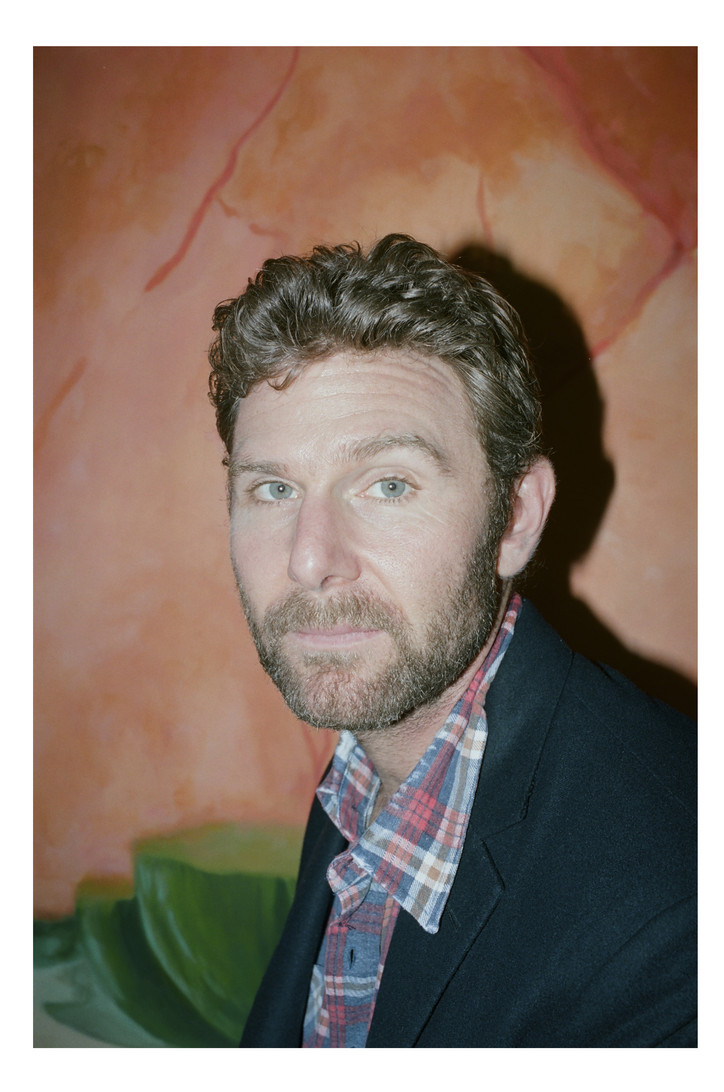

Dan Colen, Desertscapes & Wile E. Coyote

But Dan Colen has grown up a lot since he was the enfant terrible of Lower Manhattan. High Noon, for example, is a series of meticulously painted desert landscapes that individually took over four years to create.

At his studio, the guy who almost everyone has, at one point or another, seen naked (if not IRL, at least in McGinley’s photos or the artist’s 2017 exhibition, Livin and Dyin), was dressed in a button-up, jeans and loafers, surrounded by the large-scale desertscapes. He wasn’t hungover; in fact, he was beyond alert, and we spent hours talking about his painstaking process, and the conceptual nature with which he now views his work. And though this Dan Colen might seem like a far cry from the one we’ve all read about in articles profiling the noughties New York art scene, that punk rock, no fucks, teenage essence is still there—even if it’s buried under four years of paint. After all, all the works in High Noon were inspired by Roadrunner and Wile E. Coyote. And much like the paintings protagonist, Colen will just keep going.

Tell me about your latest exhibition, High Noon.

I think these paintings are, in a lot of ways, some of the most specifically made paintings in the world. I’m trying to make paintings that one person themselves can’t paint and I think the best place for me to be, is not inside of them. I spend a lot of time talking to all of the people that I work with and working through all of the different phases of the project. The way I work is never from a position of mastery—it’s really from a position of wanting to learn, still. I look at my art-making as an educational experience and painting for me is really about exploration and discovery. So, to make the scope unique you need to be 100% focused on experimenting. I mean, the paintings that you’re seeing here take four years to make, so it’s complicated and certain things get lost in translation.

