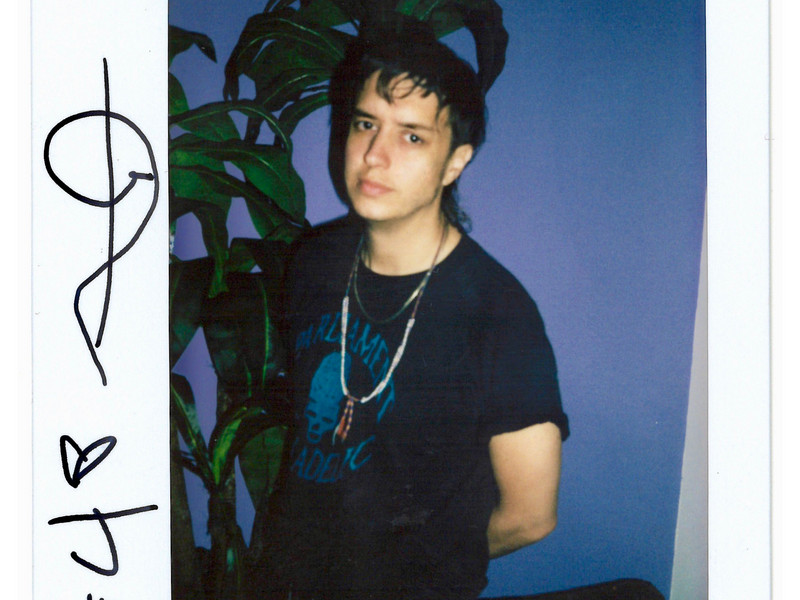

Blue Hour Lasts A Long Time In Hamond's World

"I just believe that there's energy watching over us, and that comes through in that song. And once you start looking for patterns and numbers in the world, then you start to see them more. Which is obviously something that's very talked about nowadays, but it's true. It goes to a deeper thing where it's like when you're open to seeing things in the world, then they come to you to you." says the singer.

On a sunny day in California, office had the opportunity to meet up with Hamond in Silver Lake Park, his favorite park to talk all things music.

So you grew up in Houston, did your parents inspire any of the music you grew up listening to?

Yeah, definitely. They had very opposite tastes of music. My mom was very much into disco, Earth, Wind, and Fire, Michael Jackson, Sade, and my dad was very much classic rock, Beatles, Led Zeppelin. And I went through so many phases of music, because of that, which I'm actually really glad because at a certain point, it was just trying to culminate all the different, opposite genres, that I've been listening to all my life.

Are your parents from two different places, is that why they have different music tastes?

Not really, they're both from the Midwest. My mom's from Chicago, and my dad's from Detroit, so, not too far.

Taking from each of those sides, how did you get into music?

Well, it was on my mom's side, art was her big thing, but music and her family, my grandfather played in the Chicago Symphony, and my uncle was a conductor. It was all classical music leaning, for sure. But just being around that as a kid, and then I just started picking up instruments, and trying to do bands, but I was too controlling as a kid, to be in a band, "No, play it this way."

What's your sign?

I'm a Pisces.

Oh really? I feel like Pisces, aren't that controlling, maybe they're just particular?

Yeah. I don't know signs that well, but I was talking to the guy that does my hair. I was like, "Yeah, I'm a Pisces, I think my girlfriend told me I'm a rising Leo." He was like, "Oh, that's where the controlling part comes in."

So you were in a band, how old were you?

This was in middle school, and it lasted maybe a month. But it's funny because I was at this bar two weeks ago, you know Zebulon? But I was walking outside of the bar, and some guy came up to me and was like, "Brian Hammond. You were in a band with Jackson Beasley in seventh grade, and we were good friends."

I was like, "Oh, that's crazy. I don't remember being in a band." But that made me think back on it again, and how bad I was at being in a band because I just couldn't let people do their own thing. That's when I realized I had to do my own thing. Well then I started— I got a MacBook, when I had my bar mitzvah, in seventh grade. So when I had my bar mitzvah, is when I got Garage Band on a computer, and then I started producing. And then I started producing for rappers in high school, and then I was secretly singing in my room, but not letting anyone know.

Doing covers on YouTube?

Yeah, there you go. And then I started singing on some of the hooks, and then it got to a point where I was like, "I don't want to do this. I want to make my own music." And then it just transformed into that.

Do you remember the first song you made, and what it was called?

