Diplo: Making Love Out Of Nothing At All

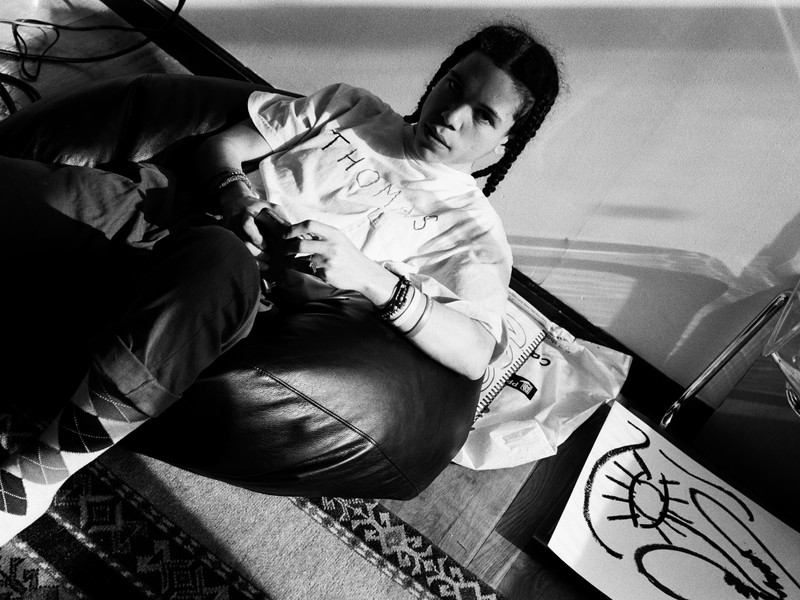

Sunglasses FLATLIST, jacket LOUIS VUITTON

What are your earliest music memories?

I think my first memory was when my mom and dad took me to the Miami Seaquarium when I was eight or nine. I remember hearing breakdance music, like electro, and wanting to be a breakdancer. So, I was breakdancing in the hallway of the orca whale exhibit—there was an intermission and I started to breakdance on the staircase, and there were people watching and clapping for me. I was so bad, but it was like, Well, it's a little kid dancing. But that was about it. I was really into Miami bass and electro music when I was young, living in Florida—it was on the radio a lot, so I was always hearing it. And then I started learning what hip-hop was and how it was made. Hip-hop is such a cool gateway drug to everything because once you understand the production-side of it, you're like, Whoa, this music is actually all this crazy shit, so it becomes your class, your lessons every day when you're learning about music. It teaches you all these different things.

What about your parents? Were they into music?

My parents only had country records and Christian records—they were not into music at all. My dad's only CD was Air Supply. It was literally the one CD he owned. And I actually fucking love Air Supply because of that. I had to re-dig out as an adult and I was like, Damn, this band is so good. But I don't think music ever seemed like a viable source of income or a lifestyle for me—I just loved it. And all my extracurricular activities were music, trying to play piano without lessons, trying to buy electronic equipment without any money, shoplifting drum machines from Sam Ash, falling asleep in my bed with a Doctor Rhythm and headphones on to program drums, things like that. Just learning anything I could, finding the tools to create. When I think about it now, they were so rudimentary, and now, all the access you have with crazy MP3s and synthesizers and DAWs and making music in Oculus… Fuck, I only did this 20 years ago and it was so much more rudimentary—nobody was teaching you how to do anything. You had to download a program, steal the plugins, then learn how to do it on your own. So, I was a late bloomer. I didn't really put out any music until I was 24.

In reality, that’s not late at all, it’s just that now, 14 year olds are dropping their shit on YouTube.

Yeah, the new reality is you can do it at 11 years old. There's a kid on YouTube that I hate, a nine-year-old who plays guitar and covers hip-hop songs. Everyone sends me his videos. I'm like, Stop sending me this guy's shit. I fucking hate this kid. It’s just so different now. I was already trying to do what I loved, but I didn't have any money. At 24 is the moment where I said, You know what? I’m going to quit my job and just jump off the deep end. Because it really is like that—you have no support from your family, you live somewhere, you have to pay your rent, and if you're going to quit your job… I was like, Damn, I might be homeless in a couple of months.

What was your job?

I had bounced between taking tickets at a movie theater to working at Subway. By the time I was 24, I had a pretty decent job—I was a social worker in Philly and I was working with kids. So, it was fulfilling at least. I didn't feel like I was wasting my time by making sandwiches, which is just a nightmare for me as a person. I was like, What is working? If you're not doing something for yourself—I never could understand the fundamentals. What is work? Why would I go to a Subway and put on a jacket to make the guy that owns Subway millions of dollars and risk getting shot every night, because this was in Orlando and we got robbed 16 times. It was just like, What's the point? What is this? I couldn’t understand it until I was like, Fuck it. I'll just do it, even if I make no money, even if I make t-shirts and sell them myself, that's going in my pocket. And so, my record collecting—I turned that into a job. I was selling records and bootlegging records and CDs, and making mixtapes and bootlegging those. I was the guy you used to find on the corner selling music, stealing from the record labels. And then I was selling my own shit. I was looking at 50 Cent and I was like, Damn, this guy did 100,000 in CD sales with no label. And I did the same thing with MIA, but I met her and that was really the beginning of my career.

I’m sort of the same way, I’d rather be homeless and at least doing something that's enjoyable than going to an office every day and sitting in a cubicle and wanting to kill myself. But I feel like it takes—brave is not the right word, maybe it's crazy. It takes a certain type of person to be willing to just put themselves out there, let alone rely on it as your way to live.

Don’t get me wrong, some people love their job. And if we didn't have engineers and social workers and doctors and lawyers that work for the greater good or to create business opportunities for the people, we’d be fucked. But some people, they love the idea of a job, and growing and charging your way up there. That just did not work with my life, and I just felt like I could never compete with people to be better at a job. I could only be the best me. I learned that from skateboarding, because it's not really a competition. Every time you skate, you do something better and better, but it's your style that separates you from everybody else. It was just such a different world. But don't get me wrong, people can be in the ‘rat race’ and actually enjoy themselves… I just never did. I'd rather be broke and happy than working for somebody else, you know?

