For Elise Nguyen Quoc, the Pen Is Mightier Than the Paintbrush

Her work, while somewhat abstract, is not true “abstraction” — the images Nguyen Quoc chooses to paint are what she calls “traces” — leftover, zoomed-in close-ups of photos she has taken. “Every day I see traces and images all around me, left by other people, by animals, by the passing and disintegration of time. My images and my gestures are common — basically I'm just a copyist, not a brilliant artist,” she says. “The better I choose my images, the better they will speak to viewers and (indirectly) put me in touch with others.”

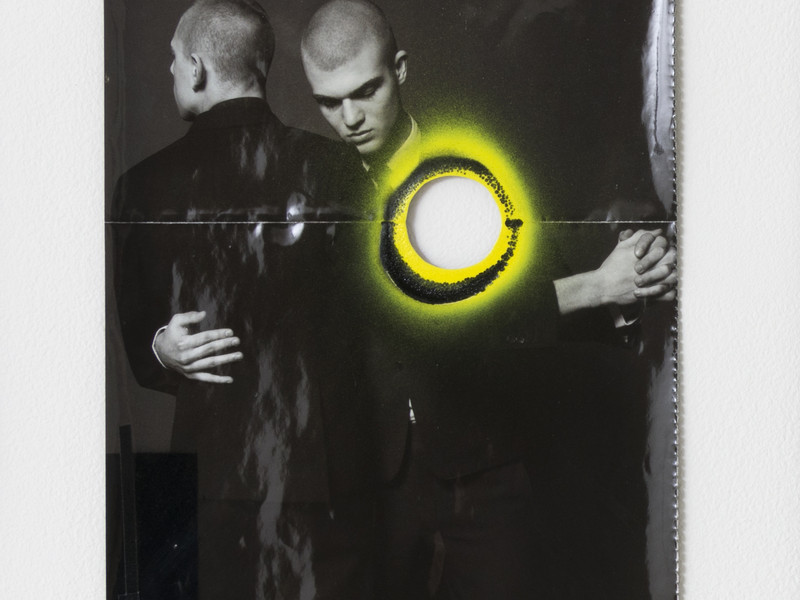

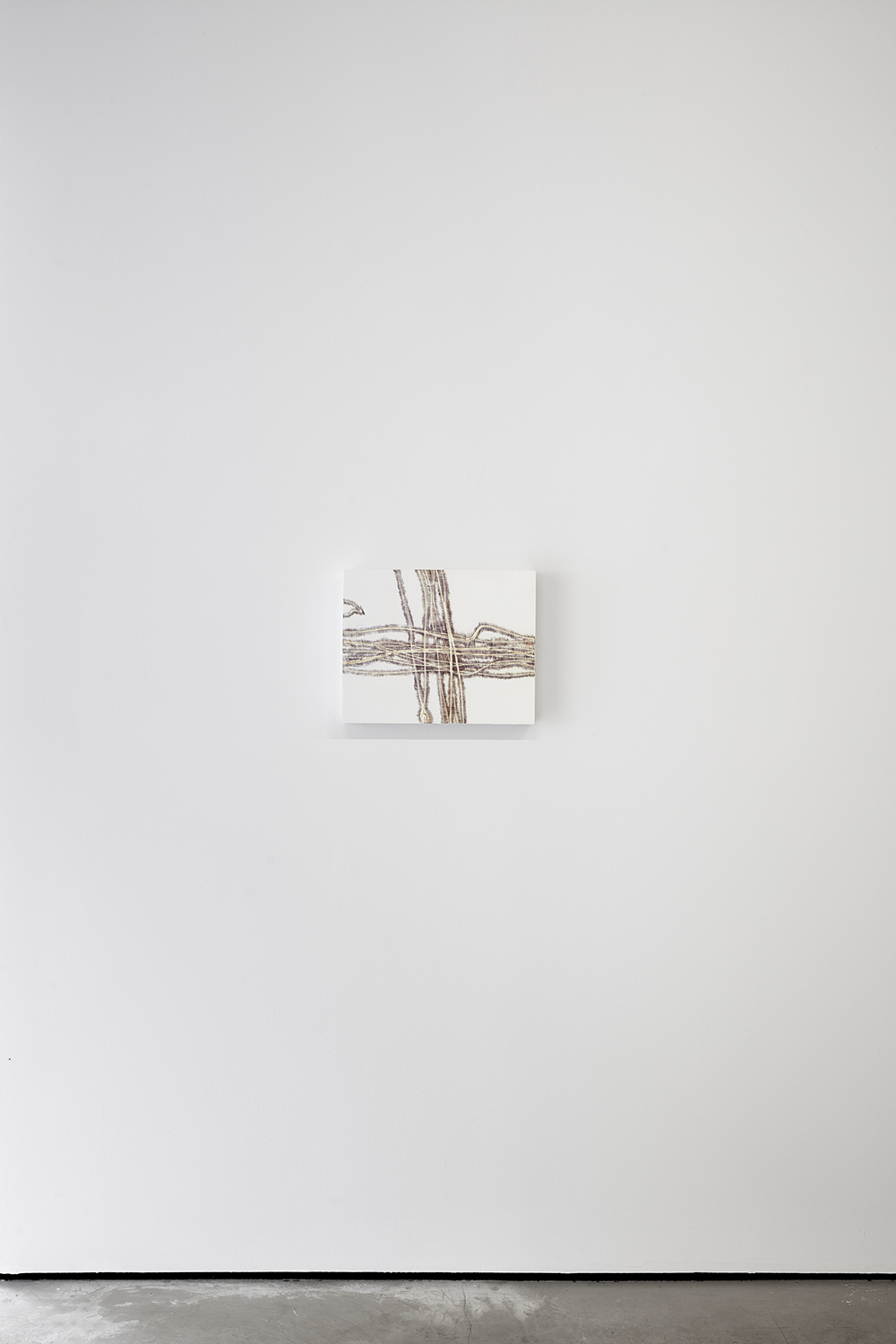

The compositions are rooted in details, clues to where she has been and perhaps a map to where she is going. While their subject matter is indiscernible, they nevertheless “manage to relate to the viewer,” she says. “There is something common in them and in the way I reproduce them.” At first glance, it is unclear whether some of Nguyen Quoc’s works are printed images. Their flattish surfaces don't give much in the way of texture as paint often does. But upon closer inspection (which, Nguyen Quoc writes on Instagram, is recommended to view at “8 centimeters distance,”) alternate hypotheses on their constructions arise. Are they hand-drawn? The level of laborious precision is almost absurd.

Nguyen Quoc works mainly with humble materials — the show’s standout piece, also called Offering Body and Soul to A Radical Alterity, is a hand-drawn triptych made by using countless Bic ballpoint pens. To create the piece, Nguyen Quoc thrust herself onto the lifesize wood panel, surrendering herself to the work, and repeatedly drawing arcs that reflect the degree to which her arm was able to move back and forth. Imagining the petite, eloquent artist working herself both mentally and physically to her limits is truly awe-inspiring. As she speaks, a jumble of conceptual theory, anthropological terminology and scientific knowledge comes out in eloquent, well-phrased composition. Her paintings, similar to her way of speaking, dance between that exacting precision and free-flowing conception. Below, we caught up at her new show.

First off, can you tell me what grounds your practice? Is there a cohesive thematic element to your work?

Since the start of my practice, what has caught me and created a desire to inscribe something is what I call “leftovers.” That is to say, it made these traces that were not wanted, but in a clandestine way [are] a witness to the existence of life that were not represented. This remainder of something is not an object, nor a fragment, because we don't know what it is. It is something without body, which therefore has no iconographic language already inscribed.

Can you talk about the title of your show — Offering Body and Soul to A Radical Alterity? Were you influenced by Jean Baudrillard’s seminal text, “Radical Alterity”?

When I come face to face with a trace of an image that calls to me strongly enough to make me want to transcribe it, I will observe it and set up a whole protocol, like a ritual. I'll look for a gesture and techniques that will correspond to what I perceive. For me, the safest way to maintain a relationship with the world is not to interpret it, but to look at it factually and physically without ascribing particular meanings to things. In this position of copyist, I have to withdraw from myself to suppress my affect and fascination for the image. This is the only way that I can both understand the meaning of the image and also to encounter radical otherness — something that's absolutely not me. I think it is in this encounter with what's not us, that we can make the constitutive experience of humanity, that of coming up against plurality and differences without affixing our own desires to a thing.

