every cell met with instant ease

when i speak to myself i use the kindest language i can summon, i am allowed the same grace i give others

and once i gave myself permission i was radiant

Stay informed on our latest news!

when i speak to myself i use the kindest language i can summon, i am allowed the same grace i give others

and once i gave myself permission i was radiant

(Photo by Robin Hart Alexander)

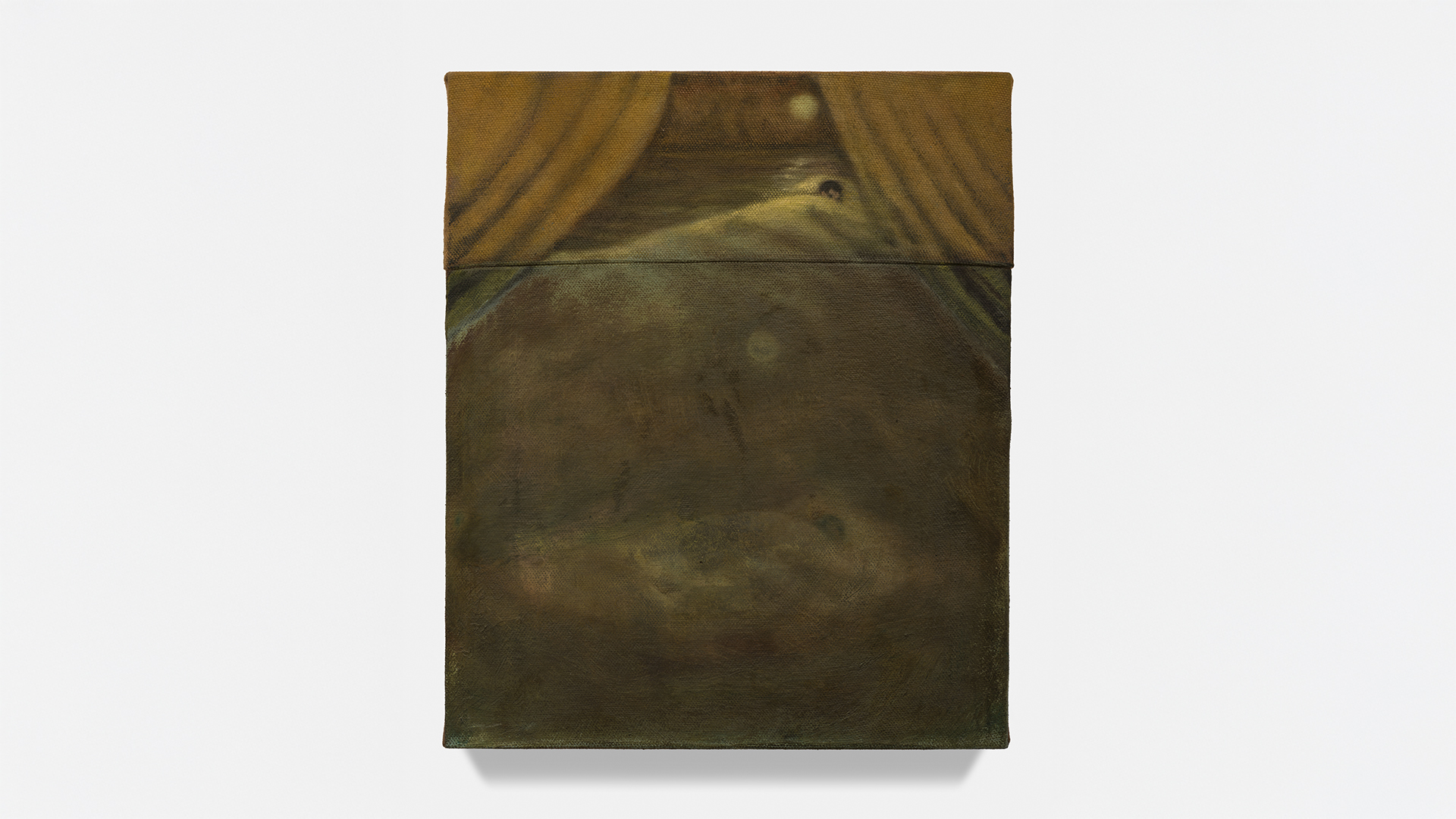

A self-taught painter, Schneiderman likes to embrace the spontaneous interplay of materials. “The dyes create a pattern or an idea that I can later dissect or intervene with a brush,” Schneiderman tells Office in a recent interview. Plant dyes, which he encountered while working in a Denver boutique, introduce an element of chance into the process. Images and ideas often germinate organically, as Schneiderman’s materials mirror his own physical and emotional landscapes.

