Chivas Clem on Cowboys, Caricatures, and Cracks in the American Dream

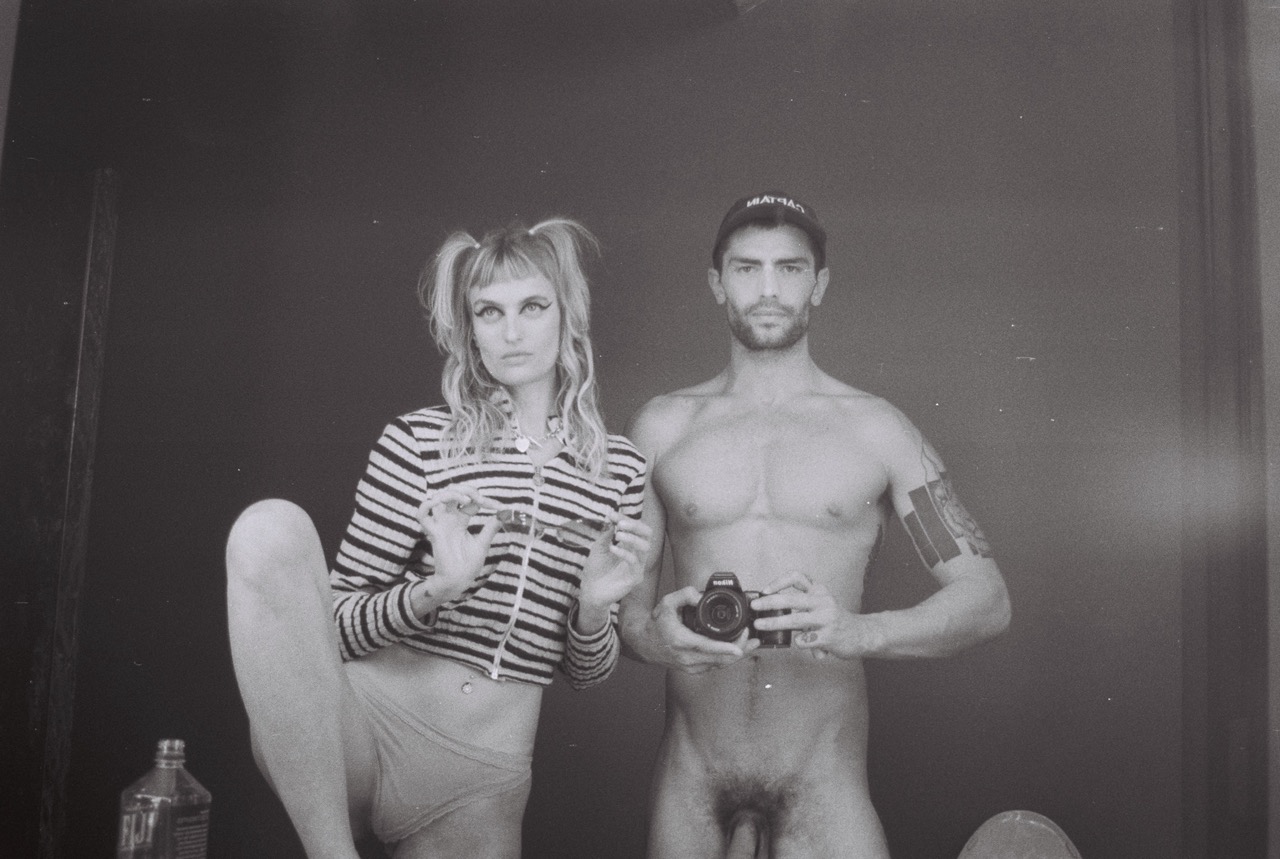

Chivas Clem, Greg with My Grandfather’s Shotgun, From Behind, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.