So, you were into skateboarding growing up. You were into punk too, right?

Yeah. I think if you're from the middle class, that's what you get—you get skating, you get surfing. Surfing was not cool when I was younger—I’m such a big surfer now—but when I was young, it was kind of a dorky thing to do, especially if you were a skater. Now that they've toned down the marketing a little bit—maybe that was the issue. The marketing was so cheesy—it was like Hawaiian tropic girls—and skating was like, Fuck everybody, we fucking run the cities, we jump over you, we wear baggy clothes and listen to punk music, and I was like, Yes, sign me up. And while I was never good at it, it pushed me forward in music, because I loved the way that music and skating combined. When you buy a skate video, I was like, What is this shredding? That’s corny. But if they're skating to that music, that's cool as fuck. And I valued every kind of music because of skating. You can put any fucking song with a sick skateboarding routine and it's like, the coolest song you've ever heard. A lot of time it was punk, then it was A Tribe Called Quest, it could even be Air Supply. They would really push the envelope with how far it could go. And when you put music into a perspective or when you put it into a culture, the value of music is endless. Skating helps break down any prejudice you have on what music is, and what culture is, and what people are supposed to do, and what they can do, and what things can mean to certain people.

When it comes to punk—and even skating—what was it about the culture that was so attractive to you? Was it the attitude?

Yeah, I went through a lot of phases trying to figure out what I loved about it. In Daytona—that's where my family is from, but I grew up in Fort Lauderdale—ska and punk were massive, and I just was really into it, because the only shows in town were at the church which had punk shows every week. And I just loved the nature of people dressing fucking cool—as much as you can hate ska, it was the coolest looking people around. I'm talking punk ska, No Doubt being the biggest band in that world, but there's so many smaller bands, like The Hippos and shit like that. I actually got into like old ska because of that and experimenting with music even further. And with punk, it just was like, Fuck everybody. I was kind of a bad kid and I moved to a lot of high schools. I think my parents moved me around a lot because they knew I was going to end up doing something bad. I was even in military school for a little while. I was a nightmare, but when you have to move high schools so many times you never can click up and be bad. You have nobody to impress anymore, so you just have to be yourself. And that's when I got really creative—when I was alone. I was like, Fuck it. This is a way to express myself more than shoplifting.

Right. You're talking about all these different types of music you were attracted to, even from a young age. Do you think that kid who’s just curious and wants to and experience everything—do you think that's still part of your process?

I think when I was younger, I was never bad in school, but I just didn't also understand, why am I learning about Calculus? When am I going to use this? Why do I have to be good at this? And it was like, I struggle to force myself to do work and think why is this important? But with music, I would pick up a record, I'd look over the back, I would find out about the people who wrote the records, I would study their life and what they did. And I couldn't get enough. Just learning about music and learning why is this like this? Why is Iggy Pop from Detroit? Why are they making this music in LA? Where did Mississippi Blues come from? This is the real, concrete information that's not going to change. I would spend all my time buying records and learning. This is before the internet, so I literally had to go to record shops and listen to music to figure it all out. I was the most annoying person there. I would get every record, listen to every part of it in the shop, not buy it and then go on Soulseek and steal it. I always found a way to make it work for me. Just learning and knowing so much history of music… It gave me a reason to live. I think in that ethos, what I'm doing now, yeah… I mean, I'm a DJ. I found the medium that works the most for me. But I'm still always exploring, I'm still always learning. I just put out a new record. It's all basically dance and house music, but I put everybody I could on it to shake up the scene. I have underground techno producers that usually wouldn't work on a record with me, I have Lil Yachty on it, I have TSHA, I have Leon Bridges on a song. I just always try to make everything I possibly can to confuse people, but make it so it's coherent, too. That's my as a DJ or a producer, I'm like, How can I fuck this up so bad and still have it make sense?

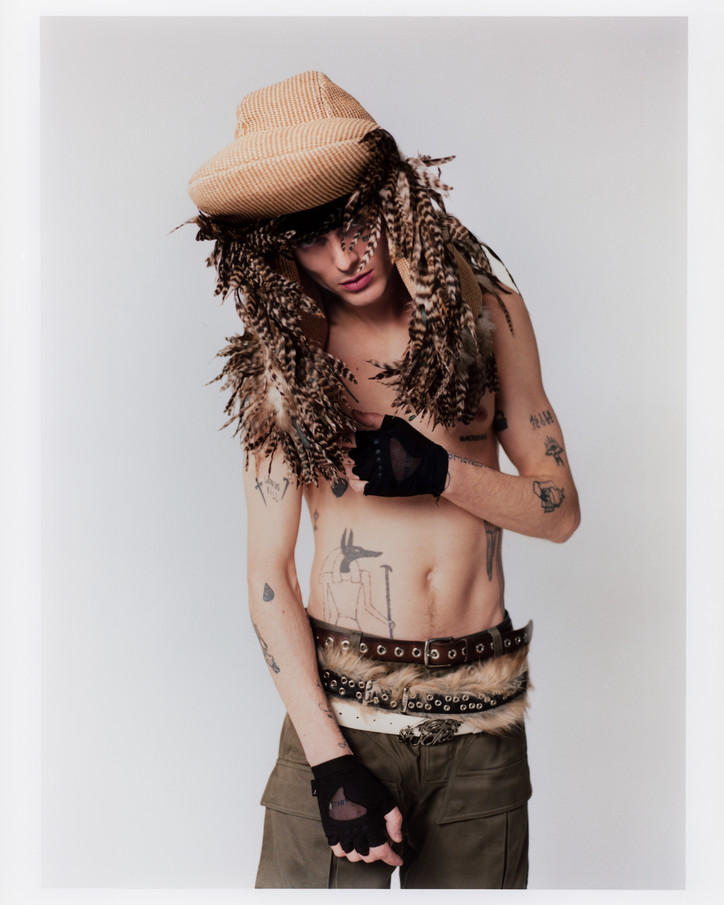

Left: Hat TALENT'S OWN. Right: Jacket COACH, shorts AIRES, shoes CROCS x SALEHE BEMBURY, sunglasses FLATLIST

That idea of you going to the record store and like you said, just wanting to figure everything out—that has been a big part of your career. Going to Brazil and bringing favela funk into your music, going to Jamaica and discovering dancehall… Is music a kind of cultural anthropology for you?

