Dayglow Plays M3F

Stay informed on our latest news!

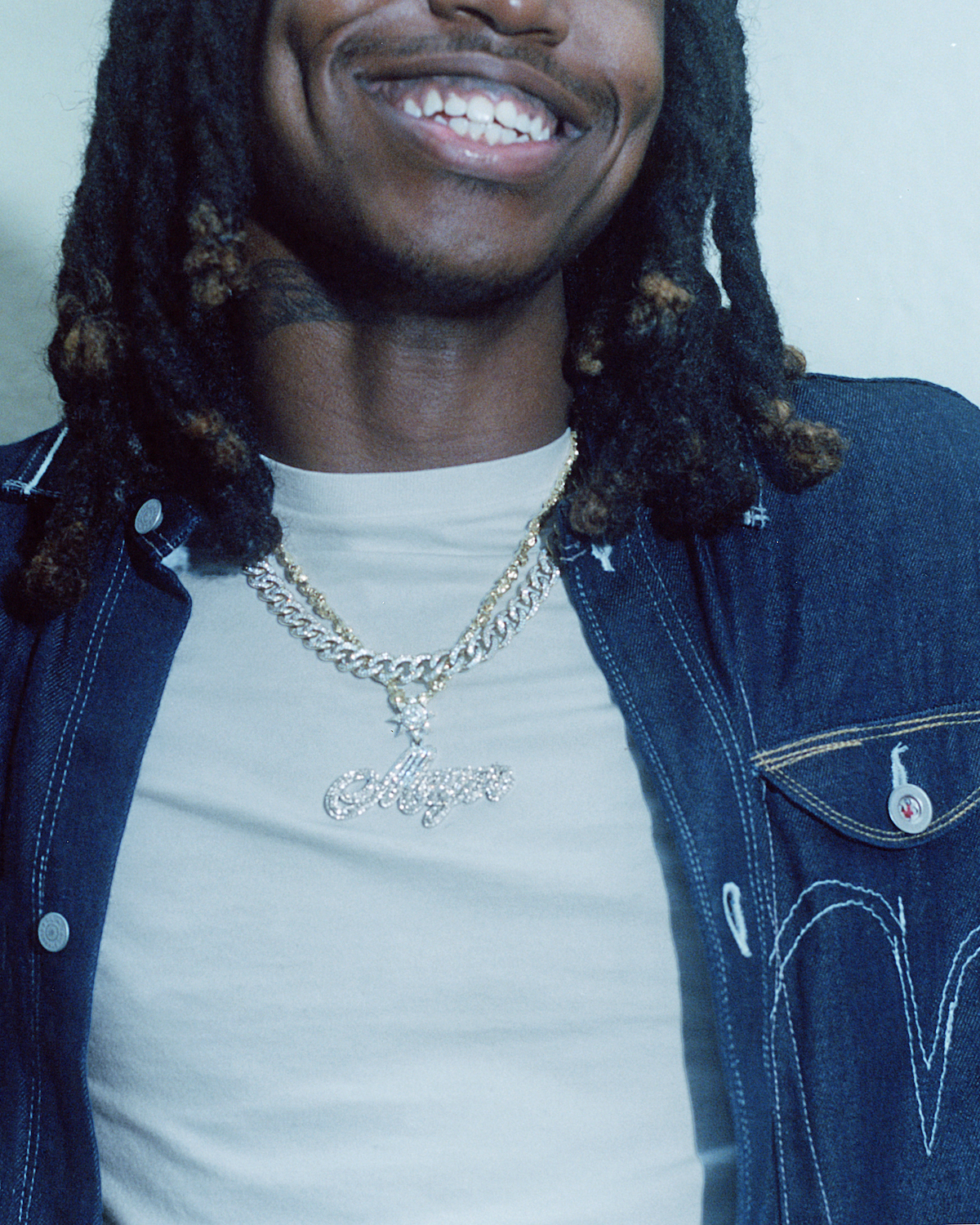

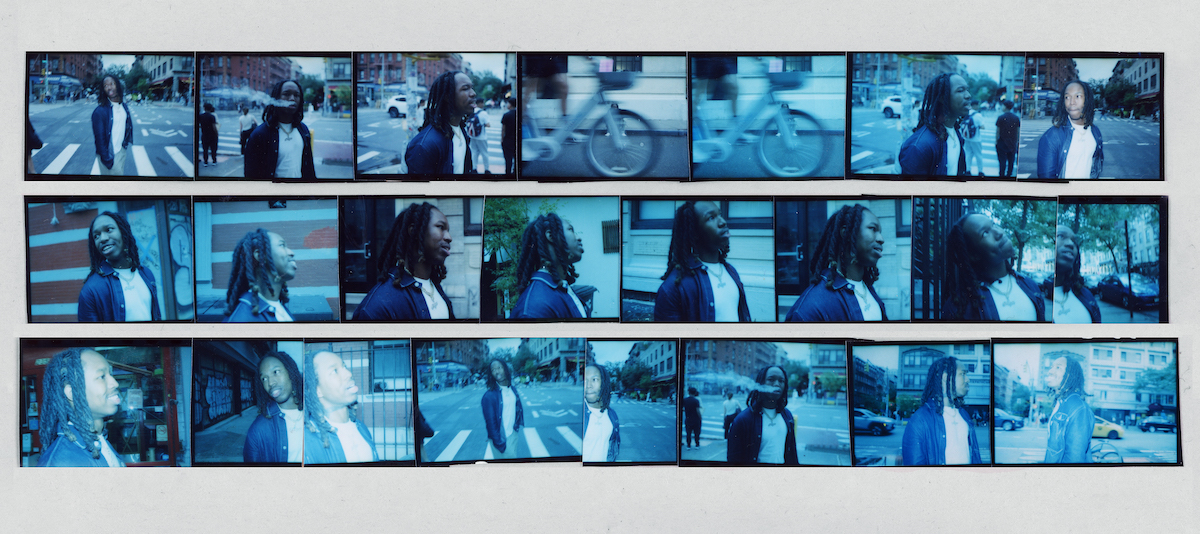

In the time it took the 24-year-old Charlotte rapper to record this album, the third of his career, he struggled with finding the right name for it. On the day of its last recording session, MAVI enjoyed a card game with a girl he often played with. She asked him to sign the card on the top of the deck, so he did. “MAVI is in New York working on his untitled album,” she then wrote on the card. “I'm going to keep these for your shadowbox,” she added after. Ding ding ding.

As MAVI now sits across from me outside of MUD, an earthy cafe in the East Village, his voice cuts through sounds of clinking glass and neighboring dialogues, illuminating a watershed moment for the most methodical piece he’s ever worked on. “When she said that, it was like, ‘That's exactly what I've been making,’” he muses. “I've been putting all of these different failures and triumphs and experiences into this fuckin’ 3D frame for people to play with.”

MAVI is patient and measured with his words despite Manhattan’s incessant racket, never really raising his voice until the conversation opens up to shared laughs and colloquialisms. Even then he remains even-keeled. When he's not contextualizing his music, he paints pictures of his future away from it: One day he’ll jumpstart his nonprofit and give out free laptops to kids in Charlotte. One day he’ll teach biology where he once attended high school. One day he’ll be revered for much more than the words he’s spoken into a mic (even though he plans to keep rapping 'til he's dead). Among other things, MAVI opens up to office about his appetite for literature, the friendships he's built through music, and the process behind shadowbox.

Olivier Lafontant— How do you feel like this new album is a continuation of you processing the interpersonal struggles you’ve gone through?

MAVI— I think for this one, I was making the songs because of a lot of chaos happening in my life at one time. And I was making the songs to document what was happening so I could try to map out the lesson or the message of all these events in my life. And so that became the backbone of the album, the path that was drawn through [me] being pulled in so many different directions.

Something that’s a common theme in your work, especially this time around, is how meticulous and artful your rollouts are. I've seen the art pieces that you’ve been posting on your Instagram, for example. How do you feel like the visual components serve as companions to the music?

I wanted to craft a language — like an aesthetic language. So things being carefully arranged, things being voyeuristic throughout the album, me speaking from a removed perspective about myself; these are all things that I wanted to visually express through shots in the music videos or things like the tracklist or the tour poster. And then also because I'm talking about things that are cyclical — addiction, love and loss, transformation — I wanted to display it in a systematic way. And then also being really tactile: The album cover is a platinum/palladium print and it was mastered on tape. Adding a degree of physicality to everything, [like] having an incense that comes with the vinyl [has been important]. These songs are all things that happened to me those days that I made them, and then over time they’ve become like a photo album.

