Explorations of Infinity

ESCHER. The Exhibition and Experience will be on view at Industry City until February 3, 2019, in Brooklyn.

Stay informed on our latest news!

ESCHER. The Exhibition and Experience will be on view at Industry City until February 3, 2019, in Brooklyn.

And it is in fact the very idea of abstract interrelational experiences that comes to mind when strolling through the exhibits within the three separate rooms of Villa Clea. The Ritsch Sisters seem to have approached the architecture and interior of Villa Clea with precise playfulness, as becomes evident in the first room of the exhibition. Against the backdrop of a minimalist sound installation featuring the sounds of birds from New York and Vienna combined with occasional piano notes, we see photographs mounted on curved aluminum plates, which engage in a respectful dialogue with the space and the spectators. These sculptural photographs seamlessly blend into the organic monomaterial construction, which largely consists of light curtains, mirrors and aluminum furniture. As they either face or turn away from the viewers, they create a captivating interplay of proximity and distance, resulting in a wonderful ambivalent experience between concentration and spatial dispersion.

The second room shows a video installation titled Sound of an Egg Peeling, a symbolically charged exploration of human interdependence and connection. German-speaking viewers will likely notice the phonetic similarity between the English eye and the German Ei (egg). Might this be a meditation on natality and the Ritsch Sisters’ shared fascination with the seeing eye? In any case, eggs scattered throughout the room (sourced from a neighboring farm) create an immersive encounter, especially when visitors start peeling one of those eggs themselves.

In the third and final room, we find ourselves standing in front of a bed over which the largest photo print of the exhibition looms, titled Full moon she thought. It shows a woman with half-open eyes gazing at us from a potential delirium. Or is she annoyed that we disturbed her in her private bedroom? Those who don't fall into the bed at this point can turn over and enjoy getting their hands on the publication Together Apart by the Ritsch Sisters, which was published last year.

Immersive and fluid

For Villa Clea, Matteo Corbellini has used the remains of an old body shop to build a new architecture made of clay and concrete, while Allina (Alessandra Pelizzari Corbellini) designed the puristic and clear interior. Together, they have created an immersive and fluid space where they live, offer art residencies and aesthetic experiences, in a community centered around contemporary art.

When I hit up the artist that I’d followed for so long — and thought I knew — he was en route to the Italian countryside, where there’s no internet. We discussed his decision to delete his account, his recent show, and his plans for the future — that is, for when he returns.

To a lot of people on the internet, including me, you’re known as Maison Hefner. But you recently deleted the account that I and everyone else was following in order to go by your real name, Monty Richthofen. Tell me more about that.

Monty Richthofen— I first started using social media in 2015. At the time, I had just moved to London and started tattooing. My friend Joe Fox told me that I should get Instagram to promote my work. I wasn’t really into the idea of social media and didn’t have a smartphone, so I asked him to make me an account. I was living and tattooing out of a tiny attic but I thought it would be funny to have a username that implied something different. And that was the birth of me posting tattoos on a cracked version of Instagram on my Blackberry.

But I see “Maison Hefner” as a character from my twenties when I was traveling a lot and doing tattoos. COVID slowed things down and I began focusing on painting. Now, I'm confident in who I am and what I do as an artist. And as I've developed my practice, I’ve decided I want to show under my real name.

It felt important that I put an end to the persona and pull the plug. I feel that a lot of established people in hype-based industries have missed their chance to quit. They're in their 50s and still carrying on a persona that has little to do with their current reality.

That’s real. But I can imagine people wanting to hold onto that, especially if they feel like that’s the only reason that they’re relevant. How do you let that go?

Fuck it. I wanted to jump in the cold water and see who’s actually interested in my journey. Sometimes, just like a snake, we need to shed our skin in order to continue growing. I believe as an artist, it’s my duty to leave my comfort zone to challenge not only my own perspective but also the perspective, conventions and realities of others. As an artist, you are where you are in your career because you've done the work. By deleting a social media account you don’t lose the success nor the work nor the connections you’ve made. After all, Instagram is just a platform.

Did you hold any type of memorial for Maison?

I didn't want to make it a thing and just went dancing after I deleted the account. I had a really fun time dancing by myself, feeling the weight off my shoulders and realizing that I now have space and time for other things. It felt good to let go. The account gave me a lot of independence and stability but it was a burden at the same time.

