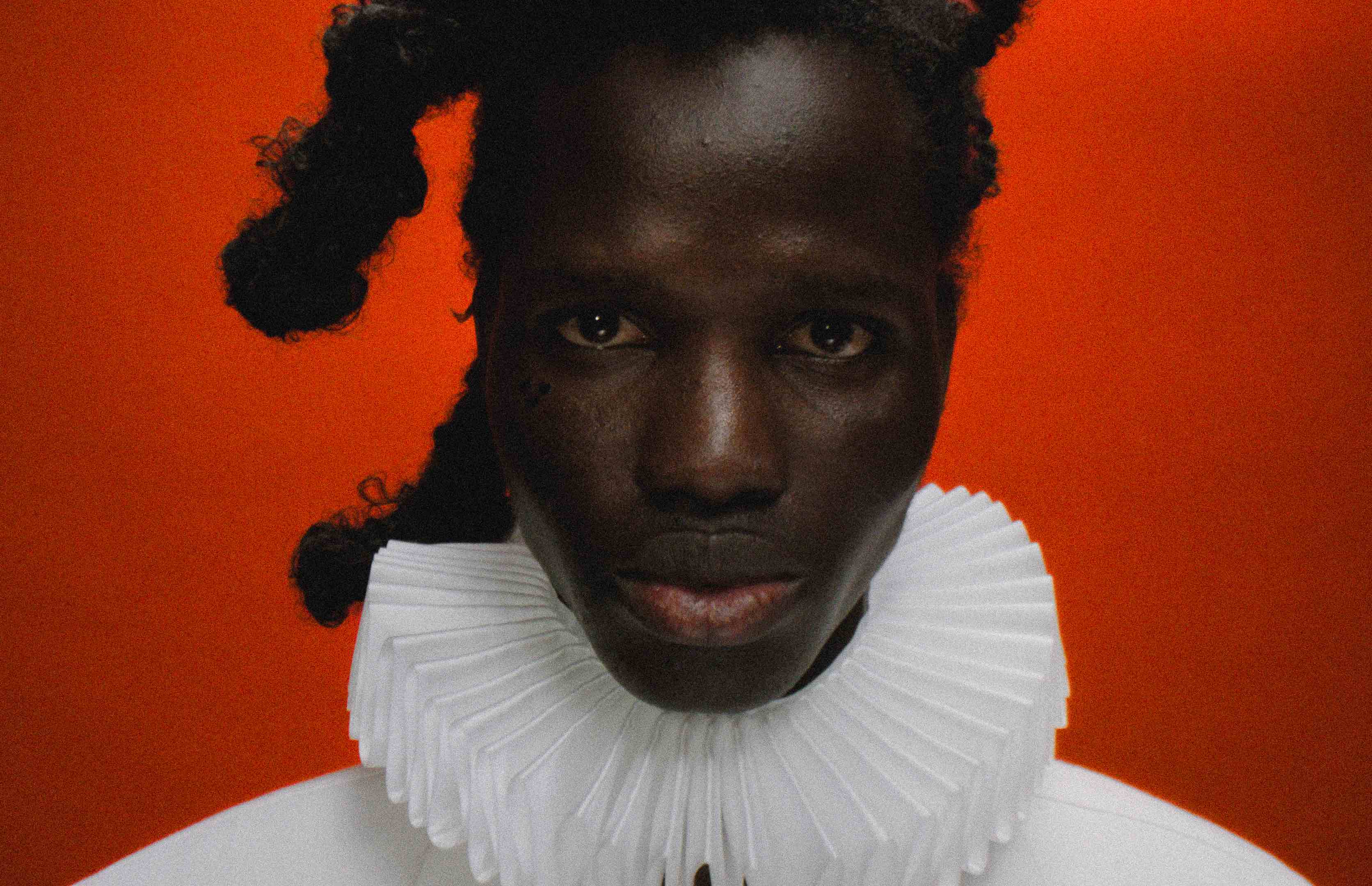

Atelier E.B.'s 'Big Tobacco'

Beca Lipscombe: We’re looking forward to seeing the collection come together, especially when Lucy's paintings are still in transit from Brussels, the mannequins and our collection are still in boxes that we haven't seen put together yet. This has been in the making for a while, but all the components haven't ever really found each other yet.