What do you hope to accomplish with this record?

I want people to make this record their own, feel humanized through it, and humanize me through it. And I want people to stand in front of the painting, even if they don't read the placard, even if they don't buy the painting. Just stand in front of it and feel moved. Because I think moving people is the one thing nobody in music marketing or music strategy really thinks about. It's like, how do we take this music, whatever the music is, and then get people to move as a result of it?

Could you describe a transformative experience that's happened since the release of your last album that's helped inform this one?

Oh, man. I’ve had a lot of transformative events the last week. I've bought a house since the last album. I broke up with the subject of the last album, got with somebody else, and broke up with them. One transformative event has probably been going to Paris, going to their modern art museum, and really understanding [that] I was overthinking art. Me thinking I was not informed enough to understand art prevented my access to being moved and building relationships with artists and art, on the visual side. So I removed that barrier, and that's when I really started to take in design and digital art as something I can understand, play with, and leverage.

Was working on this album the first time you had that much of an influence on the artistic side of things?

Definitely. A hundred percent.

Something that really sticks out to me is when an artist like you is so poignant about the vulnerable experiences a normal person may be ashamed to display on a pulpit. How do you accept that? Does that weigh on you while you’re performing?

When I first started rapping I didn’t want my mom to know I was rapping. And not because rapping is something she would not want me to do, but because of how I was rapping about my own life. And that there were things that I felt empowered by sharing with millions of strangers that I was afraid to share with my mom in that same naked way. So I definitely have run-ins with my own vulnerability in ways that are not just a super warm hug all the time. But I think it's worth it for me because it helps me understand myself. I can rap something that I can't intellectualize and then draw meaning from the rap song. So it's therapeutic, cathartic, whatever. You know?

I definitely feel like because you take that role in your music, the listeners take in what you give out and it helps them contextualize what they go through. Do you feel an obligation to do that, or is it just a natural outcome?

I don't think I feel an obligation to it because that would make me eventually grow to resent doing it and resent the listener [as well]. And I don't think it's something that's necessarily natural to do either, because it's more traditional in rap music to write about stuff that makes you feel cool. But what I think it is is a kindness on my part, like a loving act. That's how I think about it. I need my listeners. Even if it's one of them or two of them, I need them. And because I need them, I will allow them to use me and my story to better love themselves. I think I can go to heaven off that.