Four years? Why so long?

Something like this isn’t about rendering—it’s not about copying an image. Often in the past, I’ve rendered things, so it was me trying to replicate things with paint. But these paintings are really about materialism—materialism takes precedence over the image, and material really guides us. The image is almost like a scaffolding for the painting. Like, the image is there, the composition is there—it’s easy to turn a projector on and get that. That happens in a week. But then, for 12 to 20 months following that, we search the painting with material to try to get the material to do something else. It’s very subtle but that is how we started this series.

How did the material—in this case, oil paint—end up informing your process, then?

The images in a way are so simple and monochromatic, there’s very few shapes, there are very few differences and different things in the images—it’s just a wall, sand and a road. The figuration is blatant, and obvious, but I paint them in a much more abstract way than I have done anything in a long while. Even a word like render—I’m using it in a very specific way, but I don’t ever usually paint to help describe what sand looks like, or what a rock wall looks like. Looking at the gray area in the paintings—none of them were actually informed by a gravel or tar road. So, the paint is only there to represent itself. You interpret the quality of the image because of composition and some color—it has nothing to do with how I applied the layers, or how, if I tried to use paint to replicate the source or the subject. The paint is never meant to describe anything other than itself—it’s only in the composition that we are describing a thing.

In that way, the act of making them was very abstract, because nothing figurative actually helps us know how to put the paint onto the surface. That said, there’s another body of work I started around the same time called Purgatory Paintings, that are a little more abstract—they’re essentially pictures of clouds, or pictures of the heavens, and that is kind of the flip side of the coin to the process here. They’re very different, but I like to think of them as opposite sides of the same coin. Clouds, which are essentially vapor, and I spray oil paint—so I’m basically painting pictures of vapor with vapor. But here, the reason the surfaces have this sort of waxy, map-like quality, is because we paint with the minimum possible amount of oil in the paint. So, the paint is very much like mud, like the actual subjects we are painting. That made me feel like I didn’t need to be concerned if I’m painting totally true to the rock surface, because it is rock—I’m painting with rocks and dirt. So, it’s already there—I’m far more interested in that than the final rendering of a mountain, or whatever.

Right. Did working with a team help you focus more on the process than the result?

When the goal becomes what the paint is supposed to accomplish, which is kind of very open-ended but also very ambitious—it’s in the faith that this mud can be put on there to represent this image of mud. There are so many ways to explore that idea of how to get at the essence of the material, that doing that with this team has been a very effective way for me to do that. It’s just more hands, more minds, and so much of it is about experimentation and the process—trying to keep it as open as possible.

I’m familiar with this series because I read about it before coming to your studio. But this does feel like a departure from a lot of your previous work. I know it’s cliché, but for many years, you were sort of looked at like a ‘bad boy’ of the art world, and now you’re presenting something that, in a lot of ways, is very serious, and also very conceptual.

I know. Yeah. I mean, for me, those are almost like two separate things. Regardless, I connect to it and I do know that people still have this kind of impression of me from a decade ago, which is fine, because it’s a part of me, so I have no real problem with it. All of our histories are so important to us—I’m interested in my history way beyond that, even before my birth. But also, I haven’t really painted in a focused way for many years. So, I’ve been working in a much more straightforwardly experimental way with much less traditional materials and in genres that I’m totally unfamiliar with. Here, I’m trying to create new experiences with this material, but the process is a more refined thing because of my relationship to painting. So, I am trying to apply a lot of that, the experiences I had in that discomfort, or the unknowing, to this project. But yeah, I think that there are these three bodies of oil paintings that I have been working on for the last four years and I do see them as this new level of mature work, or part of a new phase of my practice, for sure.