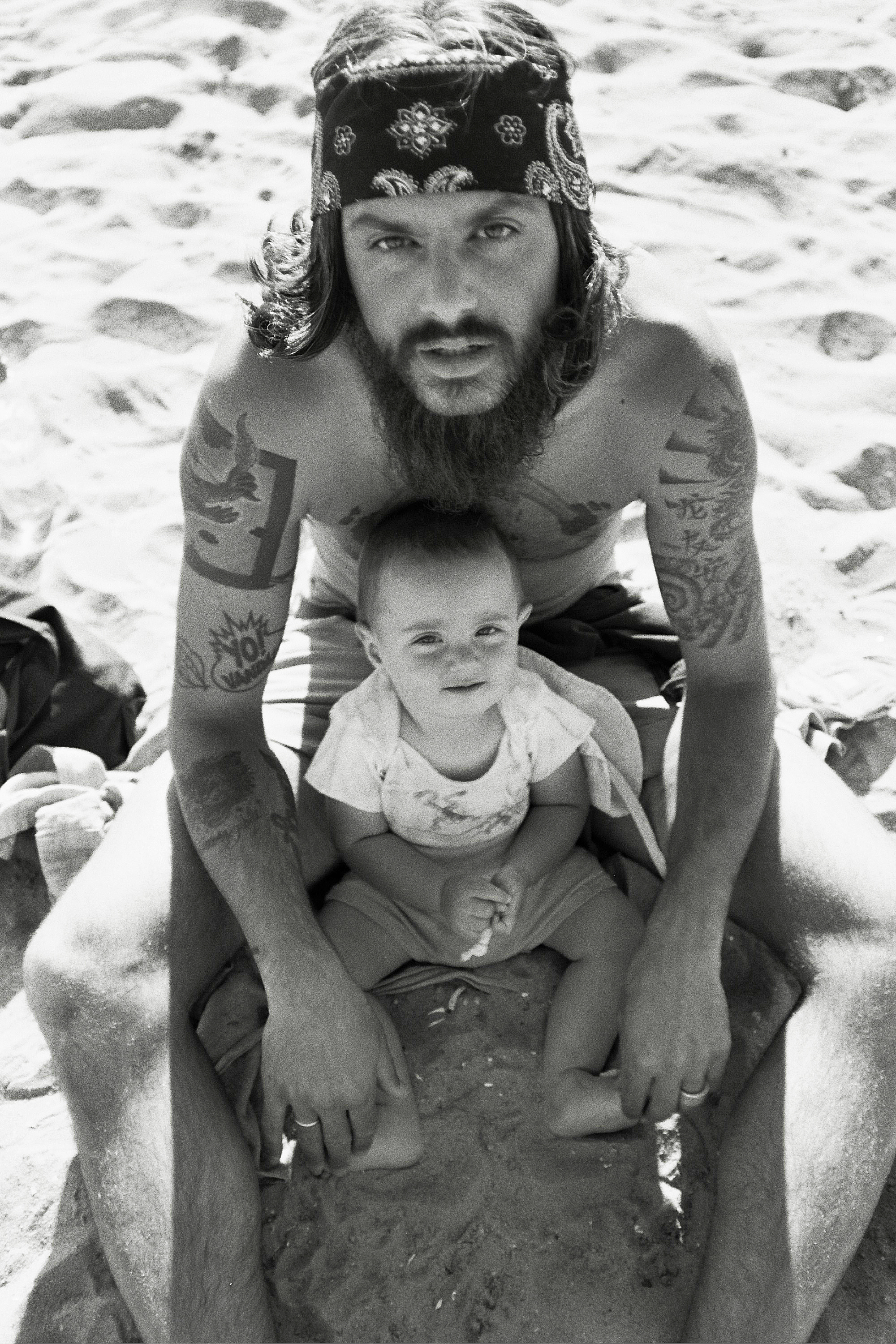

Growing up in Texas, Clem harbored a deep-seated phobia of men and boys, and his work today reflects both a confrontation with that past and an effort to dismantle the very archetypes that once terrified him. While Clem forms close relationships with his models, his approach contrasts with Clark's. Clark lived, used, and suffered alongside his subjects using, and suffering alongside them. Clem meets his models serendipitously, maintaining a careful distance as both insider and outsider. The series tackles broader American anxieties, particularly the “redneck” stereotype and its wider cultural associations. Clem offers a glimpse at the fragile humanity that persists beneath the cultural caricatures we've become indifferent to — and afraid of.

Ahead of the opening, I spoke with Clem, who called in from his weathered home-studio in Paris, Texas — the very place where many of the photographs on view were captured. We chatted about Southern masculinity, the process of meeting his models, and how his work navigates the balance between despair and innocence.

