Cue the Smoke Machine

So tell me about yourself and your work.

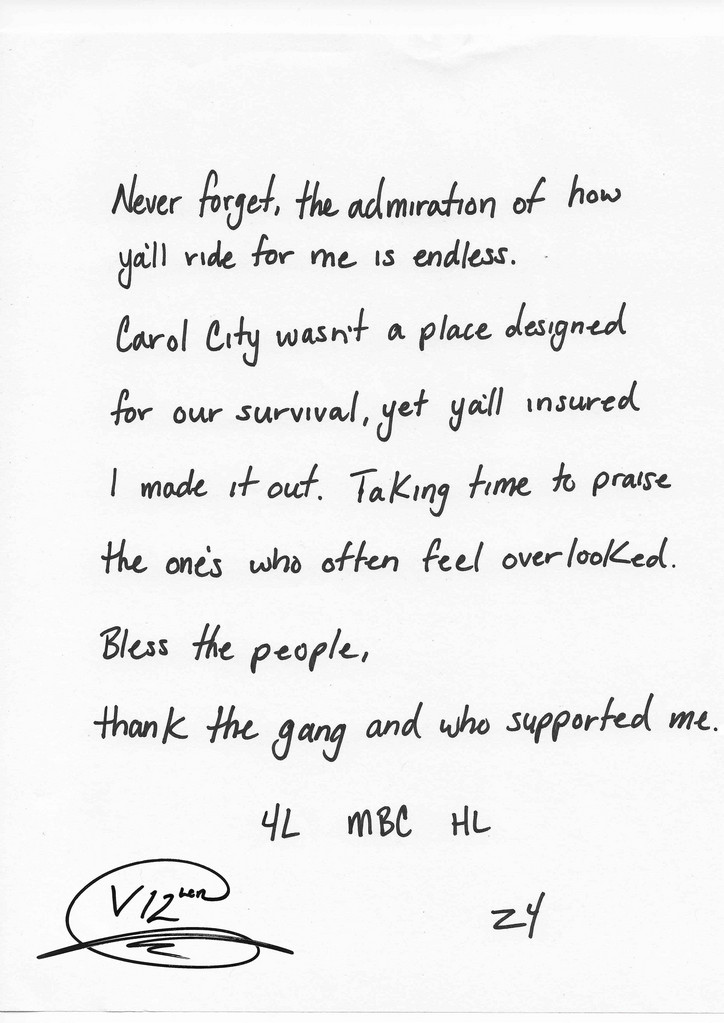

As far as with the music video, the video for “Thank the Gang” started off as a recording, a film recording for a festival that we have here in Miami called III Points. And I just went, and I picked up like a mid-2000s—no, I’m sorry—an early 2000s camcorder out of a pawn shop. I was just trying to shoot some footage with me and my homies for III Points that they could show on the projections. It was a really good show. I played, and then right after me, The Internet came on-stage and played, and then Tyler*.