In what ways did you end up experimenting throughout the creation of the Desert landscapes?

The paintings are really about the accumulation of ideas, and the accumulation of materials. I’ve never really made paintings with so many boundaries, or rules. The kind of basic premise of them is that impasto, or using a thick glob of paint, is misleading. When people see a thick glob of paint in a De Kooning, or in Bacon or something, they think, ‘Oh wow! That’s paint right there!’ But really, it could be cottage cheese, or it could be hair gel, because it’s a form, a three dimensional thing. In that, all of the subtlety of what actual paint and pigment is, is lost, because it really could be anything. So, what I’m trying to do with these, and why they took so long, is because we are trying to figure out how to get this very thick paint onto the canvas in a very, very thin and even way.

The whole process sounds incredibly meticulous—especially compared to some of your other work.

Definitely, and definitely the way we used the tools is even more so. But I do get a little nervous getting too much into the formal dialogue because I think the experience is a lot bigger than that. But that really is how they’re made—that kind of obsessive relationships to the material. I hope that, whether somebody recognizes it or not, because of that, it really has the potential to slow down the viewing process, which then has the potential of changing the experience and the ideas I’m trying to explore beyond the formal ones.

Why desertscapes, though? From what you’re saying about the final rendering being the least important part of these paintings, why these colors and shapes, then?

The images all come from Wile E. Coyote and Roadrunner cartoons, which even more so than just deserts, is a really specific reference point. I have a real affinity and an affection for Wile E. Coyote’s narrative—there’s something I relate to about it, something I find inspiring about it. But more importantly, this is something I want to discuss at this point. He lives in the desert but it still happens that I think that the desert is a great place and a great subject to connect to his narrative. All of these things really connect well with the how I try to use the paint.

All my paintings in the past came from illusionism—trompe l’oeil painting, photorealism painting—in which I tried to use the paint to convincingly trick the viewer into thinking that they are looking at something different than what they’re actually looking at. So, the paint was always made to represent something other than itself. But what I wanted the paint to do was only describe itself. So, in a way, these paintings become very opaque.

I think they push the viewer out, even though they’re set up like backdrops, so you can stand in front of them. But you don’t actually think about going into them—there’s no depth of feeling, no sense of atmosphere. In the past, I feel like I set up so much of a wall—all my paintings were really about setting up some kind of atmosphere, or a luminosity, which lets you imagine you can step into them. But with these, I’m using the paint in a way to try and block you out. But I’m also using the paint in a very delicate way. So, I feel like I want to talk about the paint only being itself, and that only being itself, but that having an infinite amount of qualities. So, it is limited but it’s also so infinite. Those two things, side by side—that contradiction is something I’m interested in and I think Wile E. Coyote, he has this other interesting thing that exists simultaneously where he fails hard—I mean, he either gets exploded, or destroyed—

Or an anvil is dropped on him.

Right. But then he just stands back up and is able to reactivate all of his mischievous ambitions immediately. It’s so immediate that it’s simultaneous, and I love that he has that. As for the desert, just as a place, I really love, but I think it was just so perfect for this project because it can be so punishing, but also so healing. It’s a matter of perspective or perception or whatever, but it really can be both of those things—you can just turn around and it can destroy you, then you can turn the other way and let it refuel you.

Did you grow up watching Wile E. Coyote?

Yeah, but I don’t know if that’s the reason I became fascinated with it. The way it made its way into my work was through like a sculpture I was working on that was really about my interest in trompe l’oeil and taking something that’s really, truly two-dimensional—even in the way it’s rendered—and thinking, ‘How the fuck would I even describe this in three dimensions?’ There have been a couple different artists that have drown Wile E. over the years, so I was looking at all the episodes and tried to see if I could get any hints from different moments in it, and just watching him getting destroyed over and over again was just really amazing and I got really into it. So, I started making these little lookbooks of him like, falling, or something falling on him, and then suddenly I had this collection where I started wanting to take him out of those moments and thinking about that space, that space where both the utter failure, but also the rejuvenation and ambition happens. I started noticing that that space is actually a really spiritual one, it’s the desert. I’m also a big Georgia O’Keefe fan.

