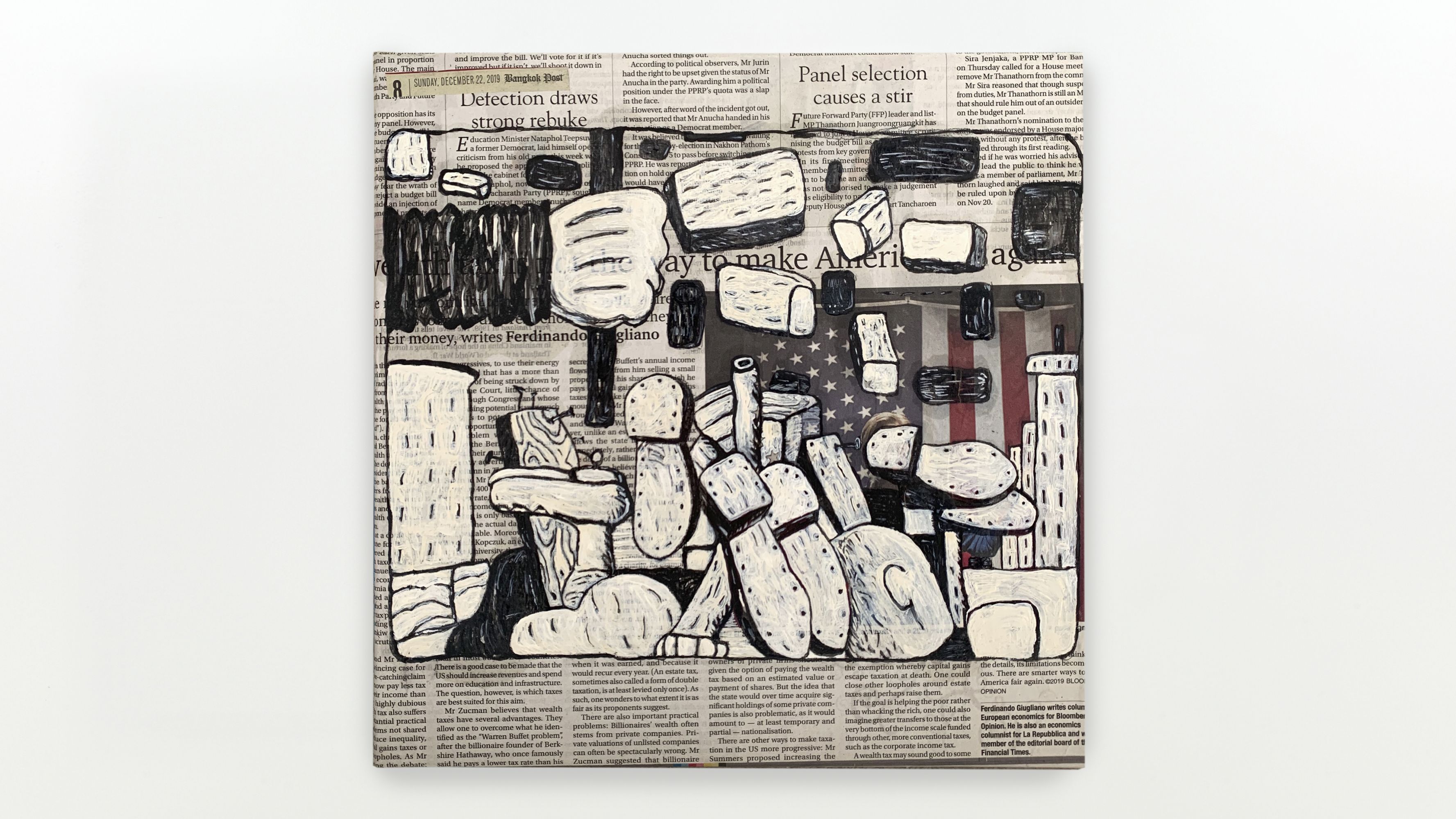

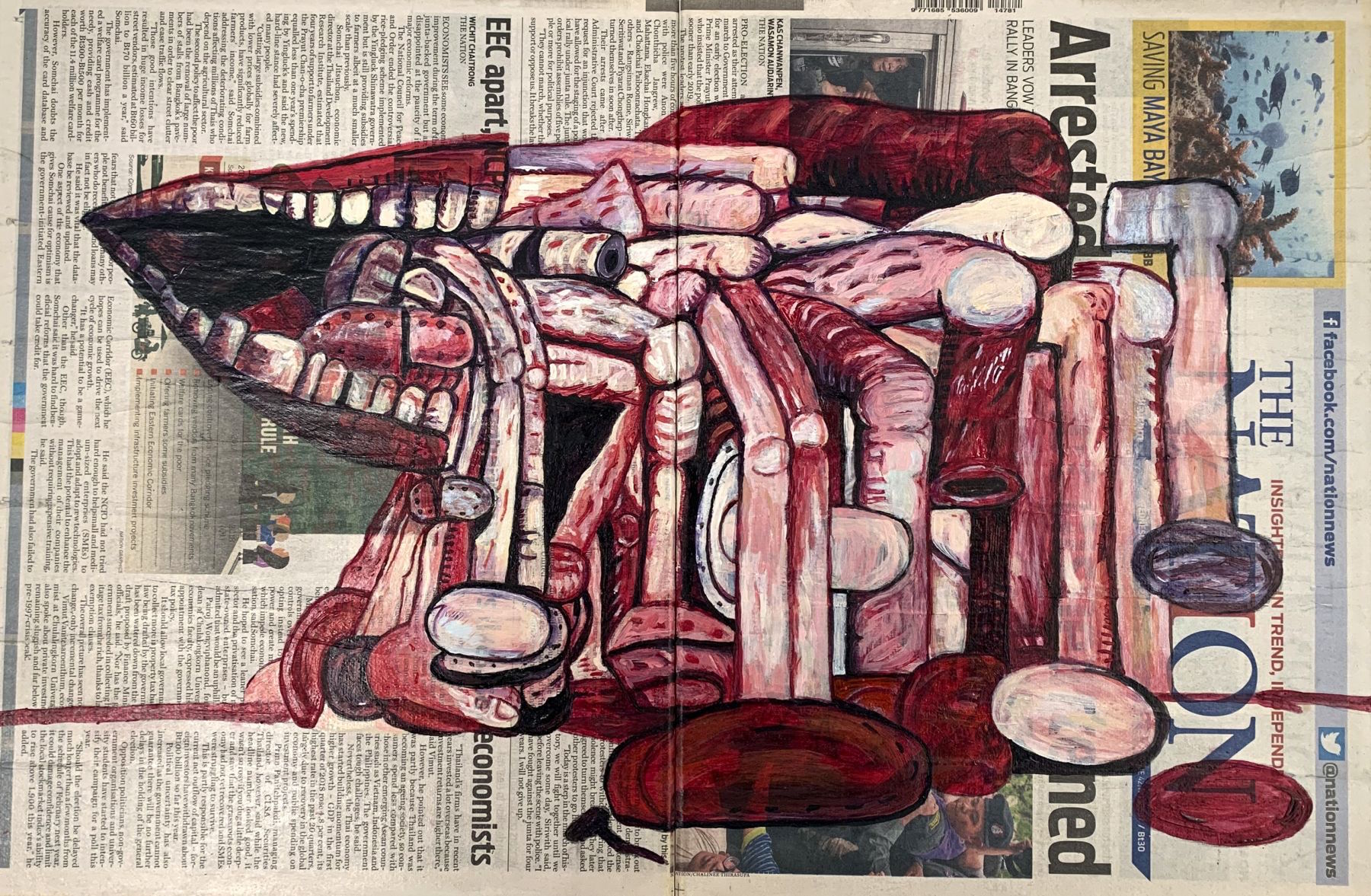

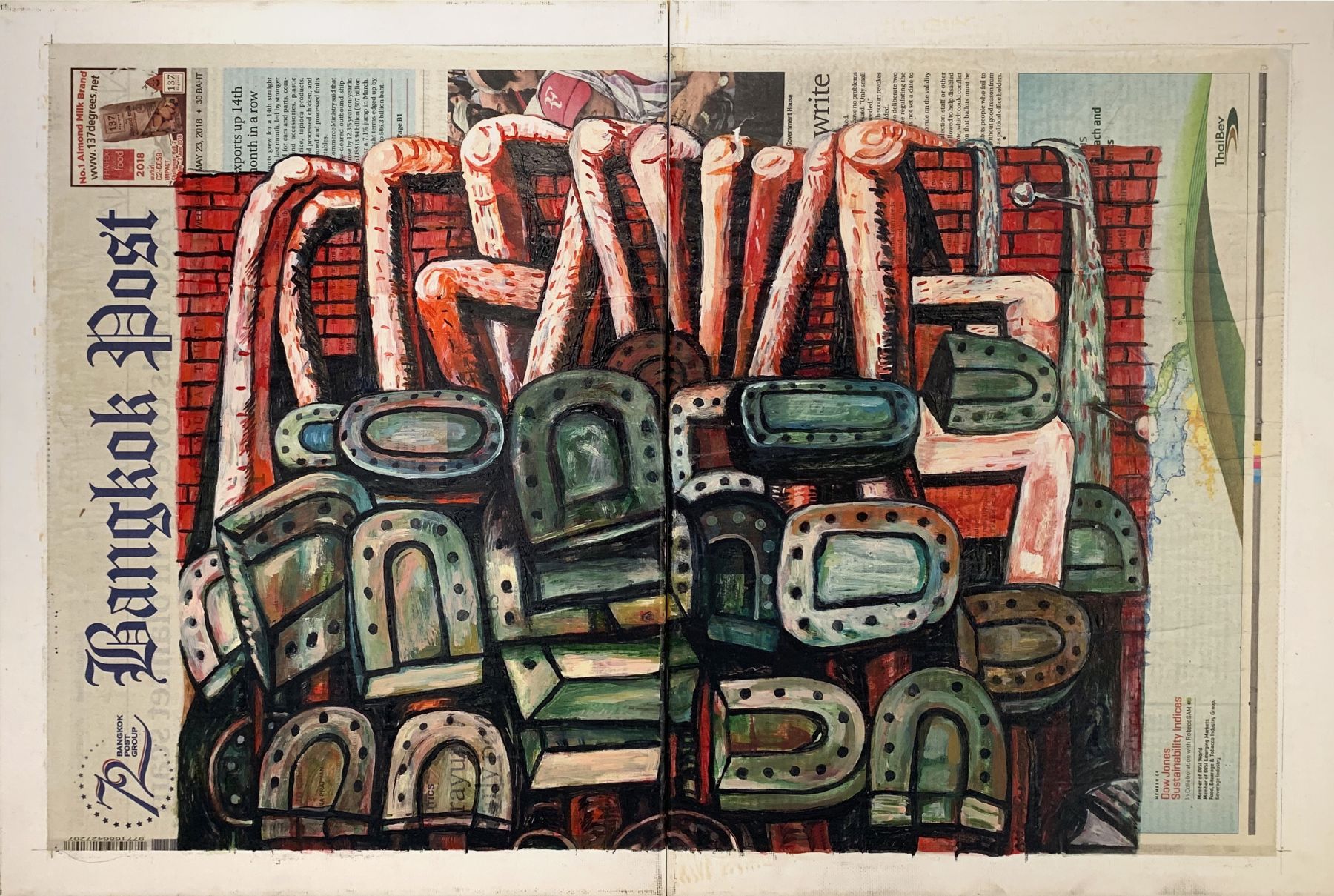

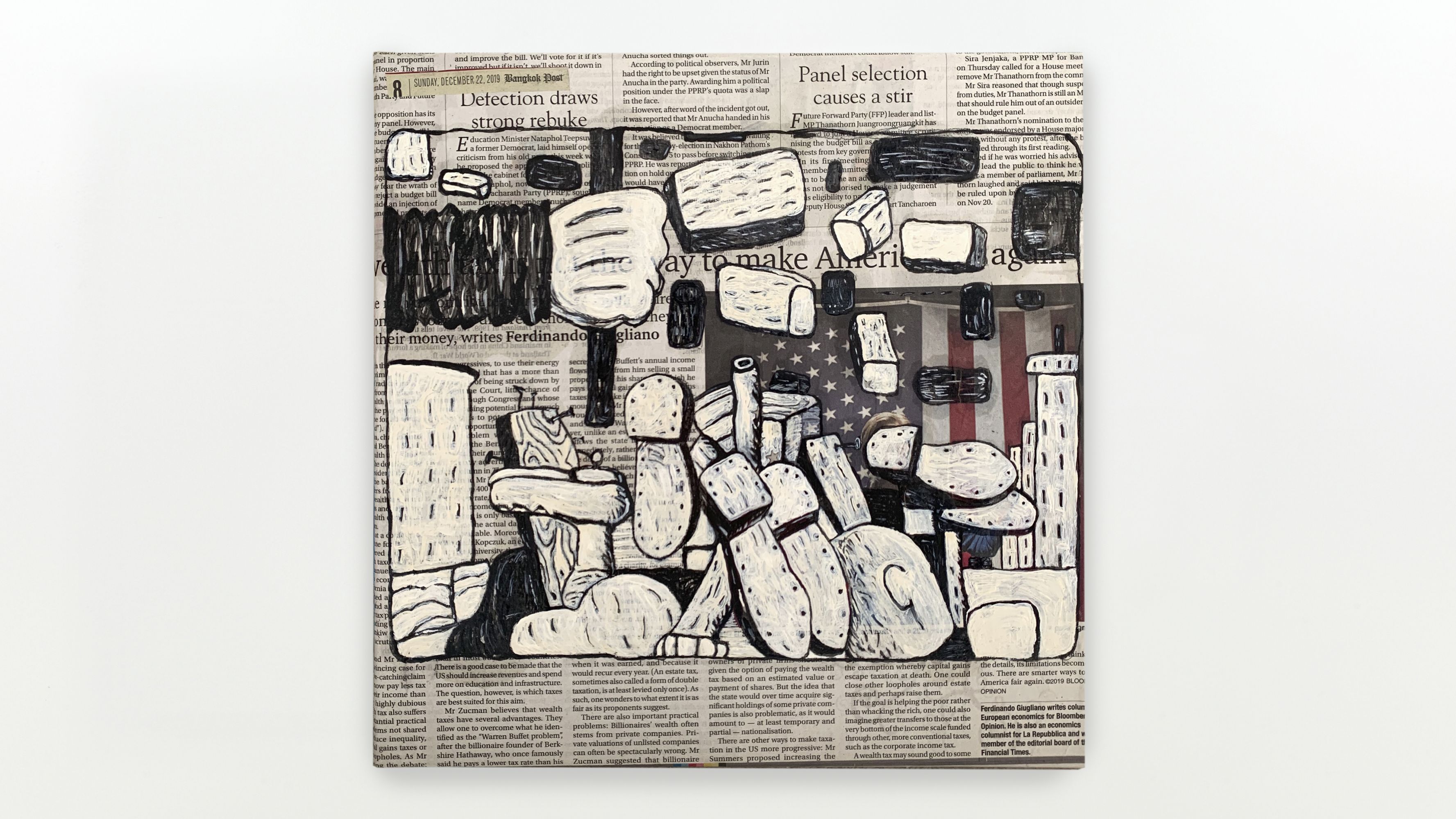

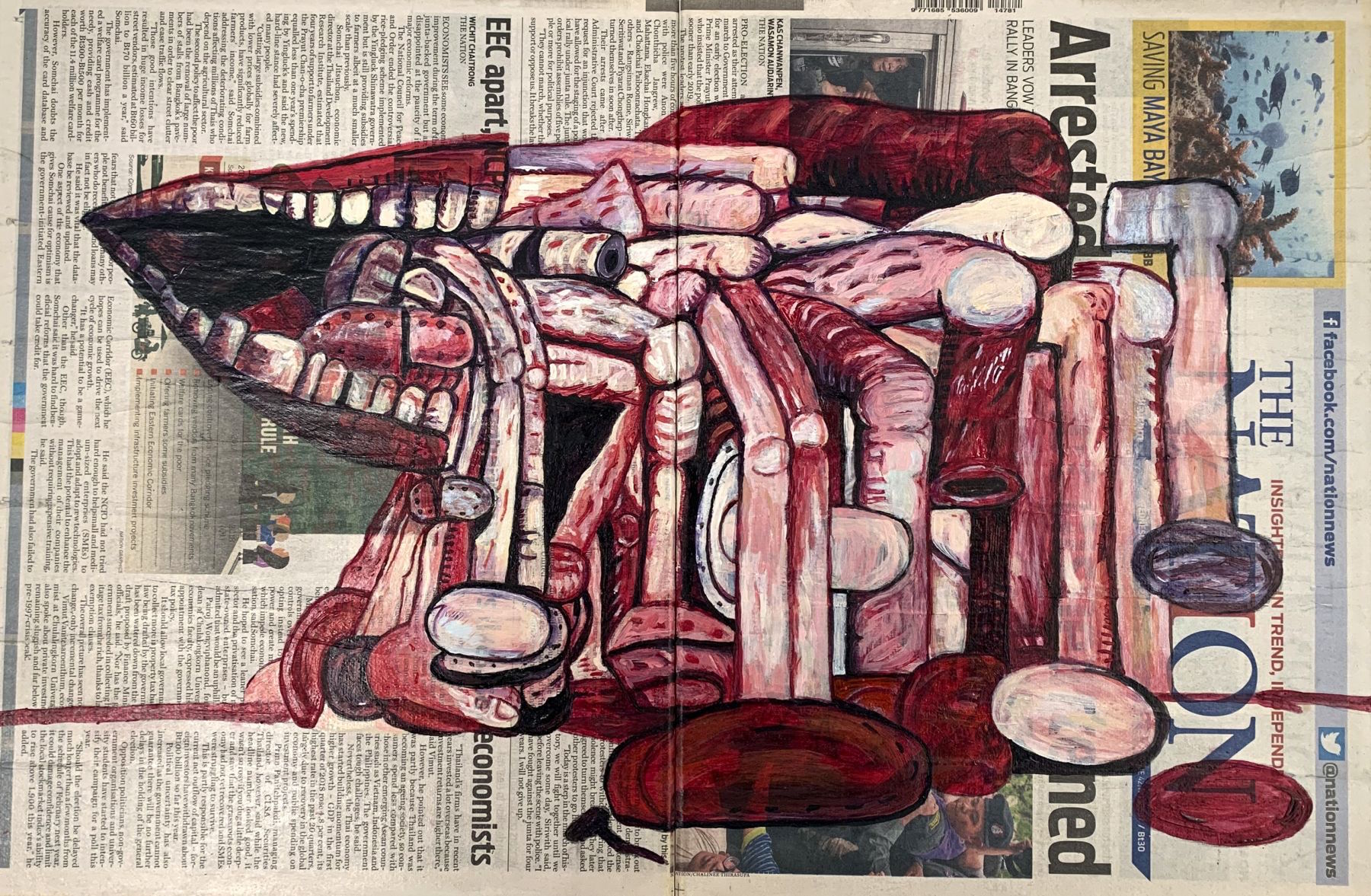

Opaque News

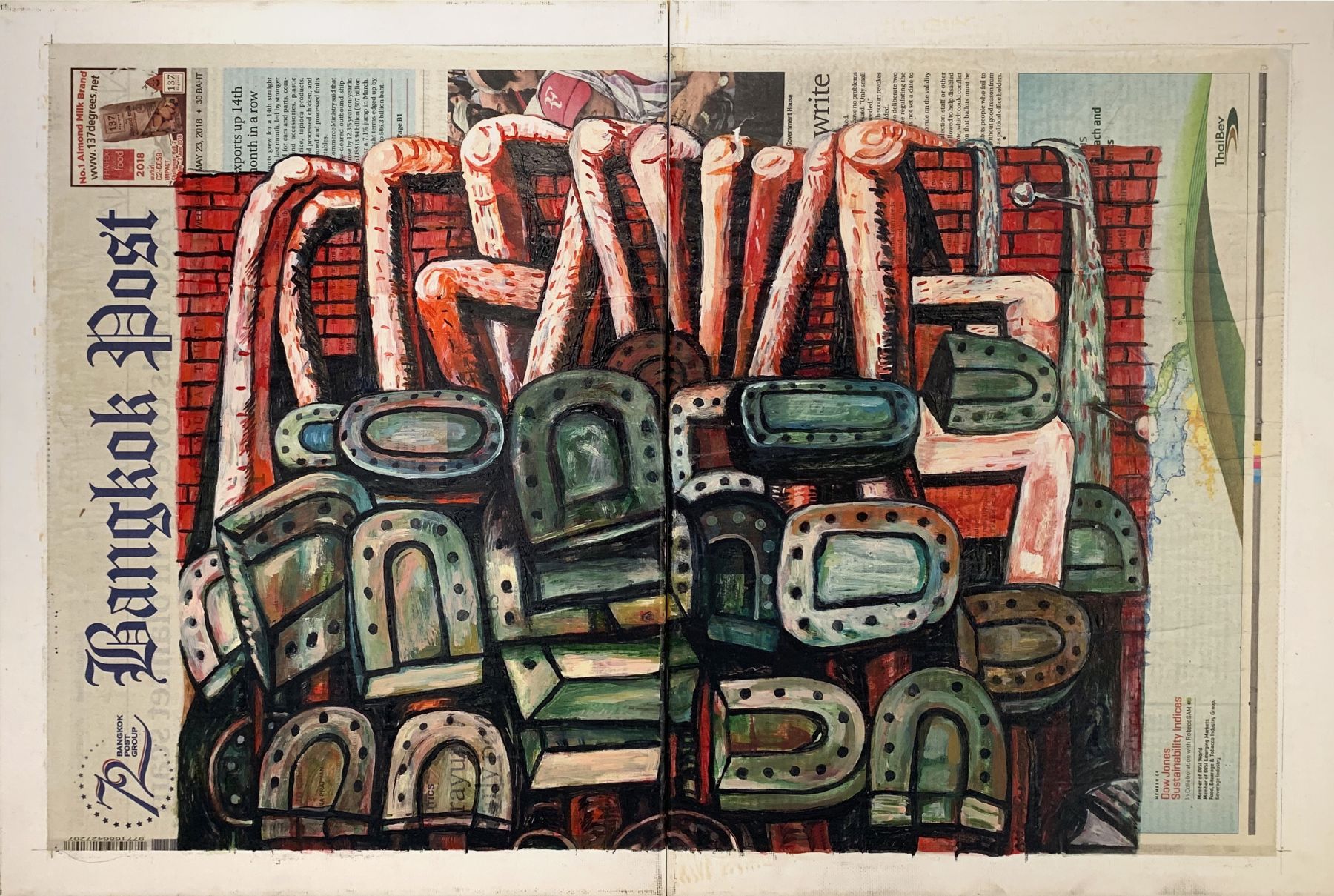

Lead image: untitled 2020 (Green Rug, 1976) 2020 Acrylic and newspaper on linen 11 7/8 x 15 3/4 in.

Check out more featured artworks below.

Stay informed on our latest news!

Lead image: untitled 2020 (Green Rug, 1976) 2020 Acrylic and newspaper on linen 11 7/8 x 15 3/4 in.

Check out more featured artworks below.

There’s a playful provocation that runs through the book. When asked if he’s slept with everyone featured, Knepper laughs: “No comment. I’ve done some damage, but not everyone.” That energy — part confession, part myth-making — pulses throughout the pages. It’s a document of queer life without moral boundaries, but not without heart.

More than anything, Sidepiece is about visibility. “I wish I saw something like this when I was younger,” Knepper says. “This isn’t about labels. It’s just about being a young New Yorker, breaking some rules, figuring it out with your friends, and living with no apologies.”

In a culture that still urges people to hide their mess, Knepper offers a tender middle finger. Sidepiece doesn't glamorize destruction — it simply acknowledges that the path to becoming yourself is rarely neat. And sometimes, the sidepiece is the real story.

