The Club Is Coming to the Stage

We enter and make our way to what is approximately front left of the DJ booth, where we’re accustomed to dancing at clubs in New York. “So is this a techno club or a dance performance?” yells an uncertain participant in my boyfriend’s ear. He laughs, bouncing along to Ben UFO, and yells back, “It’s both!” The club has long been a hot topic in European contemporary dance but it is only now making its way into New York performance venues, largely through transatlantic tours. R.O.S.E. follows recent examples like Michele Rizzo’s HIGHER xtn. at MoMA PS1 (May 2024), (LA)HORDE’s Room with a View at NYU Skirball (October 2023), and Gisèle Vienne’s Crowd at BAM (October 2022).

Do these performances compromise the club’s spirit — a space idealized for its anonymity, dark lighting, and thundering music? The notion of the club as a utopian escape is admittedly just that — an ideal — because of how its intense conditions can create barriers to entry. Still, the club remains sacred for many, a place to forge connections and embrace an alternative state of being. Looking at how performances transfer this spirit to new settings reveals what aspects of the club are essential and those that aren’t.

Eyal’s dancers make their entrance. The lighting shifts from roving blue to yellow spotlights as Ben UFO’s tracks transition to more melodic beats. Clad in deconstructed lace Dior lingerie with dark red tears painted on their faces, the dancers move cautiously in a tightly maintained pack, slicing paths through the horde with hoof-like steps and jerky leg extensions. After around ten minutes of this controlled choreography, the dancers vanish as the lighting shifts back to blue and Ben UFO picks up his dubby beats. The club, as we knew it, resumes. This cycle of tightly executed movements and free-flowing club-goers repeats several times, each time emboldening the dancers to plunge further into the crowd.

Clubbing in a building once built for the U.S. Army National Guard on Manhattan’s Upper East Side turns out to be surprisingly successful — at least for the audience. What starts as an awkward, scattered group searching for their non existent seats gradually gels into an engaged, bouncing crowd that erupts in cheers each time the dancers enter and exit. Performance patrons who might never step foot in a club find themselves swept up in its potential for communion, moving in unison with fellow ticket holders. But it isn’t until the very end of R.O.S.E. that the dancers finally break free from Eyal’s choreography and join the fired-up audience in a brief moment of improvisatory movement with the music. By keeping her dancers at arm’s length, Eyal seems more interested in the club as a backdrop for her signature movement style than wholly as a space with meaningful stories to be told.