I think so. Actually when I went to college, I went for anthropology. I moved to Philly because they had a good anthropology program and that was the only thing I wanted to learn. My dad was so fucking pissed. He was like, ‘What the fuck is this shit? What are you doing? Go be an accountant or something!’ But I was like, Nah, this is what I want to do. I ended up dropping out of college anyway, and I wish I’d dropped out sooner, but I went there and I studied culture. Everything about what makes humans humans is just exciting to me. So, when I read about people talking about cultural appropriation, I'm just like, they don't have any idea what the fuck they're talking about. I went to the best school for anthropology and I know that culture has no boundaries. What people do is what they do. It's such an infinite possibility that humans have. And I think it's the biggest joke when people try to put rules on what things are okay. But that’s always fascinated me—I loved pushing the boundaries from the beginning. Let's go to Jamaica, let's make electronic music there. Let's go to Brazil, let's see what the kids do there, the punks. Punk to me was like, just fucking things up. Metal and Samba music together? Let’s do it. Whatever it is, I was like, What are the rules? Let's fucking break them. And I think that's what the people who are exciting to me always did, like The Clash. They moved to New York and they made disco funk and hip-hop. David Bowie was 44 when he made records with Nile Rodgers, and he shouldn't have done that. He was a glam, bisexual, rocker guy. Everybody who did things that broke the fucking mold, I was like, That's my family—they are who I learned from.

Speaking of cultural appropriation, that’s obviously something that has followed you for your whole career. And right now especially, as a culture, we’re asking questions about who gets to make what kind of art. What do you think?

There are no rules in music. That’s my opinion. Our art doesn't—and shouldn’t—have any fucking rules. Literally the only rule is how it applies to you as an audience and you alone, you can't apply your feelings to somebody else. If art makes you feel something, the artist’s job is done. That’s it. If you have an opinion about it, that's up to you, as well. But you can't form an opinion for other people. This girl has the wrong hair color, don’t listen to her. Or you shouldn't listen to that because he's not from Africa, or you should listen to that because he is from Africa, or you shouldn't listen to that because he came from a rich family—whatever it is—all those things should melt away with art. Because it’s like, when the music touches you, did you think about that? If you close your eyes and you listen to a great song, do you think about where it came from? When I worked with Justin Bieber for the first time—well, we worked on a lot of records back in his early career, but our first record we put out with him was called “Where Are Ü Now” with me, him and Skrillex—it was a fucking challenge to get everybody on board. At the time, Justin Bieber was one of the least liked artists in the world. And that seems hard to believe now, but you know what I'm talking about—remember that era of Justin Bieber Tattoos and going to jail, smoking weed and talking dirty. We had this demo and I was like, Let's fucking do this. And I remember being in Ibiza at a show randomly—some shitty show where I was opening up for David Guetta and probably got paid a hundred dollars—and we were listening to this radio show where they were doing things like a ‘Is this song hot or not?’ thing, and they played some shitty Dutch house record, which got voted ‘Hot,’ and then they played “Where Are Ü Now,” and the song got unanimously voted off. I was like, This fucking sucks. But then that record ended up going so crazy. It was my first platinum record as a producer for all my own music, and it basically rewrote what people thought about Justin Bieber, because people, no matter what their opinion was about him, the song was fire.

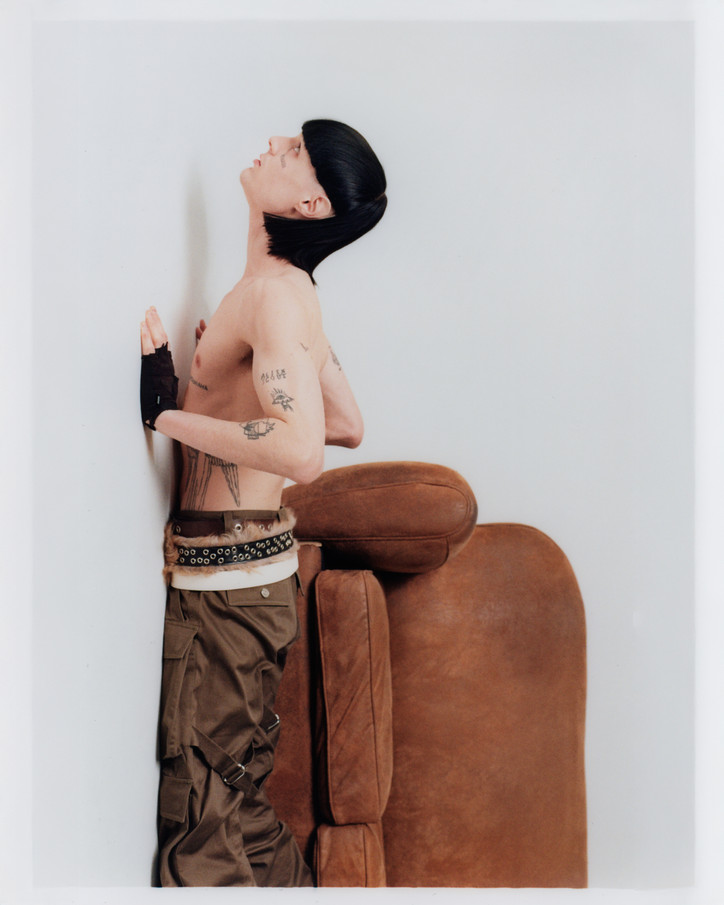

Left: Coat and pants BURBERRY, top CALVIN KLEIN, sunglasses FLATLIST. Right: Sweater R-13, pants BALENCIAGA, shoes VANS, hat TALENT’S OWN

Right.It was just undeniable.