Yeah, it was called "Feel It," makes me cringe now thinking about it. My parents loved it. They were like, "That's a hit!"

Wait, what did it sound like, and what were some of the themes?

There were no themes, I was 14. I was just like, "Oh, these sound like some cool words that go over this stuff. Can you feel it?" Oh my God.

Well, on the opposing side, do you remember the first song you made where you were like, "Okay, I could do this music thing professionally?"

Yeah, I think so. It was probably when I was 18, it was this song called "Keys," that I posted on SoundCloud. But yeah, that was one that was the first song I made, that was my own, not me producing for someone else, or me featuring on a hook, or something, it was like this is fully my art, my project.

And then you made the next song that you thought was good, and what did you learn from the first song that you brought into the next set of songs?

I don't know, it was a long time ago, it's hard to remember. I know now with each song, maybe not with each song, but with each era, it's stepping back, and being like, "Okay, this got better, but maybe I need to hone in on..." With this next era that I'm going into, it's almost looking at it as a full collection, art, or fashion collection. One of my friends, Lisa, who I worked with, as a director, on this video that is going to come out, she went to fashion school. We were just talking about how the first step to any project is the research phase, and how I'm in this phase right now of pulling all the sounds I like, and inspiration I like. So that then once you go into the phase of making the actual music, you have these boundaries that you're trying to exist within.

What were some of the specific resources you were looking at when you were doing research?

My whole goal is to try to combine genres that were really inspired by electronic music, UK Garage, and old drum pockets of that kind of sound, but make it more musical, and alternative. So I was listening to a lot of Stereolab, Broadcast. I've always loved Pharrell and the Neptunes, chords, and jazz. But then trying to match it with these electronic textures, the whole idea with this project, Pirate Radio, was classic future vintage, if that makes sense?

What is the pinnacle of utopia in a sound for you? If there's a song or a specific chord you like, what is that? How are you trying to chase that perfection?

Man. This is going to sound crazy, but the chord progression of "Senorita" by Justin Timberlake. That's so fucking crazy. Every time I go back, and listen to it— and I learned it on the piano, I think like, "How did Pharrell come up with these chords?" And then just the pocket of it, and the way the melody comes in on it, is just so perfect, that is one. Stereolab has this song called, The Flower Called Nowhere, the chord progression on that, and it's in a super weird time signature. It's just things that are like, "How the fuck did they think about that?" There's a few of them, I'm sure, I can't think about it off the top of my head, but those are a couple for sure.

Did you see the documentary with Pharrel, and Justin, where they were making Senorita?

Oh yeah. Justified? The amount of times I watched that as a high schooler, my play count on that is probably a 100 each, separate, I think there's three 30-minute videos on YouTube, that I watched over, and over, and over again. Yeah. They don't have him making that Senorita, though.

Yeah, what song was it?

They did, "I Love You." I think "Rock Your Body." And "Let's Take a Ride" aged the best out of that.

So with your new project, can you paint the sonic landscape of what you're putting out?

Yeah. Well, I started to touch on it, matching electronic textures with vintage textures, so we used a lot of analog equipment, and I wanted this project to be very musical in the sense. A lot of times electronic-leaning music isn't very musical. Yeah. So trying to take influences from that, but still have it rooted in alternative music, musicality, using live instruments, pianos, guitars, and then we used tape machines on a lot of stuff. They give it a super analog, retro texture. There's this interlude on the project, called "The Credit," And that whole thing was printed to a tape machine. And then there's a pitch wheel on the tape machine, and I played around, moved it, and then you can hear it, manipulating it. And it just sounds more human, than it would if you were in the software program, drawing it in. Well, the whole theme of the project is, it's called "Pirate Radio." Do you know what pirate radio is?

It's like UK garage?

Yeah. Well, it's it started in the UK, but it started with the classic rock era, where the radio wasn't playing what people— or what the youth wanted to hear, pretty much. So they would steal the broadcast, hijack the radio station, and play their own radio, the music they wanted to hear, onto it. And then it just turned into UK electronic music, and that whole world, but it's pretty much people in their bedrooms running their own radio station with all this equipment.

And so, me and TJ, TJ is like my executive producer I do everything with, we were referencing that whole feeling and the spirit of that. And how when we make music, it's like we're in my bedroom, or in our studio where we're tinkering with things, and where it's just the two of us, we're running a radio station. And then leaning into that with the way the music is made, using knobs, and equipment, all that shit.