Hi Chivas, how's it going?

Chivas Clem— It’s going okay, I guess. I'm ready for summer to be over kind of.

I feel the same way.

It's miserable in Texas. It was like 113 degrees in my car the other day.

That's awful.

No, it's gotten really insane. I grew up here and when I was a kid, it was never like this. It was hot in the summer, but it wasn't like this.

I grew up in New York, and I feel like that about our summer thunderstorms. They were never as crazy as they are now.

Yeah. It's true!

When I first saw some of the photos in Shirttail Kin I had a visceral reaction, I teared up at some of them.

Oh, God. I'm so happy to hear that. People have such dramatically different reactions to the work. Occasionally I'll show the work to somebody, and they're very moved by it, even to tears, and then sometimes I show it to people and they see it as soft-core pornography.

I had a show in Houston a couple of years ago with Bill Arning, and Bill caught this guy masturbating in the gallery, which is kind of flattering in a way. I mean, I can't imagine that happening at David Zwirner.

Yeah, probably not. I didn't view the photographs as pornographic. What resonated most was the act of seeing these men, depicting them through your lens, and now, exhibiting the images in a show at Dallas Contemporary. There’s this American subculture that’s deeply marginalized and this project, its placement, defies that.

People don't talk about that with the work that often, but it is very much about them feeling seen. A huge part of my work is building this sense of intimacy with them so that they’re comfortable with me. It all happens very organically, I've never done a formal audition or anything, and they're all just local people that I've met. I met one of them at a gas station, and another while hitchhiking, and I’ve cultivated friendships with all of them. A lot of them sit for me over and over again.

Having grown up in a place where masculinity was rigidly defined and often weaponized, how do you think your Texan roots shaped not only your artistic lens but also your understanding of the men you document in Shirttail Kin? Does the work, in a sense, reflect your own reconciliation with that past?

Well, when I was a child I actually developed a terrible fear of men and boys, so severe that I actually had a therapist who wrote a note to the school that I could not take boys’ phys ed so I was transferred through junior high as a girl for a few years, which was very confusing for everybody but me. I couldn’t step into the boys’ locker room without having a meltdown.

I grew up around rednecks and had this terrible fear and fascination for them. And erotic fixation, which I didn’t discover until later on. I still live in the country north of Dallas, and that’s still how everybody here is.

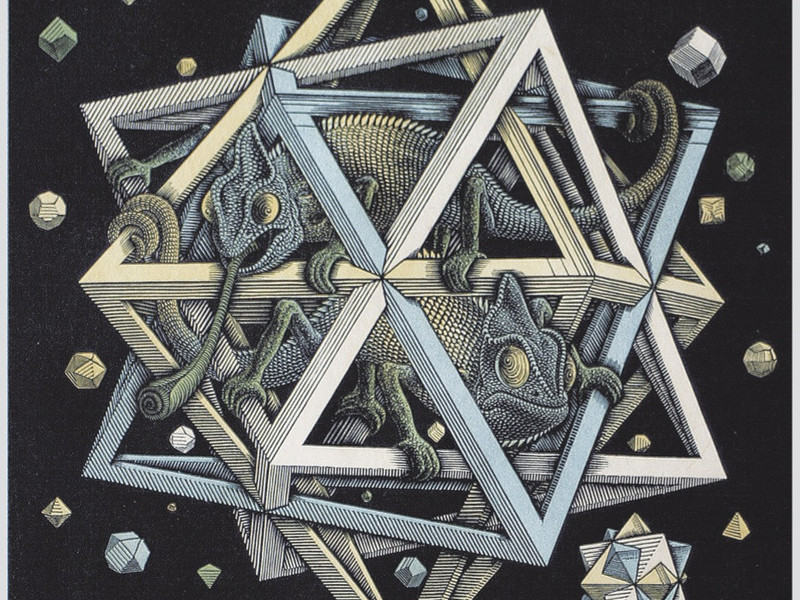

America is witnessing a crisis of masculinity right now, which has been growing since the women’s movement and the gay rights movement. There’s this hysteria amongst the right over men who dress in drag that it’s some kind of humiliation ritual. I wanted to look at old-fashioned masculinity with a fresh set of eyes. What I found here is that these men are really wearing their own king of drag, clinging to their own understanding of masculinity. That was very interesting to me.