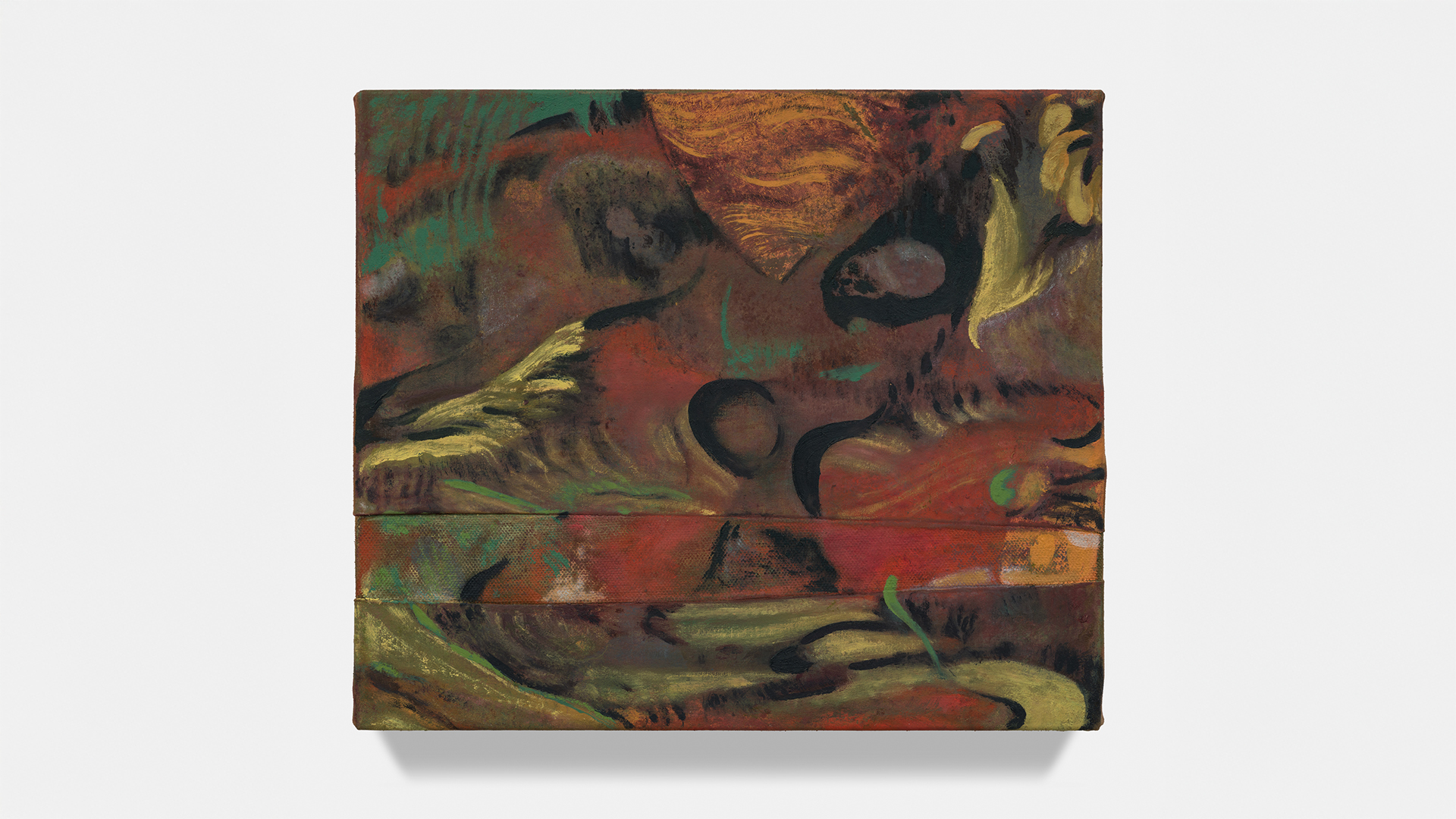

Contrary to the title’s implied minimalism, The Big Empty—a phrase borrowed from the country singer Coulter Wall—is activated by a potent kinetic charge. Some of the show’s paintings were made in a small Los Angeles garage before Schneiderman relocated to a larger space downtown. The frenetic energy reflects the cramped nature of the studio he was working in. Limited room and constant movement infused the pieces with urgency and tension, as if the paintings were pushing against walls.

“I like to lay out all the paintings in my studio and see how they vibrate, how they talk to each other,” Schneiderman says. He prefers working on multiple pieces at a time to capture this emanating dialogue. His canvases are linked by a subconscious symbiosis, a quality that has attracted viewers seeking a harmonious connectivity with art. During the pandemic, Schneiderman’s work swiftly gained an online following; his paintings serve as portals into a shared space of introspection.