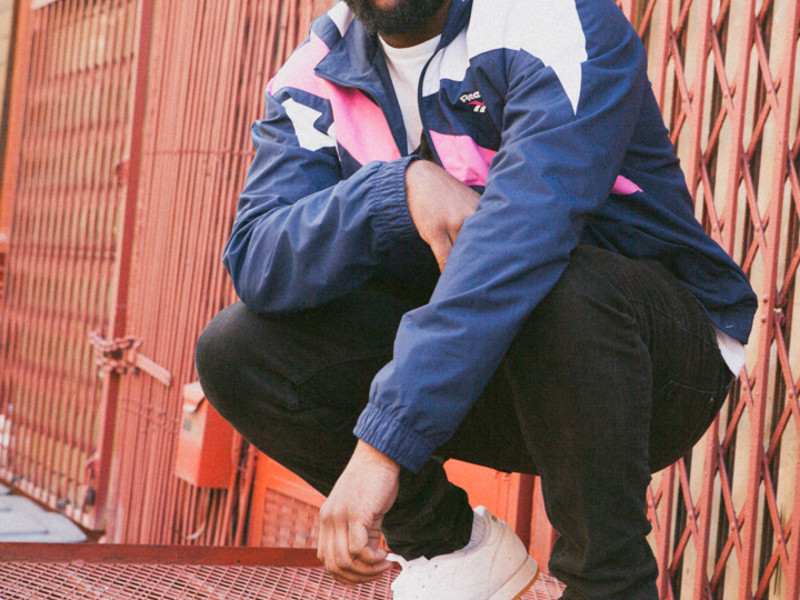

So that’s how it began, as video for projections, and then we just kept shooting. I said I could do a performance in one of these scenes with this camera, and we actually just started shooting it. And I was like, ‘You know what? I think I want to shoot an entire video with this film.’ Because with the entire album itself that I’d been creating, it’s been built around a lot of 90s and 80s R&B aesthetic and also a lot of influences from Miami that didn’t get the light shined upon at its time. Like the DJ Uncle Al, you know? A lot of people know about, like, Uncle Luke when it comes to Miami culture, but they don’t really shine light on Uncle Al, who is the originator. So, a lot of this stuff is inspired by Uncle Al, like the sample that you hear at the beginning? That’s from Uncle Al. It’s more of the aesthetics of who I am, trying to create a balance in keeping R&B traditional, but still showing this essence of what colored culture, or urban culture itself, projects when it comes to R&B and alternative music. Because growing up, like you know, coming where I come from, I listened to a lot of Frankie Beverly and Maze and a lot of Al Green and Marvin Gaye. And those are the records and that is the music that was projected in our neighborhood that growing up—well, me growing up in my household—it’s what we listened to.

Nowadays, the music that is pushed more into the urban market is, you know, the more heavy-hitting hip-hop rap, you know, trap shit, you feel me? Which is cool, I enjoy it, but it’s kind of fucked up when you have an artist like myself that is doing something that is different from what the mass is doing, coming and being projected amongst our culture of the urban culture. So I get looked at, you know, weirdly at first, until you actually hear it, and you feel the soul in it. And you realize that it’s always lived within you, you know? Because you grew up on it. But we just been disconnected from it for some time, because of what urban culture has been projecting today.

Right, so it’s almost like a return to origins or an embrace of the past?

Yeah, embracing the past and embracing unity and loving one another and coming together, you feel me? Enjoying each other’s company, you know, like those backyard functions and those barbecues when you’re with your family. And when you’re with your lady, you know? When you’re out on your date just having a good night, having a good time, and just growing up. Getting past all the hype.

Part of what I liked about it is what you’re saying, it’s a very different theme just in terms of the lyrics, and the attitude of it is quite different and less aggressive than what is generally perceived these days as cool, like hip-hop, which can be almost jarring and intense sometimes. So it’s really connected to Florida as well?

Yeah, it’s definitely heavily connected with Florida, yo. I actually grew up across the street from the guy named DJ Chipman. He was a very known DJ from even way back in the late 90s as well. He had a few records that—well, not a few—he had a record that was featured on Family Guy as well. It’s like a dance record. It’s a dance record called Peanut Butter and Jelly.

Oh my god, wait, he wrote 'Peanut Butter Jelly Time'?

Yeah, that’s DJ Chipman, yeah.

Oh my god, no way. That’s crazy!

Yeah, so I actually grew up amongst these people as a kid versus a lot of these other musicians, you know, from Florida who know these records and grew up on it. I actually, like, grew up under these guys. They knew me as a child, you know? I knew Rick Ross as a child; I knew Flo Rida as a child. Like I was in the studio with Flo Rida and Rick Ross. I even did vocals for Trick Daddy as a child.

Wow.

Yeah. All of them’s from my neighborhood, you know? Like literally, from my neighborhood.

That’s crazy! So how old are you now?

I’m 26 now.

Okay, wow that’s so interesting. It’s always interesting when a specific neighborhood or a specific place sort of produces a lot of talent. How do you think that happens? Or like, how does that come about? Is it just from people bouncing off each other?

Yeah, I think it was because of people bouncing off each other, or it’s probably something in the water. I don’t know. It’s probably something in the water.

Do you feel a certain pressure to participate in more of the current, aggressive style of hip-hop?

I don’t feel pressure to participate or even dabble into it of any sort, because I grew up on it as well, you know? My favorite musicians would be like Al Green and Marvin Gaye. But actually growing up listening to music, if I had to select music to actually play, I mean, I played a lot of R&B. I played like—my favorite artist growing up was 50 Cent, you feel me?

Ugh, I love him.

Yeah, that was my dude.

He was like my conversion to hip-hop. Him and Kanye West.

[Laughs] Yeah, Kanye West, 50 Cent. Goodie Mob, Outkast, Tupac, like those—that’s what I listened to. Like when I do participate in, like, more of that type of style of music, it’s just like being home, you know? I enjoy the art, the rap music. I love it. Like I fucking love it, but we gotta still have a balance in which we have this area we can go to continue progressing in life instead of being in this one way. And that’s—I feel like that’s the piece I play in neighborhoods like my neighborhood. Outside of my neighborhood, that’s the piece I feel like I play to inspire. Those, I understand, are like, ‘Ay! You know, you a songbird, of course. But you don’t have to make this type of music.’ Like you’re doing something different.