There’s a long history of photographers who have looked at cowboy archetypes, like Danny Lyons and Larry Clark, but I feel like that archetype’s dated now — it’s not as relevant. There aren’t any real cowboys anymore; it’s been reduced to an aesthetic. If the cowboy archetype represented rugged individualism, then what it’s become, if it’s the image of the redneck, is a deplorable person, racist, homophobic, all of the above.

I wanted to show the humanity in these guys. It’s funny, originally I didn’t want to call the show “Shirttail Kin.” A friend of mine said that I should call it “We Found Love in a Hopeless Place.”

Given the often deeply ingrained societal norms around masculinity that exist, especially in the rural South, how do you see their lived experiences reflecting broader cultural narratives in America today?

What people don't realize is that the living conditions are often way worse than you could imagine. You can’t imagine the environments some of my models grew up in. There’s one whose parents abandoned him in a house when he was 12, and he kept living there alone, with nowhere else to go. He had neighbors who would bring him food occasionally. Some had it way worse. And of course, they grow up filled with so much rage and anger, but also fear, so many of them are terrified. It's absolutely like witnessing the return of the repressed.

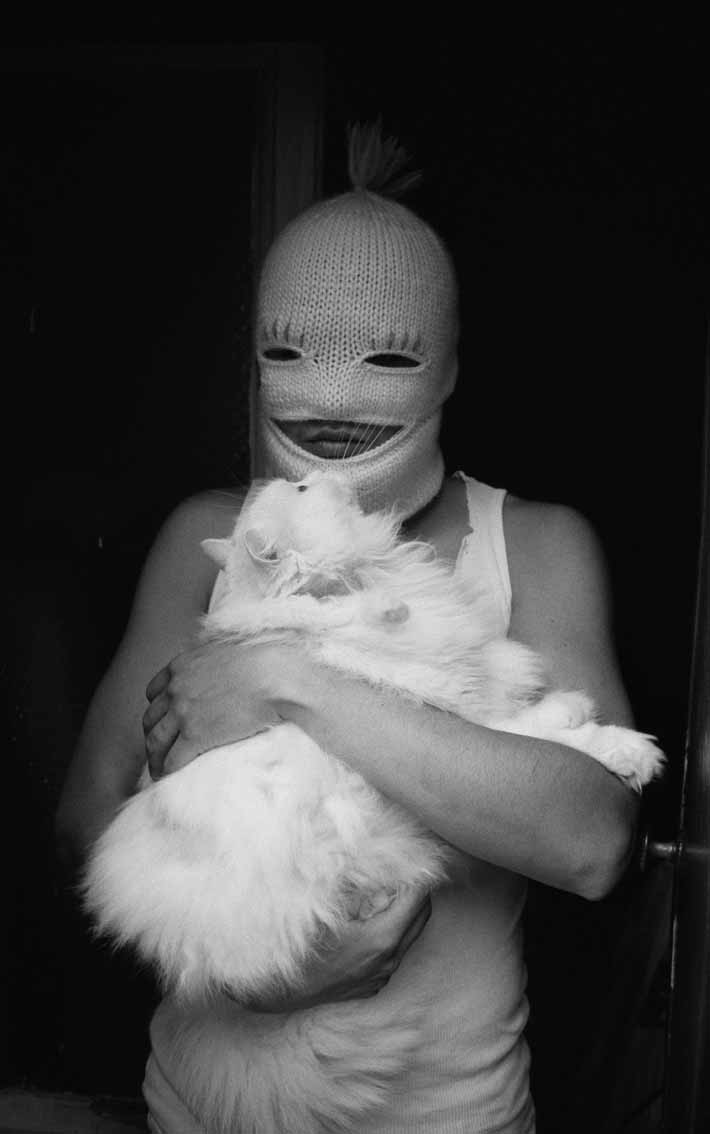

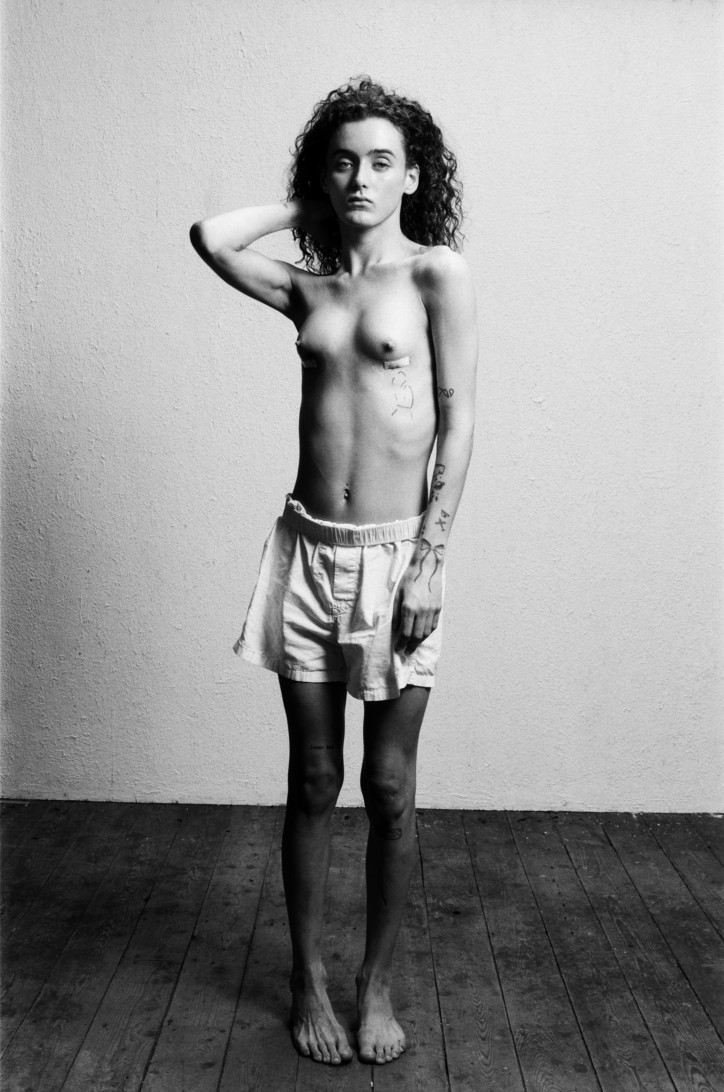

Chivas Clem, Coty in the Bathtub after Breaking In, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.

Chivas Clem, Cole in front of Chris Farley, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.

One image that stands out is the boy sitting on the staircase — there’s an almost haunting innocence in his gaze. What drew you to him in the first place?

That kid is the most sensitive. He's actually in prison right now. The reason that I met him was because he broke into my house when I was out of town. I came back and I found him in the bathtub asleep, just taking a bath. He has the kind of face that could haunt you for a thousand years.