What was your process for making the works for this show?

For this exhibition, I worked with the residues that my production and reproduction work had left around me. [For Drawing to Gathering Stars, these were], the patterns that emerge in the ink tubes of my empty ballpoint pens to the bottom of the ceramic cup in which I prepare my colors. It's the trace that I left when I produced other images. While making the color for that work, the pigment had left a thin film at the bottom of the cup, and I wanted to clean it by rubbing it lightly with a tissue. And when I lifted [it], this image appeared. I thought it looked like an image of a galaxy or an atom and its electrons. So we were going from the macro to the microscopic, and I had the feeling it was saying a lot about my work — at least the relationship we can have with it. I've been told that from far away it looked like a printed image. And once you get closer to the surface, it's like a whole world traced by mechanical hand. I think my work asks for this back and forth — moving away and then coming back to [it]. Because what we seem to see from far away is nothing.

Your process seems quite methodical and meticulous — there’s almost a scientific nature to it.

This is the most accurate way to translate the image without changing it. My images are sometimes outside the language of words. I'm often asked what they are. It's not that the question is not of interest, it's just that people see what they see. It's beyond my control. It solely depends on each person's lived experience. We can't necessarily put words on what we see. We can look at how it is done.

You clearly read and write a lot. How does language show up in your work?

There is a form of writing that is not made up of letters and words that can be read — humanity has always [done so]. We were reading the stars and coffee grounds and birds flying before language built and ordered the word. My work uses a more archaic language, the way we read the world around us, or the way we know that a river once flowed in what is now a dry riverbed. My gestures are mechanical, but a human action is never really mechanical. It's not just a matter of execution. Every technical action that I undertake is articulated by my sensation. The technical differences in my work are not stylistic effects, I simply have to adapt to the different iconography of my images.

Where would you say your influences come from artistically, or theoretically? Are there certain texts you refer back to?

Most of my influences are anthropological. My teacher, Dominique Figarella [at Beaux-Arts de Paris], is the one who told me, ‘you have to understand what techniques mean in your work.’ He advised me to read Marcel Mauss, who is the father of anthropology, and then I read Deleuze.

And how does that show up in your work?

The way in which [my works] are produced technically recalls ways of doing, psyches and lifestyle habits. [They] take on the human condition — the repetition and how we build our life and our psyches. They are not necessarily artistic gestures — they recall the gestures of an office worker or even a student at his desk copying something. Modernity pointed out that techniques participate in the experience of perception, and the question of language preexisted the distribution of signifiers.

What do you seek to get from your work? Or what is your relationship to it?

I wanted to understand the relationship with the viewer, because it's the only thing that puts me in relation with the world. I really wanted to be able to communicate and to understand why people are interested in my work.

In the press release for your show, it says that “if the thing seems to have potential for inscription, the potential to be a signal, then she works on it.” How do you know when there’s a “signal,” and the image you want to create?

I don't know, because my practice is not that domesticated. I think it's a good thing because I don't want to have to handle my work so tightly. I think this is why I draw things, because I try to understand the meaning of the image and why it was so strong to me. I had no choice but to make it. What I think will make me a good artist or not is to find the right images that will signal to people. Every trace can be a signal, because it is a trace of an activity. Homo sapiens evolved by reading the traces left in other spaces. We survived because we are able to read the traces in the world.

Your piece, Offering Body and Soul to A Radical Alterity is really incredible. It’s a giant triptych made from the humblest tool — a Bic ballpoint pen. Can you describe what your process for making it is like?

I trace [the lines] with many ballpoint pens. The size [of the strokes is] the size of the movement allowed by my arm. I discover my images only at the end. I put myself on it and I trace for hours. We can really know where my body was at the moment when I trace these.