Yeah, that's the point—it’s undeniable. Another thing about cultural appropriation, too, I grew up studying and learning about music because I was fascinated by it. So, I do attribute my skill or whatever to my knowledge of music, to the history and the love I have for it. And if you don't understand the idiosyncrasies of why we are like this, or if you don't understand social economic history, well, maybe you should learn that, because there are reasons why things are formed the way they are. That's what I learned as an anthropologist—I learned why people do what they do and why they create what they do. Why is there polka music called Norteña in Mexico? Because German immigrants moved there and settled some houses. They brought their fucking accordions, and started making music. But you wouldn't know that now because you just see dudes in mariachi outfits singing fucking polka music in Spanish. A lot of people don’t want to know why—and you don’t have to, to enjoy it—but I was always like, Why is it like this? Where did it come from? I think that's something people should understand. But at the end of the day, if it makes you feel some way, it does. If it doesn't, turn it off, go to the next thing. You don't have to always share your opinion.

That desire to break these rules, or even just your interest in culture and humanity—is that why you've decided to play in places like Cuba, where art has been censored?

Yeah, Cuba is isolated because they really, literally don't have access. I think it's the only place in the world that truly exists like that. Like, when I went to Pakistan, the biggest song I played was “Gucci Gang" by fucking Lil Pump, and it had just came out two weeks before. So, people do find music, they find art. Kids always find a way to break the rules. You could live in fucking Siberia, but your mother and father have a favorite hip-hop song. But Cuba, I had to literally have a team pass out USB keys to people to make them know what my music sounded like. The other places I go, like Pakistan, or Nigeria, or wherever… They don’t pay any money, and that’s why you go on tour—to make money. But I go places where I don't make money because I want to work with these people, I want to build and I want to learn, I want to go there and spend my energy making records with people. That's really my motivation for traveling.

You mentioned Justin Bieber and how he was really disliked at some point, and it's funny, when you Google ‘Diplo,’ you see all these headlines calling you ‘pop’s problem child,’ or calling you a villain. I'm curious why you think people think of you that way?

I think I went south around the advent of Twitter, and then my public beef with my girlfriend at the time, MIA, and my beef with Taylor Swift, which was just stupid. I just didn't realize my sarcasm was taken as real at the time, and I know now… I don't even use Twitter. Middle-aged white guys just don't belong on Twitter. I'm on SoundCloud and Instagram and TikTok—TikTok, especially, because I’m just like, Whatever, I'll be stupid. But in the beginning, yeah, I think I was a villain because of all of that, which I know is an easy answer to say, but I think for the most part also, when we talk about cultural appropriation, I really never thought it was weird what I was doing, because the people I listened to, and how I learned about music, like Afrika Bambaataa, or The Wizard in Detroit, or like I said, Bowie—listening to them, I never thought there were rules. Bambaataa brought German music to The Bronx and it changed the world forever. He played Kraftwerk records and sampled them to make "Planet Rock,” and made the biggest anthem of all time. That fusion created the music that I listened to. I mean, my career wouldn't exist if it wasn't for Miami bass and electro. So, when I learned about that, I was like, This is fucking sick. But why is there not more chaos? That's the best thing that ever happens to art. So, I'm not going to win any arguments about what am I supposed to do as a middle-aged, cisgender white guy from Florida. It’s cool. But when it comes to explaining what music does to you, I'll always win because it's from my heart. And the people that want to write a hit piece on me about cultural appropriation—it’s just so tired. It's so old. I've been in Jamaica for 20 years making music with Vybz Kartel. I’m intertwining all these societies, no matter how much you want to hate me. I'm part of it. And I've been doing it and I'm not going to stop. Maybe that's an easy answer. If you want to do a roundtable with a bunch of haters, they’d probably say something else.

When it comes to your new album, I've heard it described as ‘the first proper Diplo album since 2004,’ or as your return to dance music… What does that mean? What's a proper Diplo album?

That’s one-hundred percent a marketing term from my lazy label. I mean, it really makes sense on paper, but I've done a million different albums, just under different names. I legally had the right to do a Diplo album right now, so we decided to do that. And I'll tell you, honestly, dance album’s not really the right term—I wouldn't even consider it an album, I don't think albums even really exist anymore. Maybe The Weeknd—he’s really conceptual, the last guy left that's trying to do that. But for me, it's just a bunch of dance records I put out and then you add some old ones, so you can get better number placement in the first week. Like, “On My Mind” came out four years ago. So, it's just an industry plant created concept. But I do think it's the first time I ever did an album and am spending my energy marketing it and like, doing press photos. I don't really do that anymore. So, hopefully people like it. I'm already, as a producer, because I work so fast—I’m already working on the next thing. I'm going to move genres to South African gospel music now. I'm such a psychopath still. I move so quick.

Does dance music really exist anymore, though? Pop and dance have become so intertwined, whereas when you put out your first record, there weren't a lot of pop artists collaborating with dance artists on a dance track.

Well, there was a wave of dance and pop guys. Like, if Selena Gomez has a bunch of records and she's scared to put them out by herself, I'll give them to Kygo and he'll take the blame if they're bad. That was the marketing idea that labels had—like, DJ Snake, here's a bunch of songs from Cardi B. You can put this out because we don't want to do it. And if you make money, we all make money. So, it was this lazy era that I'm a part of. I started it with “Lean On”—we didn't have a pop singer on it, but it was the first, let's say pop song with electronic production, and we did that. It was independent. And it was the first international number one dance record like that. So, everybody was like, Fuck, this is the cheat code. That came and went quick—you can't even put features out with stars anymore. No one gives a shit. You need TikTok behind you. You need all this shit backing you up. So, the best thing you can do is just keep putting out fucking great records and hope that they find that spark that they need to get blow up. But, yeah, dance music still exists. I made this album as the pop producer that I am. So, they’re pop songs, they’re structured songs, there’s a lot of vocals. But that's what I do as a solo artist. I understand pop. I understand verses and choruses. I could just make straight tech house records, but this is my streaming project—it’s music that I think is a lot more palatable. Don’t get me wrong, there’s still dance music there, and some of the people on the album, it might have been a stretch for them to be on it, but that idea of genre in dance music alone has been broken down. Everybody was like, Fuck, there’s pandemic, what was that conversation? What was this beef about? Let's just fucking make music. And I'm so happy about all the different people I got to be on the record, because even five years ago, they would be like, Fuck that. There were all these unwritten rules of techno and house… Even Mark Ronson, before we did our collaboration, the guy would never have worked with me! He’s been my good friend for years, but he's so busy thinking about what NME cares about that he wasn’t caring about what’s exciting. A lot of these guys have this mentality about critics and they want their score to be so high because they want to go down in history with the most Emmys and Tonys or whatever. But I'm just like, Let's fucking make as much noise as possible. Who cares? And eventually, if I make a hundred songs, one's going to go on TikTok, or one's going to get nominated for a Grammy. My thought process is definitely quantity over quality, which is probably the worst way to work, but that's what I do.

