New York's Longest Night

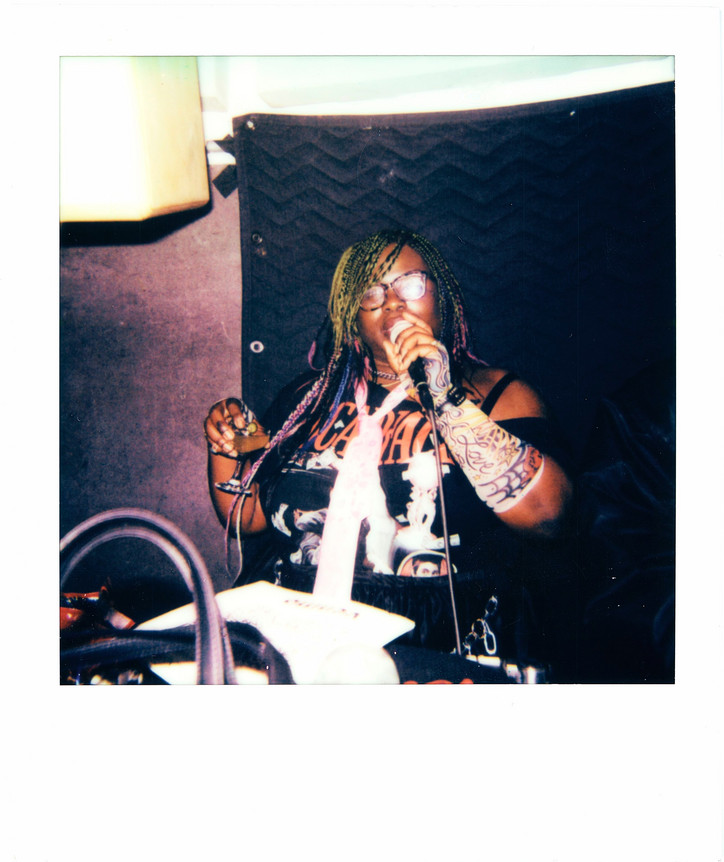

They introduce Kim Rosenfield as “once the hottest teenage poet in LA,” to which she responds, “That was a long fucking time ago.” She prefaces, saying, “I’m also a psychotherapist, so if anyone wants to talk about what they just heard, come find me.” It’s fitting that Kim start the longest night of the year with a poem that she had wrote Halloween. “The veils were thin then. I hope they continue to be.” Her voice is haunting but her words are youthful. It’s clear why she describes Hell and herself as “eternal teenagers.” With her “melancholy on a budget” and “a goodbye so thick you could bite it,” she tells us that “home is just a path beaten over and over again. My favorite line: “It means a lot to me that I can still make myself cum the old fashioned way” — earns hums of admiration from the crowd — I doubt that many of them can say the same.

An academic and a member of Neoliberal Hell, Matthew Donovan brings me all sorts of places — here, Anna Delvey’s roof, etc — he’s one of the smartest people I know. “This poem is for my father,” he starts. No one claps. “If you hate your father I understand, you don’t have to clap.” People cheer. Matthew’s work is sharp — clever, but the kind of cleverness that begets survival. “This wasn't radical. This was an abject desire, scattered in Section 8 project-based housing, a rock thrown at my head, where I learned you could go blind from snorting blood.” Matthew says words we’re not allowed to write in press, remembering how his dad took him to Disneyworld and “lied to everyone that we were disabled so we could cut the lines. He pushed me out of my chair because I wasn’t convincing enough.”

I think this Peter Vack guy is the guy everyone talks about when they mention autofiction. He’s delayed coming to the stage, yelling, “Someone do a bit!” Erin talks about stealing from Rite Aid to make lemonade stands. “I’d be a great capitalist if I were one.” Peter dedicates the poem to his late friend: “He was the best Instagram user ever.” This is the modern age’s most loving epithet. This is what the Greeks wished they carved on pantheons. He’s a real 21st century poet. He makes jokes about looksmaxxing and The Dare, referencing meme formats and reminding me of Tom Robbins. “Your honor, my client was decolonizing Clandos.” This receives laughter and well-intentioned nods of solidarity.