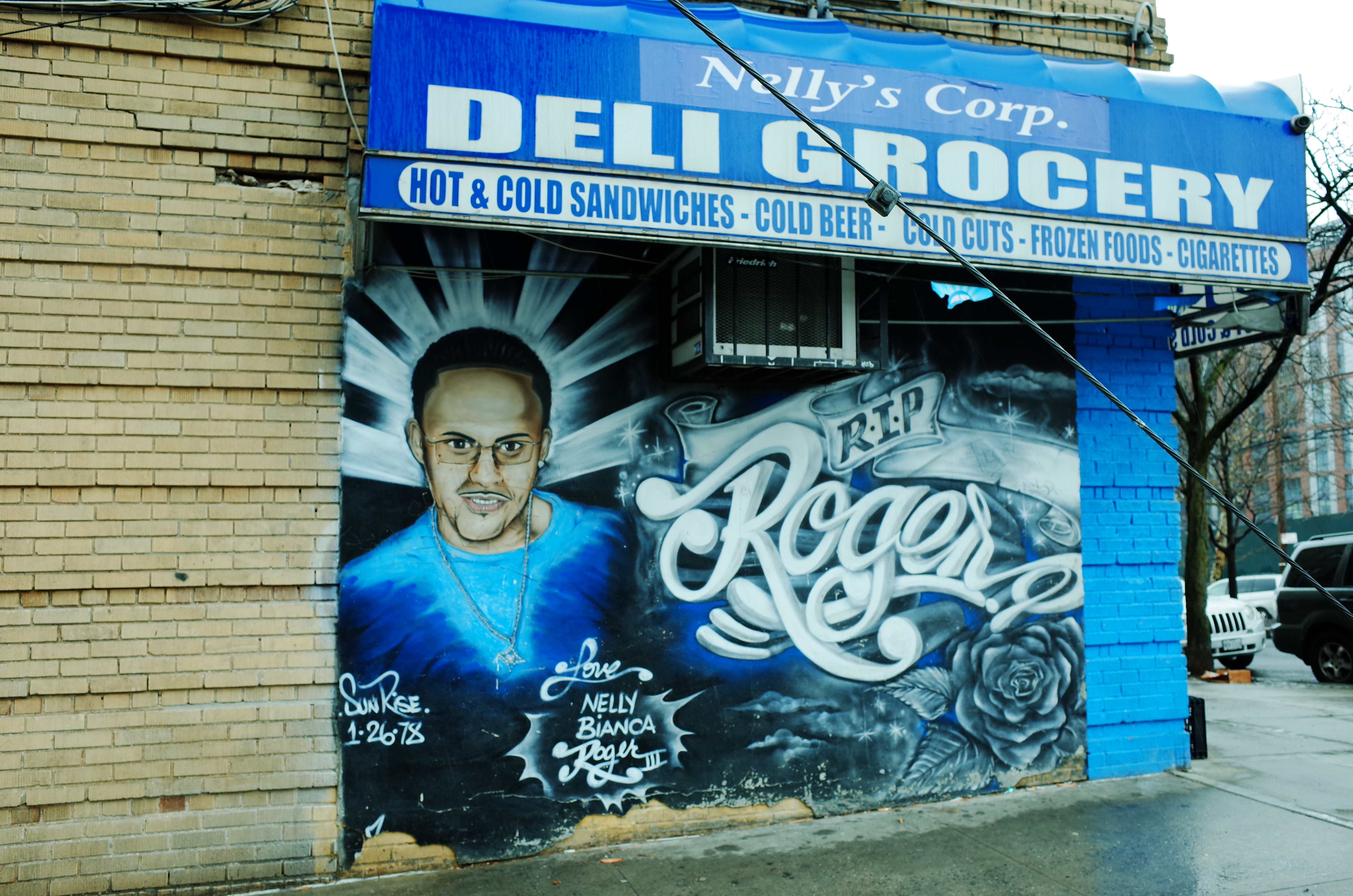

What was the source material or image that it’s based on?

The image is a photo that I shot in school. It was a window ceiling covered in dust. Birds were falling on it, and their wings were scratching the dust. Light was coming through. This is an exact copy of the image. So this is not abstraction. It's a copy of what I saw — traces of birds who were falling because the window ceiling is not straight.

There's an element of masochism in the way you make art. You push yourself so far to create the image, it’s about seeing how far the work can go.

It's painful for sure. I'm getting a personal trainer who prevents injuries because I’m worried for my body. I work 12 to 15 hours a day. During my master’s degree, I came to the studio at 8 o’clock and I was leaving a bit before 9PM. So for that kind of work, I have kind of an urgency. I can't stop — I need to fulfill everything. The only thing that stopped me is my body. My work asks for time. If I want to produce a certain amount, I need to work a lot.

Offering Body and Soul to A Radical Alterity is on view at Gratin gallery until June 7 2024.