So, it’s a numbers game for you.

It is. Well, nowadays it is. I was forced into that mentality. I didn't want to be like that, but the streets made me who I am.

You do so much different work—you’re a pop producer, you're a solo artist, you're a DJ. Then you've got LSD and Silk City. Are all of these different projects just a way for you to express yourself differently, or geek out over something that wouldn't work for your work in one of your roles? Or is it really just that you’re making as much stuff as you can?

Most times, I'm just sneaking into people's lives. Like Skrillex—I’m like, Who's the best producer in the world? It's Skrillex, so let's make a collaboration. I'll give him something he didn't have. I have this unique skill of writing pop songs—that’s the one thing I'm good at. I'm not the best electronic producer, I’m definitely not the best fucking musician, but I have a quirky way of understanding songwriting. So, that’s my way to sneak in. I was like, Fuck, I'm going to learn from Skrillex and make the sickest record we could with my ideas because I can't make them myself. And then maybe it's Mark Ronson—everyone wants to collaborate with him. He's the fucking GOAT. So, it’s just another way for me to learn. Every one of these projects is me literally going back to grad school with each project. That's really how I feel.

But you also work with a lot of emerging artists, as well.

My biggest records have been with emerging artists, weirdly enough, because there's nothing to be expected. The biggest song I've ever done was “Lean On” with MØ, who’s a Danish, like, jazz singer. And it just worked. I tried to give that song to Rihanna. I tried to give it to Nick [Minaj]—I couldn't give that record away. I was like, This is a fucking smash, and it obviously was, but we were like, Fuck it, we'll sing it ourselves. That's where I ended up as a producer. I want to farm all my records out to everybody, but I'm also not a bitch. When you want to work with Post Malone—who’s the homie I love to death—you’ve literally got to follow that guy around to Utah, to a studio and drink lean until like 7AM, hanging out with a bunch of girls and playing beer pong for 56 hours. I would've done that five years ago or 10 years ago, but I just can't do that anymore. Now, I’m just like, Here’s my record. If you like it, please give it a chance. If you don’t, I'm not going to go fucking ride four wheelers over a cliff with you and drink Bud Light. Maybe I would—with Post I definitely would, if he asked me to—but I'd rather go to fucking Africa on tour. I don't want to fucking sit in the studio and maybe my heart will stop beating from doing so many fucking drugs. I’ll just put them out myself. That's basically how this album got made—it’s a bunch of dance records nobody wanted, and I just said, Well, fuck it, I’ll put them out. That's basically my whole career.

Left: Jacket DIESEL, shorts 7DAYS ACTIVE, sunglasses GENTLE MONSTER. Right: Jacket and pants LOUIS VUITTON

Left: Jacket DIESEL, shorts 7DAYS ACTIVE. Right: Pants LOUIS VUITTON

What was your job?

I had bounced between taking tickets at a movie theater to working at Subway. By the time I was 24, I had a pretty decent job—I was a social worker in Philly and I was working with kids. So, it was fulfilling at least. I didn't feel like I was wasting my time by making sandwiches, which is just a nightmare for me as a person. I was like, What is working? If you're not doing something for yourself—I never could understand the fundamentals. What is work? Why would I go to a Subway and put on a jacket to make the guy that owns Subway millions of dollars and risk getting shot every night, because this was in Orlando and we got robbed 16 times. It was just like, What's the point? What is this? I couldn’t understand it until I was like, Fuck it. I'll just do it, even if I make no money, even if I make t-shirts and sell them myself, that's going in my pocket. And so, my record collecting—I turned that into a job. I was selling records and bootlegging records and CDs, and making mixtapes and bootlegging those. I was the guy you used to find on the corner selling music, stealing from the record labels. And then I was selling my own shit. I was looking at 50 Cent and I was like, Damn, this guy did 100,000 in CD sales with no label. And I did the same thing with MIA, but I met her and that was really the beginning of my career.

I’m sort of the same way, I’d rather be homeless and at least doing something that's enjoyable than going to an office every day and sitting in a cubicle and wanting to kill myself. But I feel like it takes—brave is not the right word, maybe it's crazy. It takes a certain type of person to be willing to just put themselves out there, let alone rely on it as your way to live.

Don’t get me wrong, some people love their job. And if we didn't have engineers and social workers and doctors and lawyers that work for the greater good or to create business opportunities for the people, we’d be fucked. But some people, they love the idea of a job, and growing and charging your way up there. That just did not work with my life, and I just felt like I could never compete with people to be better at a job. I could only be the best me. I learned that from skateboarding, because it's not really a competition. Every time you skate, you do something better and better, but it's your style that separates you from everybody else. It was just such a different world. But don't get me wrong, people can be in the ‘rat race’ and actually enjoy themselves… I just never did. I'd rather be broke and happy than working for somebody else, you know?

So, you were into skateboarding growing up. You were into punk too, right?

Yeah. I think if you're from the middle class, that's what you get—you get skating, you get surfing. Surfing was not cool when I was younger—I’m such a big surfer now—but when I was young, it was kind of a dorky thing to do, especially if you were a skater. Now that they've toned down the marketing a little bit—maybe that was the issue. The marketing was so cheesy—it was like Hawaiian tropic girls—and skating was like, Fuck everybody, we fucking run the cities, we jump over you, we wear baggy clothes and listen to punk music, and I was like, Yes, sign me up. And while I was never good at it, it pushed me forward in music, because I loved the way that music and skating combined. When you buy a skate video, I was like, What is this shredding? That’s corny. But if they're skating to that music, that's cool as fuck. And I valued every kind of music because of skating. You can put any fucking song with a sick skateboarding routine and it's like, the coolest song you've ever heard. A lot of time it was punk, then it was A Tribe Called Quest, it could even be Air Supply. They would really push the envelope with how far it could go. And when you put music into a perspective or when you put it into a culture, the value of music is endless. Skating helps break down any prejudice you have on what music is, and what culture is, and what people are supposed to do, and what they can do, and what things can mean to certain people.

