I. The South Beach Pier Rats

South Beach Shark Club as a documentary is broken down structurally in chapters, like all old fables. It’s a fitting device, because Miami is ultimately a place built on myth.

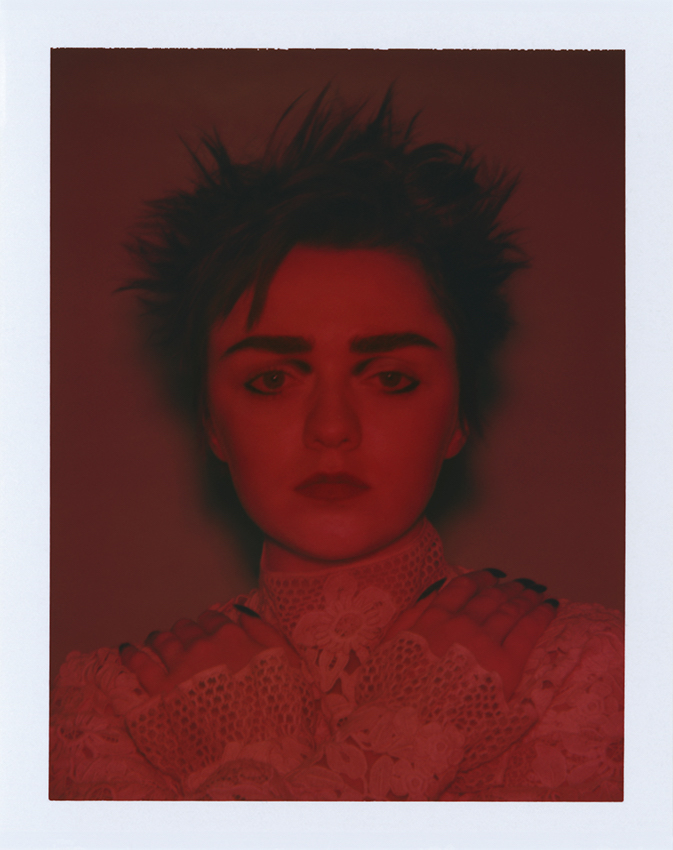

If you stay on South Beach long enough, you’ll find yourself stepping into a time warp where nothing is new and nothing is old. Miami’s history is in a temporal space trapped in a haunted Art Deco hotel. No one is from there — even myself, who’s from here. A multi-generational family like the Bustamantes is rare. That transient nature adds to the myth, though; it could be 2024 or 1974, and yet it’s still a place where the Latin American and Caribbean political diaspora, the Jewish, Russian, and European emigres, beach hippy weirdos and junkies, artists, and misfits alike swelter together. By mid-June, those who've been crazy enough to make Miami home are desperate enough to escape their suffocating reality of swamp humidity, discovering refuge by haunting the nightclubs of Collins Avenue by the Art Deco Motels, milling about like wispy tipsy ghosts.