Speaking from personal experience, Let the Sun Talk was an album that I played a lot during quarantine. I feel like having that level of companionship, even if it’s through somebody you don’t know, is a crutch.

Right! We’re friends! And that's the thing about Let the Sun Talk that makes it special, even beyond anything in the music, is the context. So just being there for people when it’s relevant is also a part of the mandate for me to [do this], you know? To be there at the right time in the right way.

On shadowbox, you only have one feature on the record. How intentional is it for you to give yourself as much space as you do when it comes to tracklisting and putting out your own work?

I’ve never had a rap feature in my entire career. I kinda don’t know how to make songs with — well, I know how to make songs for people. You can give me the space and I can give you something really great.

Even “EL TORO,” [Earl Sweatshirt and I] made that separately. Like Ovrkast sent us both the beat and we both sent in a verse on the same night. And [Earl] was like, “Yeah, we're doing this.” I don't really know how to rap with other people that well. One thing I want to really do, I wanna do a “friends tape” 'cause I have so many rap friends, and we have so many songs. Because even when we think about [James] Baldwin or just art in general, the community that art established is almost cooler than the art itself. Like there's this photo, I think it's like Basquiat, Grace Jones, [Keith Haring], and like Fela [Kuti] or some shit. That shit is hard. Just that everybody's art is in communication with each other's art is one of the most rewarding parts of learning art history. So I’m definitely trying to get better at that. I think there’s one person who’s ever outrapped me on a song, and that’s MESSIAH! He’s my final boss. But other than that I don’t think it’s happened.

Not even Earl?

What you think?

I do love your verse on “EL TORO” so I mean…

Okay, thank you. But also I don’t think he would ever try to kill me [on a track] though. Me and him it’s like… You know how Darth Vader at the end of Star Wars with Luke, he kind of let himself die, forreal? [Laughs] On some torch-passing shit? The nigga be on some torch-passing shit. But I really do want him to try to beat me. With him specifically, the song where he tries to beat me up and I try to beat him up back, that would be the Earl Sweatshirt/MAVI song to come out on my shit.

What does the context have to be for y'all to get to that point?

I don’t know bro! I don’t think our relationship lends itself to that. And that's part of the thing too, like, think about it like this: Do you know me and MIKE have rapped together one time? It was the first day we ever met each other, we was at Sage [Elsesser]’s house. Me and MIKE never even came close to making a song after that. But it’s ‘cause I really love these niggas. I go out to eat with them, we do other things. We ain’t even establish our relationship in the studio.

Isn't it strange that the common thread is the music though? Do y'all ever talk about that?

[Earl] kinda impressed upon us the importance of us being leaders. We building individual castles in this kingdom. Sometimes we be having a lot of shit going on. Like me and MIKE just did our first show ever in London. That shit was cracking. I’m kinda saving [the collaborations] for myself now. It’ll be historical. It’s like if DOOM had a Madlib beat on Operation Doomsday, maybe Madvillainy wouldn’t have hit so hard.

You’ve mentioned before how it’s really important for you as a rapper to keep reading books. What are your favorite things to pick apart from the literature that you read and apply to the music that you write?

I really like descriptiveness and detail. I was reading Sun Ra’s biography a while ago and it had a whole paragraph about this jazz nigga named Fletcher Henderson, whose music I don’t particularly like, but reading about him in the way they wrote it had me so intrigued. I want to know exactly what these songs that niggas is referencing sound like. That enriches my reading experience. It's like Harry Potter: they had the fuckin’ butterbeer shit. I had to have that shit.

On God, I wanted that shit so bad!

I had it! It’s fire! [Laughs] That feels so good! I love things that bring me into the world of the book.

There's a level of satisfaction that I get from reading a description of something that I didn't have words for prior to reading that.

Right! That’s all I wanna do as a songwriter.

Lastly, you speak a lot about the importance of your proximity to blackness, both physically and in terms of your family lineage. Can you go into detail about your attachment to your ancestry and how that informs how you carry yourself?

One thing about this album is it's rather churchy. “the sky is quiet,” “drunk prayer,” “open waters” . . . This idea of wanting to be cleansed in the water and the blood to be made new. I use the religiosity [from within] the tradition in my family to tell that story. I ain't pay my fuckin’ [Ancestry.com] subscription, but I've been making [family] trees, and I got up to like 1855, pre-slavery. My family, they're from South Carolina which is a huge slave port, but also damn near the closest thing we got to where black people sit still forever. When I was at the show in London, there was these pretty ass Ethiopian girls. And they came up to me and one of them was like, “Aw, your show was so good! Where are you from?” I'm like, “Yeah, I'm from Charlotte, but my family from South Carolina.” And she was like, “No, where are you really from? Like where in Africa?” I'm like, “I don't know.” You know what she told me?

What?