Sofia Hallström: I can imagine. Is it always like that? Does each collection come together in the presentation? Is that what unifies the collection?

Lucy McKenzie: With us living in different countries, we have to be very patient. We sometimes make collections on paper to show each other, just to have that kind of one-to-one, intermediary object between the final thing and the sketch or the idea. Through being in different countries, it's made us become very resourceful and find idiosyncratic ways to work because of the distance.

Beca Lipscombe: There's a huge level of trust that comes with making these collections. We're very different and we have very different ways of looking at things. I've got a designer head and Lucy’s got an artist's head. That level of trust is there so we improvise often. Our working relationship is very good, when I'm working with Lucy, I feel like I can do anything.

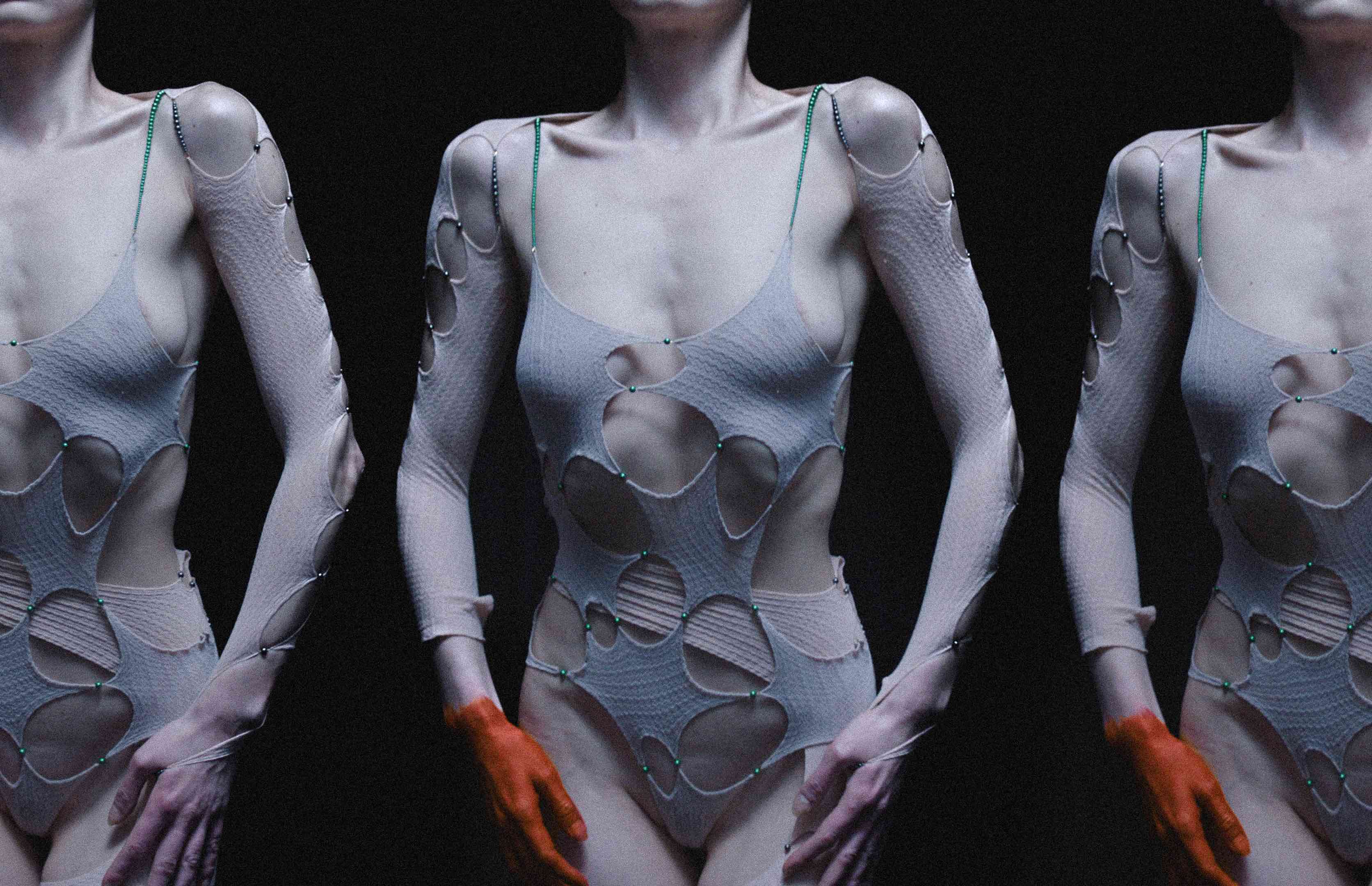

Sofia Hallström: I wanted to ask about the inspiration behind the collection, ‘Big Tobacco’. Could you expand on the theme, how it is translated into the design elements, and what aspects of Women's Tennis specifically influenced the collection?

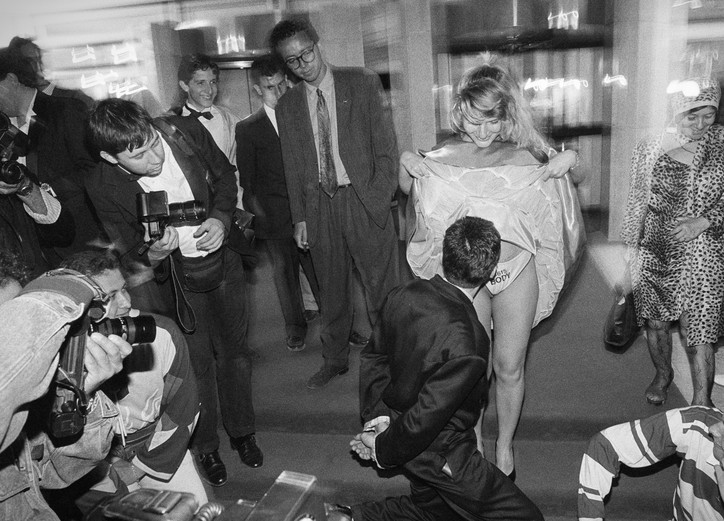

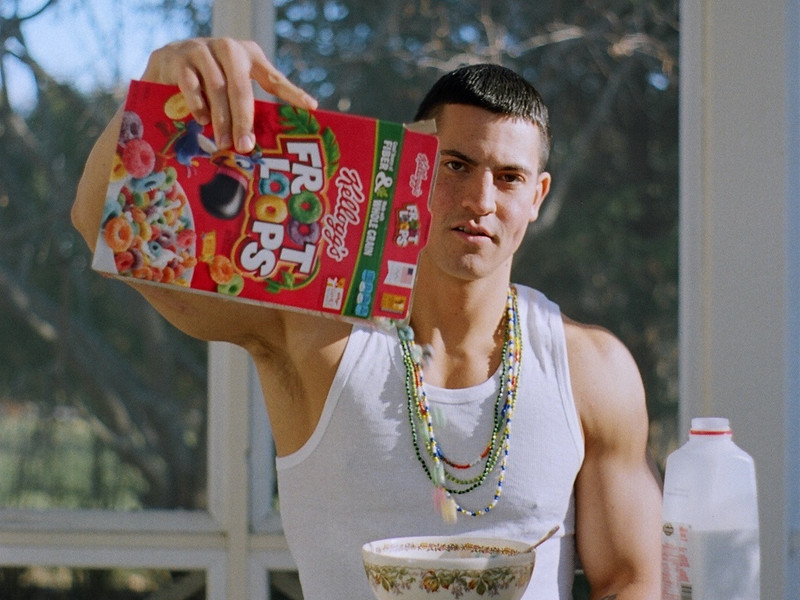

Beca Lipscombe: It's to do with the visual of tennis and what people wear on court, mixed with the taboo of smoking. Until 1992, tobacco companies advertised within sport, which isn't that long ago. Nobody speaks about smoking anymore and, of course, there's a reason why it shouldn't be associated with sport, so we hint on it within this collection.