R.I.P. Maison Hefner.

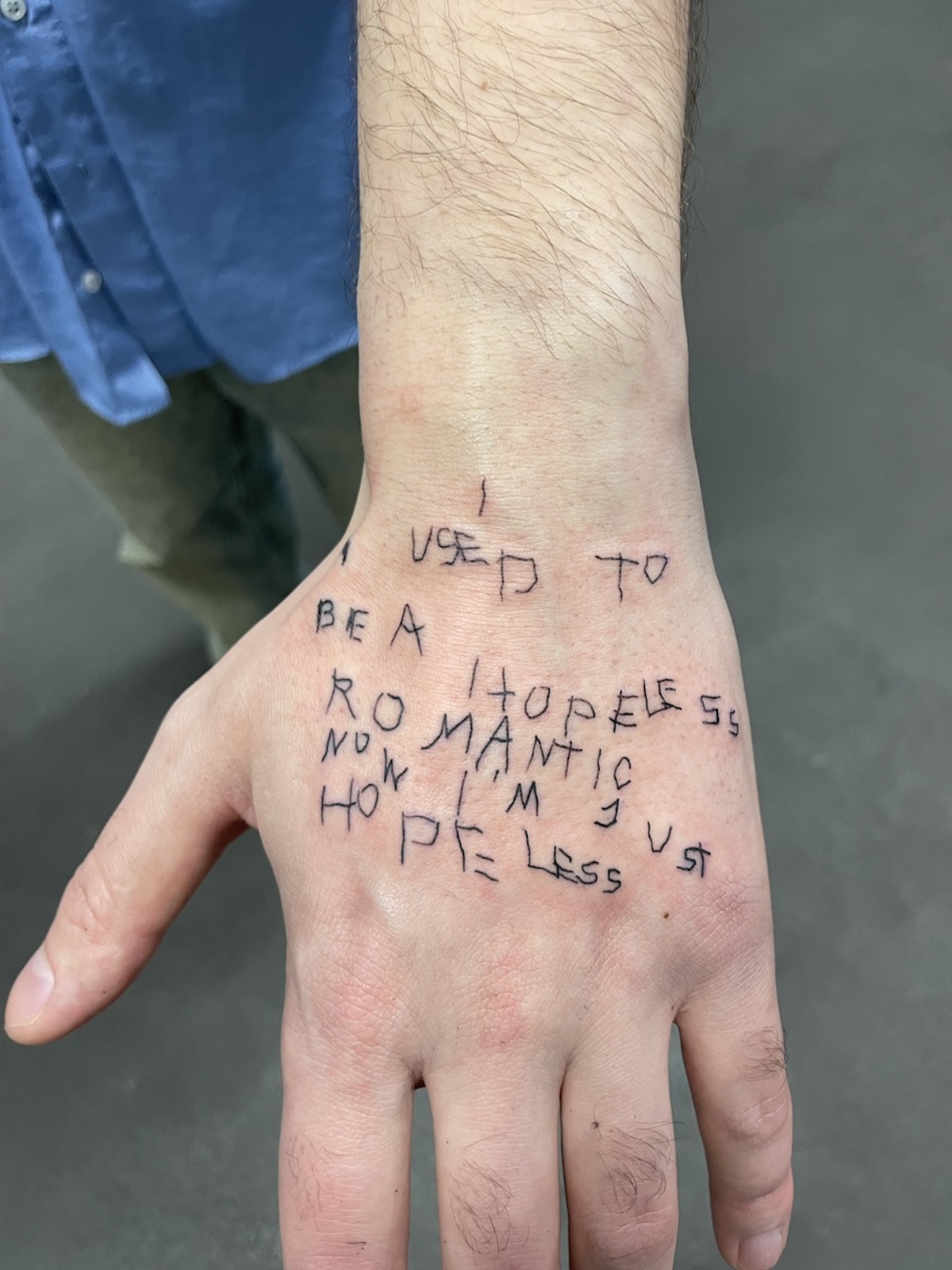

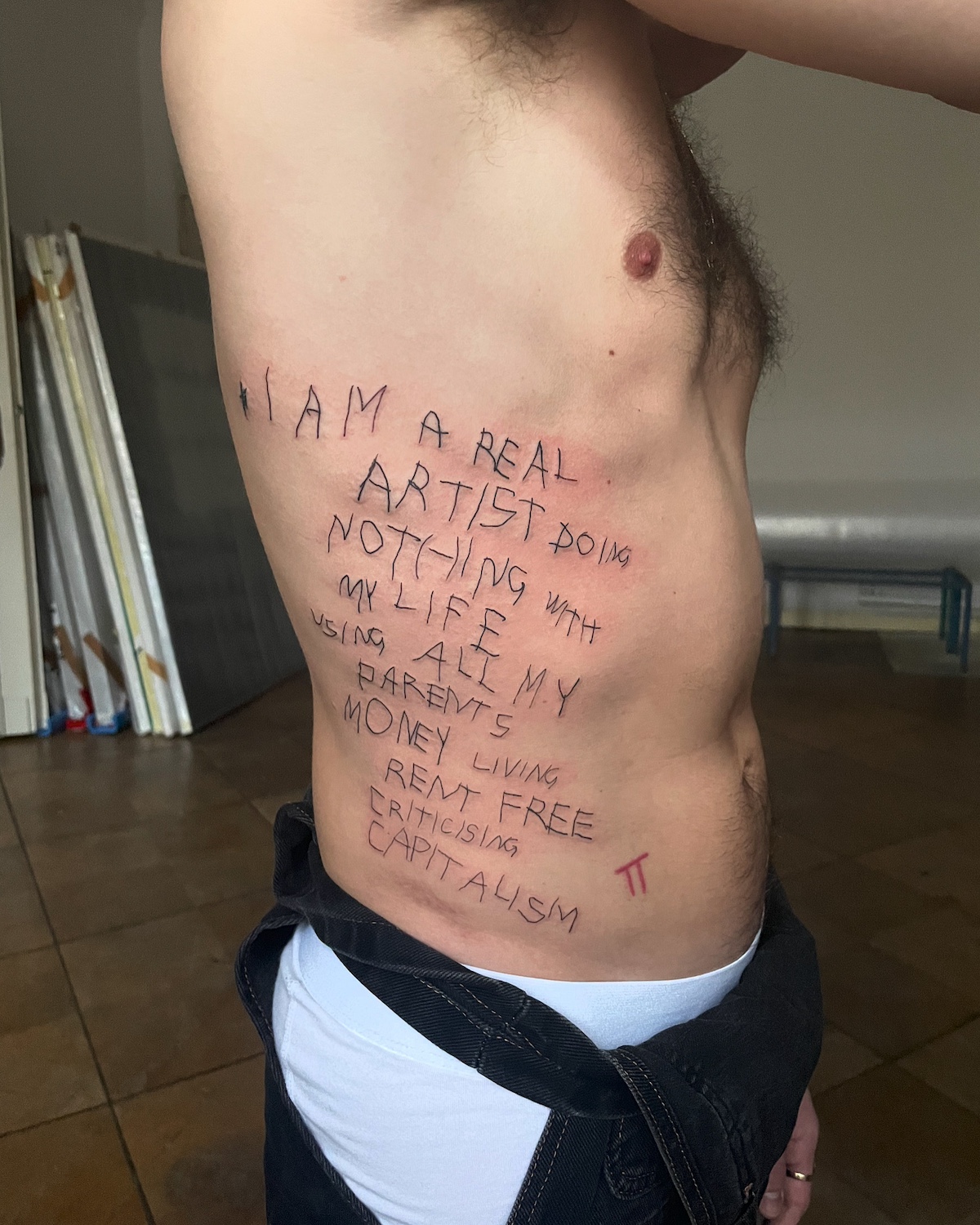

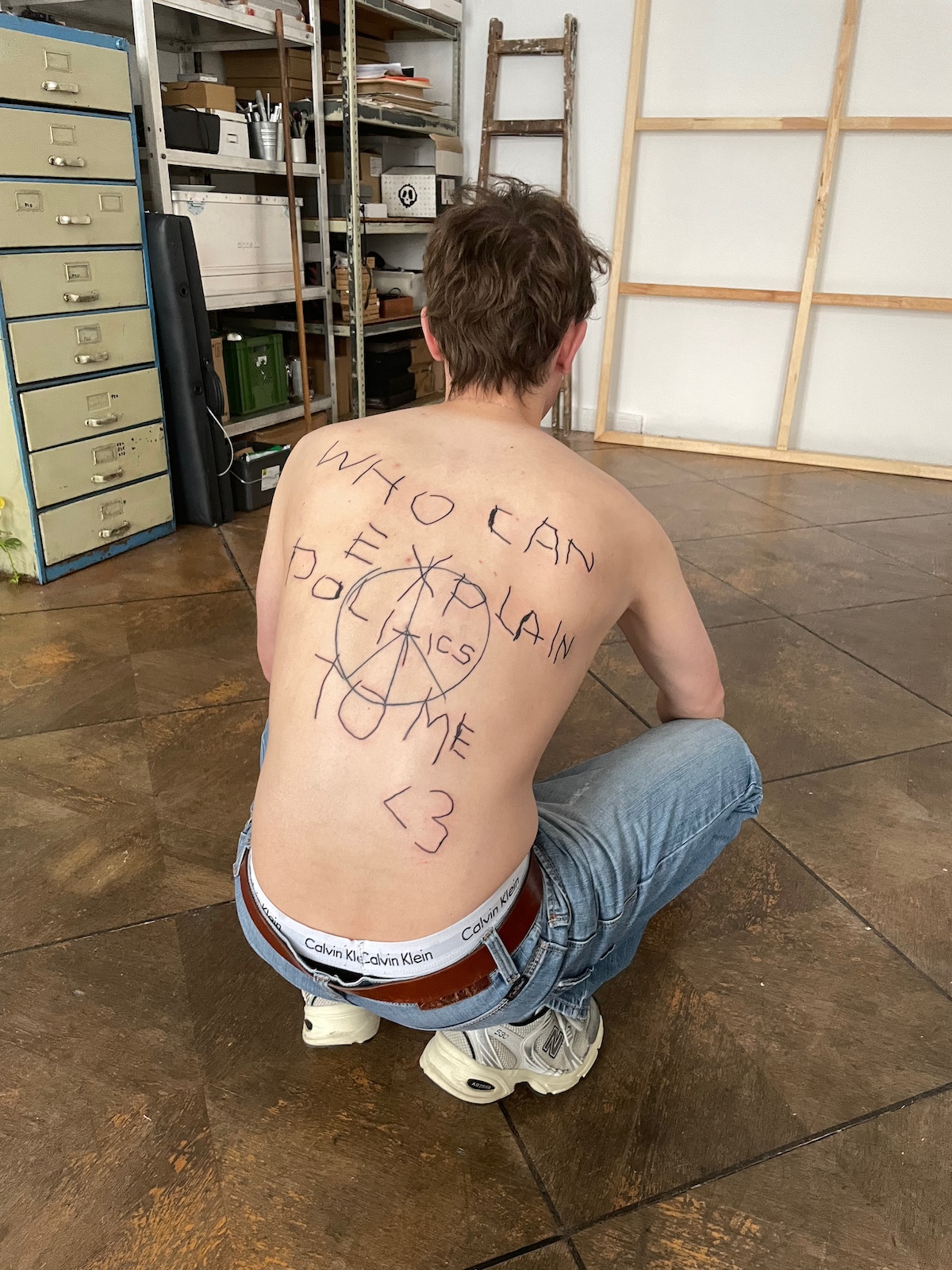

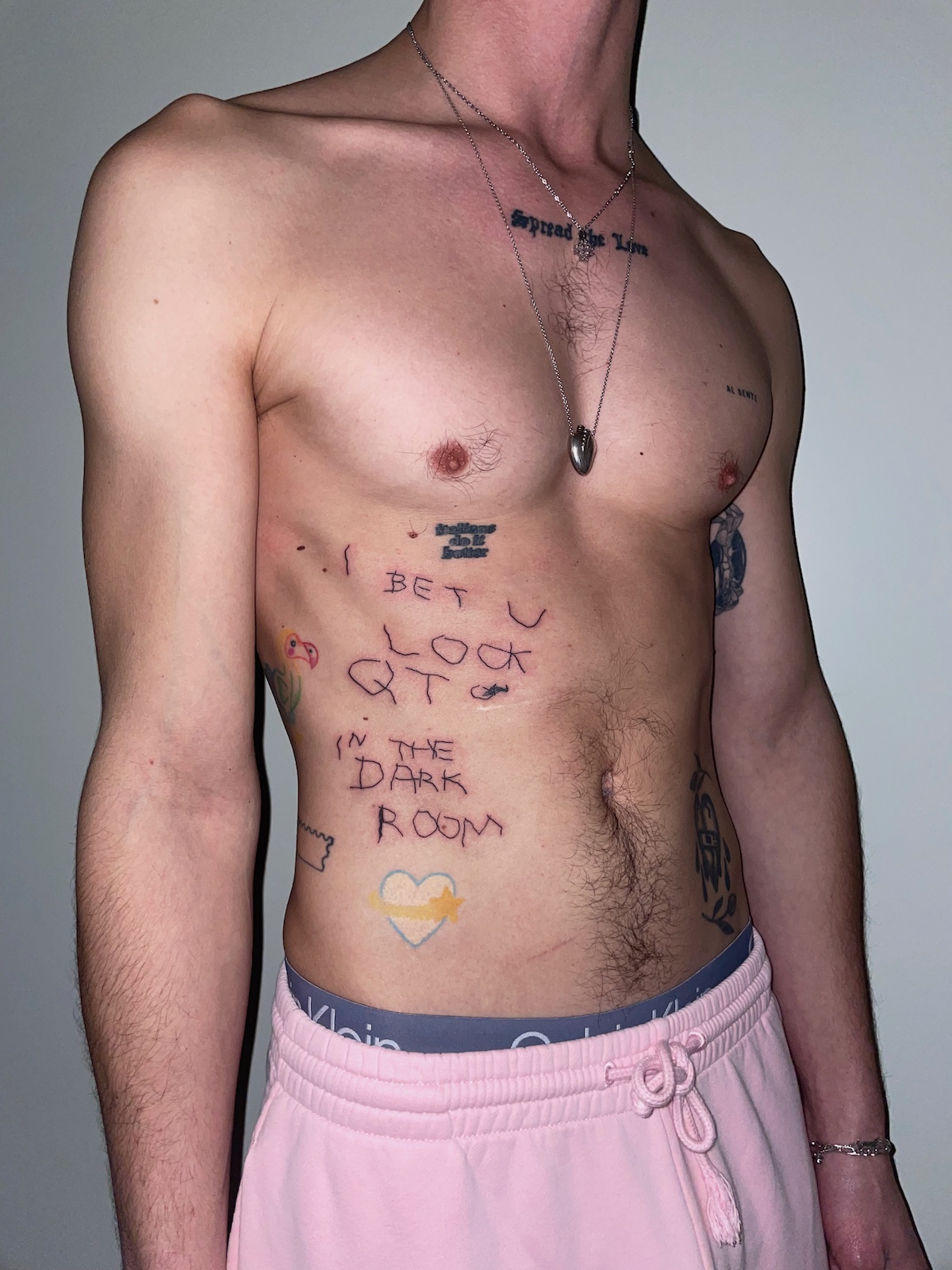

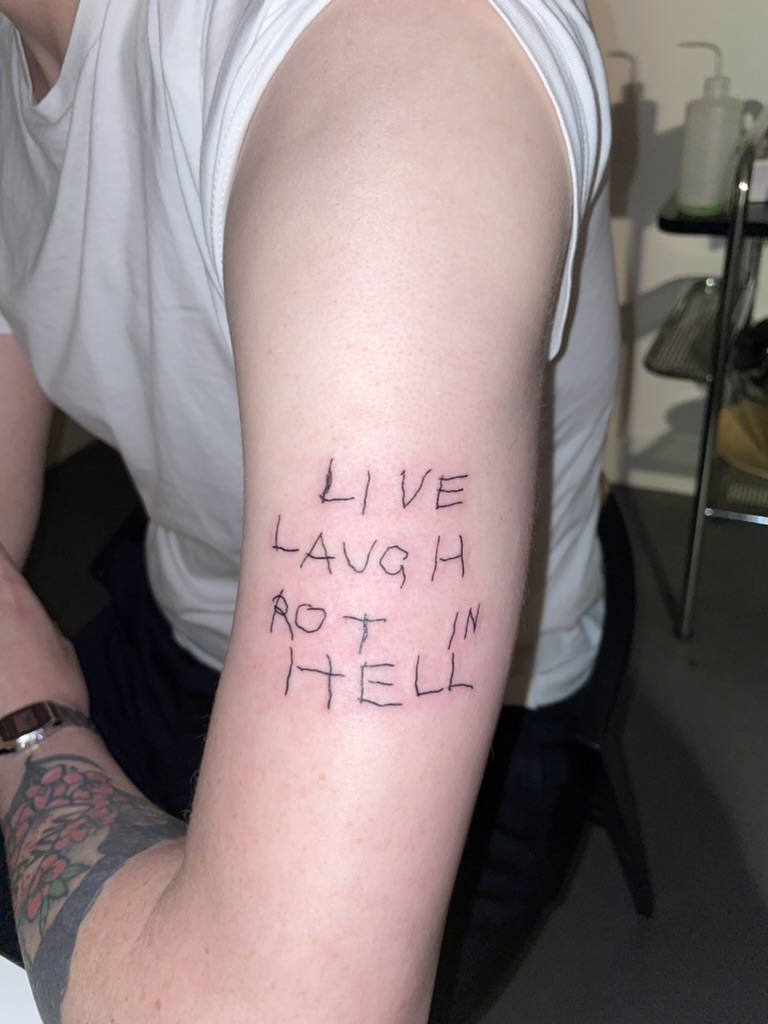

Where do the statements that you’re known for come from?

My texts are like snapshots, similar to photos. They’re memories or notes from certain moments in my life: observations from things that happened to me, things