Do you believe that, in many ways, the men you photograph are shaped by their environments — almost as if they are instruments of their own fate?

God, an instrument of your own fate. I never really thought about that, but you’re exactly right. Those are powerful words. A lot of these men are victims of their circumstances. They grow up without access to anything. I would say 60 to 70% of them are virtually illiterate, and there’s such naivety and innocence to them.

Do you find that this innocence or naivety gives them a different kind of wisdom or perspective?

There’s an interview from the ‘60s with Pasolini, and the interviewer asks, “Who are your favorite people?” And Pasolini’s response implied an admiration for the uneducated because they aren’t spoiled by petty-bourgeois ideals. It’s the same with Jean Genet, who was fascinated by criminals, viewing them as figures of innocence. He said something like, “The criminal organizes a disordered world for us.”

Given the transient and often isolated nature of the men you work with, is there a sense of camaraderie among them?

That's an interesting question. I would say that most of them are quite feral, like lone wolves, because they were never parented correctly or taught about what it means to be loved. They see relationships as transactional. They might develop a bond with somebody but it’s often fleeting. They might have to go to prison for two years, then that person finds somebody else.

If you’re barely surviving, I think it’s very difficult to create any genuine bonds. I have models that have girlfriends, but the relationships never last. And it’s always transactional. She has a check, a place to stay, or he gets a check and she stays with him. When I first started doing this, one of my models went to prison and I sent him a care package. He called me crying, and this is not somebody who cries. He said that he’d never had someone do something so nice for him in his entire life — that his mother would never. And she probably just can’t afford to.