When it comes to punk—and even skating—what was it about the culture that was so attractive to you? Was it the attitude?

Yeah, I went through a lot of phases trying to figure out what I loved about it. In Daytona—that's where my family is from, but I grew up in Fort Lauderdale—ska and punk were massive, and I just was really into it, because the only shows in town were at the church which had punk shows every week. And I just loved the nature of people dressing fucking cool—as much as you can hate ska, it was the coolest looking people around. I'm talking punk ska, No Doubt being the biggest band in that world, but there's so many smaller bands, like The Hippos and shit like that. I actually got into like old ska because of that and experimenting with music even further. And with punk, it just was like, Fuck everybody. I was kind of a bad kid and I moved to a lot of high schools. I think my parents moved me around a lot because they knew I was going to end up doing something bad. I was even in military school for a little while. I was a nightmare, but when you have to move high schools so many times you never can click up and be bad. You have nobody to impress anymore, so you just have to be yourself. And that's when I got really creative—when I was alone. I was like, Fuck it. This is a way to express myself more than shoplifting.

Right. You're talking about all these different types of music you were attracted to, even from a young age. Do you think that kid who’s just curious and wants to and experience everything—do you think that's still part of your process?

I think when I was younger, I was never bad in school, but I just didn't also understand, why am I learning about Calculus? When am I going to use this? Why do I have to be good at this? And it was like, I struggle to force myself to do work and think why is this important? But with music, I would pick up a record, I'd look over the back, I would find out about the people who wrote the records, I would study their life and what they did. And I couldn't get enough. Just learning about music and learning why is this like this? Why is Iggy Pop from Detroit? Why are they making this music in LA? Where did Mississippi Blues come from? This is the real, concrete information that's not going to change. I would spend all my time buying records and learning. This is before the internet, so I literally had to go to record shops and listen to music to figure it all out. I was the most annoying person there. I would get every record, listen to every part of it in the shop, not buy it and then go on Soulseek and steal it. I always found a way to make it work for me. Just learning and knowing so much history of music… It gave me a reason to live. I think in that ethos, what I'm doing now, yeah… I mean, I'm a DJ. I found the medium that works the most for me. But I'm still always exploring, I'm still always learning. I just put out a new record. It's all basically dance and house music, but I put everybody I could on it to shake up the scene. I have underground techno producers that usually wouldn't work on a record with me, I have Lil Yachty on it, I have TSHA, I have Leon Bridges on a song. I just always try to make everything I possibly can to confuse people, but make it so it's coherent, too. That's my as a DJ or a producer, I'm like, How can I fuck this up so bad and still have it make sense?

That idea of you going to the record store and like you said, just wanting to figure everything out—that has been a big part of your career. Going to Brazil and bringing favela funk into your music, going to Jamaica and discovering dancehall… Is music a kind of cultural anthropology for you?

I think so. Actually when I went to college, I went for anthropology. I moved to Philly because they had a good anthropology program and that was the only thing I wanted to learn. My dad was so fucking pissed. He was like, ‘What the fuck is this shit? What are you doing? Go be an accountant or something!’ But I was like, Nah, this is what I want to do. I ended up dropping out of college anyway, and I wish I’d dropped out sooner, but I went there and I studied culture. Everything about what makes humans humans is just exciting to me. So, when I read about people talking about cultural appropriation, I'm just like, they don't have any idea what the fuck they're talking about. I went to the best school for anthropology and I know that culture has no boundaries. What people do is what they do. It's such an infinite possibility that humans have. And I think it's the biggest joke when people try to put rules on what things are okay. But that’s always fascinated me—I loved pushing the boundaries from the beginning. Let's go to Jamaica, let's make electronic music there. Let's go to Brazil, let's see what the kids do there, the punks. Punk to me was like, just fucking things up. Metal and Samba music together? Let’s do it. Whatever it is, I was like, What are the rules? Let's fucking break them. And I think that's what the people who are exciting to me always did, like The Clash. They moved to New York and they made disco funk and hip-hop. David Bowie was 44 when he made records with Nile Rodgers, and he shouldn't have done that. He was a glam, bisexual, rocker guy. Everybody who did things that broke the fucking mold, I was like, That's my family—they are who I learned from.

Speaking of cultural appropriation, that’s obviously something that has followed you for your whole career. And right now especially, as a culture, we’re asking questions about who gets to make what kind of art. What do you think?

There are no rules in music. That’s my opinion. Our art doesn't—and shouldn’t—have any fucking rules. Literally the only rule is how it applies to you as an audience and you alone, you can't apply your feelings to somebody else. If art makes you feel something, the artist’s job is done. That’s it. If you have an opinion about it, that's up to you, as well. But you can't form an opinion for other people. This girl has the wrong hair color, don’t listen to her. Or you shouldn't listen to that because he's not from Africa, or you should listen to that because he is from Africa, or you shouldn't listen to that because he came from a rich family—whatever it is—all those things should melt away with art. Because it’s like, when the music touches you, did you think about that? If you close your eyes and you listen to a great song, do you think about where it came from? When I worked with Justin Bieber for the first time—well, we worked on a lot of records back in his early career, but our first record we put out with him was called “Where Are Ü Now” with me, him and Skrillex—it was a fucking challenge to get everybody on board. At the time, Justin Bieber was one of the least liked artists in the world. And that seems hard to believe now, but you know what I'm talking about—remember that era of Justin Bieber Tattoos and going to jail, smoking weed and talking dirty. We had this demo and I was like, Let's fucking do this. And I remember being in Ibiza at a show randomly—some shitty show where I was opening up for David Guetta and probably got paid a hundred dollars—and we were listening to this radio show where they were doing things like a ‘Is this song hot or not?’ thing, and they played some shitty Dutch house record, which got voted ‘Hot,’ and then they played “Where Are Ü Now,” and the song got unanimously voted off. I was like, This fucking sucks. But then that record ended up going so crazy. It was my first platinum record as a producer for all my own music, and it basically rewrote what people thought about Justin Bieber, because people, no matter what their opinion was about him, the song was fire.