that I thought of, dreams, etc. I basically just write whenever I have time and I write until my head is empty. I have a lot of input and I need to let all of it spill out. It’s how I process things. I take out the trash.

Love that.

And I keep them all in shoe boxes, like time capsules.

That reminds me of when I go home and get to flip through the box my mom keeps all of my stuff from growing up in. I give her a hard time for it sometimes but I’m actually so glad she’s kept it all for me.

It's 100 percent like that. There's no order whatsoever. I can only roughly guess what time things are from based on the style of my handwriting or the content.

It’s interesting seeing how my handwriting has developed over the last decade. I have multiple different styles of handwriting depending on what I’m writing or how I’m feeling.

How important are these statements to your work?

Text is always the foundation of my work, but not always the visible end product. It is the basis for my ideas but from there my thoughts develop. I think of it the same as writing a script. You might start with black words on white paper but it eventually becomes a vivid moving image.

To be honest, because of Maison Hefner, I mostly know you for your tattoos. What has your art journey looked like though outside of that?

Although I went to an art school I didn’t learn to paint until after. I taught myself. And I started doing small shows with my friends, which is how I met my gallerist, André Schlechtriem. He gave me the opportunity to have my first big gallery show at Dittrich & Schlechtriem. I developed the idea for an installation called “If This Is You Who Am I”. It combined poetry and painting with sound and light and was brought to life in collaboration with Yasmina Dexter and Elias Asisi.