Would you say your approach is driven more by instinct or is there a method to the scenes? How do you balance spontaneity with intention in your work?

It's all instinctual. There's no real method to it at all. Everything is very much by chance. I never plan to meet the guys I do. When I first moved back here, I was driving to my studio one day and there was a guy on the side of the road in tight white jeans, a white t-shirt, and a white cap with headphones on, moving to the beat of the music. It was so cinematic, like something out of Saturday Night Fever. He became my first model.

Photographing these men — who in some ways represent the very figures you feared growing up — have you found a new understanding of your childhood phobia?

When I started photographing them, I realized that they were just as fearful as I was as a kid, but rather than becoming hysterical, they acted outward. I guess I learned that humanity is hard to recognize in light of our own fears and prejudices. The work is about finding humanity in a subculture that is perceived as so deeply dangerous. I mean the boogeyman of American culture right now is the redneck — the deplorable right. Yet, there’s also a deep sadness and vulnerability to this figure.

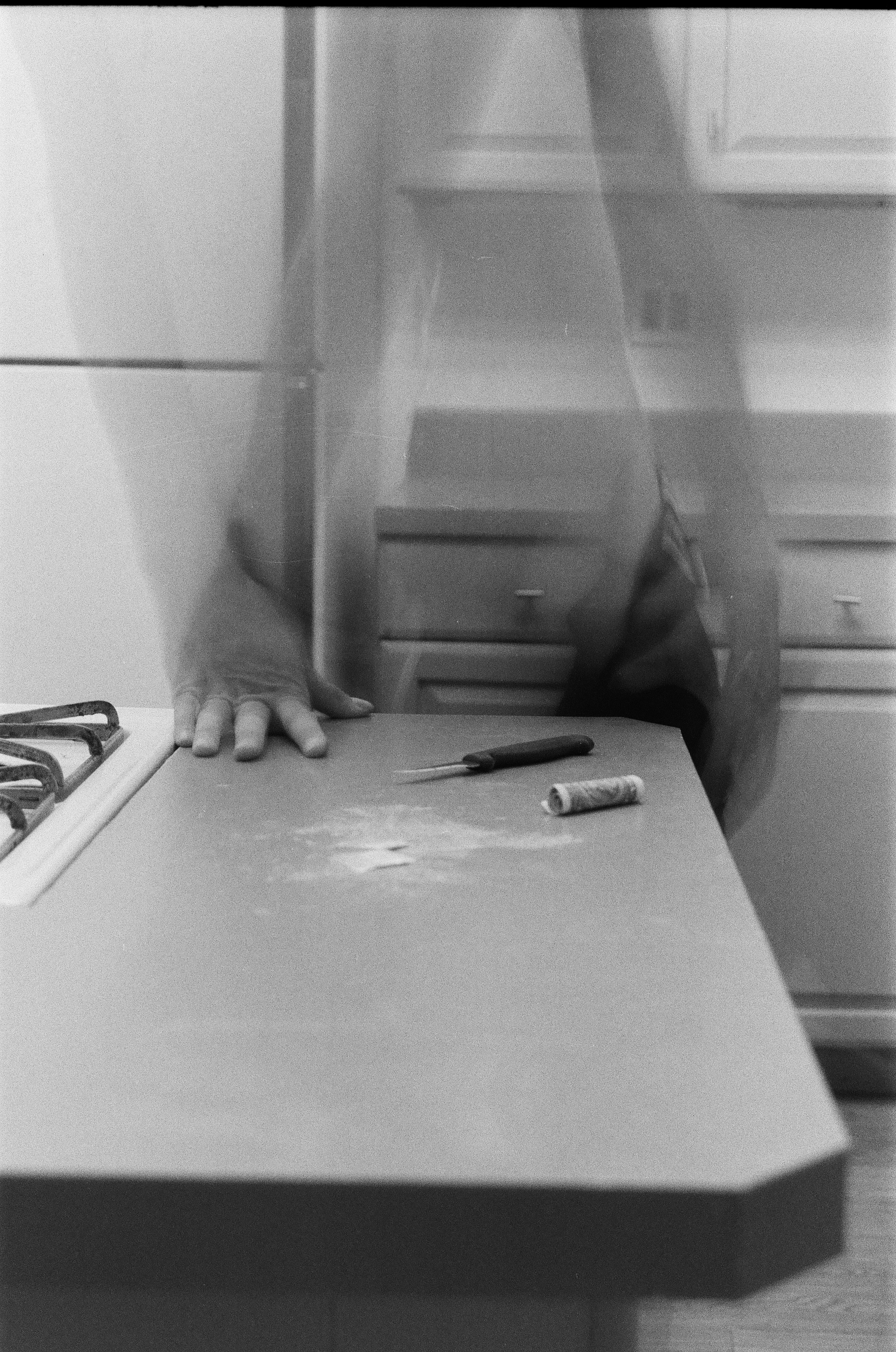

Addiction seems to lurk in the background of the lives you capture. How does the presence of drug use in the rural South inform the narratives you’re telling through your photography?