But in all reality, this is the music that your parents raised you up on. This is the music that your mom played around the house, your grandmother played around. Rap music’s only been around for—it hasn’t been around that long. It’s been around what? Like 30 years? 30-35 years? So before that, all we had was soul and rock, you know? And R&B. But that’s my whole thing. It’s that you don’t have to feel like you’re being misplaced in trying to keep it traditional, you know?

Would you classify yourself as an R&B singer more than a hip-hop musician or do you dabble in both?

I mean, I dabble in both. But I would definitely always set my music in R&B, because that’s what I’m more—that’s what I’m true to.

You definitely don’t hear a lot of R&B these days. There was a really cool R&B moment a few years ago with Usher and Trey Songz.

I feel like R&B kind of got stale, because it stopped evolving. And now, R&B has begun to evolve again, because it’s pulling those great things that you like from rap and adopting it into R&B. So therefore, it can evolve once again, you know? It can emerge once again. You know, so you had, like, that whole era where you had—They call it “trap R&B.” Me personally, I don’t like it. I don’t like that. I’ll only accept trap R&B from Bryson Tiller, from The Weeknd, PARTYNEXTDOOR, Drake, and 6lack. Other than that, I don’t accept it from no one else. Because I feel like we shouldn’t have to adopt hip-hop so much into a genre and ruin the genre, you feel me?

That was my whole thing with creating my project, figuring out how to create R&B music and make sure when you hear it, you feel like, ‘Yo, this is R&B. But... it got a bounce.’ It makes it feel hardcore, but it’s R&B, you know what I mean? Like that was my whole thing. Trying to figure out how to balance it, in which I can evolve with traditional R&B. Like listening to Isaac Hayes or listening to Usher and making it today, making it modern, you know?

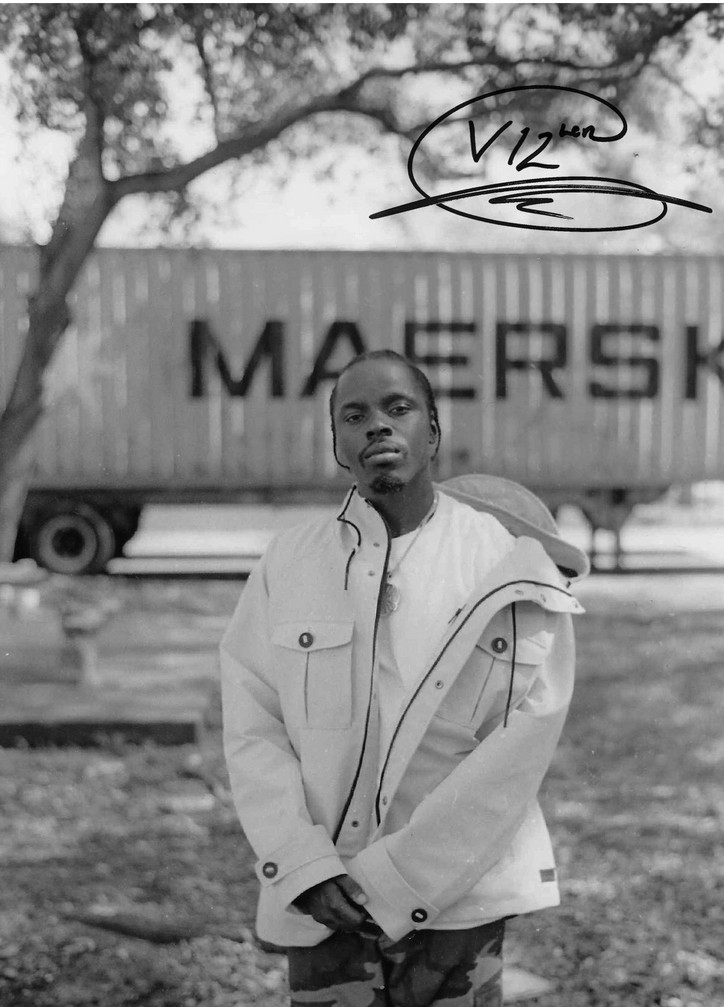

Check out Twelve'Len's new video, 'Thank the Gang' below.