With most of my work, I don’t think as directly from a specific work or group of works as these do. I mean, I usually look at a lot of things and it kind of all sinks in. But these paintings are in a way really specifically about my relationship to Georgia O’Keefe, Brice Marden and John McCracken who are three very different artists in so many ways. Marden, I associate him with the landscapes that he puts himself into to make a painting—not necessarily a desert, but regardless, the fact that the landscape seeps into the work in a very direct way; then McCracken and O’Keefe, I think about them in the desert. All three of them I almost feel like spirituality is weirdly something that a lot of artist stay away from talking about, which seems a little backwards to me. I mean, I have been there and I get it, but for me, it’s really important that it’s a part of the conversation and it’s a part of the work. I think all three of those artists have never really shied away from it too, and I really enjoy that.

Right. Like how people say, ‘No politics or religion at the dinner table.’ But now, because of the current climate, everyone does talk about politics. But religion—or spirituality—still seem pretty much off limits.

It’s strange. I remember a defining moment for me was—David Hammons is an artist I really relate to, and I was reading an interview with him, where this woman interviewed him, and he was talking about spirituality, and it occurred to me that I hadn’t read one of my heroes or even an artist that I admire, ever talk about it so directly. And I’d never thought about it before, but I feel like, in that moment I realized I also wanted to address it directly, like he was, not accidently, but purposely, for sure.

But other than the fact that these paintings represent the desert, and the desert can be a spiritual place, how are you addressing that with this series?

I believe all art-making is spiritual—in doing so, you are in the realm of the spirits, in some way or another. A big challenge for me since my very first projects, because with all of my work, part of my practice has always incorporated some kind of durational effort. My first show was these paintings that took me a very long time to make, and it’s not because that’s what I enjoy, or even because the work needs it. It’s usually because I don’t know what the fuck I am doing, and I’m not very good at it. But I’m committed to it, so I’m willing to stick it out and really learn. Over time, I decided that there’s actually a quality to the touch that happens, or the evidence that’s left behind by that education. What becomes more and more important is to start out with an idea, and of course, the finished art can’t actually can be about that idea—that would be so silly if I spent two years to present an idea when I could’ve just stood there and said or something. So, what has to be important is what’s happened in the meantime—some of it I can identify and some of it I can articulate, but some of it just happened. I do think that these things can communicate their own experience of that time.

Like I said earlier, it’s important for me to talk about the formal aspects because I think the formal aspects are what slow down the viewing process. I think a lot of it is really about just that sentiment of, ‘Can I stand in front of anything and consider it for the time it deserves?’ None of us give the time to anything—our taxes, or children. The world is just so fast paced, so busy—but especially for something without purpose. So, I think there’s a real spirituality in stopping and giving something that time that really has no reason to be given that time to.

Definitely, and there’s obviously a spiritual aspect to art-making in general, as you said. But when you’re working on something—especially something that takes this long—where the end, or the finished product, isn’t really the goal, the process, or the project itself sort of has to become spiritual. Otherwise, it’s like, ‘Why the hell am I still doing this?’

Definitely. The way you described that is very similar to how I would. But especially over the years, because I used to really think that that first idea was very important, and it was in my mind, and I could see it, and then I would try to force the painting or the object to be a replication to that. Then I sort of realized, ‘Wait a second, I am just not that great.’ Like, I can start something, but it’s so important that it can catch other things and allow for other things to come in, as well. So, my paintings become much more abstract in how I actually touch them, how the paint gets on there, because I want more than what’s in my mind to guide it forward. Hopefully, you do get to that point where it’s like, ‘Yes! That is the thing,’ but nobody ever knew what that thing was, until it presented itself. Because of that, it forms outside me, and outside of my mind, and that is spiritual in a way—I am essentially trusting the process, the environment, the influence, and all of these other people. But even when I was working by myself, or with a smaller team, and I started thinking about these things, I really realized that it’s just about the temperature, or the space that you give yourself, and the environment that you are in, or how you come to it that day – all of these different things influence it.