“A feedback loop starts to occur, and I start to notice how one painting might influence or inform another, ” the artist adds. Familiar shapes and patterns—concentric circles, opaque nebulae, and flexuous earthworm-like squiggles—recur across the canvases, contributing to a visual ecosystem fueled by a cross-pollination of ideas. Each painting is its own ethereal landscape of ecstatic forms, evoking cosmic explosions (How the Heart Unfolds), desert storms (Playing the Bones), lightning sprites (Visitor Map), and molecular fusion (Dweller on the Threshold). Schneiderman also had David Lynch’s catchphrase “Catching the big fish” in mind while painting The Miraculous Draft of Fishes, inspired by the director’s idea of meditation as a means to deeper creative expression.

The large-scale canvases reflect a conceptual evolution for the artist, who has more recently shown in Italy and Switzerland. “Abstraction has always been a destination I’d wanted to arrive at,” Schneiderman says, “but I had to chisel away at my instinct to make references to get there.” There is an apparitional quality to a work like The Magician, which alludes to a figure hidden from view. Remnants of these specters haunt the canvases—a fishing net, a disembodied ear, a snow-covered forest—but Schneiderman’s interest lies beyond the recognizable. His works are imbued with a latent spirituality that bridges the ecological and the transcendental.

“I think about ‘the big empty’ as this location or headspace, a kind of collective unconsciousness, where ideas exist and are exchanged,” he says. The painter, then, is like a medium, divining vibrant, imaginative visions from plant matter and pigment.

You said you first started painting at like 35. Do you remember why you started? What was it that led to you first picking up a brush?

I started painting because life, in all its twists and turns, finally pushed me toward it. I think it had been waiting for me all along. There wasn’t some grand epiphany — more like a quiet, persistent whisper that I had ignored for too long. One day, I just listened. My ex-girlfriend handed me a brush, I picked it up, and at that moment, it felt like I had been holding it my whole life without realizing it.

Did you instantly think, ‘Oh shit, I’m good’, or was there a big learning curve?

Oh, I definitely didn’t think I was a prodigy right out the gate. But I felt something — like I had found a language that had been buried in me. The technique, the discipline, those came with time. But the feeling? That was instant. It was like discovering a door I never knew existed and realizing that on the other side was every piece of myself I had ever lost.

How did you look at painting when you first started? Was it like a hobby, a spiritual or mental release? Or was it a serious career choice?

At first, it was survival. Not in the financial sense, but in the sense that I needed it to feel alive. It was a return to myself, a place where my mind could breathe. I didn’t think about careers or collectors or exhibits. I just thought about what it meant to create something that felt honest.

It sounds like your life before painting was totally different from what you're doing now. Do you think the things you were doing then shape your work now? Or does it feel like two very separate lives?

They are the same life. Everything I was before is still in my work — it just took on a different form. The lessons, the struggles, the joys — they all seep into the canvas whether I plan for it or not. I think life always finds a way to speak, even if you change the language.

You have a series of paintings titled, ‘Loverboy'. Who is Loverboy? Tell me about him.

Loverboy is an echo of every love I’ve known, every love I’ve lost, and every love I’m still learning to understand. He is tender but reckless, hopeful but bruised. He wears his heart on his sleeve even when he knows it might get torn. He is me, and he is you. He is anyone who has ever loved with their whole being, even when it hurt.

If you were a color, what color would you be?

I’d be the color of dusk — the deep blues, the fleeting pinks, the quiet purples. The in-between of day and night, when the world is both ending and beginning.

What about if you were a medium?

If I were a medium, I’d be water. Something that moves, adapts, carves its own way over time. Something that can be both soft and unstoppable.

Where or when do you feel most creative?

When the world is quiet, and I can hear my own thoughts without interruption. Sometimes that’s late at night, sometimes it’s in the middle of a crowded street when I see something that sparks something in me. Creativity isn’t a scheduled guest — it arrives when it pleases, and I just try to be ready for it.

I’m curious about you designing all of your own clothes and jewelry. When and why did that start?

It started the same way all of my art does — with a need to see something that didn’t exist yet. I wanted to wear something that felt like me, like my paintings, like my poetry. I wanted to carry my art not just on canvas but on my body. So I started making things. And once you start, it’s hard to stop.

You also create sculptures, poems, and probably a lot more that I’m not aware of. Where do you think this need to create comes from?

From the need to translate life. Some people write it down in journals, some people sing it. I paint it, sculpt it, stitch it into fabric, shape it into words. It’s all the same thing — just different ways of making sense of the world and my place in it.

Before you get to painting, you always start with a poem. How does that transform from words to a physical piece?