Lucy McKenzie: In terms of women's tennis, we've always been interested in the way cigarettes were marketed to women, the feminine packaging that almost looks like tampon boxes or something. To continue what Beca is saying, there has always been a struggle for women in the public eye. These powerhouse athletes who are still meant to perform femininity and being sponsored by a company that almost promotes smoking as a diet aid. It's really about mixed, complex messages from these female athletes who just stick their heads down and drive forward.

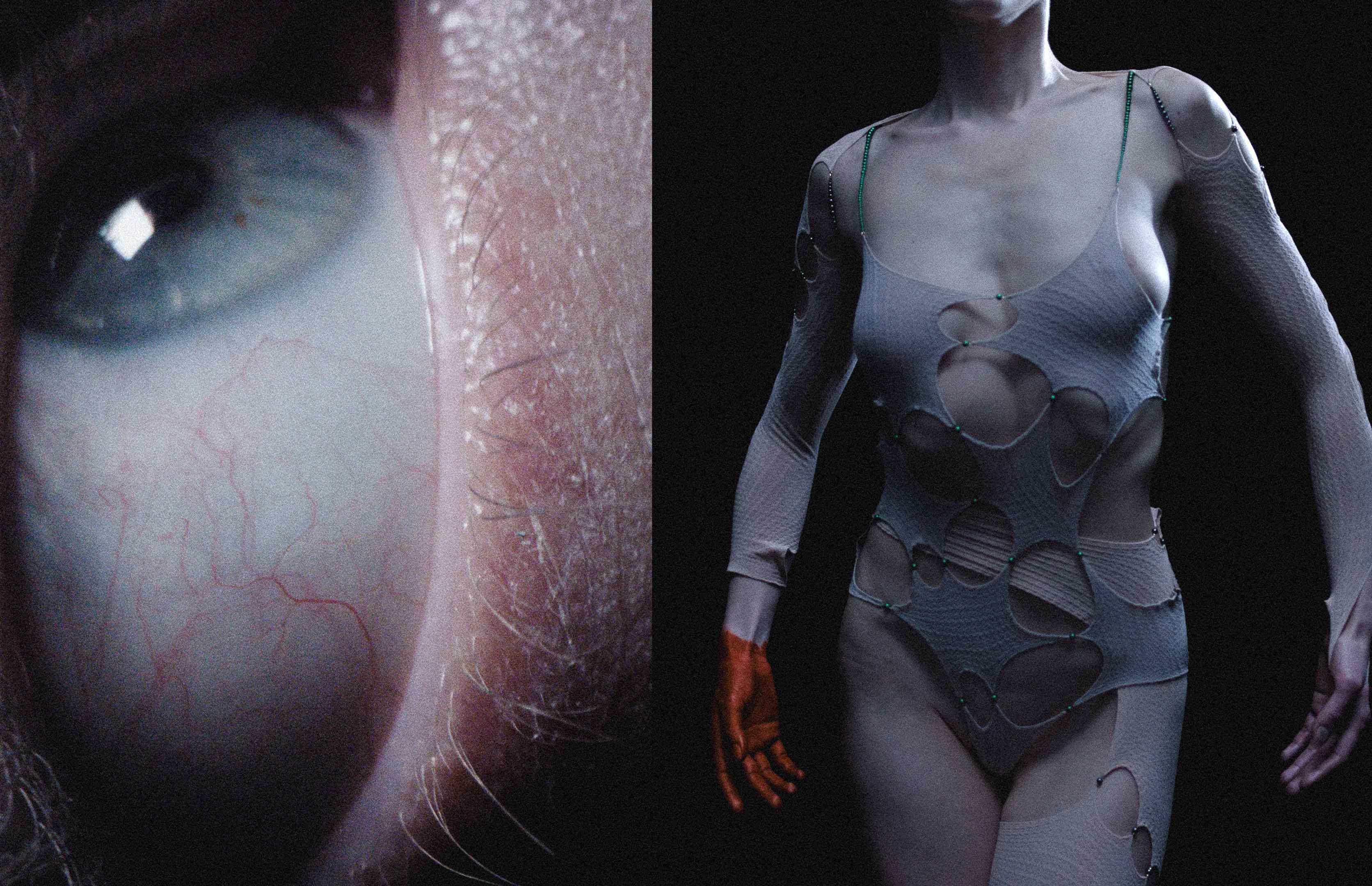

Sofia Hallström: Atelier E.B applies the notion of 'styling' as an artistic strategy. Can you talk about how styling becomes a means of artistic expression, and how it contributes to the overall narrative of the collections?

