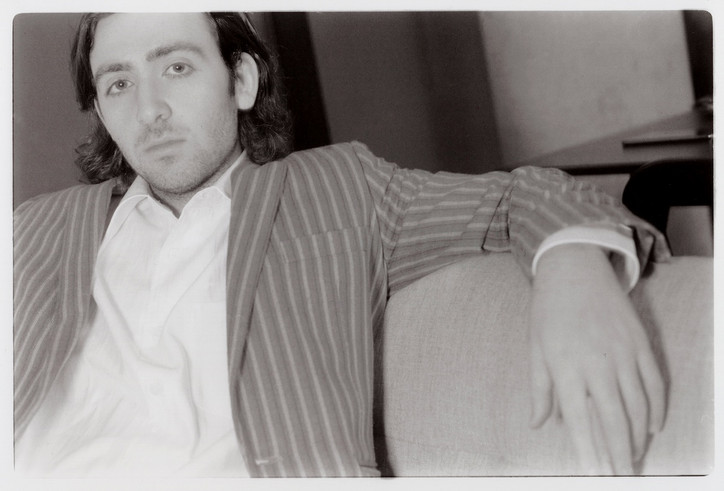

The polarizing values of seclusion and companionship in Allen’s life are accentuated by the nature of his environment: placid woodlands, serpentine pathways, a big, blue body of water. When I connect with Chamandy through Zoom, he’s eager to contextualize the journey behind the biggest piece of his young career, delving into the myriad of unrelated influences threaded into his process. At the core of his desire for artistic fulfillment is an unfettered admiration for Chief Keef, who, like Herzog, turned precocious spontaneity into world class artistry, infinitely imitated. Last year, Allen Sunshine was the recipient of the TRT First Cut+ Award at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival in the Czech Republic. This July, Chamandy will be in Germany for its world premiere at the Munich International Film Fest.

The way Chamandy describes Allen Sunshine is like a soccer dad raving about his daughter who plays striker for the school team; the sheer level of pride shines through immensely. Across half an hour, Harley Chamandy goes into detail about the subtleties that make up Allen Sunshine, what he’s learned about the film industry so far, and the use of music as a storyteller.

Olivier Lafontant— Allen Sunshine largely centers around the life of an ambient music producer and former record executive. Where did the inspiration for this come from?

Harley Chamandy— It all began with an artist named Ethan Rose who did all the music for my film. He’s an electronic artist who did music for Gus Van Sant’s Paranoid Park (2007) and Showing Up (2022) by Kelly Reichardt. One day when I was in high school I had his album called Ceiling Songs and it made such a strong impression on me that I kept listening to it every day, and it sort of got me into that world of that music. When I was writing this script, I always knew that it had to be that type of music, I just didn’t know that I’d be able to work with my favorite artist, Ethan Rose. I was playing his music the whole time while writing the script and once I finished it, I reached out to him [by] cold email ‘cause that’s my thing and you never know what will happen. He really liked the relationship with Allen to the music and that’s something he really wanted to take on, and he thought that was an interesting challenge for him as an artist. I really think [ambient music] is the most introspective form of art and of music, and I really thought that I had never seen that in film, you know, someone really making art for themselves. In a larger context, I think that electronic music is an artform that’s really for the self and what can happen with the instruments. It’s never really about thinking about the consumer, which I was very interested in.

Yeah, especially with Allen in the movie. There’s the scene where his brother sees his studio and asks him what it’s for, and Allen tells him that it’s only for himself. How do you feel like the music itself informs the narrative of the film? How does it represent Allen as a character?

Well I definitely think that it’s a tool that’s used to display the introspection of the character––how he’s feeling, what he’s thinking about––without having to say anything. Just through the music we can understand his state of mind, and how he’s feeling about things. After the brother comes, the music is way more somber, and then when he hangs out with Bill, the man who comes with the fruits and veggies, there’s something more uplifting and optimistic. I thought it was so interesting to play with the headspace of the character in regards to the music.

Considering this is your debut feature film, what are some of the challenges that came with fleshing out a script across 80 minutes or so?

Literally everything you could imagine. They say don’t work with dogs, don’t work with kids, don’t work with fire, don’t work on the water; I literally chose to do all of it. Plus we shot it on film which was another crazy challenge because we shot in Canada, two hours from the city where we were developing, so we had someone drive the film back every day. I think the biggest challenge really was getting people to believe in a young filmmaker. I made the film at 22 and [had to gain] people’s trust, not just on the financial side of things but also on the creative level. Making a film is very challenging but also very rewarding.

You mention shooting it on film and I noticed that within the narrative itself, a lot of the items and tools used in Allen Sunshine are analog: Allen’s music equipment, his film camera, even the housephones. Why did you feel like it needed to be in a time period that represented that?

That was a huge part of the film. I always had this feeling that I wanted all my films to feel timeless, like there was no way to feel what the time period would be. When I was developing the visual language and shooting on film, we had a production designer, but I was so specific on finding my props on eBay and I feel like every little detail mattered so, so much: the color of the housephone, what kind of camera he was using (a Contax G2 ‘cause I think that’s the nicest looking camera), all the synthesizers––that was one of the biggest challenges of the film because it’s so hard to find this gear. I spoke to a lot of costume designers before doing the film and no one could understand what I was trying to say, so I worked with my girlfriend who has never done costume designing before, but she almost spoke the same language as me in terms of what I was trying to get out.

There’s a real pervasive sense of subtlety that moves the plot along and the majority of the narrative is informed through context clues and vague dialogue. Why do you think it was important for the narrative to be presented that way?

I just think that so much art these days made by young people or for young people is so in-your-face and always very edgy and out there. I think that’s totally cool, but I wanted to have a refreshing sensibility for my generation and I wanted to evoke more of a nuance in terms of the sensitivity of dialogue and how to approach things, and really ask the viewer to slow down. That was a really big thing for me. To be honest it’s something I’ve been chasing for so long, this type of feeling.

Does the overarching theme of grief and mourning derive from personal loss? What drives you to write and direct films of this nature?

I never thought the film was a film about grief, but I really thought it was a film about love and what it means to live without it. That’s always how I wanted to approach it. I know on the surface it’s a film about grief, but to me it’s about finding love in new forms. It’s a film about reawakenings, and finding new outlooks on life, and what happens after loss.