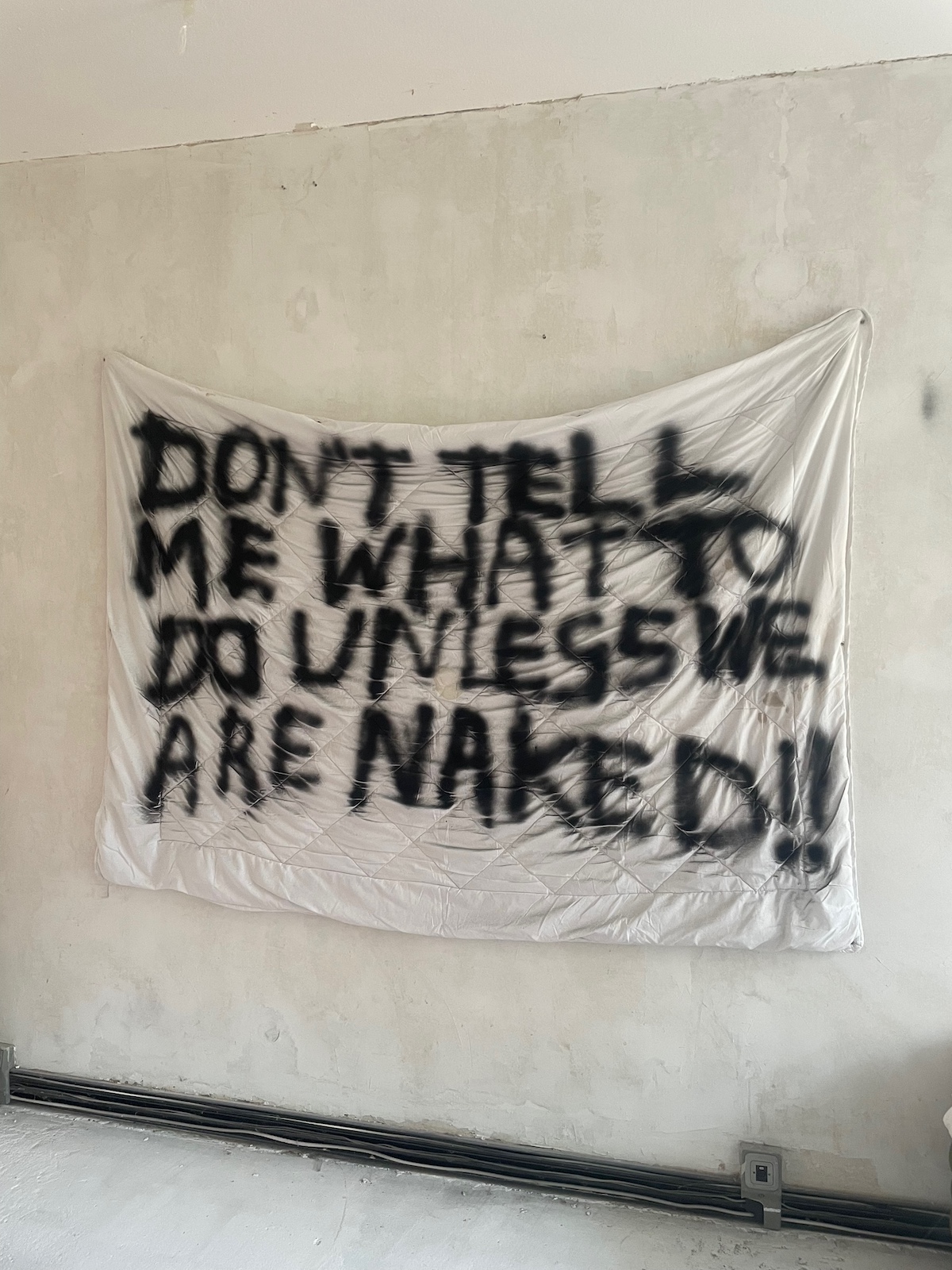

Do you want to talk more about the show you just finished at NAK Neuer Aachener Kunstverein, THANK GOD GOD IS DEAD?

My father died when I was only 18 years old and I felt alone trying to confront my thoughts and questions about it. Writing was a way of processing this grief through a creative channel. It helped me understand myself better as a human — a human that will also die at some point. Sooner or later. I feel like death is a subject people do not necessarily feel comfortable talking about so I wanted to create a space where one can engage with it as part of a collective experience.

The main piece incorporates three coffin-like beds and a sound piece, made again in collaboration with Yasmina Dexter. It repeats a long list of aphorisms: “THANK GOD CAPITALISM IS DEAD,” “THANK GOD SOCIAL MEDIA IS DEAD” and “THANK GOD NOTHING IS DEAD.” The audience is invited to lay in the coffins and I personally found it interesting looking at the people and just wondering what they were going through as they listened.

So are you done doing tattoos… forever?

Maybe not forever. I don’t like the word “forever,” for obvious reasons. But I think for now, I’ve done everything that I wanted to do with tattooing.

Do you have a favorite quote? One that’s not yours.

I have a cap by the artist Jenny Holzer that states, “PROTECT ME FROM WHAT I WANT.” I stole it. It doesn’t always work.

Shot in 1979, the woman in the portrait is identified by nothing other than her first name. Marcus Cuffie discovered this image of Karen alongside a multitude of portraits while they and their sister Morgan were sifting through the extensive personal archive left behind by their late father, Baltimore photographer Steven Cuffie. Save for a few exhibitions in Baltimore before his children were born, the majority of Steven Cuffie’s public facing work was as a photographer for the City of Baltimore, documenting city events, infrastructure damages, crime scenes, and the like. But after his death in 2014, Marcus and Morgan discovered the sheer breadth of his artistic practice, uncovering hundreds of captivating portraits shot in the 1970s and 80s.