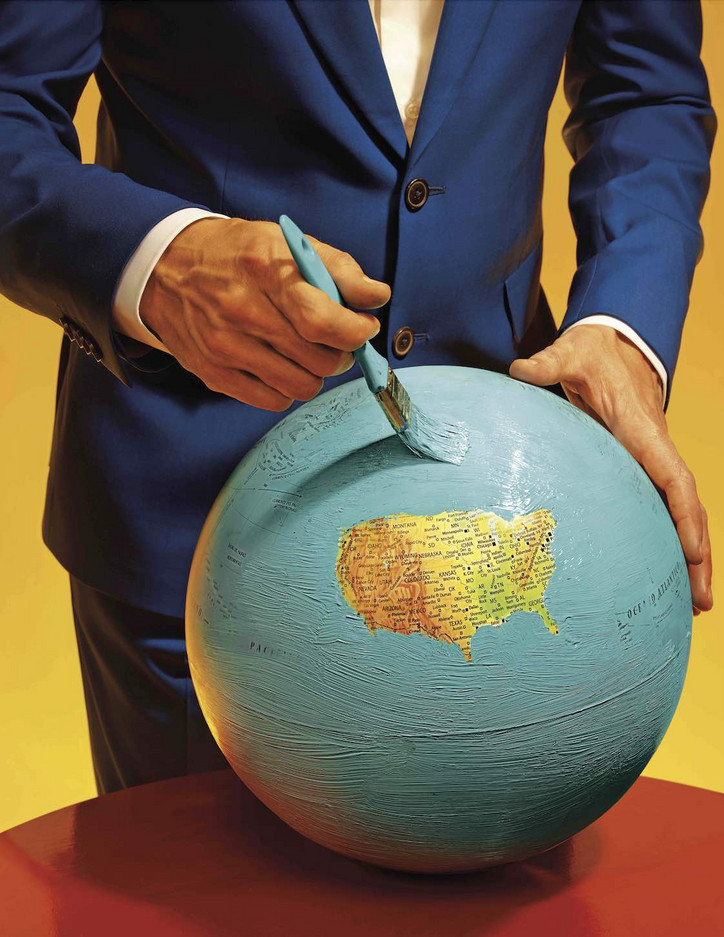

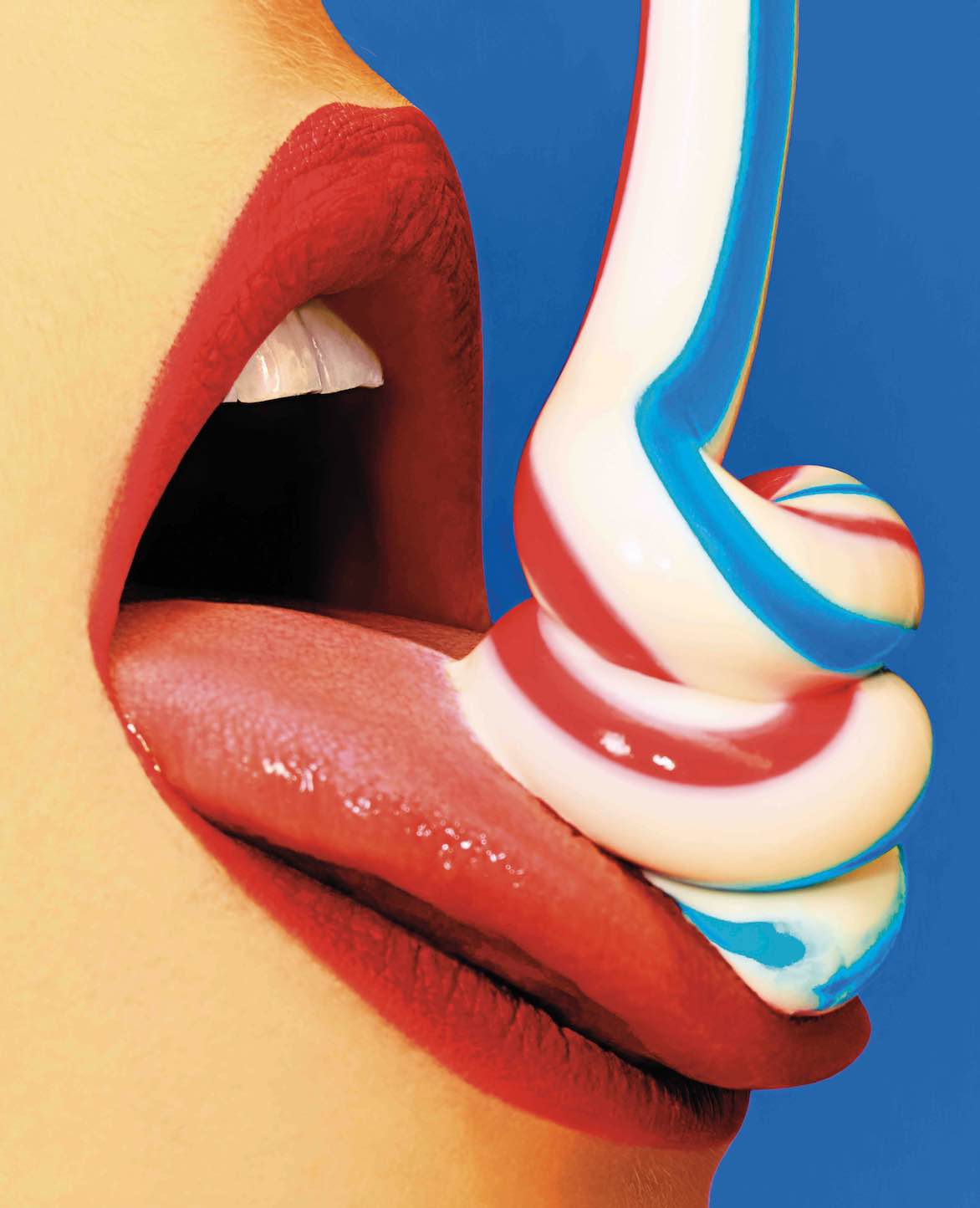

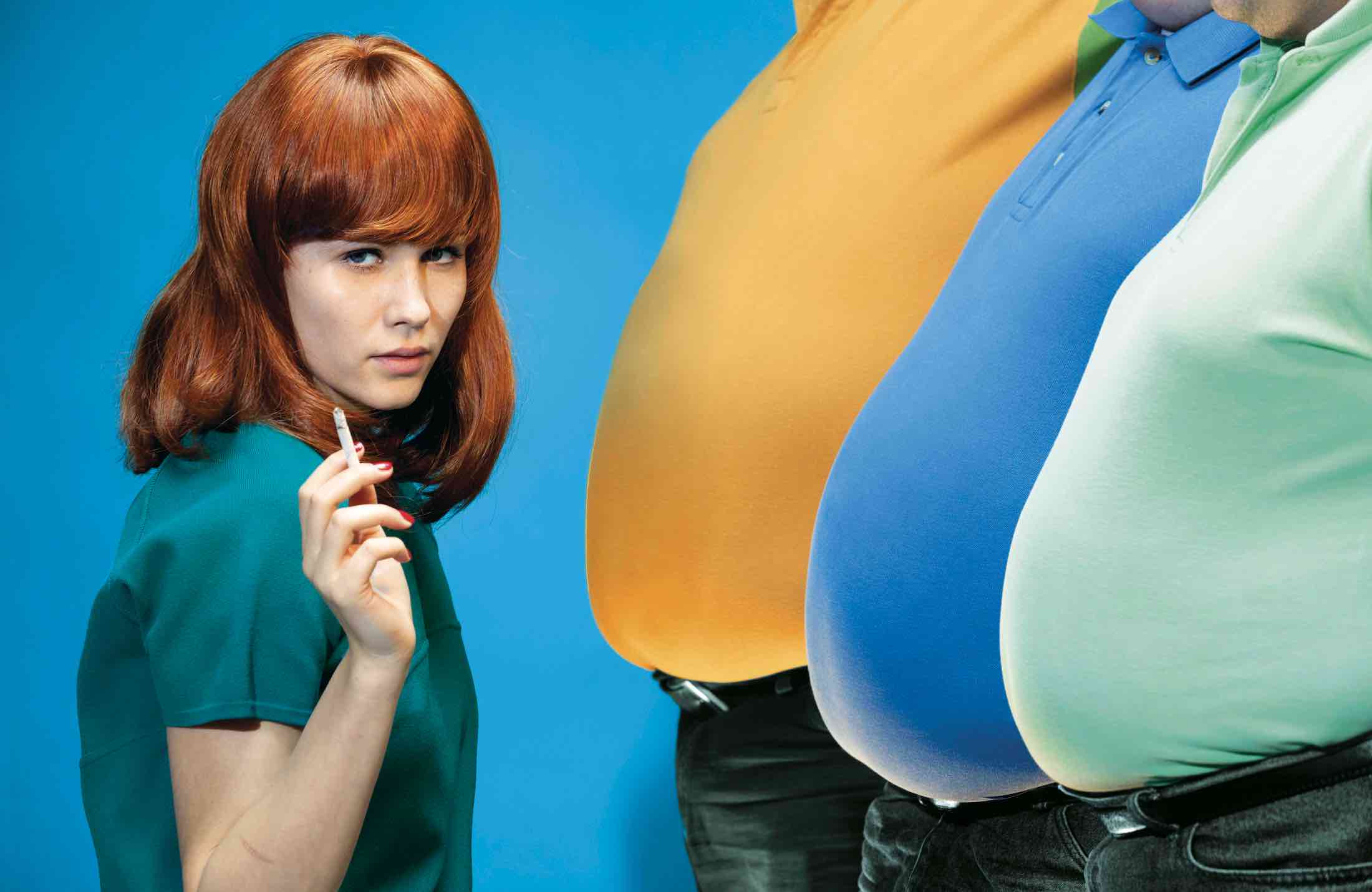

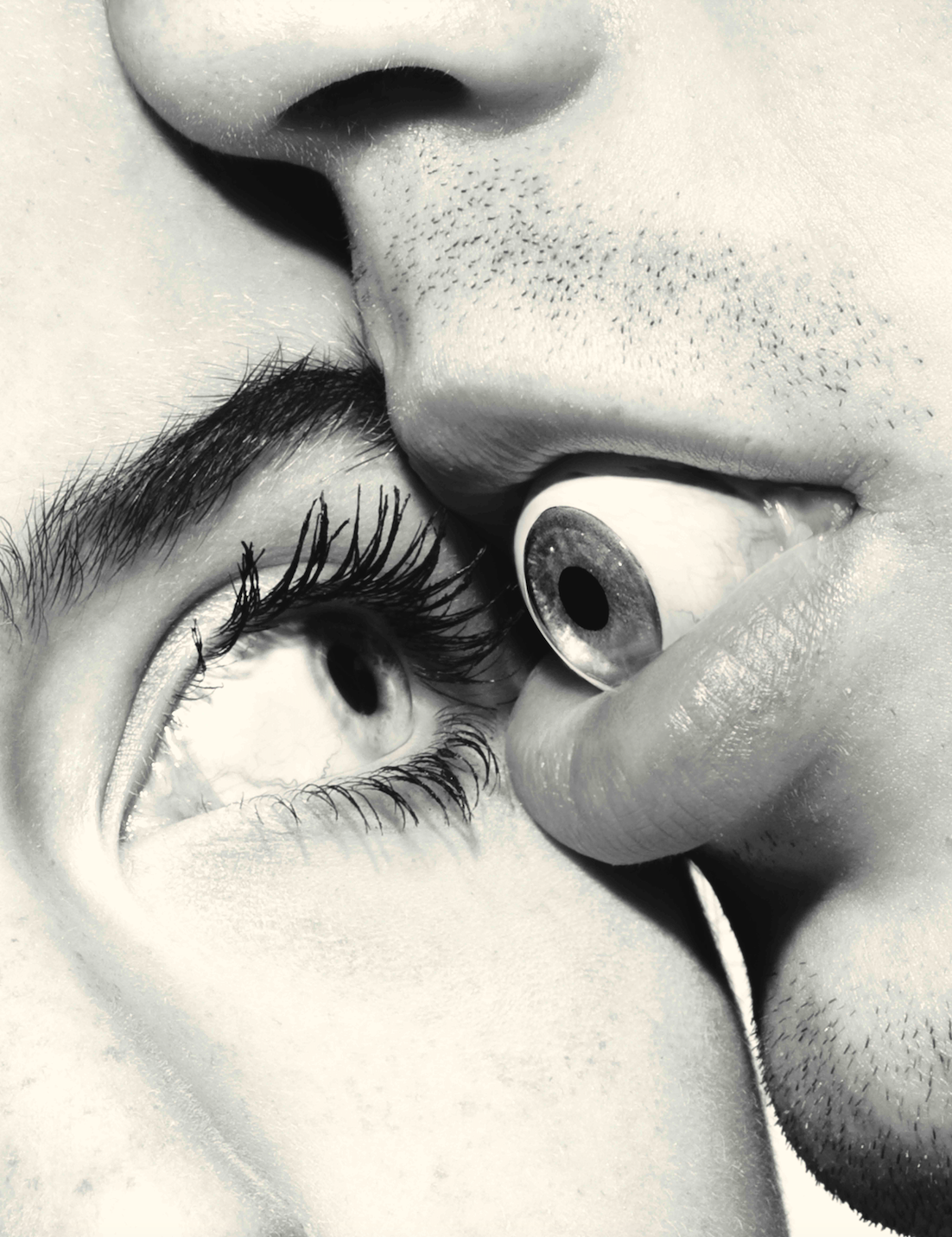

Now, that visual universe explodes into three dimensions with ToiletFotoPaperGrafiska, the duo’s first major Berlin exhibition, open at Fotografiska Berlin through August 2025. Think magazine spreads brought to life: immersive, disorienting, surreal, and sexy. "It’s like being invited to the best party of your life, where everyone is wildly intoxicated and you’re the only sober person in the room," Maurizio and Pierpaolo said. Visitors are pulled into a world of pool-sized banana pits, garish visual riddles, and worlds that defy logic and resist explanation.

After years of letting their images do the talking, office finally got a few words out of Maurizio and Pierpaolo.

TOILETPAPER feels like a high-gloss fever dream. Where did the original idea come from?

It came from a very specific need: we didn’t want to talk anymore—we just wanted to scream through images. TOILETPAPER was born as a silent manifesto with the volume all the way up. A way to say everything, even the opposite, without ever really explaining ourselves.

How did you come up with the name?

We wanted something essential, universal, and a bit annoying. Everyone uses toilet paper. Every day. It's democratic and we liked the idea that the images could be torn up, used, and thrown away. Like certain thoughts you just can't flush out of your head.