That’s an interesting concept. But I think it’s not so much about the fact that you can’t replicate your ideas because of your skill level, than it is the fact that the ideas in our heads just can’t be done. I feel like it can never really come out like you plan in your mind.

Exactly. It’s impossible! What’s in a mind can’t be in actuality—those are two different spaces, they’re two different realities. The beauty of it is, is that once I am getting released from that, then I can actually get to the great thing. But if I’m trying to make something that’s impossible, it’s just always going to be a let down, or a missed opportunity.

But that’s one of the hardest things—to give up that control of how you wanted it to be, or how you thought it should look.

Oh totally. I was talking to somebody else about this body of work and talking about ideas about taking risks, or working in the space where you don’t know what the end result will be. They kind of associated that kind of risk-taking as part of my practice, but I incorporated that into my practice to save me from myself because really, what I am is over-meticulous, over-perfectionistic, and I’m really connected to trying to reproduce this thing that I see so clearly, but will never actually come outside my mind. Then, over time, I can see that it’s not even worth it—it’s not even worth it to fucking try. Even if I could do it, it’s not even worth it, because to allow all these other influences that makes it infinitely more interesting, and more profound.

So, you’re not usually a risk taker when it comes to your work? I’d think that would be surprising to a lot of people.

No, that’s the thing—I am usually a risk taker, but it’s not my instinct. After my first show, I immediately saw a lot. It was mostly because I wasn’t sensitive enough to understand my own flaws, in a way. But I saw that the audience wasn’t seeing what I wanted them to see, so it changed my relationship to my practice a little bit, and that allowed me to get to this place where I realized that I need to be working out of places of discomfort. It’s just like life—the unknown is where the beauty is. But we’re always looking for security and stability. So, to keep myself in a place where I’m working from an unknown space is incredibly important. It might not be my instinct, but I am always trying to push myself back over there.

The conceptual area between 2D and 3D in these paintings is fascinating to me. In a lot of ways, the works feel totally 2D—almost like a backdrop from a movie set. As opposed to some of your other work that, like you said, feels much more atmospheric, these pieces really stand on their own.

Yeah, it’s funny because there are a lot of little weird contradictions built into that view. I totally agree with what you are saying, but the way I talk about these, or the way I think about them, is less as images and more as objects, although the object is a flat surface, or essentially a box. But I think about the object of the paint, and what that is, as opposed to these other things that you’re talking about, which almost negate the paint as material and open up a fantasy space. Then all of a sudden, they almost become less 2D, because you have this illusionistic space. So, when you figure out the illusionism, they become very flat.

But what these paintings connect most to, and kind of distant part of my practice, has a lot to do with how I started thinking about sculpture, and how these different realms of realities, or these different dimensions—like the Birdshit Paintings. I was making them really at the same time I was making the gum pieces, and illusionism got really twisted in them for the first time for me. So, I was making paintings that look like AbEx paintings, with bubblegum, and I was using oil paint to make a wall of substance that looked like bird shit. But what I realized was that it is illusionism—the Birdshit Paintings are actually sculptures, they are not illusionistic paintings, because they are dimensionally accurate to bird shit. Again, I am not using the paint to actually render anything—I am using it to actually be a material, to take the form of that material. So, if I were to paint a drop of bird shit, it would look totally different than an actual drop of bird shit.

