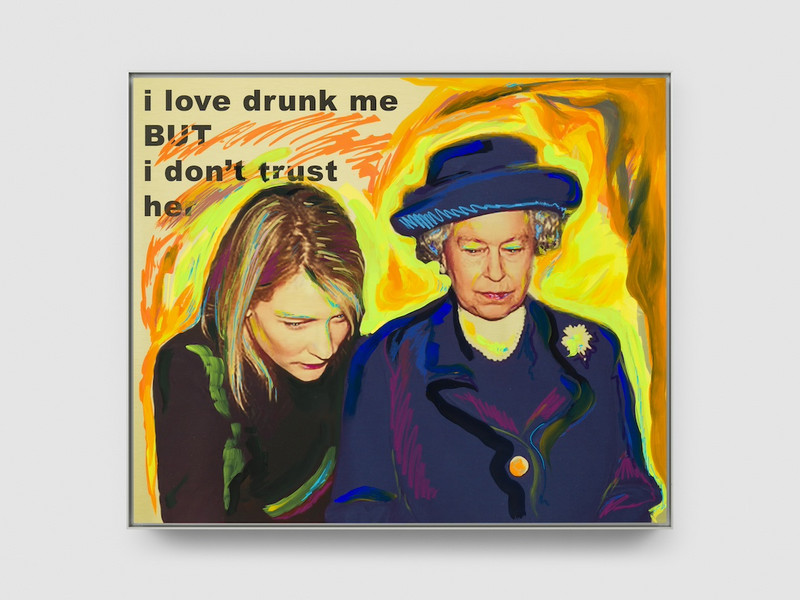

Did you learn anything specifically about femininity from your work on Girls' Night?

The book really reminded me of how important female friends are, and how essential it is to have a good group of people around you. I think girls can get a bad rep for being bitchy, but the ones that I photograph are all so lovely to each other. This new generation is really aware of mental health whereas when I was a teenager, people didn't realize that being mean was a bad thing. Now, people are a lot more supportive of each other, which I think is amazing. Also, when I was in some of the girls’ bedrooms, they would talk about boys, but they wouldn't talk about them as if they were chasing after them. They were talking like, if I kiss this guy, it happens, whatever. They weren't obsessing over them, which I found really interesting and different from when I was their age. They seemed like they had the control.

How did you manage to capture such vulnerability in your work? None of the images feel performative.

Some of the girls were a bit harder to get to relax, but most of them forgot I was there pretty quickly. The people in the photos were real groups of friends meeting up after school; I was just an addition to their night out. Sometimes we’d chat while they were getting ready, but most of the time, I’d say, “pretend I’m not here”, and then I’d snap away. They don’t get to hang out much because they’re in school all the time, so they were busy catching up with each other. At the clubs, I’d do laps to make sure everyone saw me, smiling, and trying to look welcoming. During the first hour, people were usually too on edge for photos, but once they got used to me, I could capture those more intimate moments.

Do you think the backdrop of the current economic crisis influences how we romanticize those moments from our youth?

Nostalgia is always a powerful feeling, and it’s something that resonates with me in other people’s work — it’s an important part of art and films. With my project, teenage girls haven’t been documented solely like this before, and that’s what resonates with people. There’s this view of youth culture, especially boyhood, in a Trainspotting way, where boys are being bold and running around. Because of this, I wanted to show that girlhood has its own exciting aspects. I tried to create a realistic look at growing up as a girl in Ireland, and those feelings of transition connect with everyone. Your photography captures that tension between the carefree aspects of our teen years and the approaching realities of adulthood. That transition is really apparent in the awkwardness of the girls’ poses and stances. In my photos, they seem unaware of the impending weight of becoming a woman. They’re so confident while getting ready and heading to the discos, but once there, they’re so insecure.

My friends and I were so eager to be older at that age.

It’s fun to be excited about getting older — why not? At 13, 14, 15, going out is the best thing ever. It’s when you’re 16 or 17 that things get more complicated, going out isn’t the same, and you become very conscious of how you look. The younger girls, though, are wearing a dress and makeup for the first time, so they just think they look amazing.

I also noticed you cut the boys out of the picture. Why?

When I was a teenager, the only bad experiences I had were because of boys. A lot of my insecurities stemmed from them being mean; I never had those issues with my girlfriends. I was always a confident kid, but around 16, boys really broke me, and left me with a bad feeling about that age. Because of that, I wanted to focus on the good parts of my teenage years — picking out dresses, doing hair and makeup with my girls — and cut the boys out.