Absolutely. And there's so much despair. I mean, I was a junkie in New York, hooked on heroin. The reason that I moved back to Texas twenty years ago was to get sober and now I am. Here, people are primarily meth addicts, like crystal meth, which I think it’s way worse that opioids because it fucks with your brain chemistry in such a way. It’s very difficult to get sober from opioids, we know that, but you can, and get your head right again.

If you’ve been doing crystal meth for 10 years and get sober, I don’t know if your brain ever really recovers. A lot of these guys grew up not just impoverished and plagued by domestic abuse, but also with terrible, terrible intergenerational addiction. There’s an entire generation of kids affected by their parents’ drug use. It’s a fucking horror show really, another kind of darkness.

Like alcoholism, but worse?

Much worse. I do have a model whose mother drank while she was pregnant, and he has fetal alcohol syndrome. He kind of escaped the worst of it, but he has all these learning delays, despite being so bright and full of ideas.

Another guy who modeled for me is an incredible poet. He wrote poetry all through his jail term in Oklahoma, and he writes music — he plays the banjo and the fiddle. Under different circumstances, this guy would’ve gone to NYU and had a recording contract. He works a shitty job roofing, but he’s completely committed — he has like 30 volumes of poetry written. But he doesn’t understand how getting any of it published or recognized works.