She said, “You should really try to figure that out.” [Laughs]

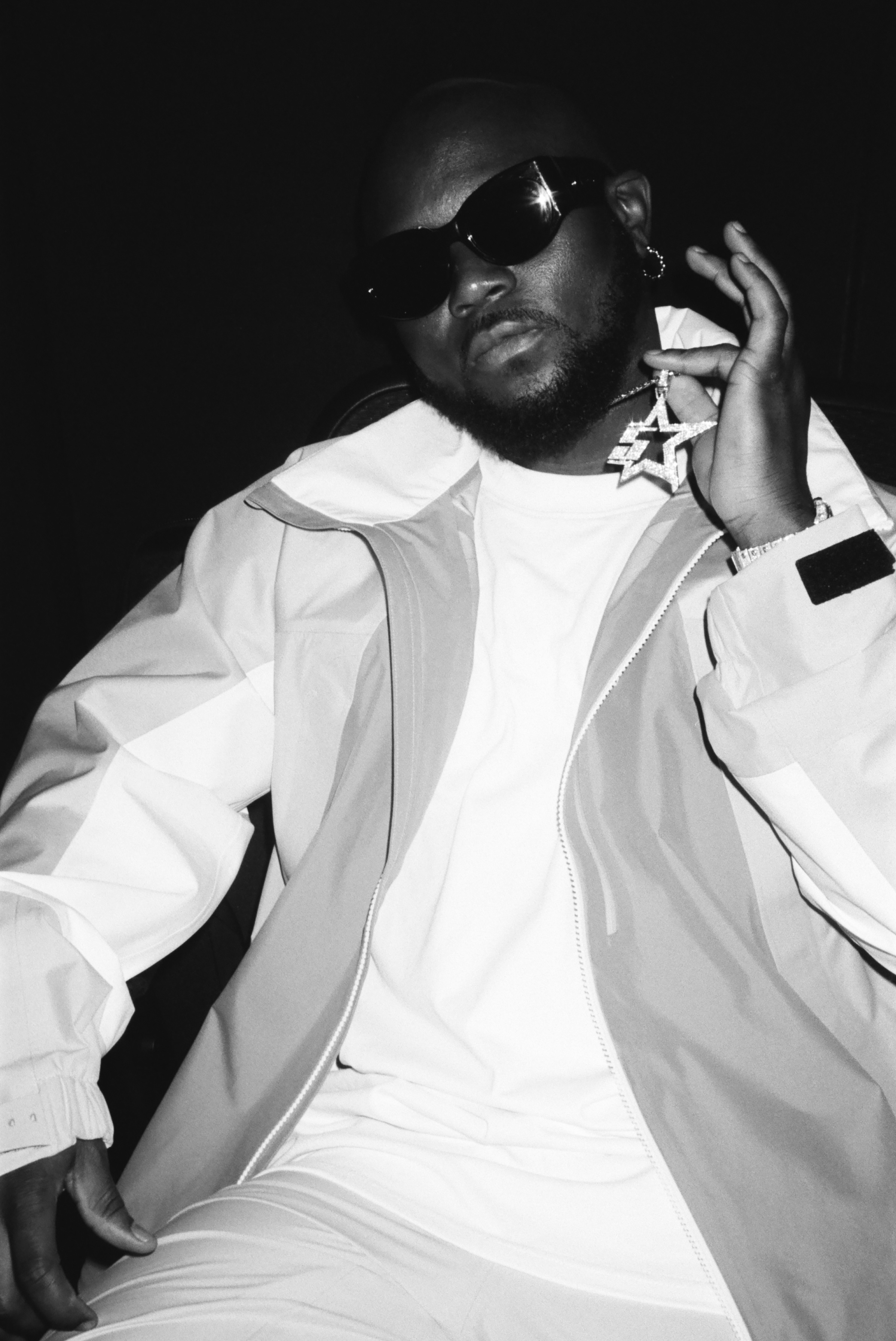

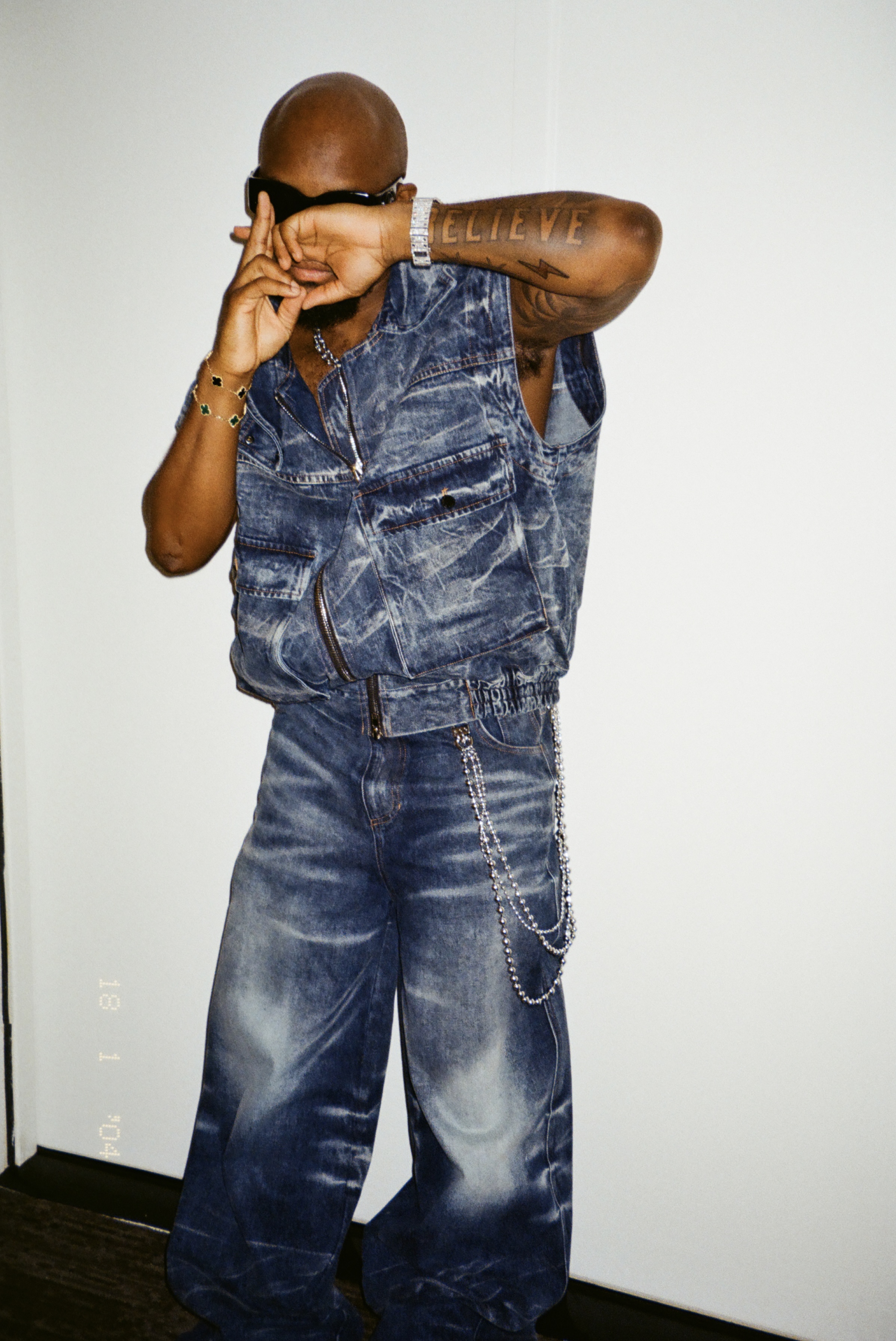

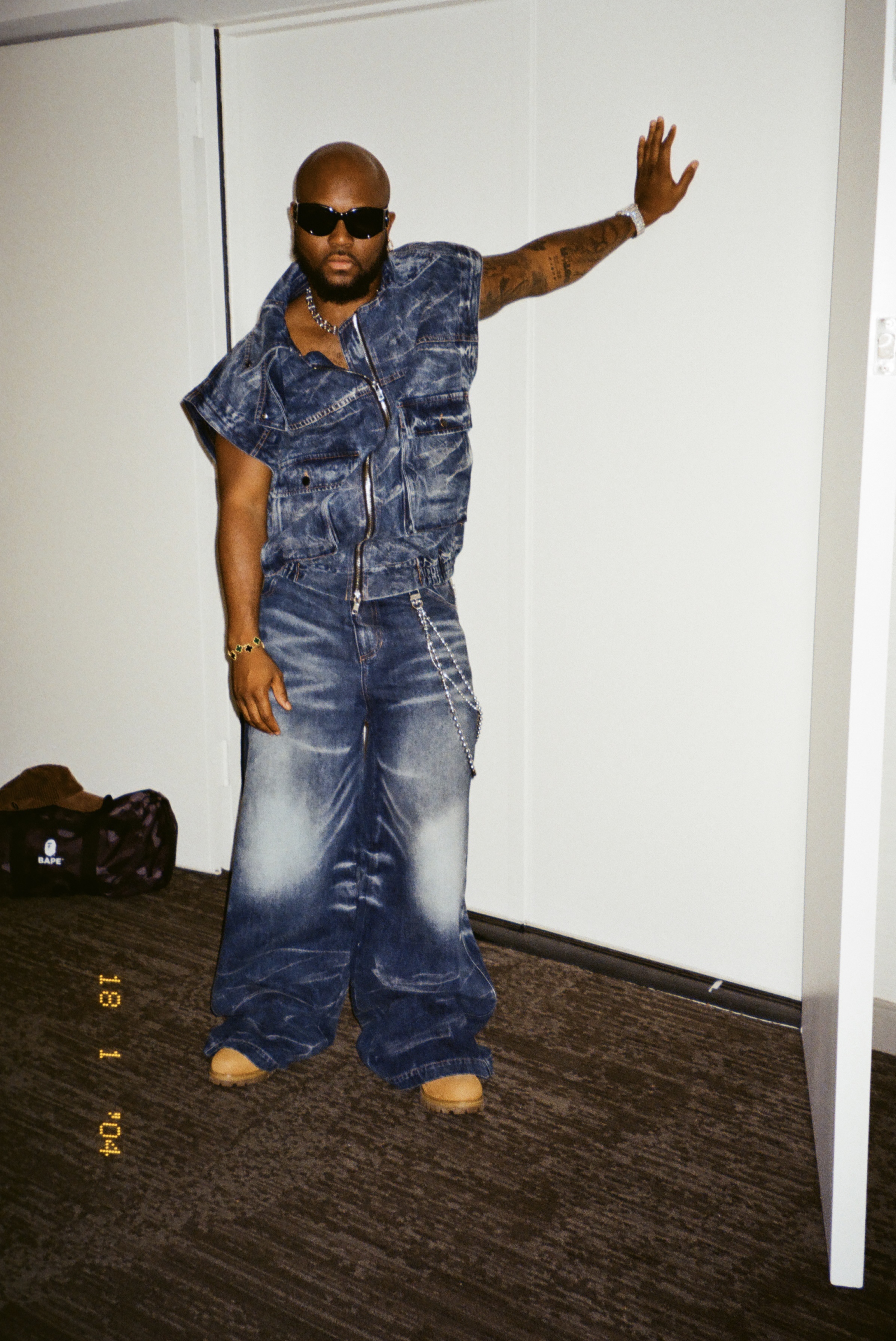

But it was during his university years that everything truly fell into place. Releasing his music on SoundCloud in 2017, King Promise quickly built a following, and soon his buzz went from local whispers to nationwide chatter. King Promise sees Afrobeats as a movement that’s already crossing borders and breaking barriers. Now, with his music continuing to ascend, King Promise has his sights set on global domination — not just for himself but for the entire genre. His recent album, “True To Self” is a reflection of this vision and bringing people together through music.