Peter admits he’s from the Upper West Side and says more words I’m not allowed to write. “The real pandemic is reading. The real pandemic is readers.” Matthew Weinberger takes a picture of Peter that reminds me of that kid dressed like a monkey at the Apple store.

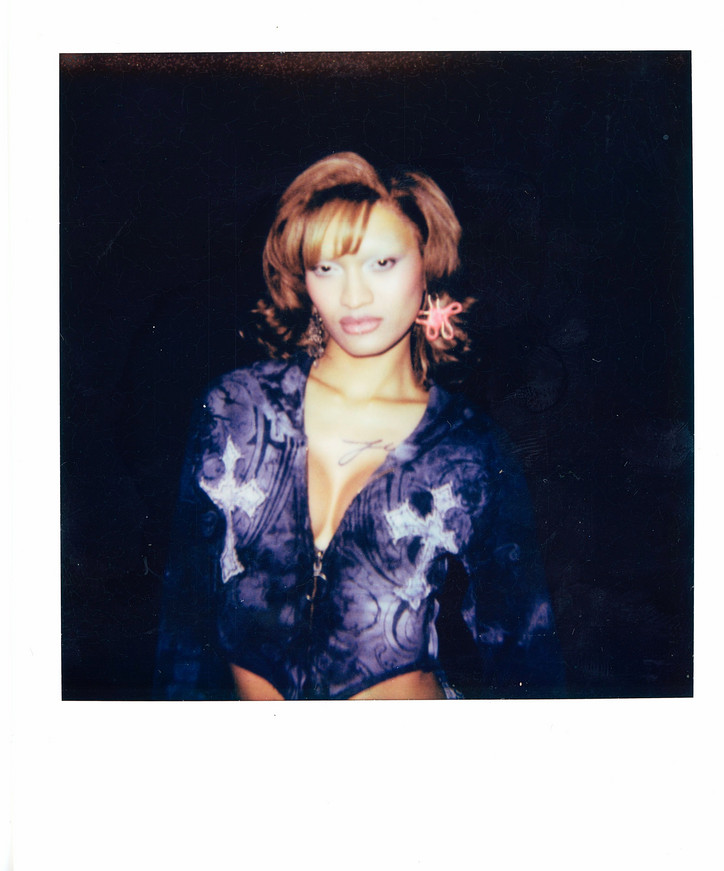

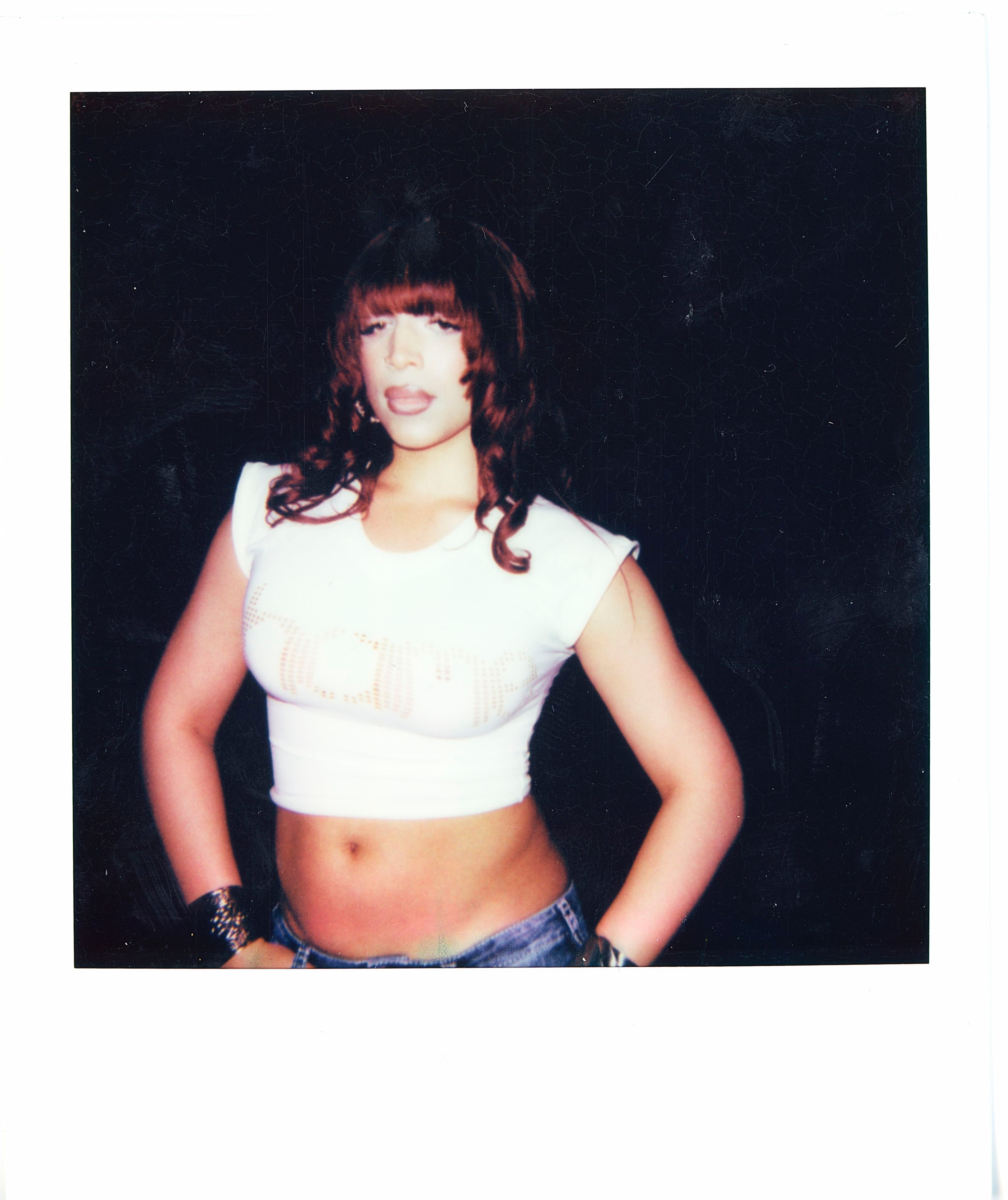

Kitty St. Remy has the coolest name ever. She reads with red boots angled inward and has a poem called “estrogen versus Viagra.” “The only thing they bought me was lube from Walmart, now I remember God is a product of human labor.” We’re floored. She talks about being called a “splendid bitch.” “I’m counting on debauchery and Babylon. I’m pouring wine down your throat at the orgy. All the girls you loved are here, ten years younger with deeper throats.” It’s devastation in a matter-of-fact drawl. Kitty St. Remy writes like her heart hardened out of necessity. This isn’t to say she’s not earnest. “If there’s a point in history where my words could be understood, I’d like to be there.” The tears in the eyes of some of the girls makes me believe she’s there.