Lucy McKenzie: There’s so much within art that is profound and kept hidden. All this work goes into making an object, and often that is obscured. Styling brings a certain flatness, it accentuates the image of something. It's about how you read something in a moment as you flip through a magazine. Styling is the accessory, the location. It's meant to be the thing about us that has two sides: wanting it to be meaningful and profound as art can be and satisfying a public that just wants to wear it. Straddling those two needs, making nice clothes for people to wear and expressing our lived experience. We do our own styling, it's an extension of what we're making and how we want the world to see it and it's a pleasurable part of the process. Why would we give that to someone else!

Beca Lipscombe: Building a label from the ground up requires extensive effort, but the rewards are worth it. There's a significant amount of administrative work, contemplating materials, managing distribution, and handling emails. Styling, whether it's Lucy illustrating a collection or collaborating with photographer Morwenna Kearsley on photography, is an essential aspect. It's not merely an add-on; it's an extension of our creations. Through styling, we present our vision to the world as we intend it to be seen.

Lucy McKenzie: When we launched this company, our primary objective was to challenge the conventional notion of a fashion label. Rather than conforming to established norms and templates, we questioned why certain practices were necessary. We began with a clean slate, asking ourselves: "Why do things have to be this way? What if we approached it differently?" Our goal was to redefine what a fashion label could be, starting from the ground up. It's been an intensive process, but the sense of accomplishment is incredibly rewarding.

Sofia Hallström: Atelier E.B is known for small-scale production and ethical practices. Could you speak more about how this is reflected in the creation of this collection, particularly in terms of material choices, manufacturing, and distribution?

Beca Lipscombe: Many people describe us as ethical, but to us, that's simply how things should be done in today's world. It's not extraordinary; it should be the standard. Ethical practices are ingrained in our approach because it aligns with our values and principles. It's not the primary motivation; it's just inherent in our process. When we select textiles, we prioritise manufacturers who specialise in their craft. We assess the company's strengths in design and consider how their textiles can enhance our collection. Rather than imposing our ideas, we adapt to their expertise. We are adaptable, striving to offer products that are accessible to everyone. Manufacturing in Britain comes with its costs, but we prioritise fair treatment and refuse to exploit people. Our goal is to produce in the best way possible, respecting both people and processes.

Sofia Hallström: How do you approach the selection of materials for each piece? What criteria do you consider when choosing manufacturing partners or people to collaborate with?

Lucy McKenzie: Beggars can't be choosers. We're lucky to work with the people we do. We're small, so we don't get to choose much. People don't have to work with us. They work with us because we've built relationships, and they're curious about what we do. We choose textiles based on the manufacturer's specialisation. We observe and understand what they're brilliant at, then utilise it. We don't go in with wild ideas but work with what they excel in. It's a symbiotic understanding. We have each other to sound off about things. Everything is done with consideration.

Sofia Hallström: How did the collaboration with Glasgow artist Steff Norwood for the window vitrine come about, and how does the sculptural design contribute to the overall narrative of the collection?

Beca Lipscombe: We don't have a catwalk show. This is our way of showing our vision. It's how we want our pieces to be viewed.

Lucy McKenzie: Steff is a long-term collaborator within Atelier, he is part of the gang. He's a maker and a scavenger. Working with him, we keep refining the design of folding screens. It's important to have a team that understands what we’re trying to do. We work with a gallery in London called Cabinet, and one of the directors Martin McGeown was a window dresser for a long time. As retail declines, beautiful window displays become art. It's about preserving and transmitting cultural knowledge.

Sofia Hallström: Given that you don't sell in retail shops, how does the showroom or exhibition model contribute to the customer experience and the interactions you aim to foster with your audience?