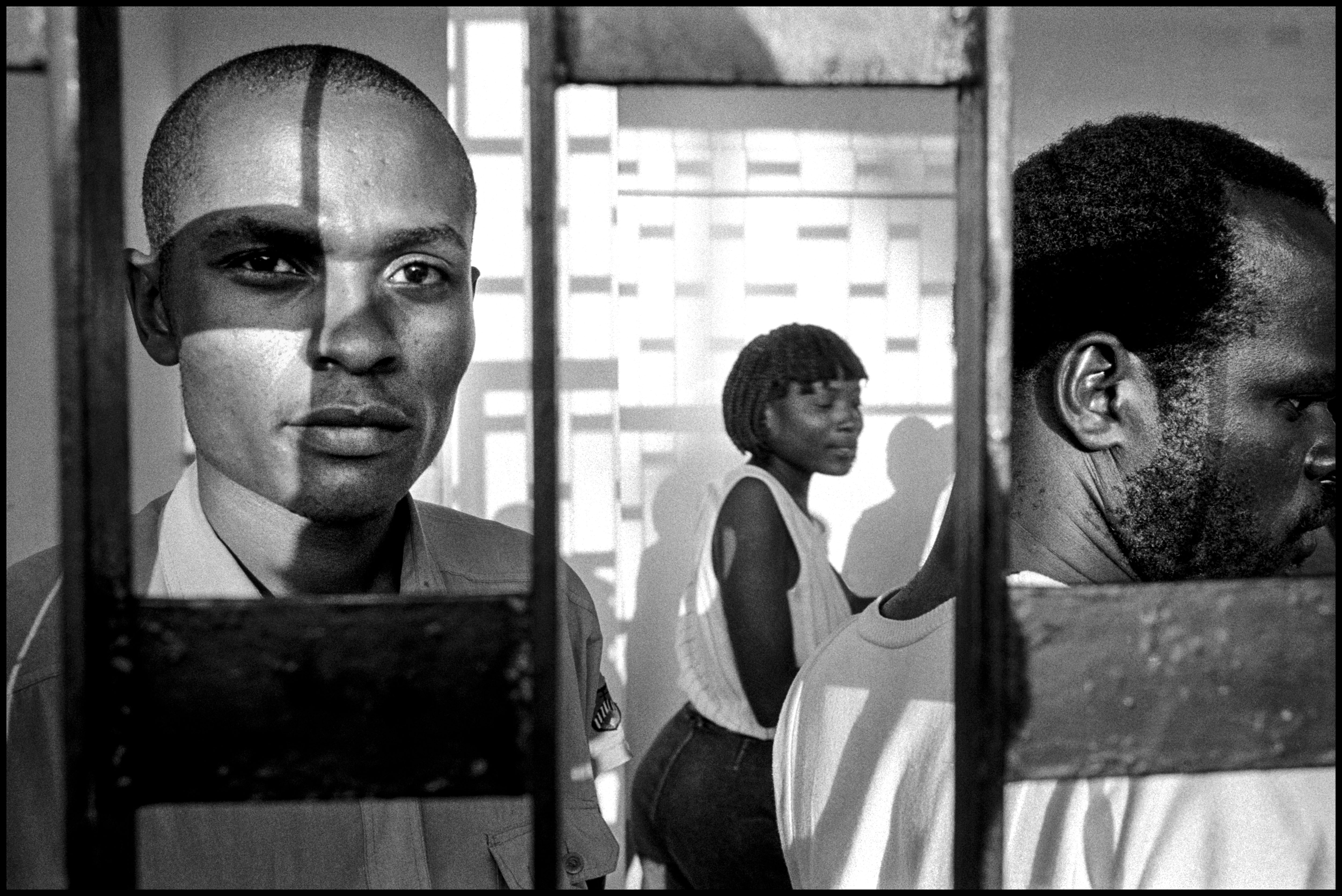

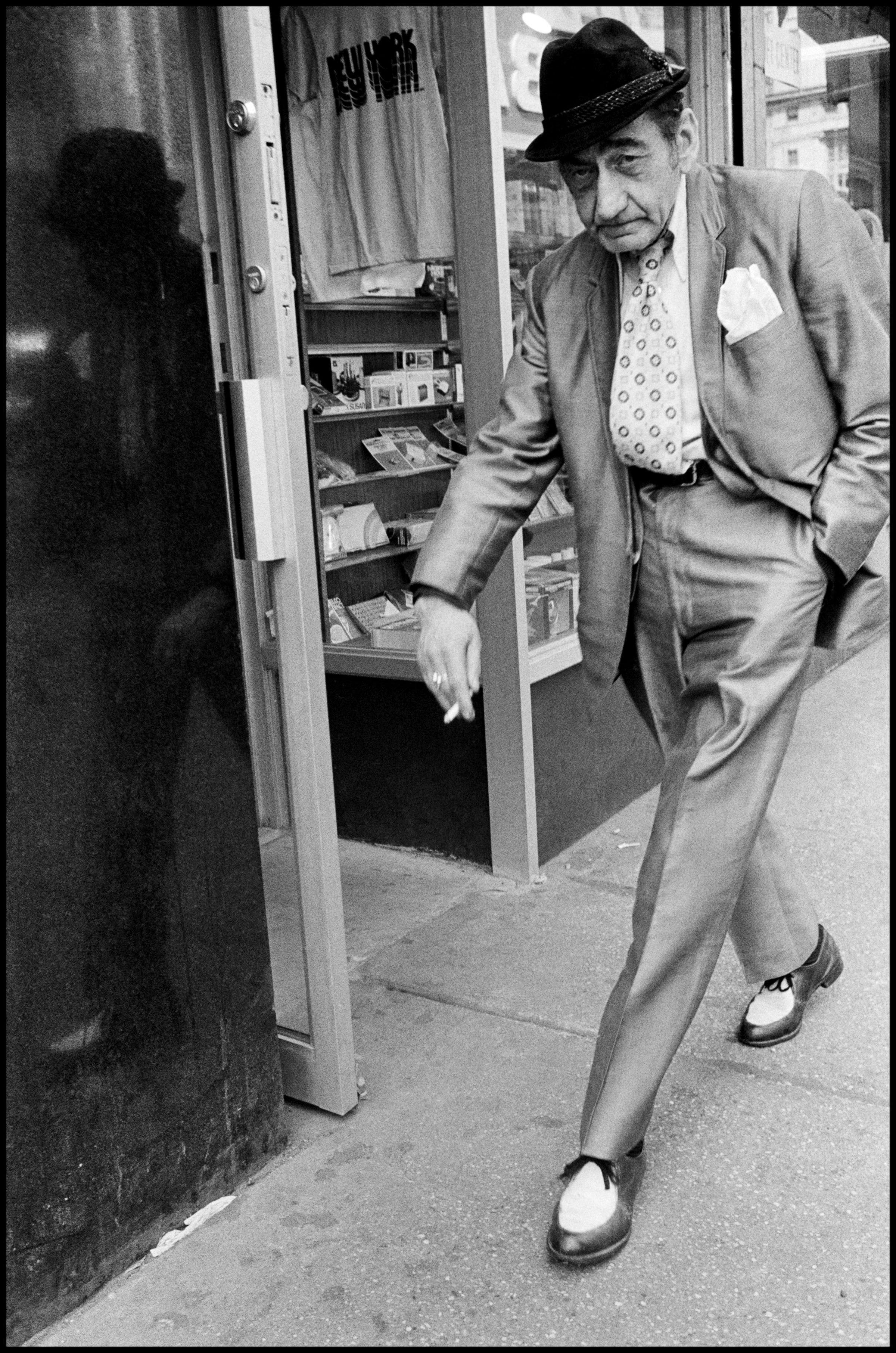

After sunset, when everyone else leaves the beach, drunk and pink, a different group of strange characters come out to play. Despite her changing nature, there are points of focus in South Beach that remain unmoving through all the burn and blur. Mac’s Deuce, open since 1926, and owned and operated by Mac Klein from 1964 until his death in 2016, is one. Joe’s Stone Crab, open seasonally since 1913, is another. Those points of focus are all interwoven into the tapestry of the beach’s history, its legacy. Along the sand at night, there lives those who subsist on those excesses and revel in the thrills the beach has to offer: the shark fishers.