The poem is the seed. The painting is what grows from it. I write until I reach a feeling that can’t be contained in words alone, and then I move to the canvas. The two aren’t separate — they are just different parts of the same conversation.

What emotions do your paintings evoke in yourself?

It depends on the piece. Some paintings are like exhaling — relief, release. Some are like a wound — raw, exposing. But all of them feel like truth. And truth, no matter how it looks, always feels like home.

What do you think, or hope, they evoke in your audience?

Whatever they need to feel. I never want to dictate that. If a piece makes someone feel seen, that’s enough. If it stirs something they can’t name, that’s enough too. Art is a mirror — we all see what we need to see.

What are you manifesting right now?

More life, more love, more creation. The freedom to keep exploring, to keep making, to keep feeling. And for whatever is meant for me to find its way home.

What inspired your designs and the company?

Was there a gap that you felt needed to be filled? RTH was born from both industry experience and personal frustration. After spending over a decade in high-end, collectible furniture, I saw firsthand the barriers that made great design inaccessible—long lead times, high costs and the misconception that expensive always means better quality. As both a designer and a consumer, I wanted to challenge these norms and create a brand that blends designer-level aesthetics with a more approachable, ready-to-go philosophy. Beyond that, I wanted to accelerate the merging of fashion and furniture—two industries that have been slowly converging into a broader expression of personal style.

You mentioned a heavy “fashion influence.” How does that manifest in the designs?

I believe your home should be as expressive and effortless as the way you dress. In my view, furniture and clothing are the same thing. RTH takes direct inspiration from how fashion brands approach design, presentation and marketing. Like ready-to-wear collections, our furniture is conceptual and thoughtfully designed, yet more accessible. The way fashion brands play with materials, color and form is something we incorporate into our pieces—whether it’s a bold silhouette, an unexpected material combination or a finish that feels as perfect as a great outfit. We also think about seasonality and freshness, rotating designs and colorways to keep things evolving, much like in the fashion world.

Are there particular art movements, architectural styles, or fashion designers that influence your designs?

A mix of inspirations find their way into RTH’s pieces. Architecturally, I’m drawn to a wide variety of styles. I’m a life-long fan of Frank Lloyd Wright’s work, as well as other classic American architects. I also admire the works of modern masters with a completely different aesthetic, such as John Pawson or Vincent Van Duysen. In fashion, I’m inspired by brands that push boundaries while maintaining wearability—think Jacquemus and Jill Sander. We have a joke internally where if we're ever unsure about how to present something we say WWJD - of course referring to the one and only Jacquemus, not the historical figure.

How do you balance functionality with aesthetics in your designs?

For me, furniture should be both an everyday essential and an expressive object. While RTH pieces are designed with personality, we never sacrifice usability for our end customer. Every piece we create is meant to seamlessly fit into real spaces—our designs aren’t just for show, they’re made to be lived with and experienced. Material choice plays a big role in this balance; we select finishes and structures that are durable yet visually striking. The goal is to create pieces that enhance a space without overwhelming it.

Do you experiment with unconventional shapes or mixed materials in your designs?

Absolutely. A huge part of RTH’s identity is pushing beyond traditional forms and expectations. You’ll see that in our mirrors, which go beyond basic to become sculptural elements. I also love the idea of mixing materials in unexpected ways—chrome with oak, stone with metals. There’s an interplay between hard and soft, structured and fluid.

Are there any crazy designs that you want to try? (Whether it be shape, materials, etc.) And have there been ones that you’ve tried and haven’t worked?

I have an obsession with classic details in clothing like buttons, stitching and fabric. I'd love to produce a mirror that incorporates some of these details. One concept that didn’t quite work was a mirror design inspired by Loewe's Pixel collection from SS23. We tried to create a mirror in this same vein but the samples never produced the same effect as our sketches or renderings. That said, failed experiments are part of the process. Sometimes they lead to even better ideas.

Are there current interior design/furniture design trends you see currently? What do you think will be next?

Right now, there’s a return to naturals, metals and structure which is in stark move away from the wavy design that dominated the past few years. People want pieces that feel tactile, personal and crafted rather than overly polished. Looking ahead, I think we’ll see a bigger embrace of mixed materials and unexpected textures.

What's your favorite piece of furniture in your apartment and why?

It’s hard to choose, but I’d say my dining table, which I made myself. It was a scrappy, personal project—made from leftover travertine scraps seamed together with thin white oak strips. The way the materials came together, plus the story behind it, makes it special. It embodies the idea of making something beautiful out of what’s readily available, which is a principle I try to bring into all of my work.

What was your last google search?

Most definitely something to do with Milan. We're making our European debut with 3 different installations and events during design week in April. If you combed through how many times I've googled anything Milan related this month you'd think I was moving there.