Lucy McKenzie: Selfishly, we learn so much, get good ideas, and feedback. We did a stock sale in Edinburgh not too long ago, and we had never done one before. We got a deluge of people who want to come in, chat, and hang out. It's a dose of socialisation, meeting great people, and getting great ideas. We want the clothes to be simple, we don't want them to be shouting and we know that we are really good at expressing those ideas and enthusiasm. It's for us as well.

Beca Lipscombe: Who better to sell the clothes than us? We designed the store, so we should be there to present them. People like to come back and tell us how they feel about the clothes and how they store their clothes. Lots of people store our clothes in the freezer as they love them so much that they don't want the moths to go near them! We have many customers from all over the world and we're always looking for new customers! We strive to offer a wide range of products to ensure accessibility for everyone, not just the elite, though clothing is expensive to make in Britain. This inclusivity is essential to us, it's important, and we try to do it the best way possible.

Sofia Hallström: The brand mentions embedding critique into clothing. How do you approach incorporating social or cultural critique into your garments, and what role does fashion play as a medium for commentary in your collaborative projects?

Lucy McKenzie: Maybe I can speak for both of us. We're only really interested in that kind of engagement when it's genuine. There's so much performative sloganeering and politics in fashion that we're just so inured to the slogan t-shirts and catwork shows with placards. We know the compromises that are essential to make fashion. Those critiques should be very subtle, and that's what someone like Margiela did well, exploring the body and representation in a quiet way.

Beca Lipscombe: It's a beating heart for us, but a quiet thing for the wearer. They don't have to know the symbolism; they can wear the garment if they like it! For instance, we made a Scotland football jumper, pixelating the image so that it is appropriate to a knit pattern. Anyone from Scotland would know what that image is immediately. Though, when we sold it in New York, people related it to Chanel due to the colours and floral pixelation. People interpret it differently. It's not a drive that everyone should understand the clothes' meaning; it's just how we design with a deep-rooted purpose.

Lucy McKenzie: The genesis for that collection and that jumper in particular is connected to the fact that women were banned to play football in the UK by the FA until the 70s. We found that so shocking and it really helped to understand why football has the status that it does in Britain. To get from this fact, which is political, and via that, you were more likely to see a woman in Britain at that time as a glamour model or a murder victim, rather than a professional athlete. It evolved from a political statement about women's rights to a lovely cashmere jumper.

Beca Lipscombe: There’s a lot of depth to the work, but at its base they are beautiful garments. Take the football jumper, Scotland is not good at football, but we have the classiest football kit. It's a classic, it's navy and white! It is something that you want to wear so why not utilise this?

Sofia Hallström: I support Fiorentina, they've got a beautiful purple kit…

Lucy McKenzie: In society, we don't take the time to stop and really take fashion apart. That's why we love fashion history and academia so much. and the work of fashion historians like Amy de la Haye, Judith Clark and Caroline Evans are crucial to us. We love taking apart fashion, understanding its depth, and preserving cultural knowledge.

Beca Lipscombe: The jumper that we spoke about recently got acquired to the V&A archive in London, and the V&A Dundee have the outfit on permanent loan in the Scottish design gallery.

Sofia Hallström: Looking ahead, are there any upcoming collaborations or projects that Atelier E.B is particularly excited about, or themes that you'll explore in future collections?

Lucy McKenzie: Our sculptures that will be part of the Cromwell Place presentation will be part of an exhibition of my work as an artist at Z33 Museum in Hasselt. I’m excited because the building was designed by a woman architect, Francesca Torzo. She worked for a long time with Peter Zumthor, who I am a big fan of. It's a really special building.

Beca Lipscombe: On this occasion, we're working with an organic cotton jersey manufacturer, a company called Assembly, and we are hoping to collaborate more with them in the future on sustainable athleisure. We're open to working with big sports companies and exploring new projects for design museums.

Lucy McKenzie: We work on long timelines, appreciating developmental time for our projects. We always have plans in motion, whether it's for next week or next year. Our major exhibition that took place a couple of years ago, ‘Passer-By', underwent three iterations and included a catalogue. Eventually, we'll be inspired to work on a similar project again.