What makes an image a “TOILETPAPER” image?

Is there a rulebook or just a shared gut feeling between you two? If it makes you laugh and provokes a little, then it works. When an image is both disturbing and desirable, then it’s TOILETPAPER. But above all, if it sparks a debate—if it raises more questions than it answers—then it hits the mark.

Do you think that your experience in commercial photography has influenced the imagery you choose?

Of course. It’s like using the enemy’s weapon against them. Advertising teaches you how to seduce— we use that seduction to take you to places you never meant to go.

If TOILETPAPER had a smell, what would it be?

Spaghetti al pomodoro.

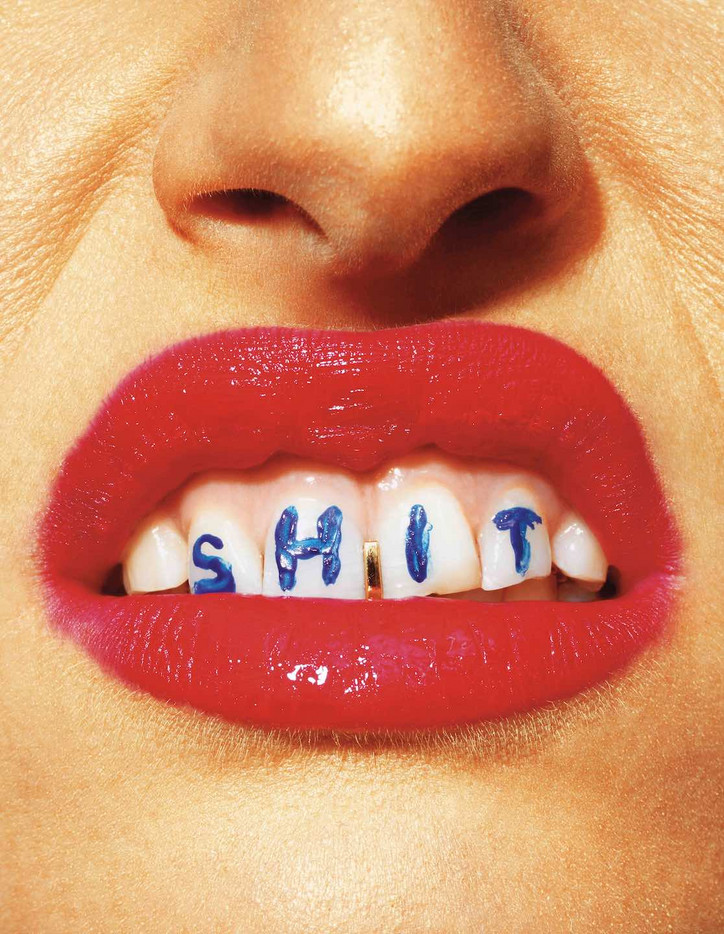

So much of your work delicately balances discomfort—chopped-up fingers, lipstick on teeth, raw meat. What role does disgust play in the visual language of TOILETPAPER?

"Unease is a trigger. When you can’t look away, even though part of you wants to, it works. It’s that feeling of ‘I wasn’t ready to see this—but now it’s burned into my brain.’" questa come risposta?

Your images walk the line between attraction and repulsion, humor and horror. How do you know when you’ve found the right balance?

If it doesn’t make you a little uncomfortable, then it’s not TOILETPAPER yet. The perfect line is where you start laughing—and immediately wonder if you should feel ashamed.

Has there been an image that made you laugh out loud?

All the pictures with animals always put me in a good mood. For example the one about the polyamory of cats hugging each other.

If the world ended tomorrow, and someone found a copy of TOILETPAPER buried in the rubble—what would you want them to understand about humans?

We disappeared because we took everything too seriously, and nothing seriously enough. And yet, we tried to be funny—sinking with style in a bathtub full of rubber ducks.

What is the last thing in each of your search histories?

“How to escape an interview gracefully”.

What’s the weirdest thing in your trash cans right now?

Our youths.

What’s your ideal office?

On a beach in Costa Rica.

Do you travel on tour?

We worked very closely with Shakira and the creative team for nine months to a year and got it to the first show which took place in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. After that, we communicate with the team and see how things are going but we only took it to the first show. There's a whole production team that then looks after the entire production and design on the road.

Right, so you laid the blueprint for the design for the rest of the tour. What was the initial vision for the design and how did you come to collaborate with Shakira?