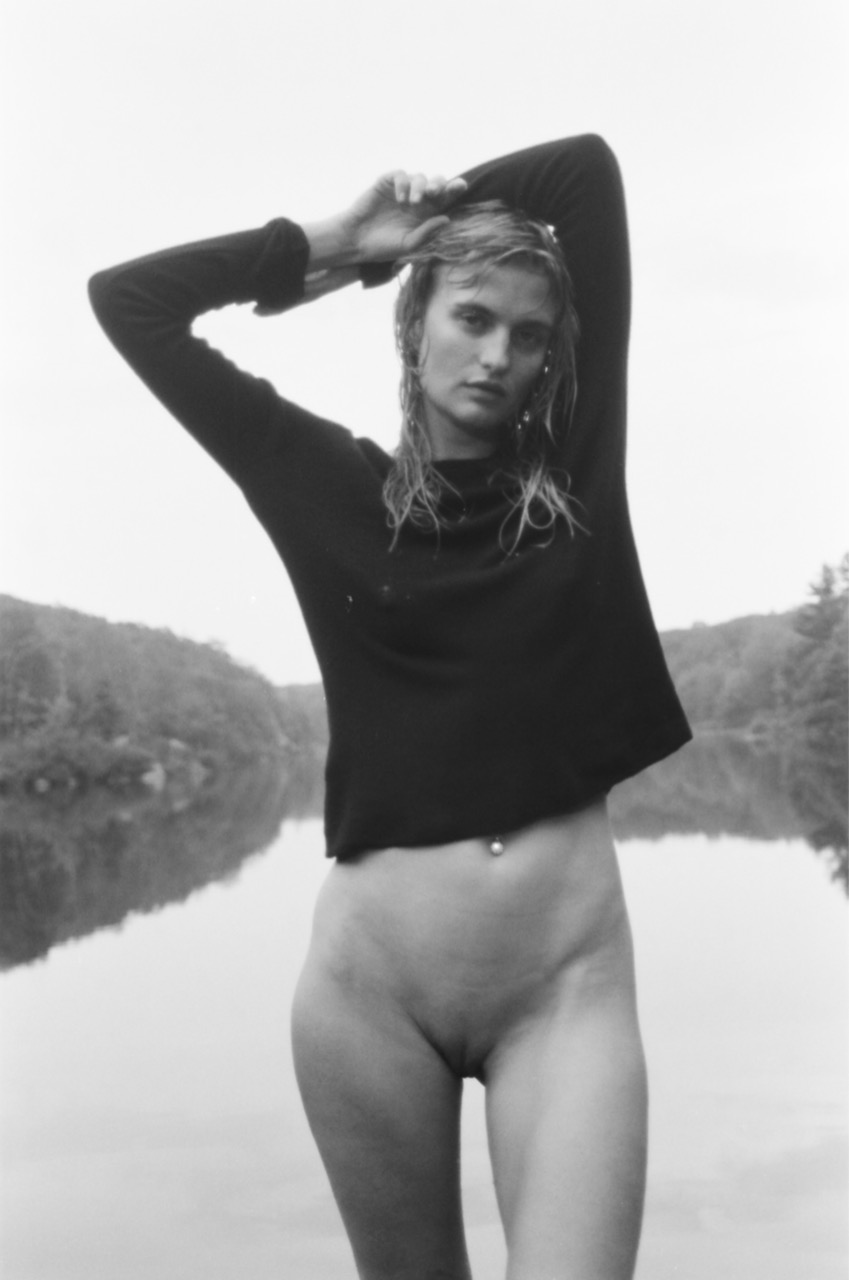

Chivas Clem, Dillon at the carwash, Night, 2020. Courtesy of the artist and Dallas Contemporary.

Much of the despair you describe seems to be rooted in a lack of access — whether it’s access to education, support, or even a path out of addiction. Do you think this lack of access, alongside the intergenerational struggles you capture, plays a central role in the stories your work tells?

Yeah, I mean it can get pretty dark down here, and I didn’t want that aspect to be overshadowed by — well, I was just reading a snippet somewhere about the work, and they immediately launched into this whole thing about queerness. I didn’t want the work to be coded in that way because none of the models identify as queer. That’s not to say that they don’t have sex with men, but that’s often transactional, and not the focus of the work.

Certainly, I’ve borrowed aesthetics from art history, like cheesecake photography, but I don’t think the work is exclusively about queerness.

Yeah, I don’t see that.

This writer called me the other day and was like, “Okay, so all of these guys are twinks.” And I was like, “What? No…”

[Laughs] I’m sorry.

That word has no real meaning here. That’s like a grand misreading, but I think that people see what they want to see through the lens of contemporary culture.

I wonder if any of the guys you’ve shot would know what a twink is.

They probably have no idea what a twink is. But yeah, you can’t control the reaction to what you put out into the world. I was reading something recently about when Larry Clark first made Tulsa. What was that, ’76 or something?

’71.

Shit. That's the year I was born. It’s interesting how mysterious that work was to people because nobody thought about addiction, the rural poor, or any of that. For a lot of his early shows, Larry exhibited alongside postmodernists like Richard Prince and Cady Noland. It wasn’t presented as photography. It was more off-the-wall than that — there was no sentimentality to it.

I wonder what the reactions to your work will be with the show being up so close to the election.

Well, the curator, Alison M. Gingeras — who is brilliant by the way — wanted the show to coincide with the election cycle because she felt that it would address the issue of Texas, which has become such a red state in recent years. Texas wasn't always a red state. I feel like we are really on a precipice, to be honest with you. People don’t understand just how dangerous things have gotten. The 2025 document that the Heritage Foundation put out is a recipe for fascism.

How has the community in Texas responded to the project?

Well, there really isn’t an art community here in Paris, Texas — it’s such a tiny town. And honestly, I don't show the work locally because it's often seen as homoerotic. When I show the work to my models, though, they all get kind of tickled by it. I think they like the idea of being seen, but they’ll sometimes say things like, “I just don’t want my grandmother to see it.” I always tell them I would never take a picture that I wouldn't show my own grandmother.

This will be the first time I’m showing the work in Texas, so it’ll be interesting to see what people think. People will probably code it, again, as homoerotic. It might be hard for them to see beyond that.