Have you ever hijacked any parties trying to DJ?

No, but that is what we're trying to do with that. So I really want my first shows for this project to be — We're talking about finding abandoned office spaces, and warehouses, and pretty much building out what pirate radio looks like with all this equipment, making it an art piece, and then doing a show there, that would turn into a rave after it. With Charles, my other roommate, he is a crazy DJ, and has been launching this thing called, "Thank You For Sweating Out Here." Which is going to be underground Raves, pretty much, and he would help put that on.

What got you into UK garage? Was it from your dad?

Not really, I mean, neither of my parents were really into electronic music, that was after their time. Yeah, I don't know, I've always loved electronic music, but good electronic music. I fucking hate EDM music, but it's called fucking fist punk, bro. It started with Daft Punk, and then it just escalated into getting into Aphex Twin. And this whole world, that all of the electronic music I was really liking, was coming out of the UK. They're just so much better at it doing it in a tasteful way. It's a certain way that British people are able to incorporate electronic music, and not make it fucking corny.

But you know why that is right?

Why?

There's a big theory about people in the UK being really good at art because their environment is highly depressive. So the theory is that people here making art in America is not as great, as deep, and more surface level is because we have a lot to look at, a lot that's stimulating.

There's definitely something to that. I think my favorite time we make music is when it's cloudy, and raining out. Yeah. I'm trying to live in London for a while, at least do a year there, or something. But January is my favorite month in LA because people think it's sunny all the time, but in January, LA is cloudy and rainy. Probably half the days of the month, and that's when I make the best music.

You have this evangelical and spiritual hue to your music. You released "Angels" on the date 02/22/22, and your newest song is called "Angels." Can you talk about the spiritual elements you experience, and put into your music?

Yeah. Well for the first single "Angels," obviously it's directly tied to, that's what the whole song is about. But I don't know, I don't want to get too deep into my religious relationship with God. I'm trying to figure out how to do it without it, but I'm not afraid to talk about it. It's really just a matter of, I don't know exactly what I'm comfortable with saying. But I do believe in a higher power, and my dad, when I was a kid, would always tell me, and my sister, that we had specific guardian angels designated to us, and mine was named Chester. I still talk to my guy Chester up there, but I don't know, I don't believe in it in such a literal sense, but I believe in the higher power. I just believe that there's energy watching over us, and that comes through in that song. And once you start looking for patterns and numbers in the world, then you start to see them more. Which is obviously something that's very talked about nowadays, but it's true. It goes to a deeper thing where it's like when you're open to seeing things in the world, then they come to you.

Do you take that same approach to making music? Are you open to whatever sounds or ideas come, to you, even if that's not the plan you had for that day?

Well, that is one thing about music, that's why the research phase comes in handy. You try not to be too methodical about it. That's one thing, with me and TJ, is when we work, it's all just how we feel. But it's, "Let's get this idea out. Let's do this." And then once we're not feeling it, let's go to the next one, and come back to it. And going with the energy of the room, and how it makes you feel.

The methodical part is you do it beforehand, where you try to figure out what you're trying to do, in general. And then you go in with that, in your subconscious, and then you make it with that in mind. But you have to let the energy flow when you're doing it in person, otherwise, you just disrupt the whole— you end up being like, "Oh no, no, no. We need to get this perfect." There's energy in the imperfections, it makes it more human.

What you would tell your younger self about making music now?

That's a really good question, I'm really thankful that I don't really regret —I made a lot of pivots throughout being a kid of like, "Oh, I like this. No, I like this." and jumping around. But I never would've gotten to a point where I would want to create something totally new that combines genres, if I hadn't gone through those phases of trying to do so many different types of music. So I would probably just tell myself, "Keep going kid."

Were you one of the kids like up all night on Reddit, or looking for music?

Yeah. Well I was up all night making beats, that's for sure.

Were you selling beats?

No, I tried to, at one point, it's just such a soul-sucking thing to like, "Oh yeah, I'm going to make these beats that random rappers across the world would like?"

Pierre-type beats?

"Type beats" are the worst. I just remember I was such a huge Kanye fan in high school. And when this documentary dropped, it reminded me of what it was like because I was staying up waiting for it to come out. And I remember staying up late, waiting for "Good Fridays" to drop. And being on forums about gear certain producers would use. And it's like a rabbit hole that you go down with like, "Oh, I wish I had these things that these producers I look up to, or artists I look up to have, or use." And then it's such a cliche to be like, "Oh, you don't need those things." But you really don't need shit, you just need your ideas and your own self.