As KP prepares to take off on his worldwide tour, office caught up with him during his New York dates.

So, how has your time in New York been?

Good, good. I like the city. I do come back often.

I heard one of the shows got rained out.

Yeah, man. The first one, Summer Stage Headlines. But hopefully we can come back and make it happen.

But all the rest went well?

Yeah, everything else was good. We’re off to LA tomorrow.

Can you tell me about your upbringing in Ghana and how you got started in music?

Yeah, I was born and bred in a Accra, Ghana. I grew up in a very average family, the only guy. I blew up in my last year of university. I have a BSc in Business Administration, my Major was Marketing. I had the hobby, which was making music. I had the passion for it as well, but eventually the passion kept growing. I kept pushing. I didn't know what I was going to do after school, I’d probably look for a job or whatever. And yeah, after I blew up I was like, ‘you know what?’ This is exactly what I want to do with my life. And the rest has been history.

Was it something that was in your family? Were you around music when you grew up?

Yeah, my dad played a lot of music at home. So my dad had a boutique when I was growing up and usually when I closed from school I’d go watch over it. And he had the speakers, huge speakers that played loud music to the streets and he had his CDs and whatnot and I got to handle that a lot as well. So basically his taste and music influenced mine before I became a mind of my own and started choosing what I really liked.

What sort of boutique was it?

Clothes, fashion. Both men’s and women's.

That's cool. Did that affect your style now?

A hundred percent. From when I was a child, my parents dressed us up. My mom and my dad met when they were buying clothes in an open street market in Ghana. And when we were kids to a very older age, they literally dressed us up all the time. It was like a thing where looking good was part of how we grew up.