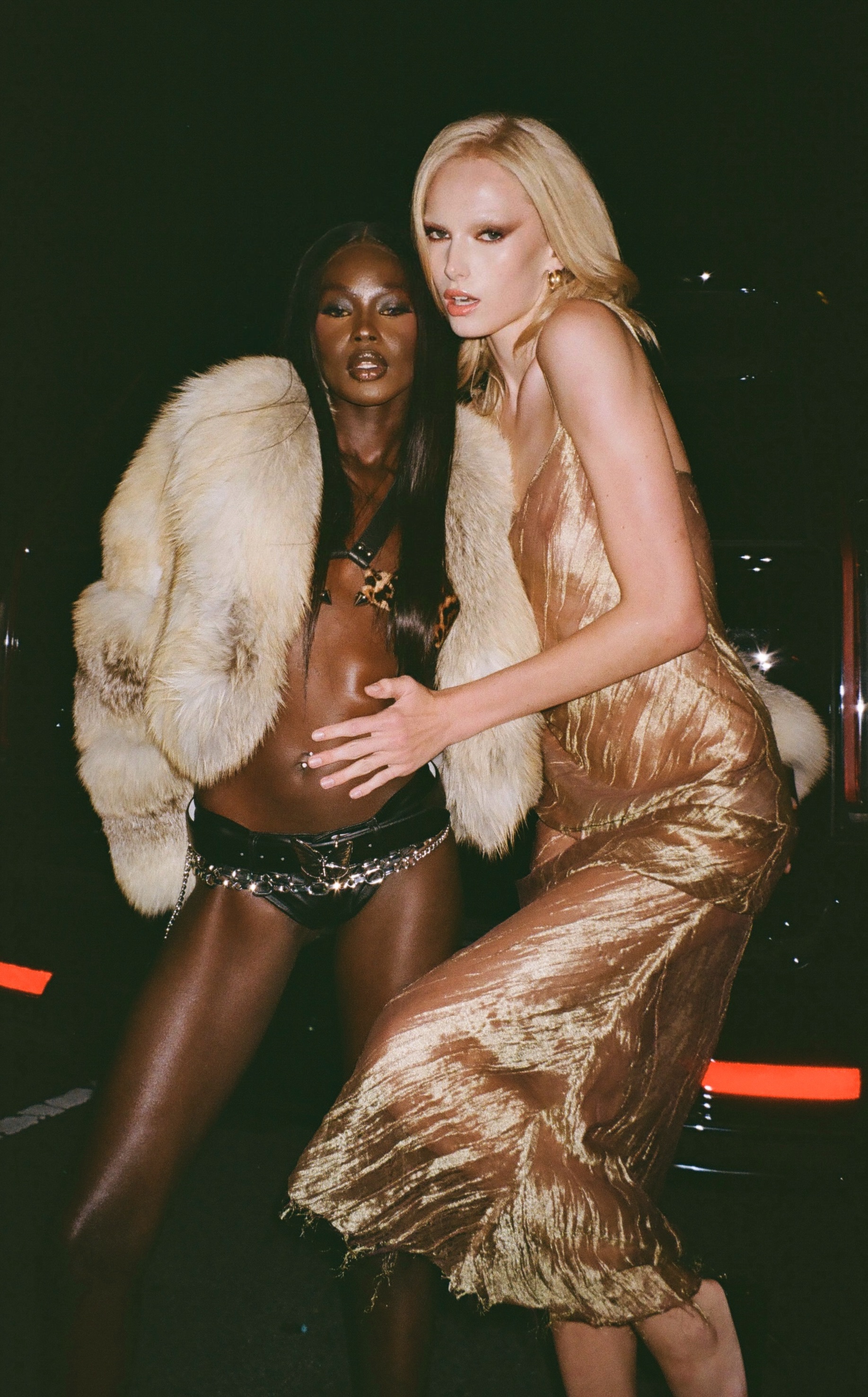

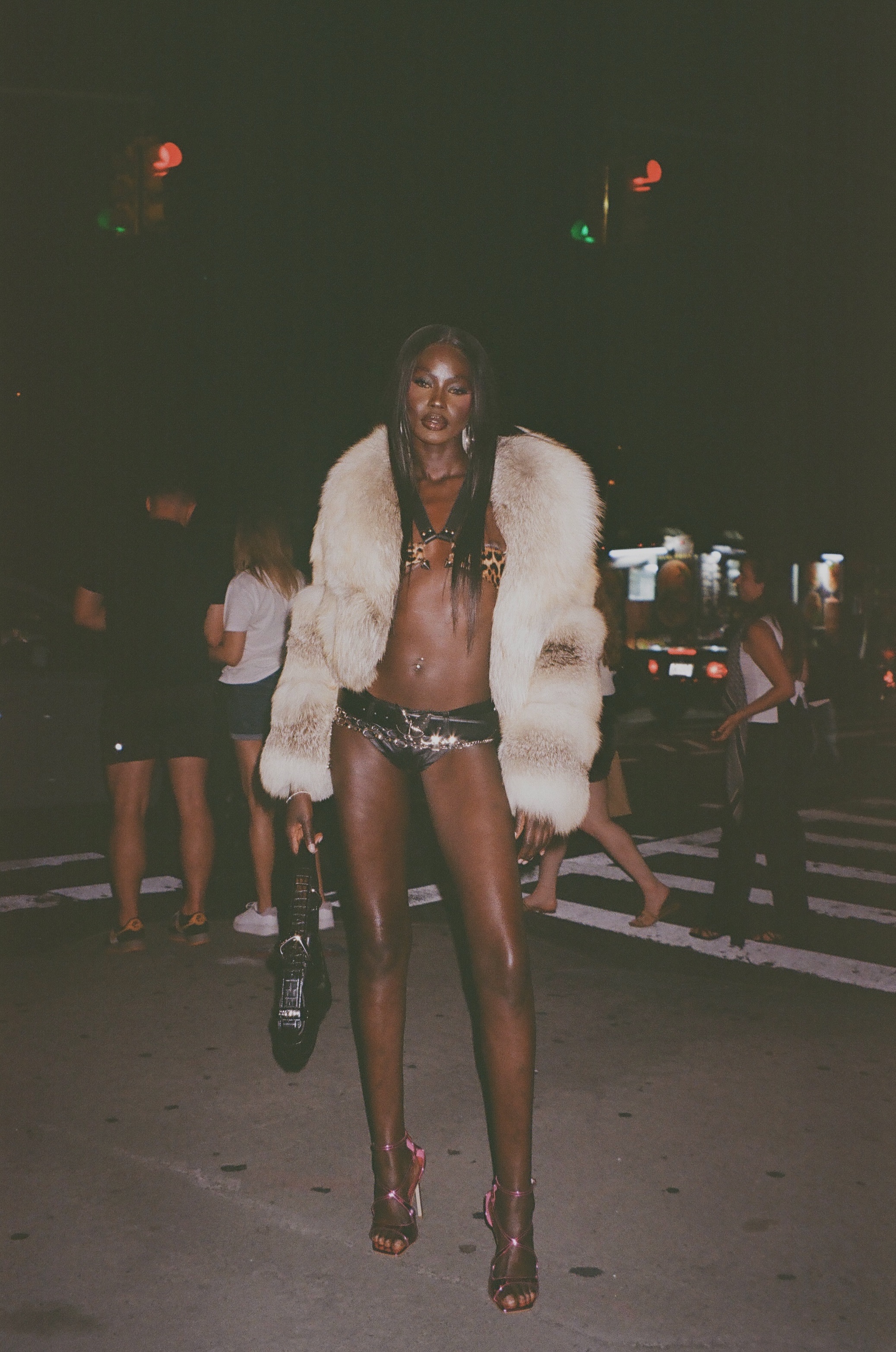

Michele Rizzo, HIGHER xtn. 2024. Photography by Cameron Kelly courtesy of MoMA PS1.

Back in May, I attended Wire Festival, a multiday electronic music event at Knockdown Center that had no shortage of organically united dancefloors. It attracted a crowd of seasoned ravers who were eager to celebrate the start of spring as they danced alongside DJs who played well into the daylight. I left Wire in an afternoon daze to see Michele Rizzo’s HIGHER xtn. at MoMA PS1. My sleepless euphoria only deepened as the performance unfolded, starting with a lone dancer who looked plucked out of the festival.

The dancer, dressed in sneakers, baggy jeans, and a tight tank top, shuffled slowly into the gallery, perfectly in sync with the looping bars of an understated electronic melody. Soon, other dancers, clad in the same staple rave uniform, joined him — each having traveled from Europe for the U.S. museum debut of HIGHER xtn., which premiered at the Stedelijk in Amsterdam in 2018 and quickly became a fixture at kunsthalles and festivals across the continent. As the score’s tempo climbed, the choreography locked into a 16-count sequence, which the dancers executed with precise synchrony. They remained intensely focused, never making eye contact with each other, as they sought release in the endless repetition of synthesized beats. Once the dancers reached their limit, they stopped the sequence and exited the gallery, one by one.

HIGHER xtn. used the focused daylight of the gallery to highlight the meditative release found in the repetitive movements that dominate dark dancefloors. The performance’s restraint brought more consistency and intentionality than Eyal’s all-encompassing club construction in R.O.S.E. Yet both performances offer enticing entry points into club culture for those who may not frequent raves. Rizzo’s ecstatic, hypnotic repetitions reveal how the club can mirror other meditative practices, while Eyal’s interpolation of performance and clubbing helped hesitant audience members blossom by the end. Still, both works overlook one of the most underappreciated aspects of clubbing — its potential for individual expression. HIGHER xtn.’s pristine uniformity especially risks promoting the outdated techno trope that there’s a “right” way to dance to electronic music.

Maybe this shortcoming is, in fact, a benefit. For habitual ravers jaded by one too many sunrise sets, it’s a reminder to return to the club with more intention. If you pause and peer through the darkness, you’ll see hundreds of people moving to the same beat, each with their own subtle variations. This collective choreography is a ready-made spectacle that doesn’t need validation in a theater or museum. And when the music shifts slightly, you can watch the ripple effect sweep through the crowd while feeling the new beat in your body. Maybe this small bit of magic is best left on the dance floor.