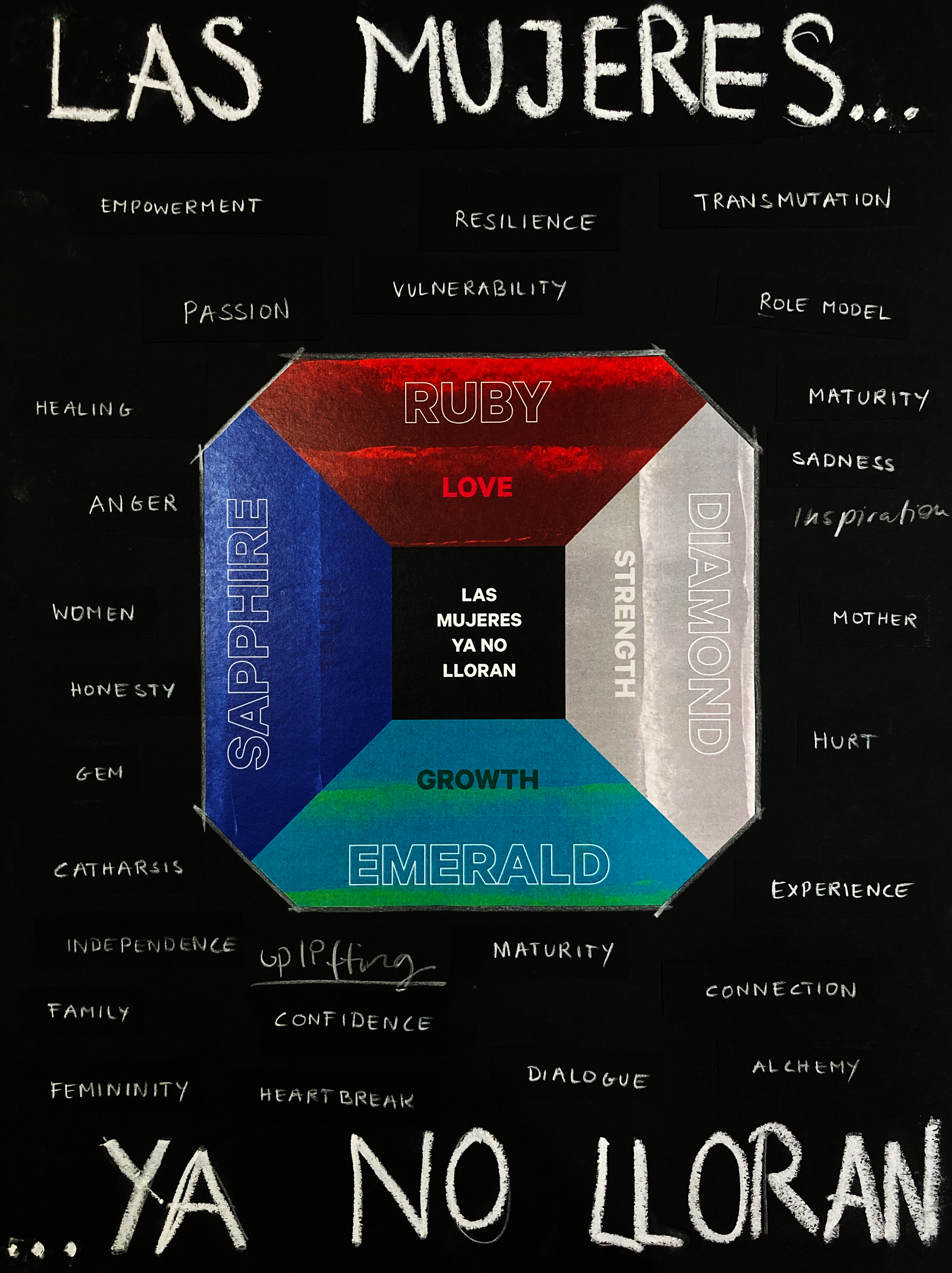

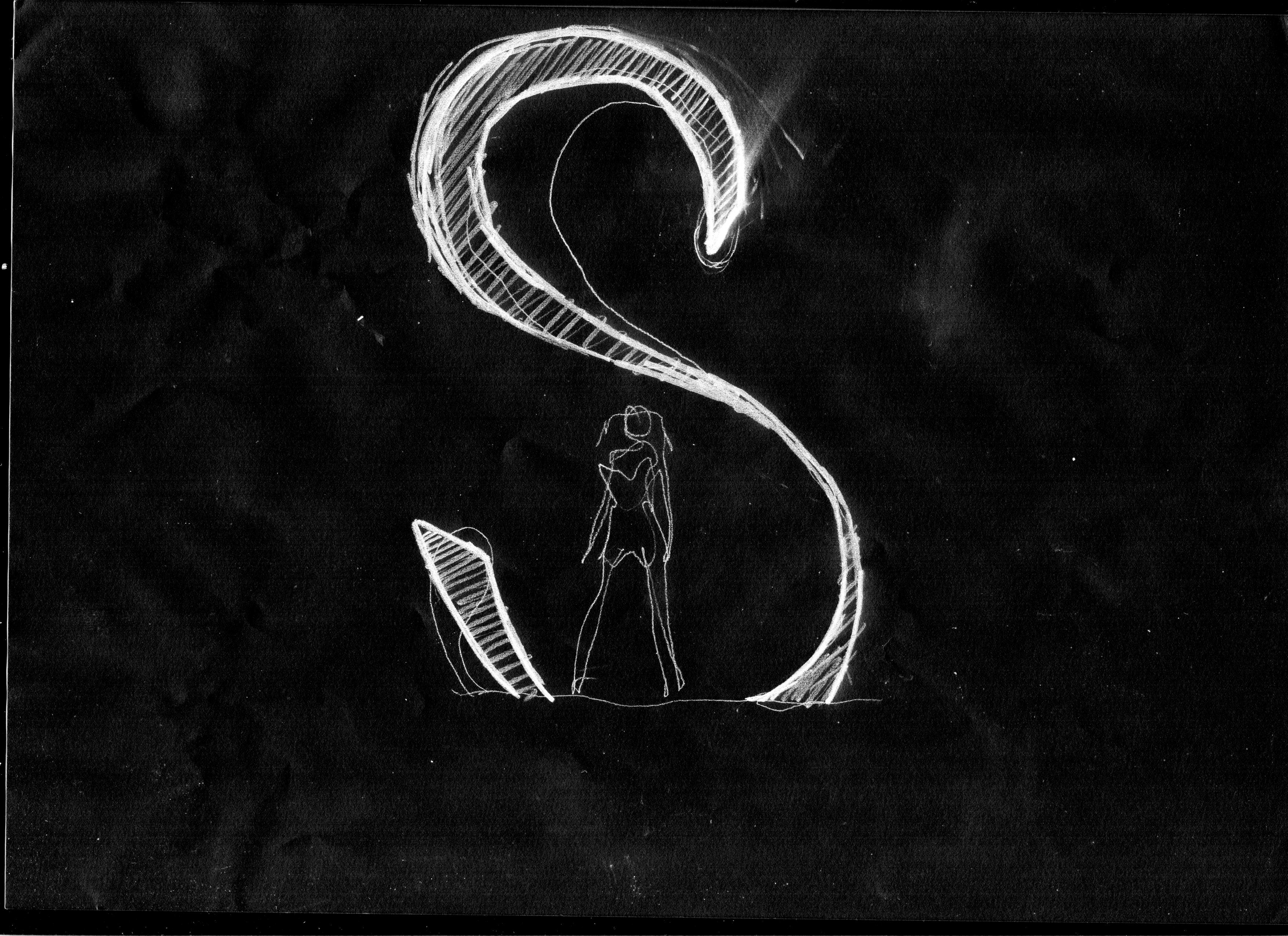

When we got approached to be creative partners and designers for the tour, Shakira had just released a new album [Las Mujeres Ya No Lloran] which was the first one in seven or eight years. It was a big deal for her to release it and start creating this tour which so far, has been the biggest tour of her career now that it's on the road. It's quite incredible. Like everything else that we approach, there's always a script, an order of a show, or a bible, right? If you're doing an opera, you have a libretto. If you're doing a play, you have a script. So in a way, when doing a tour, the music was our bible. The music was our script.