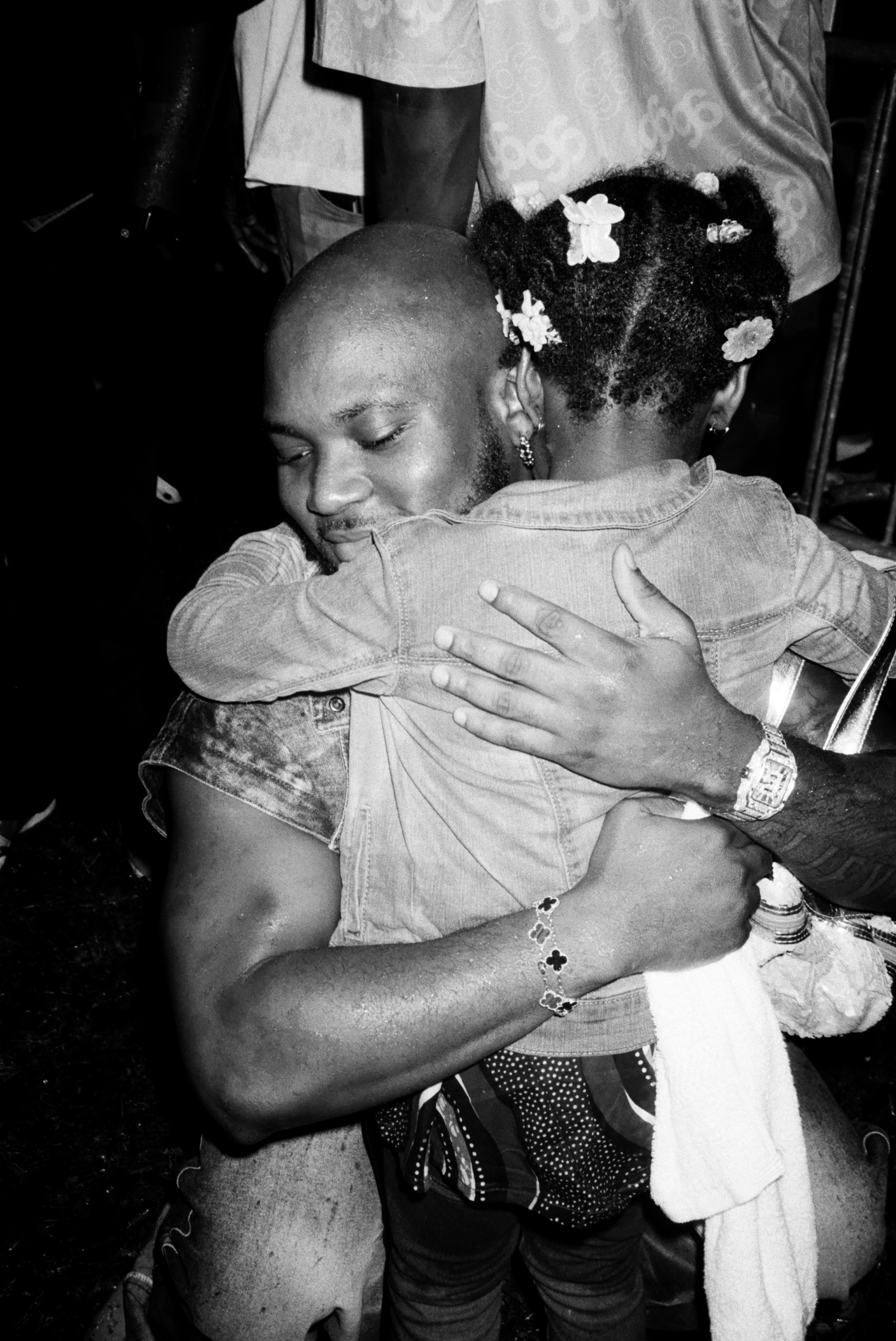

Does performing in the US have a different vibe to when you're performing in Africa or other parts of the world? Do you see a difference?

Every city, or every country, continent or whatsoever have their own type of audience, fans. It's just different. Performing in Europe is different from performing in America, definitely. Performing in Africa is different. But they all have something distinct about it where it's love. It's just shown differently.

It feels like Afrobeats is growing all around the world. Why do you think that growth is happening?

A hundred percent. The music is good. When you hear African music, you just want to get up and dance. You just want to move. It’s feel-good music. Do you know what I mean? It's not really about violence or guns, none of that stuff. Its usually just about having a good time and speaking about life and what's going on with our community. So it's always feel-good, happy music. And obviously it makes you want to move your body and it's just a matter of time until Afrobeats becomes the biggest genre in the world. And I could attest to the fact that it will be, because as you can see, it's taken over.

Do you think there's a reason that it's now getting a spotlight in mainstream or Western culture?

The music itself is really good, it just needed a platform, people to hear it. It's not a new genre. It's been around for a while, but it took people before us to pave the way for us to get here. And we even have to do much more for the next generation that will come after us. And for me it's beautiful, as an ambassador of my people to the world through my music to do what I do and I’m just super proud of the fact that it's ours. Do you know what I mean? The world loves it and it is a beautiful journey.

How would you describe your own personal sound?

Melodic. True. And jiggy.

How's the response been to “True To Self”?

Amazing, man. It's been a month since it dropped and some change and it's just good to see that people really love it and fuck with it. Obviously there's a few hits, couple hits, maybe a lot of hits on there. So it's just a great feeling that people appreciate the sound because I really made it from a special place where it's music that depicts a part of my life or my journey, my career and how I truly feel. Because it's not just words, it's more special than that.

What do you feel is next for you? What's the next chapter?

We always keep pushing. The plan is always to do better than we always do. Always next level stuff. Obviously I've started a tour, so I'm about to do Asia, about to do Europe, the UK, Africa, and also going to announce the American tour dates as well. So there's so many things coming up. We’re working on our deluxe right now as well. So it's just a lot of stuff and I really can't wait to share. But also I'm very excited to be in front of the fans and perform to my people and we do it together. That's also a very special moment that inspires me a lot.

From social media management and event promotion to web design and curation and so much more, it takes a village to make Level III happen. In addition to co-founders Dennis Franklin and Antony “Ant” Ramirez, the work of the collective is made possible by Will O’Brien and Faith Cheung, as well as Chim Tasie-Amadi and Lilah Beldner (not pictured above).

office joined Level III during one of their radio sets for this shoot, featuring DJs Suavez, Syd, Shekdash, and friends of the collective. Later on, we caught up with Dennis and Ant and discussed the origins of Level III and their hopes for the collective. Read our conversation below.

Brook Aster— How did the two of you meet? What were the early days of Level III like?

Dennis Franklin— We met sophomore year of college. I was in an apartment on 125th Street and Broadway, [living with my friends] Lani and Will. Ant would come over all the time because he knew Lani, and just hang out, but I didn't really interact with him too much because I had three jobs at the time. I don't know if we ever formally had a conversation the whole of sophomore year.

Towards the end of sophomore year and moving into the summer, we had this group chat of all these Black sophomores who were working in finance that summer. We all were working incredibly hard jobs during the week and we wanted to have parties on the weekends. And Ant had the craziest apartment.

Antony Ramirez— Looking back now, it seems unreal. I lived on West 107th Street. The apartment was huge; it had four rooms, we had a big living room and we also had an outside patio. We would clear the living room area, with the couches pushed to the walls, and you could still sit on the couch, but there would be a lot of dancing space. Then we would set up outside and we would invite everybody. That's when Dennis started DJing.

DF— It was incredibly convenient because in my freshman year, I had been rushing this frat on campus and it just didn't materialize. We had all these speakers in the frat house that then got dissolved. We were told to get all this stuff out of the house by June or something. I was like, well, these would be perfect speakers to bring to this kid's apartment, who I'd only met like three times. We went to Guitar Center and bought this $500 amp and went over to his house and put them up on stands in his living room, and I put the DJ booth in the corner. For the first party, we texted this group chat like, tell everybody you know to tell everybody you know.

Did you have any criteria for who could come? Especially given that these parties were at Ant's home.

DF— We had no restrictions on who came. We really didn't care, we just wanted to build the party. It was a full BYOB situation. We probably packed it with 250 people in this basement, but then outside, there was a terrace that had these stadium steps on it. You could have like four levels of people just chatting and when you walked out, it looked like a whole function.