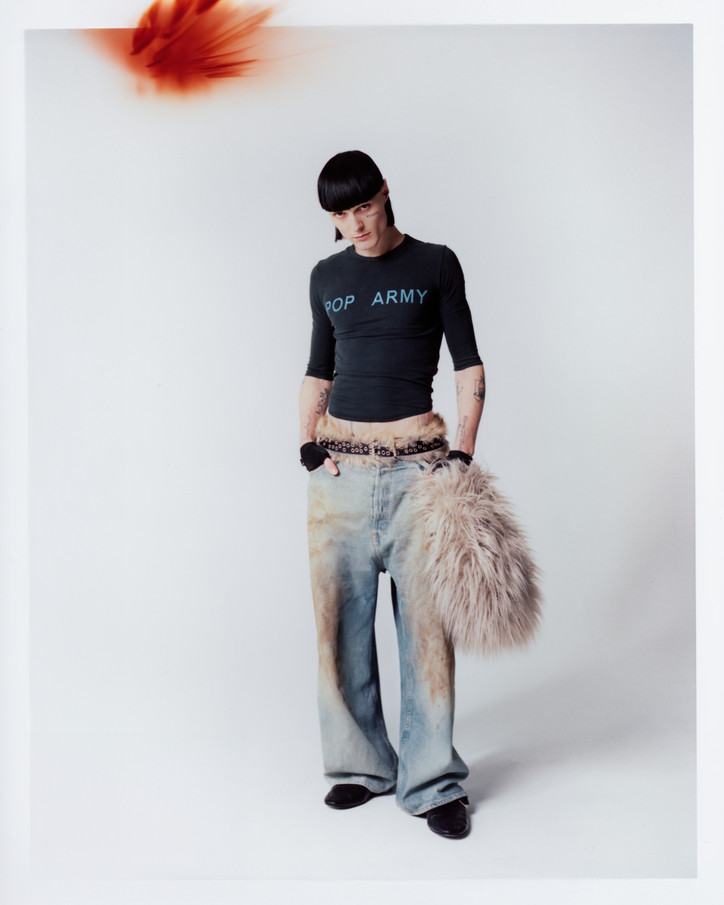

Shirt VERSACE, jeans and boots Y/PROJECT, hat TALENT’S OWN

Right. It was just undeniable.

Yeah, that's the point—it’s undeniable. Another thing about cultural appropriation, too, I grew up studying and learning about music because I was fascinated by it. So, I do attribute my skill or whatever to my knowledge of music, to the history and the love I have for it. And if you don't understand the idiosyncrasies of why we are like this, or if you don't understand social economic history, well, maybe you should learn that, because there are reasons why things are formed the way they are. That's what I learned as an anthropologist—I learned why people do what they do and why they create what they do. Why is there polka music called Norteña in Mexico? Because German immigrants moved there and settled some houses. They brought their fucking accordions, and started making music. But you wouldn't know that now because you just see dudes in mariachi outfits singing fucking polka music in Spanish. A lot of people don’t want to know why—and you don’t have to, to enjoy it—but I was always like, Why is it like this? Where did it come from? I think that's something people should understand. But at the end of the day, if it makes you feel some way, it does. If it doesn't, turn it off, go to the next thing. You don't have to always share your opinion.

That desire to break these rules, or even just your interest in culture and humanity—is that why you've decided to play in places like Cuba, where art has been censored?

Yeah, Cuba is isolated because they really, literally don't have access. I think it's the only place in the world that truly exists like that. Like, when I went to Pakistan, the biggest song I played was “Gucci Gang" by fucking Lil Pump, and it had just came out two weeks before. So, people do find music, they find art. Kids always find a way to break the rules. You could live in fucking Siberia, but your mother and father have a favorite hip-hop song. But Cuba, I had to literally have a team pass out USB keys to people to make them know what my music sounded like. The other places I go, like Pakistan, or Nigeria, or wherever… They don’t pay any money, and that’s why you go on tour—to make money. But I go places where I don't make money because I want to work with these people, I want to build and I want to learn, I want to go there and spend my energy making records with people. That's really my motivation for traveling.

You mentioned Justin Bieber and how he was really disliked at some point, and it's funny, when you Google ‘Diplo,’ you see all these headlines calling you ‘pop’s problem child,’ or calling you a villain. I'm curious why you think people think of you that way?

I think I went south around the advent of Twitter, and then my public beef with my girlfriend at the time, MIA, and my beef with Taylor Swift, which was just stupid. I just didn't realize my sarcasm was taken as real at the time, and I know now… I don't even use Twitter. Middle-aged white guys just don't belong on Twitter. I'm on SoundCloud and Instagram and TikTok—TikTok, especially, because I’m just like, Whatever, I'll be stupid. But in the beginning, yeah, I think I was a villain because of all of that, which I know is an easy answer to say, but I think for the most part also, when we talk about cultural appropriation, I really never thought it was weird what I was doing, because the people I listened to, and how I learned about music, like Afrika Bambaataa, or The Wizard in Detroit, or like I said, Bowie—listening to them, I never thought there were rules. Bambaataa brought German music to The Bronx and it changed the world forever. He played Kraftwerk records and sampled them to make "Planet Rock,” and made the biggest anthem of all time. That fusion created the music that I listened to. I mean, my career wouldn't exist if it wasn't for Miami bass and electro. So, when I learned about that, I was like, This is fucking sick. But why is there not more chaos? That's the best thing that ever happens to art. So, I'm not going to win any arguments about what am I supposed to do as a middle-aged, cisgender white guy from Florida. It’s cool. But when it comes to explaining what music does to you, I'll always win because it's from my heart. And the people that want to write a hit piece on me about cultural appropriation—it’s just so tired. It's so old. I've been in Jamaica for 20 years making music with Vybz Kartel. I’m intertwining all these societies, no matter how much you want to hate me. I'm part of it. And I've been doing it and I'm not going to stop. Maybe that's an easy answer. If you want to do a roundtable with a bunch of haters, they’d probably say something else.