But then that goes hand in hand with making music for yourself and selling music. Have you been hesitant about getting an executive producer, signing with a label, and getting a marketing team, if that might take away from the true artistry of your music?

Yeah. I think in the first couple of years, I had spent coming out to LA, and then eventually moving here. I mean it's obvious, but the industry in LA is so gross. I mean, but there's a great side to it too. So you just find your bubble, but once I found my bubble of people that I want to be surrounded by and just stick by, then it's like you block all the other shit out. And once you have that, it made me realize that like, "Oh, there's certain ways people see music, that I don't want to have to be associated with, at all." Not associated with, or just work with because I don't want those opinions on my music, the way I look at it now is like, "Am I going to be happy with having this out in 10 years?" Or when I'm older.

Wow. I've never heard anyone talk about that, the longevity of their music in that sense.

That's the motivating force for what route I want to go, what I want to put out now, with this project. And going forward from now on is like, "Am I going to be happy with this being out when I'm old?"

If you could have one person living or dead review your music and give you a critique, who would it be?"

Pharrell is one. I was going to say Paul McCartney. And Guy Manuel or someone from Daft Punk.

Why would you want Pharrell to critique your music? What advice would you think he would give you?

The way he hears chords, and I'm just curious what he would say like, "Keep doing that." I just admire him, the thing about Pharrell, is that he has such a distinct sound. When you hear a Neptunes beat or a Pharrell beat, you can, most of the time tell if you know the sound?And my goal with this next era, and a little bit with this project, but even more so, probably with every project, is to almost put a little more boundaries on places you can go musically. So that I can make as cohesive, and identifiable of a sound as I can, and I'm curious how he did that.

That's true, because I can always, no matter what song it is, I'm like, "Pharrell produced this." But with other people, I know sometimes Timbaland, like people can hear that.

Timbaland is super identifiable, not as the Neptunes, but a lot of it comes from liking chords. It changes everything, seriously. Both Tyler and Pharrell use jazz chords, major, minor seven, which is something I've always gravitated towards. There was this song, it's an old classical song that uses major, and minor, seventh chords. And I was learning classical music at the time, and then I heard that, and I immediately pivoted to jazz music because I was like, "This is so much better." It just feels like, it's a different feeling.

I love jazz, it's so boundless. I feel like people are very pretentious with the way that they love jazz, but it literally is just like the scope of all music that you hear, all of it has jazz elements in it.

Yeah. It's literally there's no wrong to it. Jazz is the most human part because as we were saying, humanism is embracing the mistakes of it. Jazz is so technically wrong, but it's so it just feels right.

And Paul McCartney?

Oh yeah. Just him as a songwriter, I'm curious about his process in how often they wrote songs with the Beatles. And how I remember hearing they would go in, and just write a song a day, or multiple songs a day, and then go to the studio, and hammer them out. It was like sometimes you can get too caught up in trying to make the perfect song, but it's clear the way they were doing it with how much they churned out, it was like they weren't thinking too deeply about it. I'm just curious on how he approaches songwriting.

If this was Brian's world, what would it look like? What are the rules? What's going on? What is the background music, at all times? What IS your ultimate utopia?

I want to see a city where— it probably wouldn't work logistically, but I want to see a city where the whole priority is everything looks beautiful, and architecture is the priority, and arts is the priority. Imagine walking through a city where all the buildings were built to be interesting, or pleasing, and all work together.

But isn't that the society we live in now? We're so caught up in the beauty of everything, and that comes in with capitalism, as well, because you're trying to sell beauty? We're all so obsessed with the beauty of everything.

I don't think so because then think about how much stuff is built just to make money, or just because it's practical. Obviously, not everyone is an artist, but I will imagine a world, or a city, where everything was built with art in mind, and that's the priority. And then I don't know, you walk into a fucking Target, or a grocery store, instead of them playing fucking old Michelle Branch, they're playing cool new, someone's curating it. And it's like, "Oh this is a cool song. What is this?" And everywhere you go, is just good curation in mind.

Okay. Is the sky a certain color, or not?

I like blue. The simulation's kind of beautiful. Maybe blue hour would be extended by three hours, I love blue hour, but it only lasts five minutes, I wish it lasted like an hour. Blue hour is right after the sunset goes down, or right before the sun comes up, where the sky isn't orange yet, but everything is like dusk blue.