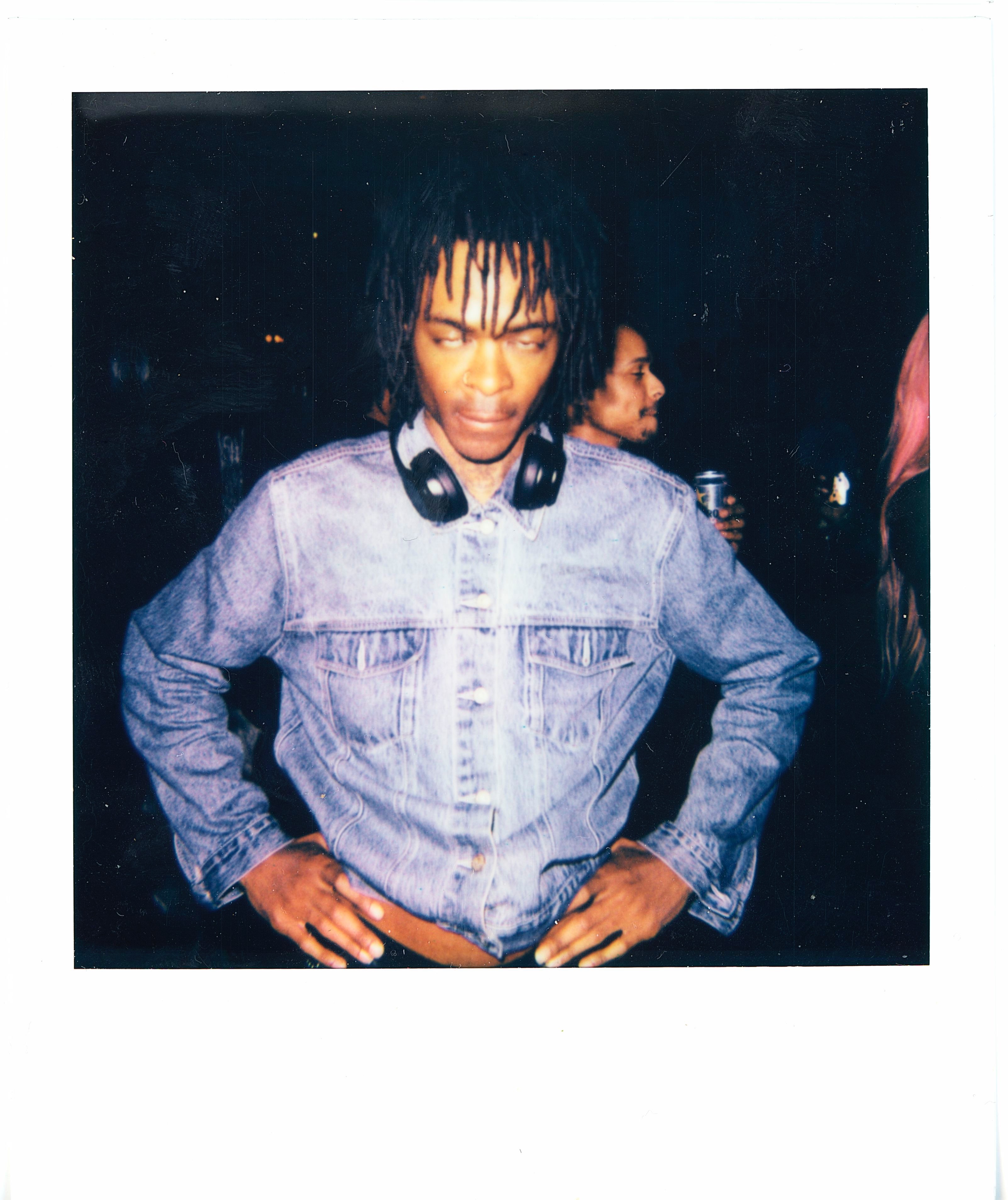

Sean Thor Conroe sets a joint on the piano and apologizes in advance for “bumming us all out.” It's hard to read novel excerpts that aren’t all fluff with a few one-liners. But with Sean, each word means something. He writes about writers who die after meeting, writes about love in an endearingly scientific way — crushing on a girl by admiring her erect posture and symmetrical middle part.

In his story, a man stumbles through a passage that says, “the phallus transforms itself to make possible the conditions of love for women who need daily penetration to feel loved.” It’s a thinly-veiled metaphor on how love forces transformation. It’s an hilarious idea that women need (or receive) daily penetration. We laugh about that. In his story, they pull tarot cards on acid and don’t freak out about pulling the Death card because “we’re dying every day.” There's no laughter about that.