So, the idea of paint as an object was inspiring, and I didn’t know what to do with it. In there, it was illusionism, but there was no rendering. These, in this very weird way, and in taking on this ultra flat consideration, are just as much about the material as those Birdshit Paintings. Neither of them allow the viewer to cleanly focus on that, they are both kind of slippery in a way. But the paint is first in both of them. I had been trying to apply that to a figurative image since then, and it has been very hard. So, I think this is really the first time that I’m really getting at that.

Let’s rewind a bit. Was painting something you’ve always done? Like, even when you were at RISD?

I have always drawn, and I was able to go to college because I had always drawn, and could draw very well, and because I enjoyed drawing. I also did outside of schooling. Anything inside schooling was always difficult for me, so I was able to develop it more like that.

Right. It’s always more fun when you’re doing it outside of the rules.

Yeah, I was just always resistant. I have a pathetic authority complex—I’ve always been plagued with that. But so, I did do a little bit of painting in high school, but I didn’t have the time to be comfortable with it. I probably made three paintings in Arts Students League. Then, I went to college. I was searching to find my voice and pretty quickly I decided I wanted to take all of my hand out of the work. I started spraying pretty soon after—I didn’t want to use a brush, I didn’t really want anything to do with a brush, and I just started spraying and stenciling and using a lot of different alternative and more industrial techniques. That first body of work that I talked about earlier—the show was called Seven Days Always Seemed Like A Bit Of An Exaggeration—I started it by spraying right when I got out school—it was my first show after school. But I started with spraying, and I kind of knew that it wasn’t going to work because I wasn’t very good at it, but I got far enough into it that I had to find a way to figure it out, and realized I was going to have to paint it.

Those two years is really when I learned to paint. I called up every friend at school that I knew was painting seriously, and asked them like, ‘How the fuck do you do this?’ Someone said, ‘You have to go to The Met and paint every day. Unless you get the fanciest brushes, you are going to be at a handicap to everybody.’ So, I got a couple of different things like that, and I kind of got set up and then I just started painting. That is my beginning and what I was doing in school, so I do think of it as being at the core of my practice—oil painting—and I did do what my friend said, and started going to The Met every week and painting every day. It was an amazing time and hopefully I’ll find another time in my life to be able to do something like that again, because just to kind of be a viewer, and indulge in that, in a very intense way—it’s so powerful.

I was going to ask you about working in different mediums, like painting versus sculpture, but I’m hesitant to call the medium in this series painting—in a lot of ways, it’s not the medium, bur rather the art itself.

As much as I want it all to be fluid, the painting happens to—I don’t think it’s my intention—but it becomes more of a sacred space, in a way. I am, in a way, willing to negate, or disrupt the focus on content, or themes, or things that are important for me to say, to let the material, speak and to let the experience be a much subtler thing, just because I believe that something mysterious and worthwhile happens in that space, where I use some of the sculptural, and now performative works, to explore more blatant themes or issues. But at the end of the day, what I want is to start with an idea and give myself the space to find the best material to use, to explore that idea and then give the space for that idea to totally transform once I start interacting with that material. And that’s true with painting, or whatever over medium I’m working in.

Do you feel like there is a through-line throughout your career, or certain themes you always find yourself revisiting in your work?

I really do think of it’s this idea of experimentation, exploration and the unknown is something that is always tying things together for me. It is diverse in a way and I am another consistent part of it. The work ends up, at least in my mind, engaging global ideas and global conversations, but it never starts there—it always starts with my personal experience. So, for me, that’s something I do think about a lot. And it’s a dilemma to make work about myself—I often question that. But since, I’m resigned to that in a way, and also the fact that I feel everything is connected and you can get global from a microscope. But there is a dilemma in just indulging in that and saying, ‘I started with a feeling that I had where I felt like I didn’t know where my home was at that moment, so now the work has to do with refugees.’ But that’s how it works. It’s boundless in the same way as that is, but also as basic as that is, it all comes from me. I am not just a source, but I am the subject, too.

‘High Noon’ is on view now through December 15 at Gagosian Beverly Hills.