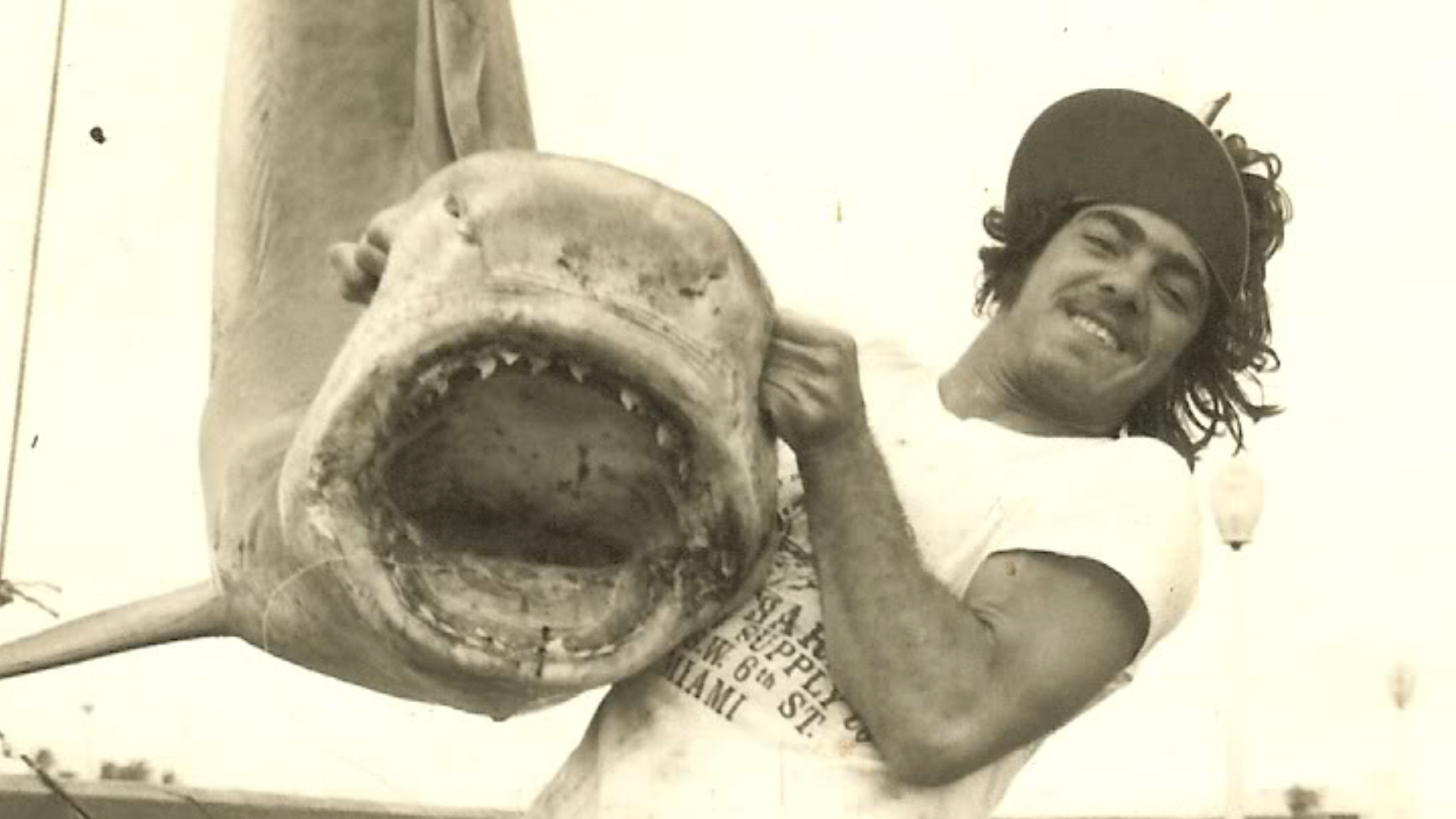

Rene De Dios caught his first shark when he was fifteen, in 1971. Not long after, in 1973, the film rights for an unreleased novel by a man named Peter Benchley were sold to Universal Pictures. That novel, Jaws, came out in 1974. Steven Spielberg’s beloved adaptation came out the next summer, in 1975.