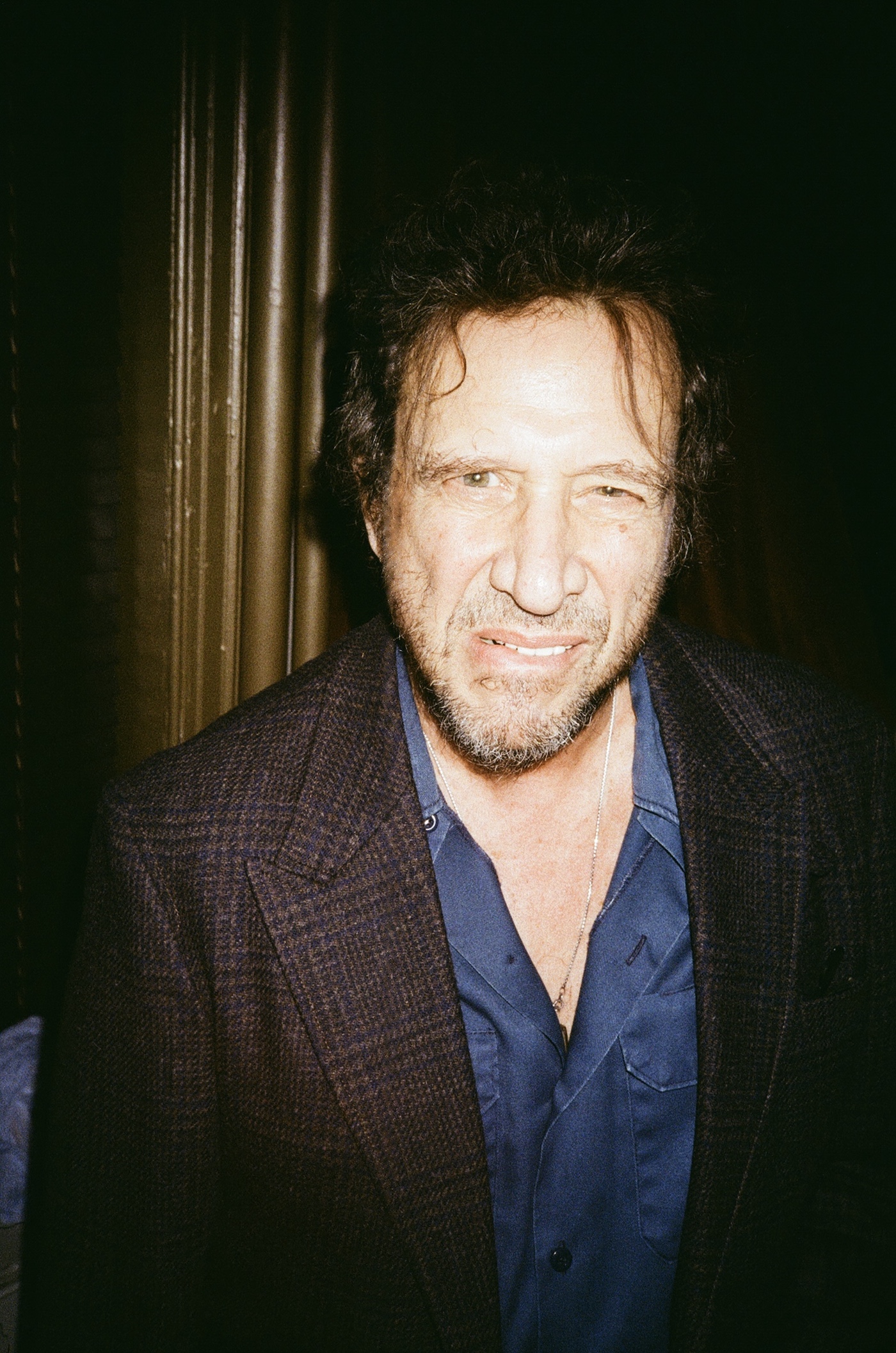

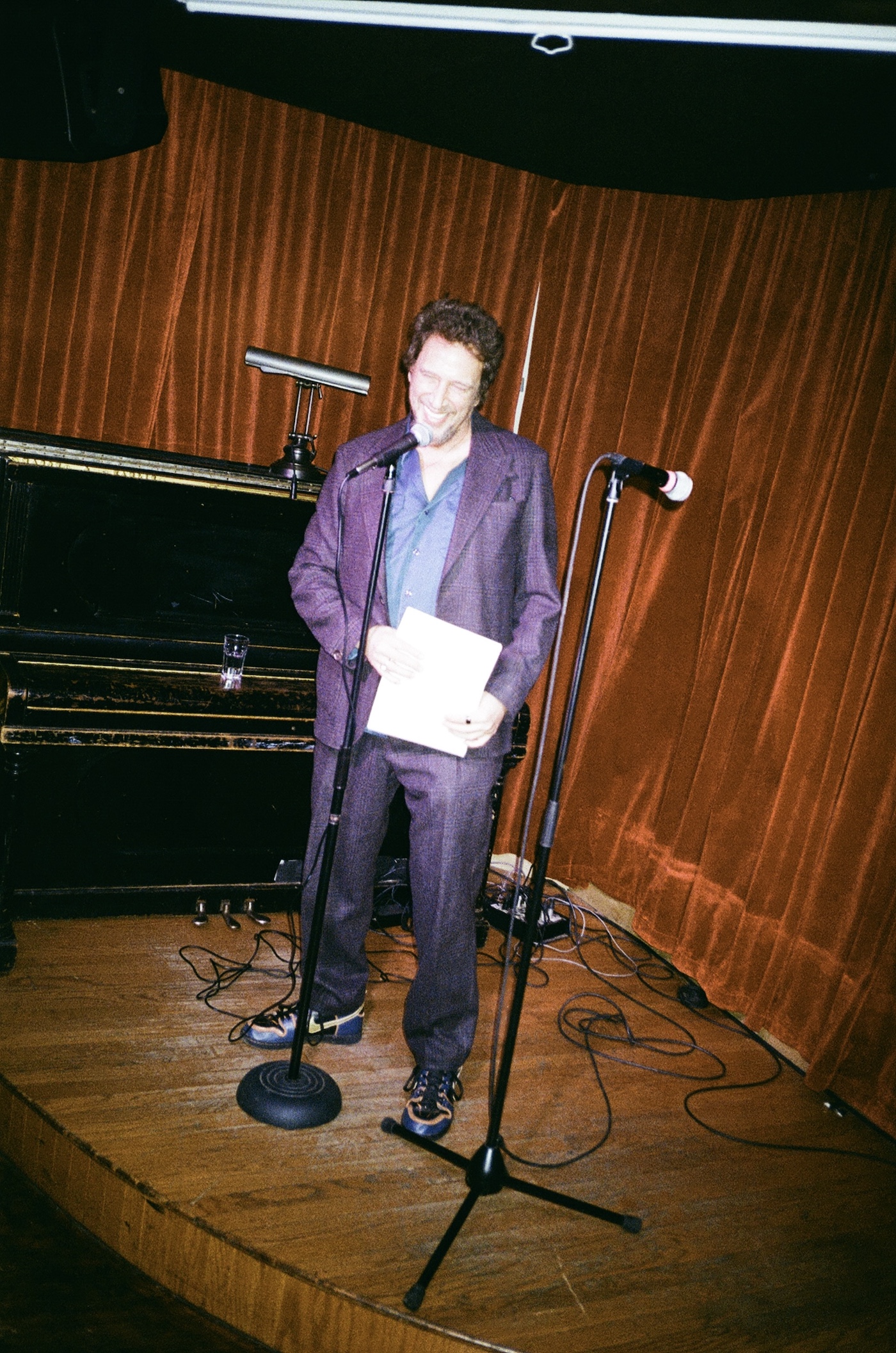

Last night, I was talking about this event, and a friend of mine said that my level of excitement would mirror hers for someone like Cher. I tell her Richard Hell is reading at KGB. She asks who that is. I say he’s “like, the Cher of punk rock.” I don’t know what I meant by that. Who am I write about Richard Hell? He puts his water on the piano and says, “We should celebrate the old year, not the new one, becuase they’re getting progressively worse.” He reads a poem about the start of the millennium, saying “I don’t want 2001 to end, I don’t want 