AR— We even had a mini trampoline there. But there was no AC, so we had this massive fan in the corner that would just go left to right, and everybody's sweating, sweating, sweating.

DF— People would just come in waves because they would show up whenever they found out about it. So it started around 10, and I'd start djing and we'd probably end every time around 4a.m. or 5a.m. There'd be waves of the standard friends that we know and then there's this whole community of Nigerians who go from Nigeria to London to New York, and they'd all show up too. Sometimes people leave, and show up again at 2 a.m.

AR— We never had any problems with people that came to these parties. There were never any safety issues. Everybody felt welcome and we were never trying to play the cool guy or be like, you can't come into my party. We welcomed everybody, like please invite your friends! I feel like we had a good grasp of who we were inviting generally. Even the strangers we knew were decently good people. And it was amazing.

We were very consistent with throwing them. Sometimes it would be like 8 p.m. and we'd say, “yo, I think we should do a party again.”

DF— It would always be decided maybe an hour or two before it happened. Then people would come from the Lower East Side all the way up to 107th to go to this party at like 8 or 9 p.m.

AR— I would literally go and buy alcohol with my own money, and I was just happy that everybody was having a good time. We’d throw a party and immediately think about the next one. Then we started thinking about throwing more official events, and we did our first big event in Manhattan.

DF— It was an open bar, and we probably sold 350 tickets to that. And it was l the first club that I had ever played at too. It was an interesting experience because for so many of those people, they had only been to parties that summer in this basement that had no structure to it.

We were like, damn, people really will show out for this! The overall community just wanted to be with each other. You always see the familiar faces, the familiar friend groups and whatnot throughout each event.

I'd be remiss to not mention Jaden as well, who was one of Ant’s roommates at the time who unfortunately passed away the fall after that. He was battling heart cancer, and had heart surgeries every single year pretty much since he was born. He was one of the really core people of that group who would get a lot of people to come to the parties.

About 14 of us went to his funeral in Cincinnati after he passed away in September, and that was a big moment for our larger group recognizing how much of a friendship we had all built. That summer had really changed so many people's lives, and gave a lot of us a sense of connection to the city.

DF— We went abroad to London in senior fall, and that was a pretty impactful experience for me. We were going to all these parties that were just so incredibly well run, but also just musically very vast; people exploring genres that we either had never heard of or had been scared to play for other people in the US. London is just so much of a more open space.

I remember I played at a venue called Dalston Den. The ceiling was probably 8 feet high. I was playing all jungle drum and bass, going in on what my knowledge was of that. People came up to the decks and just started banging on the decks — in a good way, taking their shirts off and just going crazy. There was just a different energy there that we really wanted to be able to embrace in like in New York.

We came back full force that spring. We did our first event called Saturday Sessions, and then another one called Open The Garage. That one was really great — it was first one where we were moving away from an audience of mostly college kids. It was just people who found us and thought the event was cool. From there it was like a pretty easy way to start moving ourselves into more exploratory genres, exploratory DJs.

How did Level III Radio come about? How do you view the importance of curation and platforming other DJs?

AR— We had this great space, and we thought, all right, what can we do with this space that adds to the platform that we already have? Dennis and I, for the most part, have a lot of similar musical interests. But we started asking, what are things that I like? What are the things that he likes? And how can we put those together?

We were coming home from our day jobs and just putting DJs on our TV and sitting there and listening and being like, what do you think about this one? Why do you like this DJ? Why is this DJ better than this other DJ? Why should we have this DJ versus that DJ? We began to see the radio as a platform to put together our musical interests when it comes to the DJ scene in New York specifically, and integrate them in a way where the Level III audience gets to see where Ant, Dennis, and anybody else think the sound in the city is going.

And this episode isn't out yet, but there's this Dominican DJ that we brought on called Fried Platano, and he has a really big following within his community. I’m Dominican, and he played some stuff that I personally hadn't heard before. So I reached out, and he came on and did the radio show, and rocked it. It was amazing. I showed him the song he put me on to, and told him, “I owe you for showing me this because you just brought me into a whole different music scene that I hadn't known about. Thank you for that.”

It's something that I hope that people think when they hear Level III Radio. I hope we’re able to contribute to others what he contributed to us.

DF— Halfmoon BK was the platform that I got started on. Originally the show was just me doing mixes and the like. It would play on Saturday afternoons. I wanted a platform for me to be able to showcase my range of sounds across the board, in a more mellow, low-tempo type of space.

But then I thought about all these DJs in the community that I love to go watch and see perform, or who have done shows for us before. I think that being able to showcase their sound in a controlled environment with our audience was something that a lot of people haven't experienced yet, because we had posted sets from the live events that we had done but in live events DJs will come and they'll obviously try to contour their sound in the middle ground between what they like and what the audience may like. So to me, it wasn't as authentic as they could possibly be. I wanted to be able to give them that platform to be able to just do whatever they wanted to do, and every DJ so far has done that. Almost every set that we've had is completely different genre-wise.

The coolest part for me is that both of us are genuine fans of these DJs. They're not necessarily massive touring DJs, but every single person on there, when they start playing, I'm literally gonna stop everything I'm doing to listen because I think they're one of the best DJs that I personally know. There's so many people who are seriously dedicated to their craft.

And we're very young too compared to the majority of the DJs that have been on the show. We're both 23, and the majority of people who are on there are at least 26 or 27, if not older, so we feel very humbled in those settings. These are pros at their game. I'm learning more from them than they are from us, absolutely.