In 2022, the pair of siblings worked with the New York Life Gallery to curate the first New York exhibition of their fathers work, in an effort to share their discovery with the world. Now Marcus has partnered with the gallery once again, curating and compiling 26 of Cuffie’s photographs of the eponymous Karen into a zine and exhibiting three of the images and a number of negatives alongside its release. The zine, Karen, is now available for purchase from New York Life Gallery.

Below, Marcus answered some of our questions about the intriguing Karen and their father's archive.

What did your father’s practice mean to you growing up, and if it has changed, how is your relationship to it different now?

Growing up, I knew my dad as a photographer but I didn't exactly think of him as an artist until I was older. The camera was so present in my childhood that it didn't really register to me that the photos he was taking were part of this larger body of work that had been started before I was born. I sort of thought of it like any kid would think of their family taking photos or home videos. He worked for the city as a photographer, so I also knew it was his job, but to me that made it feel more utilitarian than artistic.

That said, my dad was a big supporter of my artistic growth as a child and a big reason I'm able to have focused on being a creative for the majority of my life is because my dad set this standard in his own life. Photo was really all he did since he was younger, and I understood that it made him happy to do that. I think working with the pictures now has given me this kinship with him where I can now see him more as a peer and a point of inspiration. Especially because the work I'm focusing on right now is the work he was making in his late 20's and into his 30's so there's overlap with my own age.

When did you start this process of archiving, curating, and presenting your father’s work to the public? What, if anything, catalyzed it?

The 1st show was in October of 2022 at New York Life gallery, and I started archiving around spring of 2022. My sister had gone down to Baltimore to get some things from our old house around 2018/2019. Christmas of 2019, me and my sister were going through the pictures, a lot of which were images we had never seen before, and I casually posted them on my Instagram and got a lot of feedback from people. Mostly it was people just being positive about the work, I didn't really think at that time that I would do anything with it, and I was doing my own thing in fashion so I didn't really have the time to focus on it. In 2022 my friend Clarke Rudick hit me up about doing a portfolio of my dads work for the 1st issue of his magazine Crosscurrent, and a bit after that Ethan James Green got in touch about showing the work at New York Life as the inaugural show for the gallery. It was really interest from other people that pushed me to make it more of a serious endeavor, I think on my own I felt the images were amazing but I think just getting positive reinforcement from other people made me feel like, ok maybe this can really be a long term project.

What do you know about the subject in the “KAREN” series? Who is/was she?

Really all I have is her name and the dates the photos were taken. I know that she is one of a number of women who reoccur in my dads work in the late 70s but beyond that the relationship she had with him is a mystery to me. Which is the case with a lot of the women in the photos. My dad didn't leave behind much writing about his work, and because this is work that was made in his younger days he didn't really discuss it with us, and in fact these photos were kind of kept out of sight since they can be erotic. I know that some of the women in the photos were definitely women my dad dated, because some images feature him in tandem with the women. Some are just friends or women he asked to sit, though, so there's a range.

Do you consider yourself an artist or photographer in your own right? If so, how does your father’s practice inform your own?

I definitely think of myself as a creative or artist, but I'm not a photographer. I did play around with photo in high school, but I never really stuck with it. I work in fashion as a stylist now and I think my dad and his relationship with photography definitely had a hand in that. I was just as into looking at photo books as he was, and I'm still always looking at and buying new photo books because I have this long relationship with it. I can't say I have like a full technical understand of the medium but I do feel like my taste and my point of view on photo was formed by my dads work, and seeing this work he was making when he was young I do see how without realizing it we have these similar ideas of what makes a good photo. I can't say it's like a hereditary thing but maybe because I was looking at the same things he was, because I had his library of books growing up, it's given me a similar point of view to his.

What do you think makes your father’s work so relevant to this day?

I think what motivated my father is generally what's at the heart of any photographic practice: he was just searching for a way to understand the world, and his camera was a tool for that. I think the photos definitely have certain details to them that age them, but I think when you really look at the subjects in the photos there's a timeless quality to them. In the same way that like Dorothea Lange or Gordon Parks were making images years before my father that he was looking at for inspiration, I think people can look at these pictures now and understand them. Photos break through time because we as people don't really change radically from decade to decade, the details of our surroundings shift but the way in which we relate stays the same.