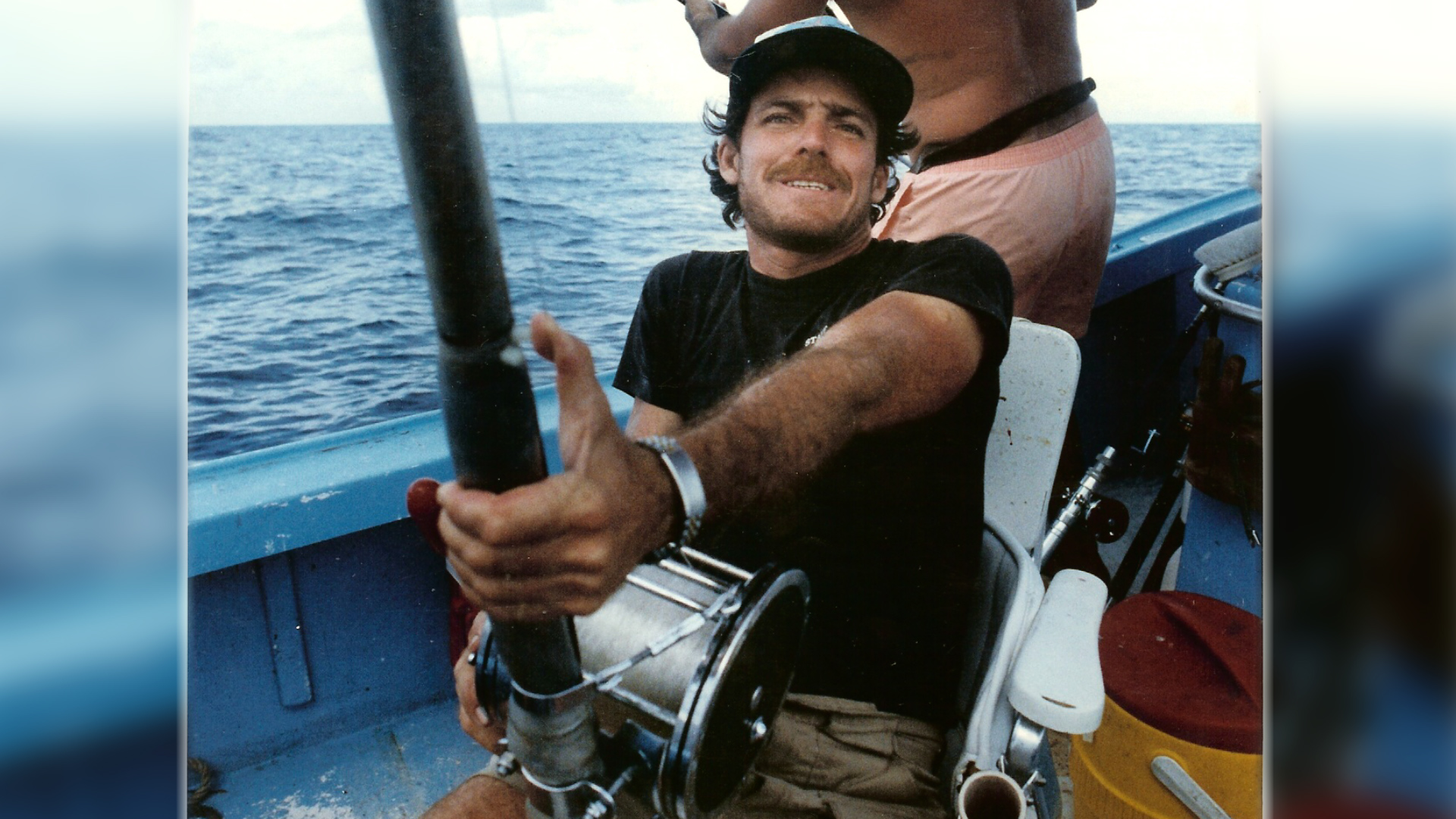

After that, fear and fascination with sharks became monocultural. Shark fishing competitions began to take place along the coast, by either land or boat. De Dios, depicted in his early twenties, had assembled a crew nicknamed “The South Beach Pier Rats.” Together, as displayed through the documentary's archival footage, they dominated those tournaments throughout the late seventies up until the mid eighties.

This period ended semi-abruptly in part due to the influx of Cuban immigrants with the Mariel Boatlift in 1980, which, among other factors, induced rising crime rates in South Beach. As the documentary explains, the pier where Rene and South Beach Pier Rats competed went into disarray, and was demolished in 1984.