1 or 0 to end. I don’t want to hold onto the past but I want to bring everything with me into the present. This is why they invented jesus.”

His hair hasn’t changed since the 70s. He reads from loose sheets of paper and talks about William Blake. I think about showing him the old commie bookstore I used to work at. He writes about ants and butts, saying, “‘Tub’ spelled backwards is ‘but’ which is almost ‘butt.’ This is how you get from ants to anal sex — with ‘u.’” Everything sounds like a punchline: “When I got out of bed and realized I couldn’t remember my dog’s name, I thought, ‘Dementia for sure.’ And then I remembered I never had a dog.” His poems combine esoteric language atrophy and irreverent humor. “Poets are fools but I don’t give a fuck,” adding suggestively, “... anymore."

“Life is only good if it’s well-written,” he says, and I’m back to my original question: Who am I to write about Richard Hell?

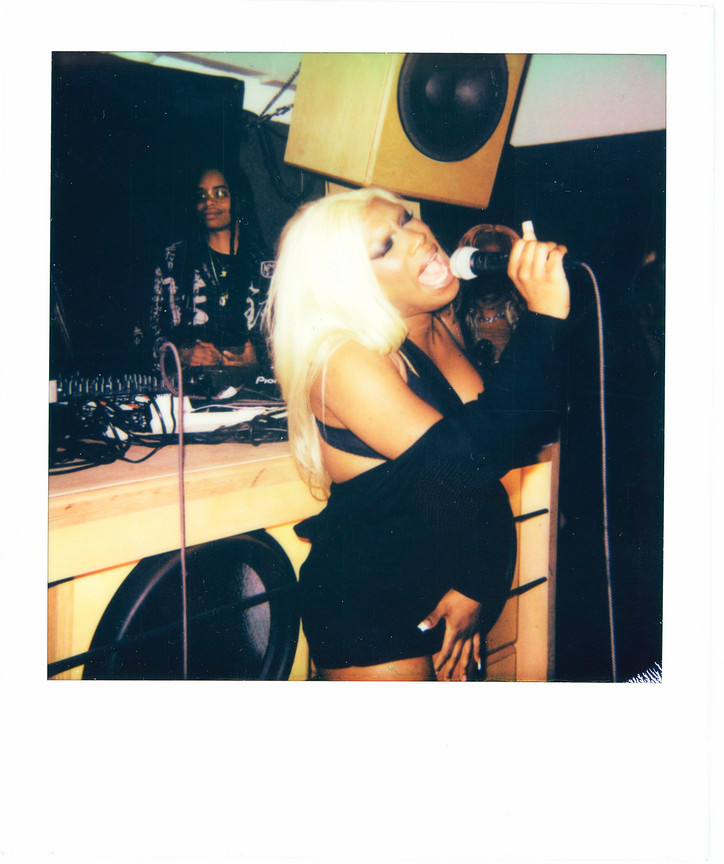

Erin and Britt close with a group carol, a nativity reenactment, and a bag of flour baby Jesus. At the end, they offer up the bag for groceries (Matthew Donovan takes it home). People a proclivity for consuming representations of Jesus — I wonder what baked good the body of Christ will become this time.