When it comes to your new album, I've heard it described as ‘the first proper Diplo album since 2004,’ or as your return to dance music… What does that mean? What's a proper Diplo album?

That’s one-hundred percent a marketing term from my lazy label. I mean, it really makes sense on paper, but I've done a million different albums, just under different names. I legally had the right to do a Diplo album right now, so we decided to do that. And I'll tell you, honestly, dance album’s not really the right term—I wouldn't even consider it an album, I don't think albums even really exist anymore. Maybe The Weeknd—he’s really conceptual, the last guy left that's trying to do that. But for me, it's just a bunch of dance records I put out and then you add some old ones, so you can get better number placement in the first week. Like, “On My Mind” came out four years ago. So, it's just an industry plant created concept. But I do think it's the first time I ever did an album and am spending my energy marketing it and like, doing press photos. I don't really do that anymore. So, hopefully people like it. I'm already, as a producer, because I work so fast—I’m already working on the next thing. I'm going to move genres to South African gospel music now. I'm such a psychopath still. I move so quick.

Does dance music really exist anymore, though? Pop and dance have become so intertwined, whereas when you put out your first record, there weren't a lot of pop artists collaborating with dance artists on a dance track.

Well, there was a wave of dance and pop guys. Like, if Selena Gomez has a bunch of records and she's scared to put them out by herself, I'll give them to Kygo and he'll take the blame if they're bad. That was the marketing idea that labels had—like, DJ Snake, here's a bunch of songs from Cardi B. You can put this out because we don't want to do it. And if you make money, we all make money. So, it was this lazy era that I'm a part of. I started it with “Lean On”—we didn't have a pop singer on it, but it was the first, let's say pop song with electronic production, and we did that. It was independent. And it was the first international number one dance record like that. So, everybody was like, Fuck, this is the cheat code. That came and went quick—you can't even put features out with stars anymore. No one gives a shit. You need TikTok behind you. You need all this shit backing you up. So, the best thing you can do is just keep putting out fucking great records and hope that they find that spark that they need to get blow up. But, yeah, dance music still exists. I made this album as the pop producer that I am. So, they’re pop songs, they’re structured songs, there’s a lot of vocals. But that's what I do as a solo artist. I understand pop. I understand verses and choruses. I could just make straight tech house records, but this is my streaming project—it’s music that I think is a lot more palatable. Don’t get me wrong, there’s still dance music there, and some of the people on the album, it might have been a stretch for them to be on it, but that idea of genre in dance music alone has been broken down. Everybody was like, Fuck, there’s pandemic, what was that conversation? What was this beef about? Let's just fucking make music. And I'm so happy about all the different people I got to be on the record, because even five years ago, they would be like, Fuck that. There were all these unwritten rules of techno and house… Even Mark Ronson, before we did our collaboration, the guy would never have worked with me! He’s been my good friend for years, but he's so busy thinking about what NME cares about that he wasn’t caring about what’s exciting. A lot of these guys have this mentality about critics and they want their score to be so high because they want to go down in history with the most Emmys and Tonys or whatever. But I'm just like, Let's fucking make as much noise as possible. Who cares? And eventually, if I make a hundred songs, one's going to go on TikTok, or one's going to get nominated for a Grammy. My thought process is definitely quantity over quality, which is probably the worst way to work, but that's what I do.

So, it’s a numbers game for you.

It is. Well, nowadays it is. I was forced into that mentality. I didn't want to be like that, but the streets made me who I am.

You do so much different work—you’re a pop producer, you're a solo artist, you're a DJ. Then you've got LSD and Silk City. Are all of these different projects just a way for you to express yourself differently, or geek out over something that wouldn't work for your work in one of your roles? Or is it really just that you’re making as much stuff as you can?

Most times, I'm just sneaking into people's lives. Like Skrillex—I’m like, Who's the best producer in the world? It's Skrillex, so let's make a collaboration. I'll give him something he didn't have. I have this unique skill of writing pop songs—that’s the one thing I'm good at. I'm not the best electronic producer, I’m definitely not the best fucking musician, but I have a quirky way of understanding songwriting. So, that’s my way to sneak in. I was like, Fuck, I'm going to learn from Skrillex and make the sickest record we could with my ideas because I can't make them myself. And then maybe it's Mark Ronson—everyone wants to collaborate with him. He's the fucking GOAT. So, it’s just another way for me to learn. Every one of these projects is me literally going back to grad school with each project. That's really how I feel.

But you also work with a lot of emerging artists, as well.

My biggest records have been with emerging artists, weirdly enough, because there's nothing to be expected. The biggest song I've ever done was “Lean On” with MØ, who’s a Danish, like, jazz singer. And it just worked. I tried to give that song to Rihanna. I tried to give it to Nick [Minaj]—I couldn't give that record away. I was like, This is a fucking smash, and it obviously was, but we were like, Fuck it, we'll sing it ourselves. That's where I ended up as a producer. I want to farm all my records out to everybody, but I'm also not a bitch. When you want to work with Post Malone—who’s the homie I love to death—you’ve literally got to follow that guy around to Utah, to a studio and drink lean until like 7AM, hanging out with a bunch of girls and playing beer pong for 56 hours. I would've done that five years ago or 10 years ago, but I just can't do that anymore. Now, I’m just like, Here’s my record. If you like it, please give it a chance. If you don’t, I'm not going to go fucking ride four wheelers over a cliff with you and drink Bud Light. Maybe I would—with Post I definitely would, if he asked me to—but I'd rather go to fucking Africa on tour. I don't want to fucking sit in the studio and maybe my heart will stop beating from doing so many fucking drugs. I’ll just put them out myself. That's basically how this album got made—it’s a bunch of dance records nobody wanted, and I just said, Well, fuck it, I’ll put them out. That's basically my whole career.

Left: Shorts 7DAYS ACTIVE, sunglasses GENTLE MONSTER. Right: Dress R-13