Tuesday, May 7th, 6:05PM:

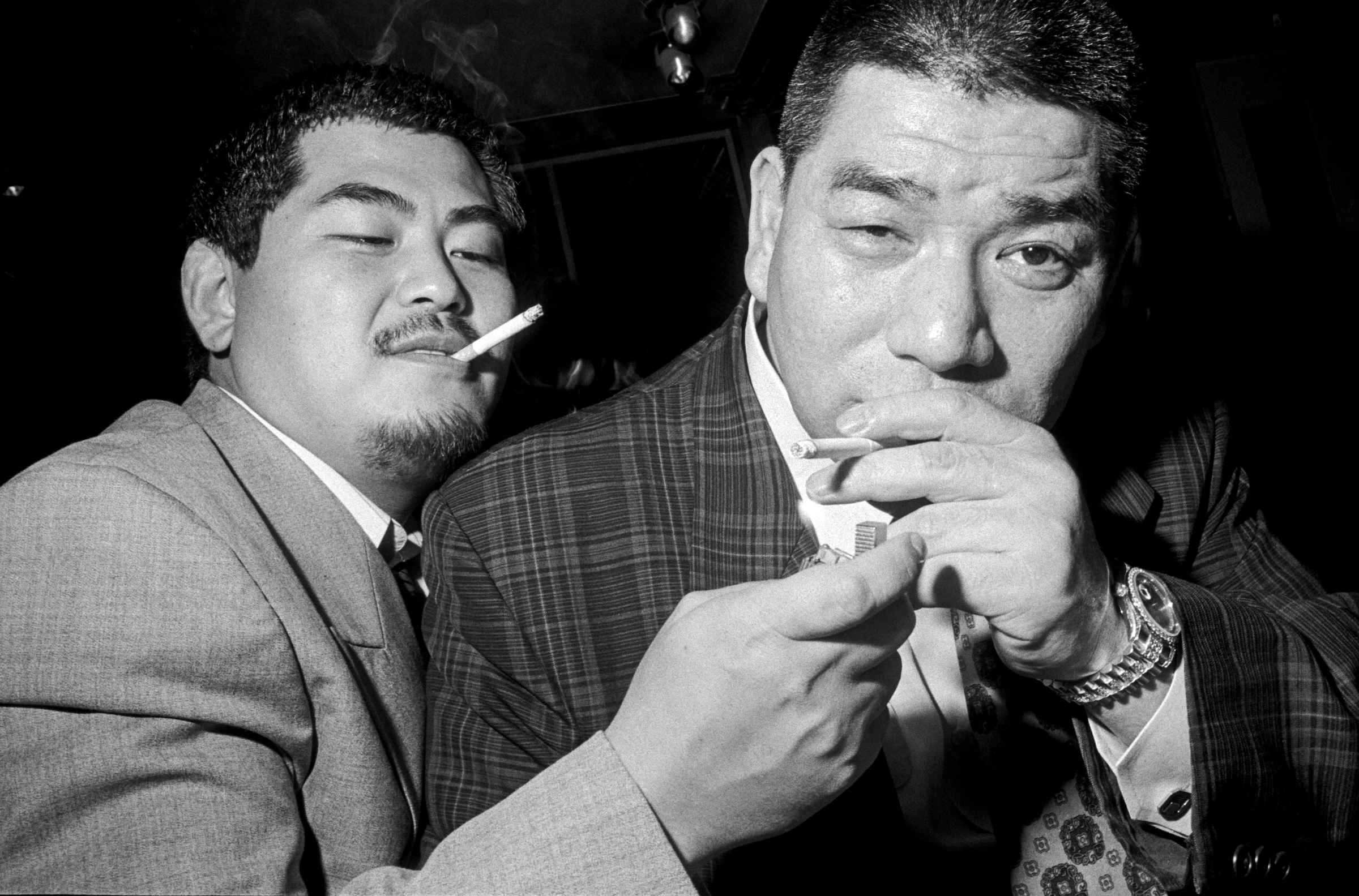

It usually takes about four hours to drive south from Central Florida to Miami on I-75. Robbie picks me up in a minivan on 14th and Collins, with Pedro riding shotgun. Robbie is already barefoot, and the two of them are railing cigs and gleefully blasting Jim Croce as we make our way. It’s golden hour and I’m laying on the floor in the backseat, letting the breeze hit me.

Once we park on 30th and Collins, we stop to get some supplies, before heading down to meet up with Seaweed Jr. We go to the mini mart for 3 six-packs of Stella Artois and a couple of packs of yellow American Spirit cigarettes, all the supplies we needed for a day spent attempting to do something objectively silly: catch some sharks.