We listened to the album with Damun [Jawanrudi], the lead designer for the show many, many times. That gave us a good structure as we started to understand the meaning of the songs and began researching and drawing inspirations based on the concept of her album. We then met several times in Miami with Shakira and our creative directors from THE SQUARED DIVISION to start the whole design process. We all met around the table several times to workshop ideas and discuss the look, feel, and pace of the show. It was a really wonderful collaborative process between all of us.

It’s so important to have good collaborators for a big production like this.

100%. We love collaborations and even though we are production designers we like to think that everybody earns the design. Shakira and the lighting team, we all work very closely together so we all should feel just as proud of what we achieve.

Completely. How did you bring in some of the themes in the album like empowerment and vulnerability? In what ways did that influence the design choices you made?

There are some very specific moments that we created that reflect on the topics of women’s empowerment and resilience and there are some that are more suggestive through video content. For example, there is one particular moment in the show where Shakira comes up on a hydraulic elevator. She rises out of a mountain of diamonds (wearing a dress which is also made out of diamonds) so it looks like she's coming out of the Earth. That represented the resilience of diamonds themselves as they are essentially a rock that can survive over millions and millions of years to create this beautiful end product. It was a metaphor for the woman that Shakira wanted to portray. Someone who is a survivor, resilient, and strong. Coming out of the darkness and of the Earth in order to bring prosperity, joy, and empowerment. That was a wonderful and specific way we portrayed those themes.

That's beautiful. I'm excited to see that.

Yeah, it's a wonderful moment because it’s a huge spectacle we’ve created around stadiums and arenas and even if you are sitting in the first row or the back of the stadium Shakira manages to make it feel very intimate. She has songs that are more acapella, for example, but then also has full-blown production moments that reach out into the entire audience so that sort of level of intimacy is really there. Even if you're sitting at the back you can see the beautiful quiet moments. Her voice is so powerful and so recognizable so it's a wonderful sort of way to bring those moments and scale them up and down.

Was it a challenge to bring that sense of intimacy when you're designing for such huge stadiums and arenas?

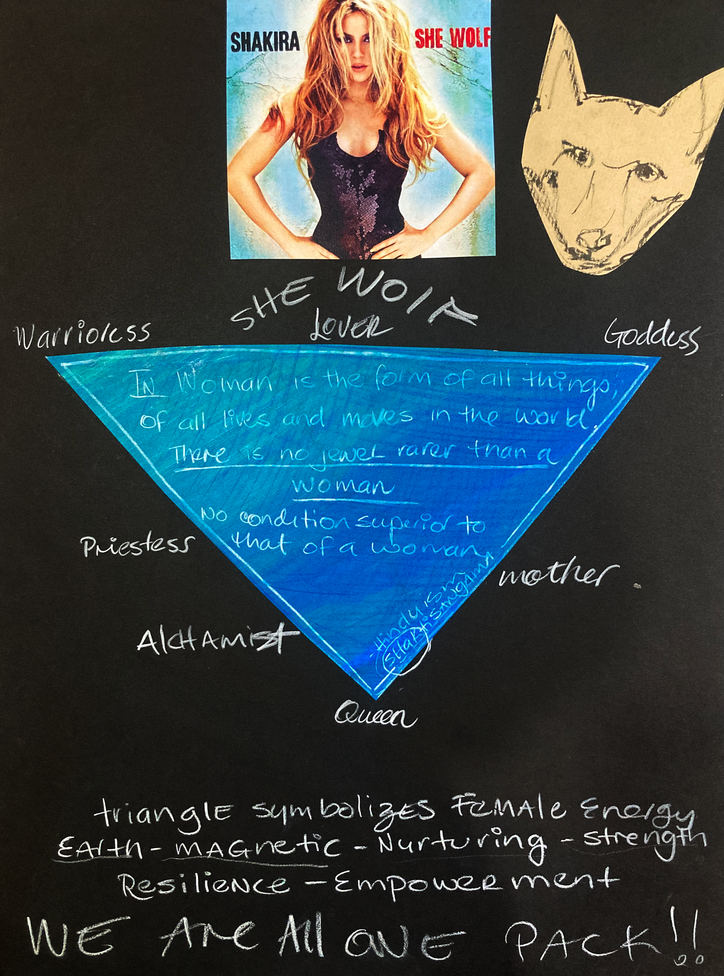

Everybody has a glow bracelet which has been around for a while, but it's a trick that works. Shakira’s fans are the Wolfpack and so the light on your wrist is a really powerful way for you to be connected to the community of wolves and to feel the intimate moments that might be happening on stage. That’s just one example and it worked really wonderfully in scale.

Is there anything that you explored in this project that you've never explored before?

We've done a lot of interesting reveals through technology. One of the challenges of being on tour is that there are a lot of unknown factors that might affect the design like the weather. The design is made up of a giant screen that connects down to the floor and becomes this huge monolithic catwalk. It's a very clean minimal approach, but within it we have a lot of technology that creates a playground for Shakira and her dancers.

We have hydraulic lifts that come up out of the catwalk on stage. We have the screen itself, which opens and closes through automation to reveal other elements of production. There's a lot of technical elements that we've done before but not necessarily on a tour of this scale. That was a big challenge to overcome creatively, bringing the logistics of the weather and being outside and so on. How do we make sure it runs smoothly? We have some of the best collaborators in the world helping us execute this.

And collaborating with Shakira on this, what did that mean to you? Were you a fan of her work before?

It does mean a lot to me. I am Australian culturally, but I am Latin and originally from El Salvador. So working with such an iconic artist like Shakira brought up a lot of unexpected emotions and it was a real honor and a pleasure to be working with the most iconic Latin artist in the world. It was wonderful to see how collaborative and professional she was. My team and I were very much about facilitating a creative landscape for her and she responded really well to what we brought. So I guess from a professional and cultural standpoint that meant a lot.

Even just speaking in Spanish because I speak Spanish and Damun, who led this project, also speaks Spanish. The three of us and some of the other people on her team, we were able to switch from English to Spanish in a very informal and easy way. Later on, when we opened the show in Rio, seeing that Latin culture come together was amazing. Being there to just admire this incredible fandom. The Wolfpack really does exist, especially in Latin America. We opened the show in Rio and then went to São Paulo. We had one hundred and twenty-five thousand people per show and it was incredible to see how much energy the fans had.

How do you hope that people feel after the show? What do you hope they leave with after experiencing this?

It's a celebration and a reminder of how powerful women can be. When you see it, you will see what I mean. What we all want, including Shakira, is that recognition of empowerment and that celebration of survival. We as humans, especially women, can survive and can get through the journey. It's a happy journey but there's also some serious topics there and the message is strong. We have found a way to tell the story of empowerment through elements like the wolf pack.